Antonio Zapien…

Born:July 23, 1942, Numaran, Mexico

Home: Tucson, Arizona

Profession: Researcher, Animal Husbandry

Antonio tells me such an unusual and poignant story of his journey to America that I ask him to write it in his own words. Throughout this book, other people with a flair with words will write their love letters to America.

MY LOVE LETTER TO AMERICA

For some people, number thirteen is a bad luck number. Not for me. At that age, I met an American couple who changed my life forever.

I was born in a Mexican rural town, the second son of a young campesino couple; my sister died a few months after being born. My mother was seventeen years old when I was born.

My father was a migrant agricultural worker, every year coming to the US, looking for work, and after a few months, with some savings, going back home. I remember walking with him to the outside of the small town, waiting for a bus to come. He left, going again to the US. That was the last time I saw him. I was almost six years old.

The situation for my mother and me was not unique. Her father and several of my uncles also were seasonal migrant workers, so back home many families were made up of women and children, helping each other, surviving. At some point, some men, but mostly women, began moving to the big city, Mexico City, looking for work. My mother was one of them. She followed some family members, and I stayed in the country with my grandmother, several aunts, and cousins. Food was scarce, but we shared whatever we got. I began helping every day during church service, and from the nuns, I got some food. They got busy teaching me to read and write. At some point, my mother came home and took me with her to Mexico City.

She was cooking for a middle-class family, and as part of her work compensation, she had a bedroom and a bathroom at the back of the house. She had negotiated for me to be able to stay with her. She had to find some other family to work for once in a while, so we kept moving; no way for me to attend school. But often, during the afternoons, some families allowed me to be present when their own children were doing homework. The rest of the time, I was free to roam downtown Mexico City.

At some point, a family friend talked my mom into taking me to the Internado Nacional Infantil (INI), a huge place for young male children, twelve hundred of them, different ages, some of them street children, many of them orphans, and some others like me, not quite street children and not orphans. I got accepted, took a placement test, and it was decided that I would be able to start third grade. I was twelve years old, and for the first time in my life, I had three meals a day, my own bed, clothes, and uniform. I was able to attend school every single day. It was early 1954.

One year later, I met Susan (Sus) and Hugh Hardyman. The director of the INI and a social worker representing the Hardymans came to our classroom to announce that an American couple was looking for six young children who wanted live with them in a farm outside Guadalajara. As several others, I raised my hand. They took our names and gave us permission to go home and bring back our father or mother, to have a special meeting and go through a legal paperwork process. With my mother’s permission, I became part of the group of six boys. The following day, together with a couple of teachers and a husband and wife hired by the Hardymans, we boarded a bus that took us to meet them and the place that became my new family and home. That was my first contact with American people and the beginning of a never-ending learning process.

Life with Sus and Hugh was like a big family. The house was, and still is, a big, very old beautiful hacienda. We learned that, yes, the farm had chickens, rabbits, cows, fruit trees, and more. The first few days, we did everything together, adults and young people, on the farm, in the dorms, the bathrooms, kitchen, and dining room. We began learning how to use and take care of everything.

It was a hands-on teaching and learning process. Meal times or other collective meetings were used as a way of communicating about everything. I had to pay really good attention because both Sus and Hugh were not exactly bilingual, and I was just getting familiar with American people and the sound of English. They tried to communicate in Spanish with us, especially Sus. In English or Spanish, Hugh was a very calm, soft, direct speaker.

We became busy with school work in a very intensive way. I was thirteen and considered too old to be in fourth grade. I began paying attention. Somehow I knew it was true when they told me, “Try your best, always. We are here to help you.” We watched and participated with them in the life of the village and got involved in several projects, like advocating at the state level for a new elementary school, medical services, introduction of electricity, and building a road to connect the village to the main highway.

By watching them, I became familiar with books. They were always reading, especially in the afternoon and late at night. Suddenly I noticed books everywhere, in English and Spanish, and began reading all kinds of books in Spanish. I asked the Hardymans about the content and topics of the ones in English. Step by step, I began reading some books in English.

We began getting visitors, many of Sus and Hugh’s old friends from the US, and new Mexican friends: writers, musicians, painters, carpenters, and many social activists. I learned about social and political issues in the US and Mexico–segregation, racism, poverty, inequalities, and human rights.

At some point, it was time to go somewhere else to continue my education. I got a scholarship to attend a junior high school, with the idea of becoming an agricultural engineer. With Sus, during the summer, I began visiting the US and got to know some of her old friends. During my high school years, some young American students came to start a kindergarten in the village. As a result, I met my future wife. Two or three years later, during my university years, we got married.

