Millions of years ago, according to one theory (mine), the mammoth child of some now extinct race of giants spilled globs of wet sandstone clay, red as rusted iron, on the Nevada desert in what is now known as the Valley of Fire. Perhaps she was modeling some kind of prehistoric jack-o-lanterns, for she poked holes in them with her fingers so the mounds were riddled with grotesque eyes and noses and mouths. Whatever her intention, she left them to dry and forgot to come back.

Some of the globs are a hundred feet high, some only ten or fifteen. As I arrive, looking for a place to camp, the late afternoon sun is turning them red as fire and the holes––enlarged and sculpted now by eons of wind-blown sand––hold shadows so black that I know without going too close that some blood-thirsty, bone-crunching horror lurks in the holes, just waiting to pull me in. I decide that this is just the right place, for even though I am now a jaded old iconoclast who in her old age has taken to wandering around in the desert alone, I have never lost my childhood delight in using my imagination to terrify myself.

It’s not long until sunset, so I lay my sleeping bag out on a flat, clean, sandy place. Then, with my notebook and canteen, I climb to the top of one of the sandstone mounds (carefully avoiding the black holes) to watch the sun go down and write in my journal.

The bee comes at first in wide circles. Initially I give him no more than an uneasy suspicious glance, but the circles get smaller and smaller until he is very close and I get nervous. “Buzz off,” I tell him, and when he doesn’t obey, I abandon the mound, grumbling.

I walk up a natural pathway through the mounds, looking for another space to claim. But the bee comes with me. He dashes ahead, swoops and turns, zooms past me, dashes off to the rear, banks and turns, buzzes me again. I see a stick lying on the ground, a slender switch. I pick it up and whip it in his direction. It only makes him mad. He dives at me like a fighter plane strafing a battleship.

“If you get too close I’m gonna shoot you down.” I’m bluffing of course. I know I can’t hit him. He answers by zooming so close to one ear I can feel the draft from his wings.

We go along this way for a while and I’m getting more and more irritable, thinking that if he doesn’t quit I will have to get in my car and find another place to camp. Not a pleasant prospect this late in the day, as it will soon be dark. But then I come to a large hole in a mound––a gaping mouth, actually––and after peeking in to make sure there are no loathsome beasts lurking there, I duck in. Inside, I can almost stand up. It has the fresh, clean clay smell of cool sandstone, nothing but fine red dust on the floor, and it feels like it’s ten or fifteen degrees cooler than the desert outside. The gaping sandstone mouth horror has turned out to be a haven. The bee has not followed me inside, though I can hear him buzzing around outside. I sit down and drink from my canteen and decide I will wait here for the bee to leave.

More of a cubbyhole than a cave, my little refuge arouses pleasant memories of hiding places I treasured as a child: a nook behind the hay in the barn on my grandfather’s farm; a tunnel through the roots of the giant pampas grass that grows in Florida, where I grew up; a tiny closet under the stairwell, where I hid when my feelings were hurt. I remember the smell of the hay, which made my sinuses run, and the pungent odor of the pampas grass when it rained. But here, there’s only the light fresh smell of sandstone, barely noticeable. I drag my fingers through the clean sand on the floor of my alcove, making little troughs. What a place to sleep if it rains, I think.

About that time I hear the bee again. He is reconnoitering the entrance to my cave. “Get away from here. This town ain’t big enough for the two of us,” I yell. You have to understand that I have been alone on the desert for a week and I am talking freely to anything and everything. It doesn’t matter how silly you get if there is no one to hear you but a bee.

The bee starts in the entrance and I lash at him with the stick. Although I’m in a totally defensive position, I have the advantage. He can only come one way and I’m ready for him. He tries it over and over again but I fence him off every time, even doing some fancy Zorro-like sword work, enjoying the battle now that I am in a somewhat secure position. I wonder what the attraction is, why he is dogging me as relentlessly as Captain Hook’s crocodile, but at any rate I know he will have to go home when it starts getting dark, and the sun is already gone.

Sure enough, when the light starts to fade he leaves. I crawl out and return to my sleeping bag. I go to sleep marveling at the stars, a hundred times brighter in the dark night of the desert than they are in the city, a thrill that never gets old.

That night there is a windstorm and I tunnel all the way down in my sleeping bag even though it is hot. It’s my first desert sand storm, and once in a while I put my face out with my eyes squinted shut just to feel the sting of the wind-whipped sand on my face. I imagine myself in the Sahara desert, separated from my unit of the French Foreign Legion, which has made an exception to the all-male rule in my case and allowed me to join due to my demonstrated courage in the battle of Quong Zai. I only have to survive until morning, when search planes may yet find me if I am not suffocated during the night by the blowing sand, or maybe they won’t find me and I will die of dehydration before the day is over. Once again I have managed to thoroughly terrify myself and the bee is completely forgotten.

