Jerome Arkansas

Mom, her mother and father, two sisters and six brothers, and the other Fresno Fairground horse stable inmates left Fresno on October 20, 1942. My uncle Ken, then 16, recalls the very long train that carried them from Fresno to Arkansas. En route, the train traversed the railroad engineering marvel known as the Tehachapi Loop in Southern California. In order to negotiate the steep grade in the Tehachapi Mountains, the tracks form a loop which enables trains of sufficient length to cross over themselves.

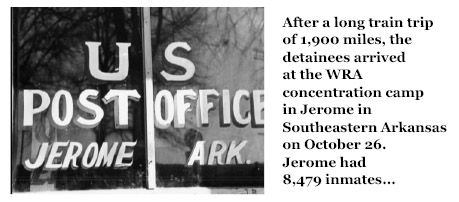

After a long train trip of 1,900 miles, the detainees arrived at the WRA concentration camp in Jerome in Southeastern Arkansas on October 26. Jerome had 8,479 inmates, and a nearby WRA camp at Rohwer Arkansas, also designated for San Joaquin Valley California residents, housed 8,475 prisoners. Similar to life at Topaz in Utah, Mom, her family, and the other newly arrived inmates of the Jerome WRA camp set up the means to carry on with their lives in this strange new environment.

Mom was 20 years old, and spent time tending to family matters, such as caring for her younger siblings, sewing clothes, attending classes, and doing a variety of household chores in their shared family housing barracks.The inmates who had jobs could save up their wages of $12 to $19 per month to purchase items from Sears and Roebuck, Spiegel, and Montgomery-Ward mail-order catalogs. Clothes and material to make clothes, as well as, many other items for daily use, unavailable from the US Government, were popular purchases.

Mom didn’t speak much to me about her day-to-day existence during the 11 months she and her family spent in Jerome, so from her silence I can only imagine how difficult life was for a young woman in those circumstances. The construction of the barracks was rudimentary: wooden-framed with tar-paper wall covering, barely enough structure to provide shelter from the elements. It was too cold in the winter, too hot in the summer, and too uneventful (boring) most times. Personal privacy was unknown, and no indoor plumbing or toilet facilities contributed to the discomfort and indignity. The WRA rules stipulated that multiple families shared a single barracks unit, leaving little privacy for typical family living – the events, the conflicts, the celebrations, or the grief.

In addition to all the personal inconveniences, I can also only imagine the anger and frustration each inmate must have felt as a result of their unlawful, forcible imprisonment, since formal charges were not filed, and due process was completely absent. The fear associated with an unknown future, the psychological and physical disorientation, and the shock, disbelief, and humiliation of being thrown into prison for no reason, all contributed to a miserable existence for the inmates, but gaman.

Familial and societal norms for usually tightly-knit Japanese-American families were disrupted, as the pressures of camp life destroyed the traditional nuclear family (grandparents-parents-

Women could no longer cook for their families – their children, parents, and husbands. The basic US Government-issued, Army-surplus,canned ration food supplies provided little in the way of flexibility for preparing traditional Japanese comfort-foods. In the early years of the camp experience, traditional Japanese food disappeared from the diets of the inmates. Potatoes were the staple of mess hall dining, replacing white rice– “gohan”, beloved as THE staple of the Japanese diet.

Minor mess hall rebellions throughout the WRA camp system managed to get rice added to the food supplies. However bleak, the overall food situation eventually improved as opportunities emerged for remarkable creativity in how to make-do with basic food provisions. In a culinary rendition of overcoming shikataganai and gaman, camp inmates were able to reverse an unsatisfactory situation. The original US Army mess hall cooks, assisted by inmates with cooking experience, were able to create interesting versions of Japanese food using whatever basic ingredients were available to them. For instance, canned Vienna sausages, frankfurters, and spam became wienie o-kazu (a dish made of meat, vegetables, and soy sauce), and wienie and Spam sushi. Leftover rice also provided the raw materials for surreptitious sake-making distilleries tucked-away in secluded corners of mess halls. Over time, inmates became the mess hall cooks adding to the diversity of Japanese concoctions that could be devised using a wider variety of raw materials. Knowing what a terrific cook my Mom was, I just know she had a hand in invigorating the mess hall menus to her and her family’s liking.