With the support of the Hardymans, I, and many others, went to the University of Guadalajara. I became a veterinarian, doing research on cattle production. After graduation, the three of us–I, my wife, and our son, who was born one year before my university graduation–moved to the tropical region of Mexico to start my professional life.

Over the next thirty-five years, from 1971 to 2006, we were in and out of Mexico. We came to the US, first to get my Master’s degree, and few years after that, a PhD. In between, we came to visit Sus Hardyman and my wife’s family. Our daughter was born in the US during my Master’s program. During my Doctoral program, I applied for and became a US resident. Now I’m a US citizen and, like our two children, have dual citizenship.

Looking back, I find it difficult to say how fortunate I was to become a foster son of that American couple, Susan and Hugh Hardyman. Because of them and their friends, the family they created for me with many brothers and sisters, along with my wife and my wife’s family, I had the chance to get to know the very good side of the US. At the same time, I became a critical thinker, recognizing America’s problems. Their support, guidance, and protection gave me the opportunity to become a useful citizen of both the United States and Mexico, and in the process to build my own family, a true binational, bicultural family.

I journey to Tucson to talk more with Antonio. We sit at his dining room table in a modest home filled with Mexican art and comfortable furniture. Large rear windows reveal a patio and garden filled with colorful tropical plants.

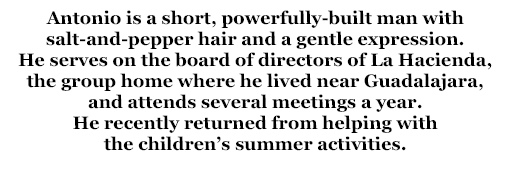

Antonio is a short, powerfully-built man with salt-and-pepper hair and a gentle expression. He serves on the board of directors of La Hacienda, the group home where he lived near Guadalajara, and attends several meetings a year. He recently returned from helping with the children’s summer activities. “They have twenty-nine kids from second grade to university level,” he tells me proudly. “The Hardymans have died, but another family is keeping the house going.”

In 2006 he sold his house in Hermosillo and moved permanently to Tucson. Now he serves as adjunct professor at the University of Arizona and helps old friends, graduate students, and professors. His wife, Jill, is associate dean of the university’s College of Public Health. “Jill really held the family together throughout our life,” he says with admiration.

He ticks off his current activities with precision.

“I volunteer at the university.

“I’m designated driver for my two grandchildren, Camilla, who’s six and-a-half, and Benito, three and-a-half. They’re Rebecca’s children and live in Tucson. In the summer, I take them to day care and summer camp. The rest of the year, three or four days a week, I pick Camilla up from school and Benito from day care. We all try to get together every week for dinner here or at a restaurant.

“Jill and I have talked,” he continues, “and I’ve said I don’t think I spent much time with my kids when I worked in Mexico. Jill says, ‘Yes, you did, but not as good as now!’” He laughs ruefully. “We never talked about this with the kids; they just accepted my schedule. But they didn’t like it when we were moving between Mexico and Tucson because they were losing friends. Three or four times a year and every other Christmas, we travel to see our son, Ivan, who lives in Washington, DC, with his American wife, Vicky, and their two children. On alternate years, they go to Vicky’s parents.

“My last job,” says Antonio, “is working with the migration groups Samaritans and No More Deaths.” He’s staked a small sign reading “No More Deaths” in his front yard.

“Once or twice a week, I go to the No More Deaths aid stations on the Mexican side of the border. When migrants are deported every day from the US, they come through, and we provide first aid, food, clothes, communication, whatever they need. We get about a hundred people a day. Five, six years ago, we got one thousand to two thousand a day.”

Antonio also tries to find belongings that people have lost after being arrested by the border patrol. “These migrants go to jail, and many times, their backpacks and personal belongings, like identification, money, and pictures, are taken or get lost,” he explains. “We get that information, and I go to the Mexican Consulate in Tucson or the immigration lawyers. They help us move through the system, get to the border patrol, and return those missing belongings to the owner at the Mexican side.”

I ask, “Do you see the same people going back and forth?”

“No, not very often,” he replies.

His work with Samaritans involves driving into the desert one day a week. “We leave early morning from Tucson and head west–two, three, four of us in one car,” he tells me. “We know some places that migrants are walking, going north, so we park close by and hike all around, looking for them. We carry food, water, clothes, and first aid.

“When we see them, we give them help, and talk with them. Some are OK, but if one has a medical emergency, we call 911 and ask for help. We stay with the migrants until the officials arrive.” Generally, he says, the officials and Samaritans give each other wide berth.

“The one thing we don’t do is transport any migrant,” he says decisively.

I ask, “After thirty-five years of going back and forth across the border, being a privileged traveler, how did you come to realize the plight of illegal migrants?”

