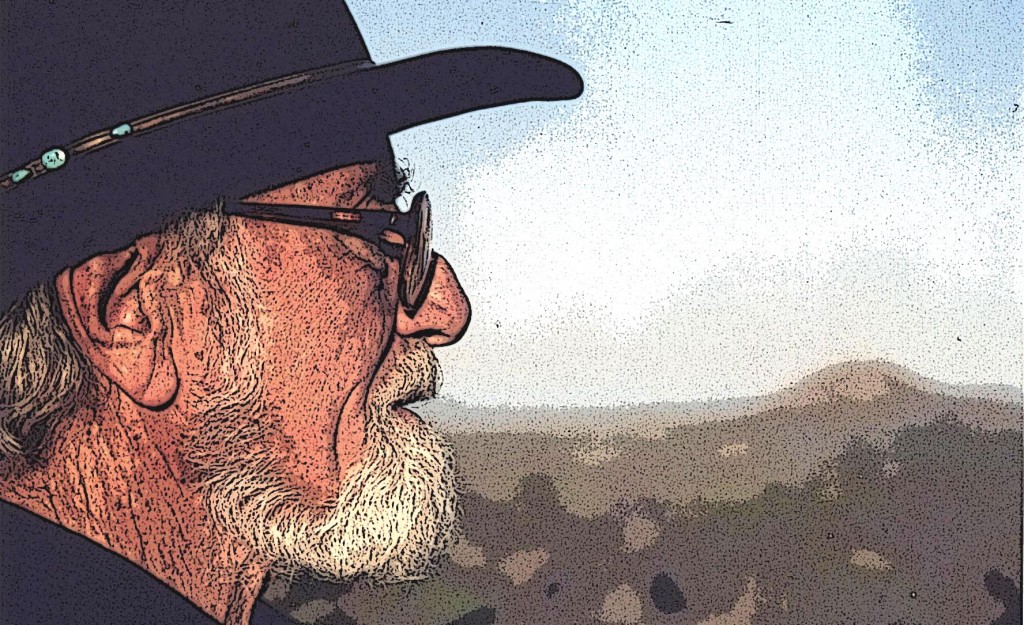

John DePuy: Let me read you something. It says it all. It’s all I have to say. “Madman and seer–– Painter of the Apocalyptic Volcano. Campañero, I am with you forever in the glorious fraternity of the damned.”

Jim Stiles: That’s what Abbey wrote about you…

JD: There’s nothing else to say.

JS: But I have to ask you some questions. Chronology and anecdotes… Where did you come from? How did you get into art? When did you come out West?

JD: Oh God.

JS: What’s wrong John?

JD: Oh nothing, it’s just a very strange question..

JS: Well, John we all want to know where you came from because no one really thinks you came from this planet.

JD: I didn’t. I came from a wolf. It was an immaculate conception.

JS: That’s good to hear.

JD: Well, what screwed us all up was World War II. It formed us. We were formed by the 40s and the 50s.

JS: So you were born in the late 20s?

JD: Yeah, 1927. Don’t remind me. Anyway those were the formative years. Somebody called it the beat generation and we were pretty beat.

JS: How did it affect you personally?

JD: It made me very angry. The whole mess: the Depression, World War II, Korea, which I had a first hand experience with.

JS: What was your experience in Korea?

JD: I was a medic and I tangled with an mine. It was a blessing because it gave me a pension for the rest of my life. I retired at age 22.

JS: You were critically injured, weren’t you?

JD: I have an artificial hip and part of an artificial femur, a lot of metal, but it’s alright. It was a blessing because I could do what I wanted to do which was paint. I always wanted to paint, but this society doesn’t like artists so everything was against me. With the GI bill, I went to the art students league and studied with Hans Hoffman, an old bauhaus type. Hitler hated them and gypsies equally. I grew up with Henry David Thoreau, Emerson, John Muir, Catlin and the land…that was it. The land.

