How does a small, scrappy desert conservation organization, unheard of by most westerners, funded mainly by membership dues and run by volunteers for most of its 60 years, continue to make its voice heard on proposals for large energy development projects and other misguided ideas for exploitation of irreplaceable natural and cultural resources for private profit on our public lands in the Mojave and Sonoran Deserts.

The Desert Protective Council (DPC) continues to be the longest-lived desert conservation organization in the U.S. for a combination of reasons. First, DPC’s educational mission and goal to protect the unique features of the deserts are still extremely relevant. Also, DPC’s founders were some of the most respected biologists, educators and conservationists of the day. Perhaps too, the DPC continues to play a role in desert conservation due to the loyalty and support of its long-term members and advisory panel members and because, despite its small size, DPC has for decades consistently “shown up” and participated in important desert land use planning processes and continues to speak out, without compromise, against damaging development proposals such as the rash of current desert-wide large-scale solar and wind development proposals.

The Desert Protective Council (DPC) continues to be the longest-lived desert conservation organization in the U.S. for a combination of reasons. First, DPC’s educational mission and goal to protect the unique features of the deserts are still extremely relevant. Also, DPC’s founders were some of the most respected biologists, educators and conservationists of the day. Perhaps too, the DPC continues to play a role in desert conservation due to the loyalty and support of its long-term members and advisory panel members and because, despite its small size, DPC has for decades consistently “shown up” and participated in important desert land use planning processes and continues to speak out, without compromise, against damaging development proposals such as the rash of current desert-wide large-scale solar and wind development proposals.

Beginnings

The Desert Protective Council was established on October 23 1954 around a campfire in Deep Canyon at the base of the Santa Rosa Mountains in the Coachella Valley of southern California.

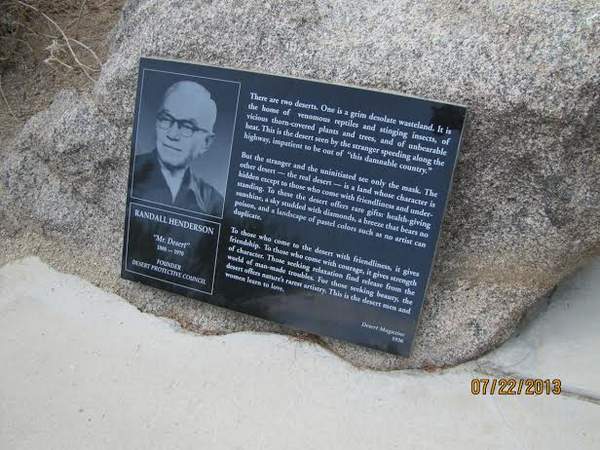

The DPC’s conception was a bit earlier than that. Former DPC President Harry C. James started an outdoor organization for boys in 1913-14, called the Trailfinders. Several times per year, Trailfinders sponsored a Conservation Forum to which many adult Trailfinders alumni and representatives of other outdoor organizations came to talk about “the many matters connected with preservation of our outdoor heritage.” It was at one of these meetings in the early 1950s that attendees suggested the need for a conservation group whose primary interest would be the desert regions of the Southwest. A small committee of five was set up to verify this need and to figure out how best to get such a group going. Committee members included Randall Henderson of Palm Desert, editor of Desert Magazine and Harry C. James serving as Chairman. They invited all the people they knew who were interested in deserts to meet together at a picnic supper. Randall Henderson selected a spot for the supper at the entrance to Deep Canyon. Organizers had decided that if 20 or so people showed up, it would demonstrate sufficient interest to warrant an attempt to establish such an organization. More than 100 persons gathered around that historic campfire at the mouth of Deep Canyon on October 23 1954.

Some of the most outspoken conservationists of the day were present at that formative meeting, including renowned biologist Edmund Jaeger, Dr. Ernest Tinkham, Dr. Henry Weber, as well as Harry James and Randall Henderson. The initial discussion that day was about how best to protect Joshua Tree National Monument and other desert landscapes threatened by development and exploitation.

DPC founders understood that without a public knowledgeable about and with actual experience of the

desert, they would be fighting a losing battle to try to convince land managers and legislators to protect the desert from exploitation. Humans will only stand up for that which they know and love. Thus the heart of DPC’s mission is desert education. DPC attempts to educate the public and decision makers by disseminating information of all aspects of the desert. It does this, through informing members of events and lectures about the desert, by encouraging them to participate in DPC meetings and campouts, through the publication of quarterly Educational Bulletins about desert plants, animals, desert soils, land use plans and other desert-related topics. The DPC aims to cultivate appreciation and a sense of wonder and respect and a desire to protect the unique features, the archaeology and cultural history, the scientific, spiritual and recreational values of the desert.

