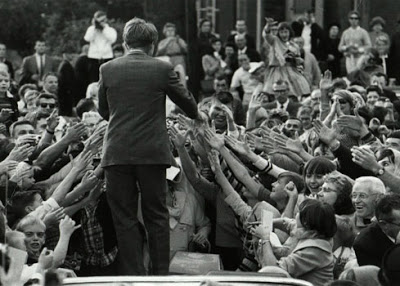

…Excerpts from ‘THE LAST CAMPAIGN: ROBERT KENNEDY & 82 DAYS THAT INSPIRED AMERICA’

By Thurston Clarke

Indiana University Medical School…

He spoke for twenty-one minutes to an audience that a New York Times reporter described as “generally hostile.” There was no applause when he finished and nothing to prevent him from leaving, except that he had not changed a single mind.

…

Another raised the issue of funding again, saying, “All these programs sound very find and nice and all that, but where’s the money gonna come from?”

As at Columbia, Kennedy had finally had enough.

“From you!” he barked, pointing a finger at the student who had asked the question. He pointed at the youth with the Reagan balloon and said, “From you,” then went around the hall, jabbing his finger and shouting, “From you!…You!…You!…You!”

He paused before saying, “Let me just say something about the tenor of that question and some of the other questions. The fact is that there are people who suffer in this country to whom we have some responsibility.”

May 11th.

It would be the last time (George McGovern) would see Kennedy alive, so perhaps that colored his memory of this moment. But others made similar observations during the campaign. NBC took some still photographs of Kennedy during his Indiana whistle-stop. The one he liked best showed him sitting alone in the Pullman car. David Brinkley called it “a terrible poignant picture, just a picture of Bobby, looking sort of lonesome, kind of small…in the middle of that big political entourage.” After traveling with him for weeks in Indiana, John Bartlow Martin observed, “More than most candidates, despite his big staff, he seemed alone. What he did and said was largely his own…He also looked so along, too, standing up by himself on the lid of his convertible—so alone, so vulnerable, so fragile, you feared he might break.” p165

Telling people the opposite of what they want to hear, and making members of a sympathetic audience ashamed of themselves, is a reckless political strategy, but one that Kennedy pursued throughout his campaign. He told an audience of aerospace workers in California, “We should slow down the race to the moon.” When a bellicose student in Oregon demanded that the government mount a military action against North Korea, he told him, “It’s not too late to enlist.” When poor whites in West Virginia complained that they had no jobs and nothing to do, he said, “Well, you could remove those wrecked cars from the side of the road.” During a May 2 luncheon at the Indianapolis Real Estate Board, he was asked if he agreed that the new open housing law discriminated against homeowners attempting to sell their property. Although this was obviously the sentiment of most in the audience, Kennedy’s dissent was blunt and uncompromising. He said: “I think if you are asking people to go fight for us 12,500 miles away…while we are all comfortably sitting in this room—and I am standing here comfortable—and tell them ‘you can die for us but you can’t buy a home’…it seems to me that is rather inequitable, don’t you think?” The Indianapolis Star reported this statement receiving “mild applause.”

While motorcading through Watts on May 29, Kennedy had turned to Richard Goodwin and said, “You know, if anything happens to me, there’ll never be another white politician they’ll trust.” Then, referring to the richness of black culture, he added, “Suppose we do succeed, and the whole country becomes just one big middle class, do you know how much we’ll lose?” (page 260)

May 13. Creighton University. Nebraska.

Speaking over the boos, he said, “What I don’t understand is that you don’t even debate these things among yourselves. You’re the most exclusive minority in the world. Are you going to sit on your duffs and do nothing? Or just carry signs and protest? After scolding them some more, he shouted, “So there!”

A boy stood up and asked, “But isn’t the army one way of getting people out of the ghettos..and solving the ghetto problem?”

Kennedy was stunned. “Here, at a Catholic university, how can you say that we can deal with the problems of the poor by sending them to Vietnam?” he asked. “There is a great moral force in the United States about the wrongs of the Federal Government and all the mistakes Lyndon Johnson has made, and how Congress has failed to pass legislation dealing with civil rights. And yet, when it comes down to yourselves and your own individual lives, then you say students should be draft-deferred.” The Washington Post reported that by the time Kennedy had finished, he had shamed the Creighton students into “a red-faced silence.”

Kennedy became so exercised over the issue of student deferments because they contravened a concept central to his patriotism: equality of sacrifice.