JS: Where did you grow up?

JD: My grandfather’s buried in New Mexico. But unfortunately he lost everything in the Depression, so I was born in the East. God help me. He’s buried nearby and my mom and dad are here near Taos. The 50s are really the formative years, good time. I always related to European paintings, especially the German Expressionists. They were a mad lot and had passion, which some of our art here lacked.

East. God help me. He’s buried nearby and my mom and dad are here near Taos. The 50s are really the formative years, good time. I always related to European paintings, especially the German Expressionists. They were a mad lot and had passion, which some of our art here lacked.

JS: When did you come to Taos?

JD: I came twice. I came when I was very young in the 30s briefly with my grandfather. My parents came back in the late 40s. I came permanently in ’52.

JS: So right after you got out of Korea?

JD: I went out even before that. I took somewhat of a leave of absence and went out to Navajo Mountain and spent some time with an old shaman. I was a navy medic. I went AWOL for a short time after I got back. My mind was burned out. So, I went out and spent some time with an old medicine man at Navajo Mountain. His name was Long Salt. He was what we call a medicine man. He had quite an influence. Stewart Brand, who started the Whole Earth catalogue, spent time with him too. He was an incredible person.

JS: So, when you got to Taos, just what kind of trouble did you cause?

JS: So, when you got to Taos, just what kind of trouble did you cause?

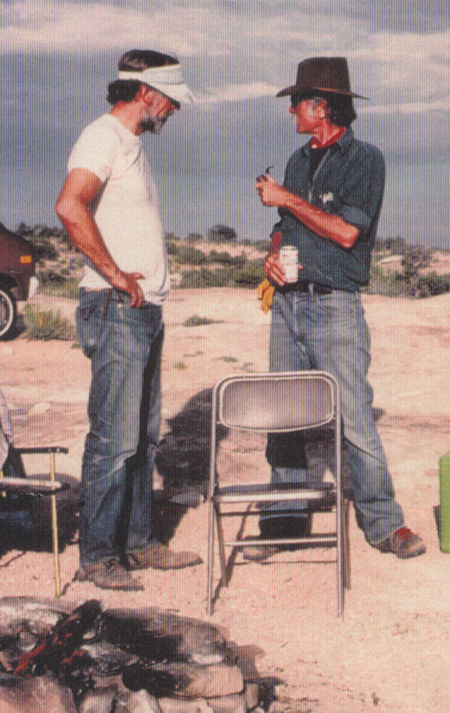

JD: Well, I didn’t really get into serious trouble until Abbey arrived in ’59 and then the shit hit the fan. I had met him before briefly at the university, but then in ’59 we got together with a vengeance. The developers were moving in and that was the origin of what they call the Monkey Wrench Gang. This company in Las Vegas, New Mexico put up six huge signs north of town, big 40,50 foot signs. We decided to remove them and that was the beginning of a long story. But we wanted to save the world. We each pursued our own craft, Ed was a peer. We had a bond that went beyond just friends, we were brothers and we fought like brothers. We went down Thunder River and made an oath to paint and write the Southwest in ’59 or early ’60. He went back to the lookout there…

JS: John you need to speak up…

JD: Yeah, it’s this damn phone. That’s what happens when you drop out, go solar and so forth. Anyway, I stayed in Taos until ’75 and then I went down for a while to join Ed in Tucson. In 1972, I went to Europe to study and England and New York. I had the GI bill so it kept you going; filled the fridge.

JS: Tell us about the time Abbey burned the house down in Taos.

JD: It wasn’t in Taos; it was in Albuquerque. He was a student and a caretaker at a house outside of Albuquerque. I guess they had a party and they left and when they got back the place was burning to the ground. It wasn’t my place, but he wrecked my place in Sante Fe. That was our neighbor’s house. Within two weeks both our wives left us and took all the children.

JS: Do you want to talk about your personal life at all?

