Consider, for a moment, the horse. Your average horse is still a romantic figure, evoking a rich historical relationship of labor, war, and transport. Horses made the journey across the Oregon Trail. Horses marched into battle, and lay among the war dead. They drove the plows and hauled the crops to market. Horses carried the world through centuries of industry.

I love to see horses out in the fields. I hardly ever see more than a handful at a time, grazing among the tall grasses, and pawing the ground. Occasionally one starts and prances toward the fence line, for reasons left unknown. But I have never seen a horse at work in those fields. I have never seen a horse engaged in industry, and I doubt that I’m the only one. The population of horses in this country, which was enormous in the 19th century, fell off by nearly half in the first 30 years of the 20th century, and then by 90% by the 1950s. Their services were rendered useless, in a span of 50 years, by technological innovation.

And that brings me to why I am thinking about the horse today. I am thinking about the horse because it was once essential, and thanks to technology, now it is only lovely. The horse is now only a reminder of a less efficient time. And soon the average worker will be the same.

Recently, I read an article from The Guardian about the so-called “end of capitalism.” The author, Paul Mason, suggests that, just as the marketplace of capitalism arose from the ashes of feudalism, it too will be overtaken by a new form of economy—post-capitalism, he calls it. And post-capitalism would rise because of the freedom and the open-source nature of new technologies. The new information age, he posits, demands a free and open collaboration of individuals, and it resists privatization and the creation of wealth. “Information,” he writes, “is a machine for grinding the price of things lower and slashing the work time needed to support life on the planet.” We are increasingly powered by information—data, algorithms, etc.–and because information is not subject to supply and demand, the x and y axis of the old economic models, the price of life will need to be reckoned in an entirely new way. The 3-D printer is the most obvious harbinger of this new world. Assuming the printers themselves get cheaper and cheaper over time, they will allow individuals and companies to create a virtually limitless supply of goods, using free information, and no labor. So what, in an economists’ world, is the “worth” of those goods they’ve produced? How do you have an economy with no need for a labor force?

I am not an economist, and so reading Mason’s article was an ambivalent experience. He seemed to believe that the future was likely to be rosy for the average person, once we all embraced the idea of this new economy, where all knowledge is openly shared and machines labor for our benefit while we collectively reap the profits. But I couldn’t quite make that jump.

This wasn’t the first article I’d read about the coming end of human labor. It’s a common topic, as technology pushes forward, stretching far beyond human capabilities. What laborer can compete with the 3-D printer? Even sweatshops in India and China would be shuttered by this new, free labor source. What office clerk can keep up with the ever-enhancing organizational skills of our “smart” technology? Two years ago, researchers at Oxford University predicted that machines could perform 45% of all U.S. jobs within the next twenty years. When you consider the most widely held jobs are in retail, food and beverage service and office work, twenty years almost seems a conservative estimate.

Interestingly, the famous British economist John Meynard Keynes foresaw this shift 85 years ago. He wrote an article, “Economic Possibilities for Our Grandchildren,” in 1930, which predicted that, by 2030, humans would have entered a state of “technological unemployment.” He imagined that workers might labor for 15 hours a week, merely to save themselves from boredom. He too, was largely positive about this future utopia, referring to it as the “daylight” after the long “tunnel of economic necessity.”

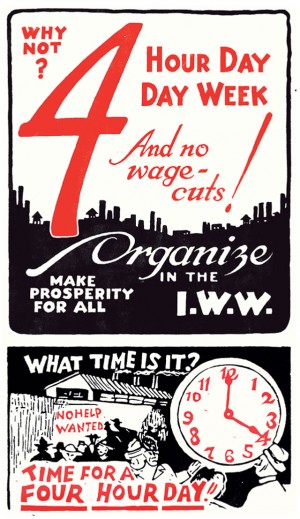

Of course we’re supposed to be happy about the end of work. Who likes work, after all? Most jobs are just endless days of sequential, boring tasks. We, as Americans, work harder than anyone in the developed world, for fewer benefits, and it all seems such a waste. After all, as Benjamin Franklin said, “If every man and woman would work for four hours each day on something useful, that labor would produce sufficient to procure all the necessaries and comforts of life.” And, probably, every person working four hours a day would provide enough productive work to keep all the wheels greased and money flowing. But somehow, four hours of work each day isn’t enough to earn an income that could support a family. And no one has quite explained to me how, in this utopian future without any jobs at all, the average person is meant to survive.

The one constant, through the ages of feudalism and capitalism, is wealth. Whether that bounty of riches was held within the feudal walls, or the Church, or the Monarchy, or later, the Corporate Monopoly, wealth has always existed and it has always been concentrated somewhere. Capitalism was supposed to free up a great deal of that money, moving it and redistributing it constantly through the exchanges of goods and services, but in practice, the wealth tended to stick in certain pockets for the long term, and fall frictionless through the pockets of others.

The one constant, through the ages of feudalism and capitalism, is wealth. Whether that bounty of riches was held within the feudal walls, or the Church, or the Monarchy, or later, the Corporate Monopoly, wealth has always existed and it has always been concentrated somewhere. Capitalism was supposed to free up a great deal of that money, moving it and redistributing it constantly through the exchanges of goods and services, but in practice, the wealth tended to stick in certain pockets for the long term, and fall frictionless through the pockets of others.