DPC in a Nutshell:

The rich 60-year story of the Desert Protective Council would require a book to fully relate.

The DPC was incorporated as a non-profit 501(c)(4) membership organization in July 1955. At early meetings, the DPC elected 15 Board Directors, crafted their mission statement and established by-laws. Randall Henderson served as the first DPC president; other Directors included Dr. Henry Weber and biologist Edmund Jaeger. The new directors decided that a desert education organization required an Advisory Panel and they set to work nominating ten well-known people in their fields, including a university professor, a national park service naturalist and a director of a natural history museum. The group had decided that the Desert Protective Council would be membership-dues funded and managed strictly by a volunteer Board and members, which it continued to be for nearly 50 years. They agreed that to incorporate as a c4 would suit their goals better than as a c3 because the organization wanted to be able to speak out on all issues without constraint and involve itself in political lobbying as necessary. Over the decades, the size of DPC’s membership and participation has fluctuated, but its scope of interest to protect and preserve unique features and resources of all the southwest deserts remains the same.

Original membership dues were $1.00 annually, which included the subscription to the quarterly newsletter, the El Paisano, the ability to vote on all important policy decisions and on changes to DPC by-laws and an invitation to the DPC Annual Membership meeting. To this day, the DPC continues to publish a quarterly newsletter with the Roadrunner masthead. The charming roadrunner is pervasive throughout the west and early westerners’ affectionately called the bird Paisano or countryman.

The DPC began to publish the El Paisano in the Spring of 1955. In these fascinating 1950s quarterly volumes, the reader learns that the founders and members of the fledgling organization hit the ground running, immediately forming issues committees, informing themselves about issues related to their particular interest and taking action on controversial plans for the desert across Arizona, California, Nevada and Utah.

Desert Protective Council Board and Anza-Borrego Foundation staff meeting about Camp Borrego February 2014.

There apparently was no scarcity of ill-advised proposals for the desert even in the 1950s. Early newsletters document the political savvy and lack of timidity of the early Board and advisory panel members. Some of the problems DPC tackled in the early years, such as the threat from uranium mining in Joshua Tree and the battle to save the Grand Canyon from a dam, have been solved, but a plethora of new threats to the desert have arisen that could not have been conceived of in the 1950s. The onslaught of bad ideas for the use of our deserts has increased with the growing human population of the southwest. Exploitation of the desert for minerals and desert ground water, military expansion, poaching, rampant resort development, industrialization by massive energy projects and transmission lines, new freeways and the proliferation of off-road vehicles continue to fragment desert habitats.

The desert has been transformed over the past six decades. Many of the desert communities now sprawled across our four great American southwestern deserts did not even exist in the mid-50s.

A few highlights of DPC’s major campaigns over the decades:

DPC was an active participant in the work that led to the crafting of the 1976 Federal Lands Policy and Management Act (FLPMA). Prior to the formation of FLPMA, there was no Bureau of Land Management and no organized management or protection of America’s vast wealth of public lands. Off-roaders ran rampant, miners dug tens of thousands of mines at will, cities and counties dumped garbage where they pleased and hunting and poaching was out of control. Of course, the “multiple use mandate” of the BLM to manage our resources for a stunning array of “uses” is turning out to be the Achilles’ heel of FLPMA and our federal public lands continue to be coveted for all manner of unsustainable projects, including industrial scale solar and wind.

The Desert Protective Council was an active participant in the creation of the 1980 California Desert Plan. DPC made this a major campaign and through letters and lobbying by DPC members, the final California Desert Conservation Area Plan (CDCA) contained more protective language than was initially included in the bill. The CDCA, by creating use classes for various parts of the desert, added a layer of protection to millions of acres of the California Desert.

DPC was a major player in the 8-year battle to pass the California Desert Protection Act of 1994. Long-term DPC Advisory Panel Frank Wheat wrote the classic history of the passage of the CDPA: California Desert Miracle, which is a must-read for those interested in learning just what is involved in passing land protection laws in this country.

DPC spearheaded the successful campaign to stop the plan to cut a road from the top of the Santa Rosa Mountains down through Coyote Canyon in Anza-Borrego Desert State Park, thereby protecting a beautiful desert riparian area, an important haven for the endangered Peninsular Bighorn Sheep.

Over many discussions and committee meetings and consultations with several agencies and experts, DPC’s Anza-Borrego Committee evolved and broke away in the late1960s and became the Anza-Borrego Foundation (ABF). This successful land trust has worked to purchase and handed over 50,000 acres of private in-holdings in and around Borrego Springs to Anza-Borrego Desert State Park.