During their stay in Jerome, Mom and her brothers and sisters were also compelled to complete the “Loyalty Questionnaire”. A single, ill-timed and ill-managed recruitment effort by the US Army for combat troops for the 442nd Regimental Combat Team resulted in only 31 volunteers. Because one of the reasons for the WRA questionnaire was to identify “loyal” inmates for service in the US war effort, which also included the Women’s Army Corp, the Women’s Army Air Corps, and the American Red Cross, women over seventeen years of age also had to answer Questions 27 and 28. I never had the opportunity to ask Mom specifically about this, but I can easily envision her answering “No” to both questions. One or more of my uncles could also have done so, making them members of the “No-No Boys (and Girls),” and thus making them eligible for segregation. The Takeuchi family was able to remain together, but among those groups identified for segregation. On September 25, 1943, Mom and her entire family were transported from Jerome to Tule Lake California, the newly designated WRA Segregation Center. On September 29, they arrived in Tule Lake California after travelling 2,300 miles on another train.

Tule Lake California

Three thousand prisoners at the Tule Lake California WRA center answered No and No to Questions 27 and 28 of the “Loyalty Questionnaire”, so the WRA decided to make Tule Lake the Segregation Center to imprison the“No-No-Boys”, the allegedly disloyal or trouble-maker inmates.The Tule Lake WRA camp was originally established in Northern California near the Oregon border as one of its ten concentration camps. In 1943, the camp was re-designated as Tule Lake Segregation Center. To make room for the 12,000 additional inmates who were arriving as a result of their “improper” responses to the Loyalty Questionnaire, “loyal” inmates were transported to other WRA camps at Manzanar in Southern California, and to Poston and Gila River in Arizona. Eventually, 18,789 inmates called Tule Lake home in 1944, making it the largest and most controversial of the ten WRA camps. As the camp with the highest level of collective and vocal resentment against the unlawful incarceration carried out by the WRA, Tule Lake, despite its large population, only contributed 57 inmates to the US Army’s 442nd Regimental Combat Team.

Amy and John arrived at the Tule Lake Segregation Center within 14 days of each other, and as with their arrivals at their previous WRA camps, they and their families went about the business of trying to re-establish the semblance of a normal life in yet another new concentration camp. For the men and boys, normalcy included baseball. Uncle Ken and Dad played on different baseball teams, loosely organized around “home” geography: Ken was on the “Nippons” team from Sacramento, and Dad played for the Iwakuni Japan team.

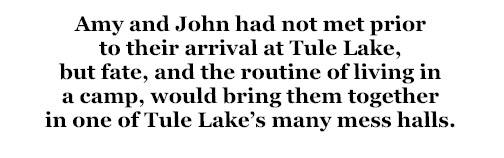

Amy and John had not met prior to their arrival at Tule Lake, but fate, and the routine of living in a camp, would bring them together in one of Tule Lake’s many mess halls. My conversations with Mom and Dad yielded little about their private lives related to their courtship during the period between the time they arrived at Tule Lake in September 1943 and their marriage in February 1946 (… not a complete surprise).

Dad had taken a job as a cook in the mess hall where Mom was employed as a food server and waitress. They met, became acquainted, and over time, this “office romance” blossomed and flourished. Other than what I believe to have been their understandable individual and collective efforts to make the best of a bad situation, that is, a young couple seeking some privacy during their courtship, I learned little. They were able to date, despite the restrictions imposed by life in a prison, as there were movie theaters, canteens, cafes, shops, and activities like dances and other social activities, and I know my Dad was always a gentleman. A community of nearly 19,000 residents, essentially a small city nearly 4 times population of Moab, was able to offer small measures of privacy, if nothing more than what can be afforded by the anonymity of being two people in a crowd of hundreds or thousands.

World War II ended with VJ Day (Victory over Japan Day), on September 2, 1945, with the formal signing of Japan’s surrender on the deck of the battleship USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay. VJ Day also signaled the end of the need to maintain the WRA concentration camps. Actually, the administrative steps to close Tule Lake and the other nine WRA camps began in January 2, 1945 when the WRA reopened the West Coast military security zone to Japanese Americans. On July 13, 1945, the WRA announced that all of the camps were to be closed between October 15 and December 15, 1945. The exception was Tule Lake, which for a variety of reasons, including a number of inmates slated for repatriation or deportation to Japan, was kept operational past December 1945.