The most unpleasant confrontation of the entire campaign had occurred when Kennedy spoke at the University of San Francisco on April 19. As he walked through the audience to the podium, a student spat in his face and screamed, “Fascist Pig!” (“There was this guy screaming ‘fascist pig’ and spitting at me,” Kennedy told a friend. “And I was looking around to see who he was talking to, and he was talking to me!”)…After he said he opposed student deferments and amnesty for military deserters, a boy bellowed, “You’re a bum, Kennedy!”

The most unpleasant confrontation of the entire campaign had occurred when Kennedy spoke at the University of San Francisco on April 19. As he walked through the audience to the podium, a student spat in his face and screamed, “Fascist Pig!” (“There was this guy screaming ‘fascist pig’ and spitting at me,” Kennedy told a friend. “And I was looking around to see who he was talking to, and he was talking to me!”)…After he said he opposed student deferments and amnesty for military deserters, a boy bellowed, “You’re a bum, Kennedy!”

Asked if he believed in “My country, right or wrong,” he replied, “As Camus said, I love my country, but I love my country in justice the most.”

[Camus had said, “I love my country too much to be a nationalist.”] He gave up and told them, “This happy time—this happening—must come to an end. I was about to say it’s been a pleasure, but I”m glad I didn’t make that mistake.”

Roseburg, Oregon. May 25.

Gun Control opponents also dominated the crowd at the Douglas County Courthouse in downtown Roseburg. Considering his family history, Kennedy remained remarkably calm. He said, “I see signs about guns. I’m wondering if any of you would like to come up and explain.” A burly man identifying himself as the director of the Association to Preserve Our Right to Keep and Bear Arms argued that the bill would lead to a blanket registration of all guns.

“All this legislation does is keep guns from criminals, and the demented and those too young,” Kennedy replied. “With all the violence and murder and killings we’ve had in the United States, I think you will agree that we must keep firearms from people who have no business with guns or rifles.”

Some in the crowd booed. One man shouted that Nazi Germany had started with gun registration. Kennedy continued arguing for the bill. But instead of pointing out that black rioters and militants could easily order guns by mail, an argument that might have appealed to this audience, he defended the legislation as narrowly drawn and guaranteeing that anyone purchasing a gun through the mail was competent to handle it. “So protect your right to keep and bear arms,” he said. “The legislation doesn’t stop you unless you’re a criminal. I don’t think the registration of cars and the registration of drug prescriptions destroyed democracy, and I don’t think the registration of guns will either.” As he left, some of the men carrying signs cheered.

…

The last event that day was a motorcade through Oxnard. As he stood on the backseat of a convertible shaking hands, someone shouted, “That guy has a gun!” An aide ran back to Kennedy’s car, shouting, “Get down! Get down!” An armed man was wrestled to the ground. His weapon was a toy, but Kennedy had not known this, and had refused to duck.

P236

“No one can be certain who will suffer next from some

senseless act of bloodshed.”

April 4, 1968

Robert Kennedy was assassinated on June 4, 1968

Several days after Kennedy’s assassination Charles Quinn of CBS interviewed a group of Southern men who were attending a Wallace for President rally in Memphis. They all appeared to be fierce Wallace supporters, but told Quinn that if Kennedy had lived they would have voted for him instead. They were unable to explain why. “I just liked him,” one said. “I thought he would have made a good president.”

P280

During a “How is Robert F. Kennedy’s Vision Relevant Today” panel discussion, moderator and former speechwriter Jeff Greenfield summarized Kennedy’s political philosophy as “Take your foot off the other guy’s neck!” He recalled that whenever Kennedy told an audience the opposite of what it presumably wanted to hear, “you could almost hear people thinking and changing their minds.” And when Greenfield said this, one could almost hear people in the conference room asking themselves what politician in his right mind would do that now.

p279

In the final year of Ronald Reagan’s presidency, Arthur Schlesinger wrote in an introduction to Robert Kennedy: In His Own Words,”Soon the dam will break, as it broke at the turn of the century, again in the 1930s, again in the 1960s. Sometime around the year 1990, if the rhythm holds, we can expect a breakthrough into a new and generous epoch in American life. When that time comes, the Kennedy ideals will no longer seem so exotic.” That dam has still not burst. Perhaps the mortar of complacency, selfishness, and cynicism holding it together is indestructible. But if it ever does burst, then Robert Kennedy’s ideals, and his campaign, will suddenly seem very relevant

[…] that he wanted to find out more about the call during a campaign stop in 1968, and did in fact travel through Oxnard on May 28, 1968 – just days before his own assassination. Kennedy supposedly […]