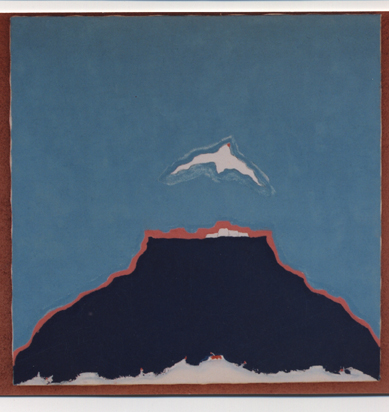

JD: Well, what can I say? I paint. Like Ed said, “All artists should sew their mouths shut.” I started out very involved in the European and New York scene, then I came back to my root right here in the Southwest and the land. The land is my root and my being. Everything I am is the land and I spent 50 years interpreting it in painting and fighting lost causes.

JS: You and Abbey did have tumultuous personal lives. How has that shaped you as a person?

JD: You mean our personal lives with women? It depends. It depends on which woman. Ed and I were both in love with the same woman at one time. She was a revolutionary. She fought at the Bay of Pigs. She and Ed fought it head on; an Anarchist and a Marxist, so she ended up with me. She was an incredible woman. She was la passionaria and a great artist and sculpture, but devoted to the revolution.

JS: So you married her?

JD: Yes, more or less.

JS: That was your first wife?

JD: No. My granddaughter by my first wife is 16 and she is devoted to the canyons; devoted to the Southwest. Good kid; she wants to go to Mars. She wants to be an astronaut. But you know it turns a painting. I grew up in bedroom with Van Goghs all over the walls. It was just something you’re born with. I just couldn’t conceive of doing anything else and I’ve done it with over 4-thousand works here.

JS: Going back the chronology. You had gone to Tucson in 1978.

JD: About that time, I rented a studio from Ed and lived out near Saguaro National Monument. And we hiked and we walked in the Cabeza Prieta. And we spent a lot of time in the Sonoran Desert and back and fourth. We wandered all over the place from the 50s right up to the time he died. He’d sit on a rock and write and I’d sit on a rock and draw. You know Ed’s original love was to be a painter. He was torn between writing and painting.

JS: You were pretty close to him after his wife Judy died.

JS: You were pretty close to him after his wife Judy died.

JD: I was there when she was first diagnosed with cancer. She lived just three months, my God. He really went into a very deep depression and it was rough. He blamed it on the nuclear Nevada tests. We went down to the Grand Canyon for three days and just sat in a cave and cried. My father had just died and we were both feeling pretty rough. Those were tough times. I think if you have life too easy, the work comes too easy. Painting is like writing. There is nothing worse than looking at a blank manuscript or a blank canvas. It’s a nightmare. There was a time when I was up in the Northwest for a period and Ed quit writing for a whole year. He moaned and pissed and complained and groaned. I wrote him a letter saying, “Stop feeling sorry for yourself for Chrissake and get back to work.” He didn’t speak to me for eight months. He was furious, but he got back to work. But we stimulated each other. Those formative years in Taos in the 50s and 60s really formed us with this passion for the West, the Southwest, well the whole West all the way to Alaska.

JS: You and Ed say you formed a pact to write and paint the West; what did you hope to accomplish? What was your own personal goal from that?

JD: Definitive. My goal was absolutely definitive; to do the definitive work of the Southwest in writing and painting and we did it. I feel that I’ve done it. Ed certainly did it. How many can say that they’ve realized their dreams? But it hasn’t been easy. I think you have to be slightly insane.

I remember one time right after our wives left us; his Rita and my Claudine. We went to the bar on Palace Avenue in Sante Fe and drinking our worries away and a friend of ours came in. He sat with us for about two hours and he finally left and said, “I can’t stand being around you two. You’re depressing. You’re hopeless.” That’s how we closed the place at two in the morning, came out of the place, it was midwinter, in the snow and ice singing Schiller’s Ode to Joy at the top of our lungs. We both collapsed in the middle of Canyon Road on the ice. And who comes down the road in two in the goddamn morning, but Rita’s shrink almost ran us over. Then he saw us in the middle of the road laughing our stupid heads off and he stood over us and said, “You are Schwein! You are incapable of being parents.”