Between 2000 and 2004, the DPC participated as a member in the California State Park’s Department of Parks and Recreation Division’s OHV Stakeholders’ Roundtable, the task of which was to review all the regulations governing the CA OHV Program. This effort resulted in the group crafting legislation improving the OHV Program regulations. AB 2274 passed both CA congressional houses unanimously because of the support of the legislation by a wide range of stakeholders.

The recent decade:

In 2001, big changes occurred in the organization when DPC, along with two other conservation organizations, settled a lawsuit against the Gold Fields Mining Corporation on an inaccurately appraised land exchange to create a huge landfill in eastern Imperial County CA. Each organization obtained $1.6 million dollars from the settlement, with the stipulation that the funds would be used specifically for the protection of the environment and the public health in Imperial County. This lawsuit settlement heralded an opportunity for the DPC to become engaged in major desert protection and education efforts in this eastern corner of the California Desert. In 2004, the DPC Board decided to hire its first-ever full-time staff person to coordinate the expenditure of the “Mesquite Fund” for worthy conservation and education projects in Imperial County.

Native Americans protesting destruction of sacred sites with Ocotillo Wind project June 2012- DPC organized protest against massive wind project on public lands.

Over the past decade, the DPC has funded many major and minor projects in Imperial County, including donating $86,000 to finish building the interior of the Imperial Valley College Desert Museum in Ocotillo, CA. Through the Mesquite fund, the DPC granted $150,000 over three years to the Center for Biological Diversity for an Imperial County legal desert advocate. DPC supported several desert educational artistic projects, including Andrew Harvey’s Algodones Dunes traveling photographic exhibit and Christina Lange’s Visions of the Salton Sea photographic exhibit and Portraits of the Salton Sea book featuring the human residents and visitors of the Salton Sea area and their reasons for loving and living around the Salton Sea.

In 2007-2009, DPC contributed major funding to the Sierra Club to hire an organizer to develop a coalition and campaign against the building of a 500kv transmission line, the notorious Sunrise Powerlink, across Anza-Borrego Desert State Park. This campaign was successful in defeating the line through the state park, although sadly the Sunrise Powerlink has been strung instead over 100 miles through the desert and through San Diego’s wild backcountry, impacting the Cleveland National Forest and rural communities.

DPC-organized protest against the Imperial Solar project on public land sacred to the Quechan Native American tribe.

Between 2004 and 2014, DPC has been a major donor (over $140,00) to the Anza-Borrego Foundation’s Camp Borrego overnight environmental “tent” camp for fifth graders in Anza-Borrego Desert State Park. DPC’s funding has enabled over 900 Imperial Valley fifth-graders to attend the two-night overnight camp during which time the Camp Coordinator and her staff teach lessons about the plants and animals of the Colorado Desert. The students sleep in Mongolian yurts, view the stars through a telescope, take a hike in Palm Canyon, uncover fossils and learn about the career of paleontologist at the Paleo Lab and have a “scavenger hunt” at the State Park visitor center.

Volunteer Lou and Imperial Valley’s Sunflower Elementary students at the Anza-Borrego State Park Paleo lab “cleaning” “fossil” bones

DPC’s legacy project in Imperial County is the Salton Basin Living Laboratory Field Trip Curriculum (SBLL). In 2008, DPC contracted with a desert scientist/educator to a create place-based science curriculum about the geology, ecology and the human history of the Salton Basin that supplements Imperial County’s 4th through 6th grade general science curriculum. The SBLL Program is a model for place-based elementary school science education, which is sadly lacking in this country. Between 2008 and 2012, more than thirty Imperial Valley teachers took our SBLL teacher-training workshops and incorporated some of our materials into their science lessons. The curriculum has been introduced to more than a thousand 4th through 6th grade students and their parents. The field trip to Anza-Borrego Desert State Park is an integral part of the Salton Basin Program. The students have produced a variety of interesting reflections and projects based on the field trip experiences.

What has not changed over six decades?

The desire by corporations and interest groups to exploit the desert for its unique resources has not changed, although the type and magnitude of proposed projects have changed and, in view of the cumulative impacts from past and ongoing deleterious impacts, are much more menacing threats to what is left of the integrity of our southwest desert.

What has changed?

What stands out about the activism and ability of the early DPC to be effective was an on-the-ground intimate knowledge of the desert. Many of DPC’s early members lived in desert cities, but most of them joined the Desert Protective Council because they were avid desert campers and hikers and naturalists who ventured out into the desert regularly to explore and camp out under the stars. They knew the desert from personal experience and could testify with credibility to the values of its terrain, plants and animals and unique geological features. Some of the DPC regular general meetings included a campout or a naturalist-led hike, Annual Membership meetings, held in October of each year to celebrate the DPC’s anniversary, were traditionally held at some wonderful desert state park or national monument and included an overnight desert campout.

