I locked myself out of my house the other day. I stood there for a minute, and then walked the front door and then to the side door. All locked. Kinda funny really. We lived for over 10 years in a house that had no lock on its door, and when we moved next door we had locks but never used them until now. Recent stories about break ins, thefts and even entire contents of a home being stolen have prompted us to change our habits. It has not been an easy transition.

When I first moved here I left me keys in the ignition of my car when I went into the post office, into City Market, and certainly when I was parked in my own driveway. I always knew where the keys were that way. And when I lived 30 miles from town it also meant in an emergency there was no frantic key search.

We stopped leaving the keys in the ignition in the driveway a few years back when a patron of the Outlaw Saloon slept in one of our vehicles out back during a February snow storm. For months leaving the house became a few minutes of searching for keys. It is a hard transition having to lock doors. You lose your keys, you get locked out without your shoes off….. Learning to lock doors is an uncomfortable transition full of symbolism. And it means no more unexpected treats on the kitchen table left by friends passing through town.

What makes you “local” anyways?

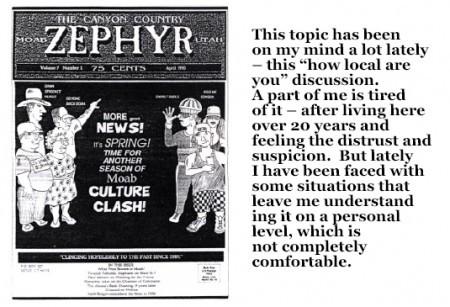

This topic has been on my mind a lot lately – this “how local are you” discussion. A part of me is tired of it – after living here over 20 years and feeling the distrust and suspicion. But lately I have been faced with some situations that leave me understanding it on a personal level, which is not completely comfortable.

We moved a lot when I was a kid. I was born in the SF Bay Area while my dad was in grad school. Then we moved to NW Massachusetts so he could teach. A few years later we moved back to the Bay Area, and lived on the Peninsula for most of my younger school years. And thanks to my father’s job and my mother’s decision to find work that allowed her scheduling freedom we traveled all over the world almost every summer. I spent time in the East Bay Area for college, a bit over a year in overseas after that…and eventually I ended up in Utah. First in Alton, and eventually Moab.

We moved a lot when I was a kid. I was born in the SF Bay Area while my dad was in grad school. Then we moved to NW Massachusetts so he could teach. A few years later we moved back to the Bay Area, and lived on the Peninsula for most of my younger school years. And thanks to my father’s job and my mother’s decision to find work that allowed her scheduling freedom we traveled all over the world almost every summer. I spent time in the East Bay Area for college, a bit over a year in overseas after that…and eventually I ended up in Utah. First in Alton, and eventually Moab.

When I was 21 I met an old man somewhere between Alice Springs and Katherine, Australia who had never left the tiny town we were standing in. I remember that striking me as amazing. I was envious. The reality of reaching 80+ years old and having only spent time in around 500 square kilometers was foreign and amazing to me. It really got me thinking about sense of place and belonging.

I’m starting to understand the “old versus new” tension in Moab. I accept, and in many ways deeply appreciate, that I will never be a “true” local. With my background there is really nowhere I am “local”. I have some envy for those who have been born and raised here and know the it intimately and have connections to places through generations. In the modern Western world being connected over a long period of time, through generations, is no longer common. It lends a different perspective and understanding to a place that is not necessarily better than other perspectives, but it is different and extremely valuable. Having long history with a place leads to a deep caring for the long term future of the place.

My husband Ray has roots in Moab. His great grandfather was Moab’s first doctor. His Uncle Mitch and Aunt Mary started Tag-A-Long Tours, one of the foundational businesses of our current tourist economy. But Ray’s grandmother, Mitch’s sister Ramona, moved to Walnut Creek and Ray was born and raised in the SF Bay Area. He started coming here in 1974 to work summers for Mitch and moved here soon after school. He’s been here over 35 years, but is Ray local?