I remember one time right after our wives left us; his Rita and my Claudine. We went to the bar on Palace Avenue in Sante Fe and drinking our worries away and a friend of ours came in. He sat with us for about two hours and he finally left and said, “I can’t stand being around you two. You’re depressing. You’re hopeless.” That’s how we closed the place at two in the morning, came out of the place, it was midwinter, in the snow and ice singing Schiller’s Ode to Joy at the top of our lungs. We both collapsed in the middle of Canyon Road on the ice. And who comes down the road in two in the goddamn morning, but Rita’s shrink almost ran us over. Then he saw us in the middle of the road laughing our stupid heads off and he stood over us and said, “You are Schwein! You are incapable of being parents.”

And with that he wrote a letter to both my wife and Rita, Ed’s wife, saying we were both completely hopeless and the result of that was Josh and Aaron went to Rita and my kids all went to Europe.

That was one helluva night. That was a nadir of our lives. But you just keep going. If you can have an intense love for a thing or a landscape, it will sustain you. My work in technique came out of European expressionism, but my love has always been the canyons and it will be that ’til the day I die. I gave Isabelle (John’s wife) the orders to bury me out there.

JS: Are you worried about the future? The future of the landscape.

JD: Oh god, it’s a mess. The hewers and hackers are everywhere and now we’ve got one of the hewers and hackers in the White House. This planet has 30 more years. After that it’s irreversible and swine are really closing in. I’m glad I didn’t ever live to see this time because it’s the worst. It’s not just the canyonlands that are being decimated, it’s the Earth. If they don’t shape up in the next 20 or 30 years, it’s over. The dolphins will take over hopefully. But it has to be turned around. I feel guilty not doing more than I am. But at least there is some hope, the Europeans have turned totally against this stupid government.

White House. This planet has 30 more years. After that it’s irreversible and swine are really closing in. I’m glad I didn’t ever live to see this time because it’s the worst. It’s not just the canyonlands that are being decimated, it’s the Earth. If they don’t shape up in the next 20 or 30 years, it’s over. The dolphins will take over hopefully. But it has to be turned around. I feel guilty not doing more than I am. But at least there is some hope, the Europeans have turned totally against this stupid government.

JS: Well, we have the definitive work from you to remember the West by.

JD: The other aspect, oh I’d better not talk about that.

JS: Go ahead.

JD: Oh shit. The other thing that strangely enough motivates me, which I don’t often discuss; I have a bit of a mystical bent that comes from past experiences way back to childhood. There is so much of this bull going around I hate to even discuss it; all this New Age nonsense. There is a capacity, which the Native Americans know of being at one with the Earth. We’re all part of the Earth and the Earth is part of us. It may seem strange for an old beat like me, but I go out and sit under a tree and meditate every morning before I paint. I just talk to trees and rocks. That’s enough of that.

JS: Do they talk back, John?

JS: Do they talk back, John?

JD: Oh, yeah.

JS: Do they give you answers?

JD: Oh, damn right they do. If I slough off on work, I get kicked. A rock comes up and kicks me in the ass. I’m embarrassed at expressing these things because I despise this New Age nonsense.

JS: As long as you’ve qualified your comments, I think you’ll be okay.

JD: I hope so. But then again…a man at my age, I don’t really give a damn.

To see more of John DePuy’s artwork, visit his website at http://www.galeriedepuy.com/.

To read the PDF version of this article, click here.

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!

As a long-time fan of Abbey’s, what a delightfully insightful look at the man, through the words of one of his closest friends… many times Debris came up in Abbey’s writing. It would seem he is an equal to Abbey for the depth of his life experience and his respectful irreverence for convention.