In the modern form of capitalism, most wealth is illusory. While the very rich and very frugal may be able to count their net worth in actual dollars, sitting in a bank vault somewhere, the rest of the population relies on credit. Your home is likely paid for, technically, by the bank, and if you were to fall behind on making payments, your bank would take it away from you. You are, in fact, renting that house from the bank until the day you make your final payment or until you sell it to some other bank-financed individual to recoup what you’ve put into it. Same story with anything bought on payments—cars, large appliances, home renovations. Practically every daily purchase is made via credit card, which, if it isn’t paid off fully each month, accrues interest. So your coffeemaker, which might have “cost” $90 at the store, ends up costing you another $15 a year, every year, until you pay it off. And almost no one is paying off their debt. As of last November, the amount of debt outstanding in American households was $882.12 billion.

So, the first issue of “transitioning away from capitalism” isn’t so much about how wealth is reckoned, and whether we can spread it around. It’s about how debt is reckoned in this new society without jobs and, correspondingly, without incomes.

A universal basic income is one suggestion that comes up a lot. With a very low, maintenance level of income going to each and every citizen, then the terror of insolvency that haunts most of the current workforce would be gone. Those who wanted to work part-time could. Those who wanted to start a new business could. And those who wanted to fart around and play video games, or drink themselves to death could do that too. And with a substantial relief to the overburdened, patronizing social safety net we have now. Much the same way that it seems to be more cost-efficient to simply give homes to the homeless and cash to the poor, the simplest way to cushion the fears of the job market may be to give everyone an income.

It’s a compelling argument, and it’s made headway in some European countries and among talking heads here in the States. But, honestly, I just can’t see it happening anytime soon. The American mindset is too stuck on the idea that money is a reward for work—despite all the evidence of the rich, for whom “money makes money,” to show it isn’t.

One of the best suggestions I’ve read was to bring back the Works Progress Administration, Roosevelt’s job-creation program, to put the millions of jobless to work at necessary public tasks—creating works of public art, repairing infrastructure, care-taking for the elderly and ill, etc. Even creating a public website full of tasks that need doing, and payment provided for each task a citizen takes on. It’s certainly a more concrete vision than just setting loose all the formerly employed on a life of total leisure. And it’s the best I would hope for, even if it isn’t what I expect—not in a world so wary of massive public investments.

A more likely “positive” solution, as far as I can see, is that, as real jobs disappear, they will be replaced by the endless creation of more nonsensical jobs. This way, everyone will feel cozy about deserving their portion of the pie without being faced, head-on, with their new uselessness in a society powered by machines.

You know how, when you walk into the DMV, there are about fifteen people milling about behind the counter, but only one person is standing at the desk? I’m betting that’s what the future will look like. One person in each office will be in charge of making sure that the machines are chugging merrily along. Twenty other people will be responsible for the “administration” of that person. They will make more money than him. Three hundred other people will be tasked with running around, aimlessly fetching things and handing them off to each other, praying no one notices them long enough to fire them. They will make very little money. But, at the end of the day, the lowly workers will have their meager income to take home, the administrators will have a handsome check of their own, and the one guy who actually understands the purpose of the company where he works will sigh to himself at the meaninglessness of it all.

Could I be wrong? Could it all work out for the best? I suppose. If a sizable chunk of the wealth that is currently in the sticky hands of the aristocrats were concentrated instead into the government, and if the government could stop bickering and fussing long enough to focus its attention on helping its citizens navigate the new, jobless world, then perhaps we could all deal with a future of leisure. Perhaps we could sort out ways to keep ourselves useful, through public service and creativity. We could keep everyone afloat through some basic income and provide work enough to keep boredom and television from enslaving our days. Sure. It could happen.

But if we’re going to try for a utopia, or at least a not-total-crap future, we’d better start talking about the harsh realities of this new technological tomorrow today. Because the changes are happening whether we talk about them or not. We plebeians are fast outliving our necessity in this brave new world. And though the ruling classes will be very sorry to do it, if we can’t figure out some way to make ourselves useful, it’s out to pasture for these former workhorses. Or worse, the glue factory

Recommended Reading:

(The Guardian) The End of Capitalism Has Begun

(Atlantic) A World Without Work

(Vice) Who Stole the Four-Hour Workday?

Tonya Stiles is Co-Publisher of the Canyon Country Zephyr.

To read the PDF version of this article, click here.

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!

We at the Zephyr (or all of us “our only hope is catastrophe” types) might consider claiming victory. Have you noticed how “Growth” has disappeared as the ultimate solution to everything? Ever since 2008, I think the elites have started accepting that humans need to be replaced, and are trying to figure out how to tell us. I don’t think they’ve yet figured out how to do it peacefully, but technically, it shouldn’t be too hard (except for a few run-of-the-mill genetically modified armageddons here and there.) Here’s two more recent items to add to Tonya’s list:

http://www.wired.com/2015/07/crispr-dna-editing-2

http://www.mirror.co.uk/news/uk-news/sex-robots-the-norm-50-6190575

A good story, thanks.

I think your intuition about where technology is taking us, along with your apprehensions about what that means, are well founded.

Tonya, yer a commie! But seriously… your vision of the future with one worker and a hundred administrators already exists. It’s called the University of Colorado at Boulder. Read my book for more horror stories of working the bureaucracy….(“Rogue’s Gallery”)