He answers slowly. “I never thought about migration the way I see it now until I came to Tucson this last time. Then I began paying attention to that. In Mexico, in my job, I saw the internal migration within Central America, thousands of people coming to northern Mexico, to work in agriculture in different seasons. I saw them, but I never thought about the conditions that forced them to come.

“When I came to Tucson in 2006, suddenly I made the connection. I’d lost my father, and my father was one of them, a migrant worker. Now when I saw so many people coming illegally into the US, I saw the same faces as those I’d seen in northern Mexico. And I saw the face of my father.” He smiles gently. “I felt a mix of anger and frustration, thinking about how it’s possible that millions of people are going through that process, and it’s been happening all my life–forty, fifty, sixty years, the same thing, people coming but not changing the way of life for them.”

He continues quietly. “I got angry with the Mexican government and the political system because they can’t make the country economically viable for their people. The US government has a lot to do with that because it makes Mexico so dependent on it. The US government has allowed people in the US and Mexico to get rich. I believe the two countries must work together now. Otherwise Mexico can’t solve the problem. The American companies that set up factories in northern Mexico pay really low wages, and the workers don’t get enough money to live. It causes a lot of social problems.” He frowns.

“Many people confuse us Samaritans with those people who give help just to feel good,” he says emphatically. “We do it because people all over the world have a right to migrate, to eat, to have a place to live. It’s a basic human right. When you don’t think about the human rights, you have some limitations. Humanitarian aid is never a crime.”

I ask, “Do you feel Mexican or American?”

Quickly he answers, “I feel Mexican. It’s my culture. I don’t feel American. I got dual American-Mexican citizenship in 2006. I waited a long time, and I did it only because it made it easier for us as a family to do all the legal things: taxes and paperwork. My children are bilingual and bicultural. My wife speaks and writes Spanish better than I do. When we’re together, we speak more Spanish than English. It’s the same with my daughter.”

Antonio also speaks Spanish to his grandchildren. Their parents don’t mind. “They just don’t want me to require the grandchildren to speak back in Spanish,” he explains, with a smile.

“Seven-year-old Pilar, who lives in Washington, DC, is bilingual. Her brother, Marco Antonio, is getting to be bilingual. Their parents are very much into learning, and they speak some Spanish at home. Pilar had a Bolivian nanny who taught her Spanish. A new nanny is teaching Marco. She’s the driving force for speaking Spanish in that household.”

In Tucson, Antonio keeps the Spanish going. He talks to Camilla and Benito in Spanish. “They’re learning,” he says brightly “We’re teaching them Spanish, but without a lot of effort. Their mother, Rebecca, is OK with this, and so is her husband, Duncan, who’s African-American.

“Our family is binational, and we like that,” he says resolutely. “We don’t have to choose. We share both cultures.” He opens both hands expansively and beams.

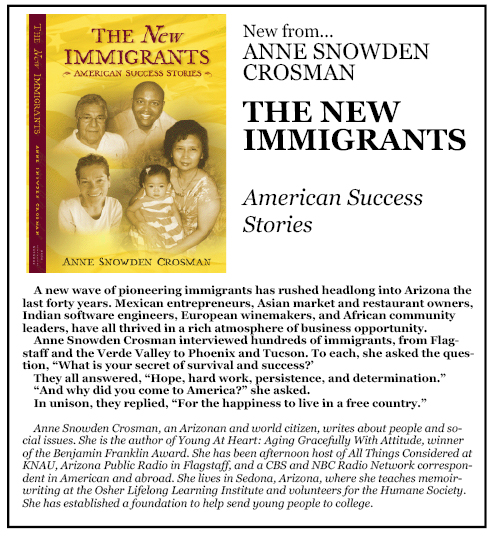

Anne Crosman is an author and free lance journalist in Sedona, AZ. She teaches memoir writing and edits books.

Her earlier book Young At Heart: Aging Gracefully With Attitude (2003, 2004, 2005) won a national Benjamin Franklin Award and a Washington Irving Book Award in Westchester County, NY.

She has been afternoon host for “All Things Considered” on KNAU, Arizona Public Radio, Flagstaff, AZ.

She was a CBS and NBC Radio Network News Correspondent in NY, Washington, and Geneva, Switzerland. She freelanced for The Christian Science Monitor, The Washington Post, and Newsweek.

She is working on a new book about organ-transplant recipients and welcomes ideas from any CCZ readers.

Anne has been a member of the Sierra Club since 1955, when her parents took her down the Green River on a SC trip.

Her new book, “The New Immigrants,” is available on Amazon.

To read the PDF version of this article, click here.

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!

![]()