In the morning my hair is thick with sand. It feels like crumpled plaster and I can’t comb it. My mouth feels like someone emptied ashtrays into it. I remember I saw a campground not far from where I slept and I go there to look for water. There are no people and it looks abandoned, a ghost campground. Probably just too hot this time of year.

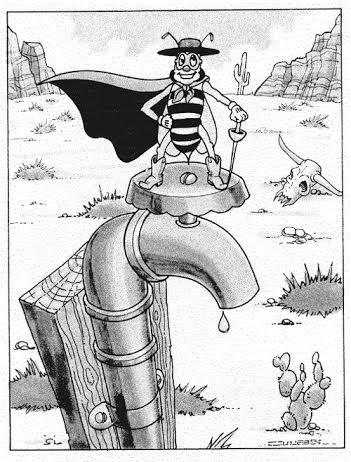

I walk around until I see what appears to be a solid post of bees planted in the ground, standing perhaps two feet high. It’s an astonishing sight and I get as close as I dare, thinking I am witnessing a strange swarming phenomenon. Rather late, it occurs to me to wonder if they might be killer bees, but then I think, No, if they were I’d already be dead meat. The bees move constantly, an undulating stamen of yellow and black, and then under their pulsating bodies I see little spaces of something gray and metallic. I approach a little closer, and realize that what I am looking at is a pipe sticking up out of the ground, with a faucet at the top. My water, turned into a fountain of bees.

I sit on the ground to reason the situation out but I can’t think of any way to turn the faucet on without disturbing the bees, and they are sure to be mad at me. I can deal with anybody being mad at me but a bee. A hundred bees in bad temper I can’t even bear to think about, even if they aren’t killer bees. I begin to reason with them. “Look, I know you consider me a natural enemy, but you need water and I need water. It’s that classic dramatic situation where enemies must cooperate if they are to survive. You’ll recognize that immediately if you read much fiction. You can’t turn the faucet on and I can. Now here is what I’m gonna do. I’m gonna reach in there and turn that faucet and we’ll all have water and you’ll go your way and I’ll go mine, okay?”

I reach for one of the bare spots on the faucet and push with the tip of my finger. A trickle comes from the pipe and the bees explode, every living one of them, two feet in the air with a sudden mighty ZZZZZ, then they dive for the water on the ground. It all happens in a second and then it is quiet, a solid blanket of bees on the ground, drinking.

As I put my canteen out to fill, I remember the bee of yesterday and realize what the attraction was: he’d wanted water; he was after my canteen. Well, why didn’t he just say so? I ask irritably. Maybe he did, I answer, maybe you just weren’t listening.

I fix the faucet so the water keeps coming a drop at a time, and will keep on coming until another human comes along and turns it off. While I’m doing this I do a rerun of yesterday’s incident, and in the rerun I have it come out that I paid attention to the bee. I analyze his behavior calmly and intelligently and figure out that he is not playing Zorro with me — he must want something I have and that something can only be water. Then I have me sit down and take the cap off the canteen and pour a little water in it, more than he can ever drink, and the bee sits on the edge of the cap and drinks up as much as he can and then flies away home, with me sitting there making friendly chit-chat until he leaves.

The rerun doesn’t make me feel any better because of course that isn’t how it was––it never is between humans and wild creatures. I was over-Disneyed in my youth and the corruption has persisted even into my old age. I make up my mind: no more fantasy, no more cutesy dialog with the wild things. It keeps me from knowing what’s really happening. Meantime, the best I can hope for is that the bee of yesterday was among the bees at the faucet this morning.

Toni McConnel lives in a tiny village in the high-altitude forests of Northern Arizona, where she fled from the ravages of tourism on her heart’s home, Moab, Utah. She is the author of a novel based on her experiences as a prisoner, Sing Soft, Sing Loud (http://www.singsoftsingloud.

To read the PDF version of this article, click here.

To comment on this article, scroll to the bottom of the page.

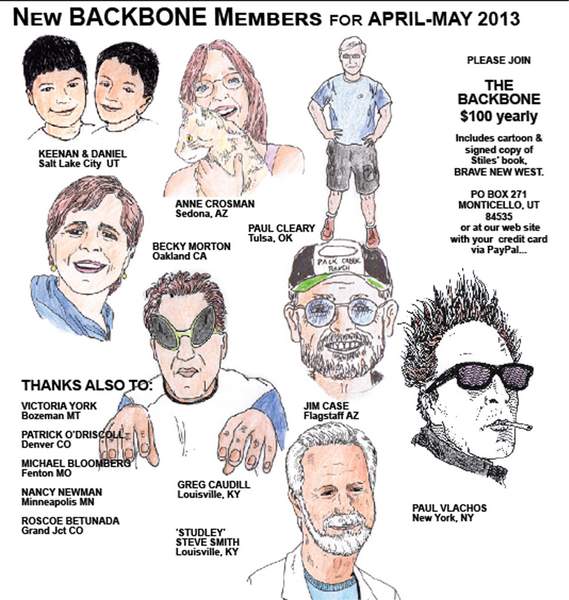

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!