A part of what sets a local (from any area) apart is shared experiences and investment in the community. You can have roots, like Ray, but shared experiences do define your understanding of place. Whether it is learning to navigate the dirt roads around Moab with or without a four wheel drive, of river expeditions and rescues, of amazing waterfalls on the river road, of the sound and ground shaking of a huge flash flood in Mill Creek, of holding down 2 or 3 jobs just to stay here (and still being here), when you know what people mean when they give you only 4 digits for their phone number.

The Todd River runs through Alice Springs. When I was in Alice I was told that those who saw the river flow some number of times (I can’t now remember if it was 1 or 3) were never leaving. That “river” is a huge sandy wash that rarely flows.

I now understand better some of the distrust and suspicion I felt from time to time when I first moved to and started working in Moab. Recently, to my surprise I have found myself feeling what I suspect are similar feelings of distrust and suspicion, possessiveness and defensiveness at times. Unfortunately I probably have allowed those feelings to impact my behavior from time to time as well. I am not very comfortable with that behavior in myself, and I certainly do not like those feelings. But I think I am starting to understand where they come from.

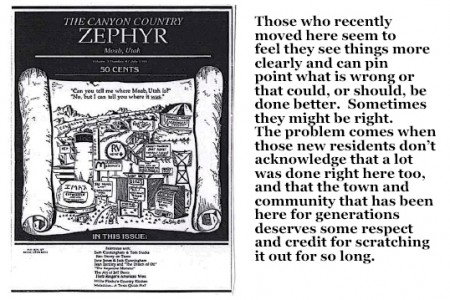

I heard someone in Moab once say you’re a local here when you have started at least one business and failed. Perhaps that alludes to a piece of being “local” – it is being invested in what is the community and helping find solutions to challenges. Being invested can manifest itself in different ways for different people, old Moab families or newly arrived residents. For me, being invested in the community means that you seek understanding and solutions and have taken the time to learn, at least as much as is possible, the history of the place and people. Probably it is why I read the Zephyr so much when I first arrived. This paper has always had old photos and stories from people who have lived here since Moab was called Moab. I found books like The Far Country and have scoured The Grand Valley Times to learn about the people and place I ended up calling home.

I thought I’d go out on a bit of a limb and write about this now. I’d write about it while tensions are a little high and the topic is not very easy. I’d write about it because sometimes it is good to air those unspoken, uncomfortable things. I have no solutions (though I wish I did), but sometimes airing those things transforms them a little bit into something else, hopefully something better or at least less distasteful.

We all agree…”they” are all wrong …or are they?

Two months ago in a public meeting about public land use a participant stated that it would be better if it was 30 years ago because then all the people interested in wilderness and conservation designations wouldn’t be here. This oversimplifies the issues, and more importantly makes it impossible to communicate about the challenges that face us all. I wish it was 30 years ago here too, and I only got here around 22 years ago.

There was something comfortable about going to the grocery store or post office and recognizing over half the people in the store. Lately I find myself out in town, even in winter, surrounded by a sea of faces I don’t recognize. When you have been used to recognizing most faces when you run errands (even if you may not actually know the people behind those faces) it is a little disconcerting to realize that you recognize almost no one in the market or post office in winter. It isn’t a bad thing, and I certainly get errands run a little faster when there are not lines at checkout. I do miss the impromptu conversations with all kinds of people I haven’t seen in ages.

There was something comfortable about going to the grocery store or post office and recognizing over half the people in the store. Lately I find myself out in town, even in winter, surrounded by a sea of faces I don’t recognize. When you have been used to recognizing most faces when you run errands (even if you may not actually know the people behind those faces) it is a little disconcerting to realize that you recognize almost no one in the market or post office in winter. It isn’t a bad thing, and I certainly get errands run a little faster when there are not lines at checkout. I do miss the impromptu conversations with all kinds of people I haven’t seen in ages.