Today many sincere and committed desert activists and conservation organizations and their Board directors are urbanites. The large, well-funded national environmental organizations are mostly based in large cities, far from the desert. Too many conservation organization executive directors and staff have never spent time in the desert. Additionally, traffic patterns, work loads, information overload and technological distraction contribute to the fact that today’s conservationists and would-be land protectors do not have time nor do they make time to indulge in weekend camping trips or steep themselves in the experience of wild places. This lack of direct experience of the desert and disconnection from nature in general contributes to the lack of passion and will to fight the battles to protect our irreplaceable, wondrous deserts.

In view of the above circumstances and the urgent need to educate the public and our representatives about the importance of the desert, DPC recently spearheaded a campaign to raise seed money for an educational desert documentary. By the end of 2013, the DPC had successfully raised $25,000 seed money with which to engage award-winning filmmakers, Backcountry Pictures www.backcountrypictures.com to embark upon research and development of a desert documentary for television about the beauty, wonder and fragility of the Mojave and Sonoran deserts. The filmmakers, Sally Kaplan and David Vassar, finished initial desert scouting for filming locations this spring and are now working on the creative treatment. The next step will be to raise major funding from foundations and large donors that will be essential to the film production. This desert documentary, if picked up by PBS or the Nature Channel, could awaken a new interest in broad swaths of the nation-wide TV-viewing population.

One of DPC’s noteworthy founders: Randall Henderson

In California, Randall Henderson has been well known since the 1930s and respected as a

voice for the beauty, solitude and mystery of the southwestern deserts. Randall Henderson was

brought up in Iowa and in 1907 relocated to California to attend the University of California.

After graduation in 1911, he took surveying jobs along the Colorado River and worked in the

newspaper field. After WWII he bought the Calexico Chronicle of Imperial Valley and hired

J. Wilson McKenney to work for him. The two began taking weekend trips to the valleys and

mountains surrounding Imperial Valley. Over their weekend campfires they conceived of a

monthly periodical devoted to the desert, and actualized this dream with the creation of Desert

Magazine in 1937, which Randall edited for the next twenty years. This publication became

responsible for attracting adventurers from all over the country to the desert and in particular to

the Coachella Valley.

Henderson became alarmed at the increasing impacts to the Palm Desert area from his promotion

of the desert, and in 1954 co-founded the Desert Protective Council (DPC). One of his

avocations had been to visit all the native palm oases in the California and Baja deserts. In order

to do this, he stripped down a WWII Jeep, added oversized tires and created one of the first dune

buggy prototypes to get across soft desert sand to his oases. Soon others began imitating him

and thus started perhaps the original California desert invasion of recreational ORVs. Randall

wrote about his horror at what he wreaked on the fragile desert and in 1958, he handed over the

editorship of Desert Magazine to devote himself full time to writing about the desert. Henderson

served on the DPC Board of directors in the 1960s and edited the DPC newsletter- the El Paisano

between 1970-1975. For many years the DPC published Henderson’s Desert Magazine columns

Between You and Me in the quarterly newsletter, the El Paisano.

To learn more about the Desert Protective Council and its current and past projects, or to join or

donate: www.dpcinc.org or call or email DPC’s Conservation and Projects Coordinator, Terry Weiner at (619) 342-5524 or terryweiner@sbcglobal.net.

To read the PDF version of this article, click here and here.

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!

This Desert Protective Council and the people who ran it are all but gone now. Their Facebook page hasn’t made any comment since December 2016. Here is their final Facebook entry:

“After 62 successful years of being a staunch voice for protection and preservation of our southwest deserts, the Board of the Desert Protective Council is in the process of dissolving the DPC…read more below…”

There were a mere 11 people who mourned their loss.

If there is truth to the comment that the Board of DPC is thinking about dissolving the DPC – I am truly disappointed. For so many years the DPC was the voice of the public in all efforts to protect the desert resources and get public agencies like the BLM to be responsible in managing our public lands – especially our deserts. Today, the need to be heard is even more critical as more and more use and development pressures invade these public lands. Terry Yonkers (Assistant Secretary of the Air Force, ret. and past DPC president).

Terry A. Yonkers, how do you feel about Michael Moore’s documentary, “Planet of the Humans” and the various bogus technologies that comprise the not so green energy industries who are nothing more than a marketing scheme ??? Do you feel betrayed ??? Just curious.