John and Amy were married in a Buddhist ceremony on February 24, 1946, at the still open Tule Lake Segregation Center. The wedding photo included with this article shows the wedding party, and several of the WRA barracks in the background. The wedding reception dinner consisted of Spam with Hostess cupcakes as the wedding cake.

Mom and Dad remained at Tule Lake until their March 18, 1946, departure for their new home in Reedley, California, 475 miles from Tule Lake, and about 30 miles Southeast of Fresno. My aunt Erma, who left Tule Lake on January 18, 1946, recalls that Mom asked her to send her some nylon stockings for her wedding. Erma and the Takeuchi family had temporarily settled in Reedley after their departure from Tule Lake. Erma recalls going into Reedley to shop for Mom’s nylons, and that the store-keeper, still harboring animosity towards Japanese-Americans, was less than gracious to her. Beyond the store-keeper’s rudeness, she also recalled that there were no nylons to purchase anyway, as nearly all nylon was diverted to the war material supply effort to produce items such as parachutes.

After Tule Lake

The Tule Lake WRA concentration camp was officially closed on March 20, 1946, two days after the newlyweds, John and Amy Mikuni, departed for their new life and home in Reedley. Executive Order 9742 was signed by President Harry S. Truman on June 26, 1946, officially terminated the mission of the War Relocation Authority.

As their departure from Tule Lake approached, the Takeuchi family contacted Herman Neufeld, who purchased the Takeuchi ranch prior to their departure for the concentration camps. Mr. Neufeld and neighbor Joe Bergin, who operated a chicken business in Reedley, hastily converted 3 large chicken coops into living quarters for the Takeuchi family. This was quite a housing journey for the Takeuchi family: horse stables, to tar-paper barracks, to chicken coops! They stayed in this temporary housing for about 6-months, moving several more times before they eventually settled in Fresno. Dad’s two sisters and their families returned to their homes in Oakland and Los Angeles, respectively.

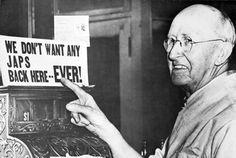

Anti-Japanese sentiment among the citizens of California was still running high, so the environment for a smooth transition back into non-camp life for all former concentration camp inmates would be difficult. The “We Don’t Want Any Japs Back Here – Ever” sign in the attached photo was typical of the reception awaiting returning, formerly-imprisoned Japanese-Americans. Notable exceptions to the hostile population were, of course, Mr. Neufeld and Mr. Bergin, as well as, another gentleman named Clay Comer, a close family friend of the Takeuchi family. Clay remained loyal to his Japanese-American friends, regardless of what was occurring around him and in his own family, and was considered to be an honorary member of the Takeuchi family.

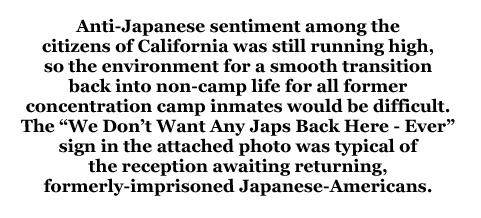

I was born in Reedley in 1947. Mom and Dad then moved to two additional rental homes and farms in Fresno, and my two brothers, Ron and Dennis, were born in 1949 and 1953, respectively. In 1961, 9 years after the 1952 invalidation of the California Alien Land Laws that prohibited my grandparents from owning land, my parents purchased a grape ranch west of Sanger California, about 10 miles east of Fresno. In 1980, they paid off the mortgage. In the aftermath of a very trying personal ordeal for both my parents, they managed to demonstrate that their personal strength, besides those exemplified by shikataganai and gaman, could get them through virtually anything. All three of us Mikuni sons graduated from college and, with our respective families, have developed lives of our own… in a United States that has shown its own strength through its recognition of, and reparation for, this mistake and woeful breach in civil rights.