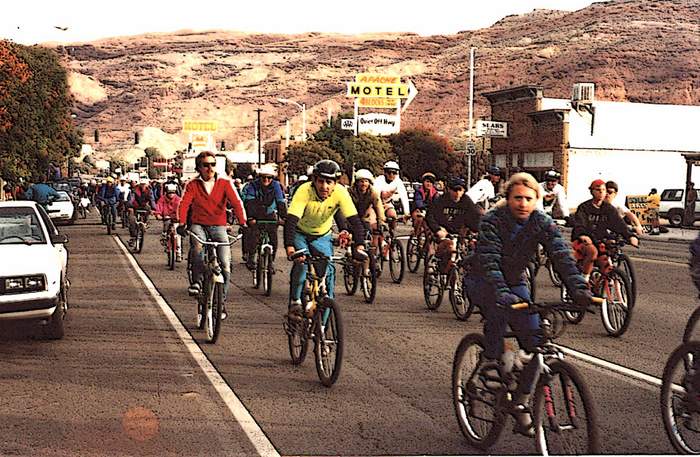

As a Conservation District Supervisor, from time to time I have the privilege of meeting and talking with farmers from all over the state. I am definitely the odd duck in these meetings. The first state convention I went to I was mostly was quiet and listened. I learned a lot. I learned about what is grown where in this state – there is more agriculture here than most may realize. There is a deep understanding of and respect for the landscape within the agricultural community that is not readily recognized or understood by newcomers from urban and suburban areas. Last year I was asked to present to the convention about Grand County’s agriculture. I talked about how for a small rural county our problems are more urban than most of rural Utah. I talked about bees, and the Youth Garden Project, that we produce some cows in Grand County, and sheep but our agriculture is mostly small compared to the rest of the state and we herd more bikes than cows anymore. And about how much of the small amount of agricultural land in Grand County now grows houses rather than food.

I listened to presentations from the 6 other Conservation District zones. Some about entire regions of the state, others about smaller projects. I realized that while my upbringing could not be more different and my journey to my place in Utah has been a little off the wall; while I grow native plants, and most everyone else in the room grows cows, hay, chickens or other crops; that by being there, by listening and learning, I was starting to understand more about Utah. While our starting points may be very different we all share challenges of how to get water to our crops, how to control weeds, how to make a living in agriculture.

One thing at the many meetings I have been to, Conservation District and otherwise, that I have noticed is a tendency for issues to be raised for discussion with the preface “I know we all agree,….”. Often I don’t agree, sometimes I quite vehemently do not agree, but that usually is not something I am comfortable raising in a room full of 400 people (or sometimes even in a smaller group of 10). Usually when I hear something beginning with the phrase “I know we all agree” I am pretty sure I am not the only one in the room who doesn’t agree. There is a danger in assuming membership to a group implies all members agree on all topics. Speaking for myself I know I am a mass of contradictions when it comes to land use topics.

I know people assume they know my opinions since I am a transplant; or because I am a boater; or because I grow native plants for revegetation; or because I have spent a number of years working on Russian olive removal and regenerating native plant communities along Mill Creek in town. I suspect they would be surprised if they knew my actual thoughts on many topics, though usually I am not asked.

By labeling ourselves and each other as real local and newcomer assumes all of us “newcomers” agree, as do all the “real locals” we highlight what divides us. And communication stops.

Are we just repeating ourselves?

When I first started working in Moab on desert and riparian regeneration I spent some time researching the land and water use in the Mill Creek watershed. I learned a lot. Mill Creek through town has not always been as it is today. At the turn of the century in the Grand Valley Times I found an article about floods widening and deepening Mill Creek by as much as 5’+ in one event. There were stories with complaints from miners on the mountain upset at the overgrazing from the tens of 1000s of sheep on the mountain. Jim Walker told me stories of 500 West being deep in sheep poop for days when the sheep were driven from the range through town to the rail lines.

I learned about various ways that water was used from the creek, and all kinds of ways people tried to get to it in the upper reaches, and in town to steal it. In more recent history, I learned about plans for a dam to be built in Mill Creek Canyon above the power dam, I think near the confluence of right and left hand. I learned about the community fights and saw articles with could have been published just this past winter and the rhetoric might have been mistaken for new news. And from what some locals in the 1990s told me, it sounds like the community was as divided about the dam as it is now about oil and gas extraction. After Teton Dam collapsed the plan was changed, and we now have Ken’s Lake.

In these same papers were stories about the first power in town, about dust storms, bridge wash outs, and uranium. The boom period of the town was apparent, and then the collapse. The challenges of the 80s, of no jobs, people leaving town. And then tourism.

Blame, responsibility or just problem solving without a crystal ball?

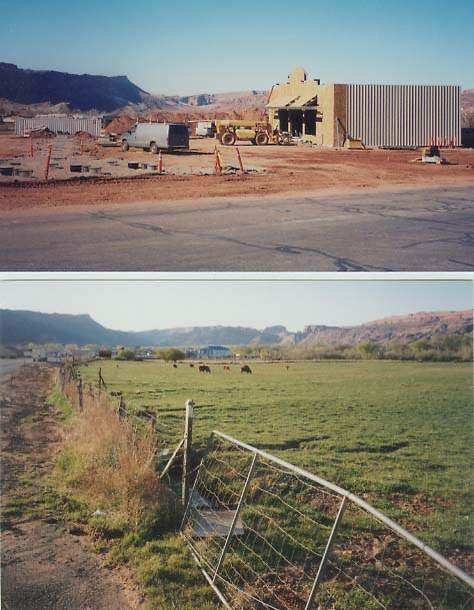

Remember it was “true locals” who 30 or so years ago invited the world to Moab because the uranium boom busted and there were no jobs here, plenty of housing just no work. One thing this place certainly has is some amazing and unique scenery to hike, bike, raft, and four wheel to visit even more amazing places, and it certainly seemed wise to capitalize on it. Our current troubles with housing and infrastructure started with those seemingly benign invitations. How could people coming to visit possibly be a problem? There were fewer people traveling then; base jumping and slack lining didn’t exist; OHVs and ATVs were not commonly owned; and there were no companies specializing in manufacturing personal rafts and stand up paddle boards. So many things that could not have been anticipated then have changed everything. Thanks to the Travel Council advertising paid for by transient room tax dollars, and an ever growing world population with apparently bottomless disposable income to come play, the solution to Moab’s economic woes of the 80s has become a monster.

Because of decisions made to invite the world to play in Moab more people have moved here – for work, for retirement, for a lot of reasons. Without those transplants there would not be enough workers for the jobs now created, and there would not be enough population base in the ever shortening off season to keep Moab businesses in business.

Those who recently moved here seem to feel they see things more clearly and can pin point what is wrong or that could, or should, be done better. Sometimes they might be right. The problem comes when those new residents don’t acknowledge that a lot was done right here too, and that the town and community that has been here for generations deserves some respect and credit for scratching it out for so long. People whose fathers and grandfathers, mothers and grandmothers lived here before there was power or a water system, when Main Street was dirt and there were few stores in town, when Uranium came and the first big boom hit Moab and then faded leaving children with no way to make a living. People who built our infrastructure, roads, water system, all those things that make the town possible. These families are still here, and while they may have a different appreciation and perspective on the landscape and how to care for it, they made it here and care for this place deeply. Listening to their stories and perspectives about how we got to where we are today is a critical part of figuring out how to be prepared for new challenges tomorrow.

When it comes down to it – we all live here, whether by birth or by choice (or both), and as a community we face some pretty big challenges. Anyone who owns a business today, or simply tries to drive down Main Street, knows that Moab is booming. And as with all booms, this boom is stressing infrastructure, and meaning nearly every business is hiring or needs more help. The last big boom here resulted in trailers everywhere (among other things). One of those is still out back behind my house. Our sewer plant needs replacing. Everyone I know, whether working for a tourist oriented business or not, is so over the top busy that they have little time for anything, even getting out on the water or for a hike. And we have to lock our doors when we leave the house now.

Regardless of the source of these challenges – the decision to encourage tourism made by some who have been here the longest, or the decision of those of us who have moved here lately to fill jobs or to move here just because we like it here – we face these challenges now as a group. I hope we can all move past labels and blame and start to really communicate with each other. While Moab is inexorably changed, all booms do bust eventually, and then all we have is community to keep things going.

Kara Dohrenwend is a regular contributor to the Zephyr. She lives in Moab, Utah.

To read the PDF version of this article, click here.

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!