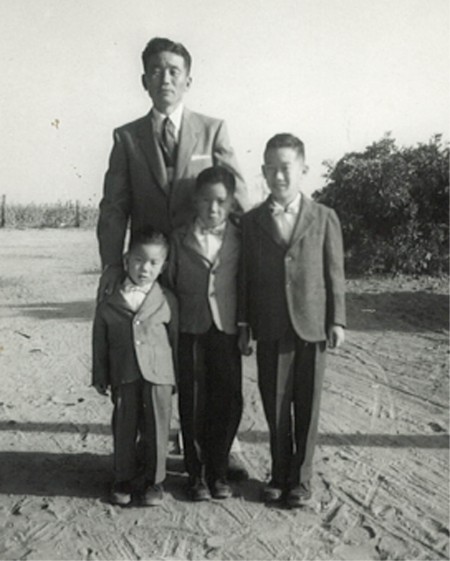

My Dad, John Mikuni, and brothers (L-to-R) Dennis (age 3), Ron (age 7), and me (age 19) at our Fresno farm. (Courtesy of Alan MIkuni)

On February 19, 1976, 34 years to-the-day after President Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066, President Gerald Ford rescinded it.

On August 10, 1988. President Ronald Reagan enacted into law the Civil Liberties Act of 1988. This law acknowledged that Japanese-Americans were unlawfully incarcerated during World War II, not as a military necessity, but based upon “race prejudice, war hysteria, and a failure of political leadership.”

On November 21, 1989, President George H.W. Bush signed the Appropriations Bill into Law that funded reparations of $20,000 plus a formal letter of apology to each of the 82,219 surviving Japanese-American detainees. John and Amy were both so recognized.

On December 22, 2003, my Dad John passed away at the age of 83. My Mom, Amy, died on September 14, 2013, at the age of 91.

The Takeuchi family still stays in touch with the Neufeld family.

Regarding the use of the term “concentration camp” in depicting this particular chapter in America’s history, comparisons to events in Europe also occurring during World War II cannot be avoided and provide perspective. The historic record and each annual remembrance of The Holocaust remind us about the atrocities perpetrated by Germany, the Third Reich, and Nazi SS in their attempt to achieve “The Final Solution.” Over six million Jewish and other peoples disfavored by the Nazis were murdered by the SS in concentration camps such as Dachau, Auschwitz-Birkenau, Treblinka, Sobibor, and the other infamous Nazi facilities in German-occupied Europe.

Japanese-Americans were also imprisoned in concentration camps, but in Topaz, Jerome, Tule Lake, and the other WRA camps in the United States. There is no parallel with respect to the extremes in how the inmates were treated by their respective captors. What is common to both the Jewish and the Japanese-American experiences is the systematic and state-sanctioned violation of human and civil rights and the use of facilities to “concentrate” the subjects of those actions. I think it is interesting to note a comment made in 1998 by American Jewish Council Executive Director David A. Harris. “We have not claimed Jewish exclusivity for the term ‘concentration camps’.” Also in 1998, Jonathan Mark, a columnist for The Jewish Week, wrote: “Can no one else speak of slavery, gas, trains, camps? It’s Jewish malpractice to monopolize pain and minimize victims.”

The US National Park Service has undertaken a program,“Preserving and Interpreting World War II Japanese American Confinement Sites” to recognize the historical significance of the ten War Relocation Authority concentration camps, as well as numerous related sites, then called, assembly, relocation, or isolation centers. In 2014, Federal funding was made available, by way of the grant approval process, to undertake projects to preserve and protect these National historic sites. Several former camp facilities are in the process of being restored, and formal designation have been granted to the Manzanar National Historic Site, and the Tule Lake Unit of the World War II Valor in the Pacific National Monument. Topaz has been nominated for National Historic Landmark designation, and the World War II Japanese-American Internment Museum, located in McGehee, Arkansas, pays tribute to those imprisoned at nearby Jerome and Rohwer.

Alan M. Mikuni

June, 2015

Click Here to Read Part 1 of ‘Camp’: Memories of Japanese Internment, 1941-45…by Alan Mikuni.

Click Here to Read Part 1 of ‘Camp’: Memories of Japanese Internment, 1941-45…by Alan Mikuni.

Alan Mikuni lives in Fremont, CA.

To read the PDF version of this article, click here and here.

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!

is there some way to contact alan mikuni? i know his brother ron and simply want to pass on a message.

[…] historical accounts, Japanese families who were interned couldn’t shop at local stores and were only allowed to order new clothes or fabric to sew their own clothes from a handful of mail-order ca…. As a result, my professor said women would find themselves all wearing very similar coats. […]

[…] historical accounts, Japanese families who were interned couldn’t shop at local stores and were only allowed to order new clothes or fabric to sew their own clothes from a handful of mail-order ca…. As a result, my professor said women would find themselves all wearing very similar coats. […]