Ned Chaffin, 86, often presages his narratives with the phrase “to make a long story short,” but his tales–many of which deal with his growing-up years in the remote sandstone jungle later preserved as the Maze District of Canyonlands National Park–are best just as he relates them, highly charged with rich, colorful details that evoke a rugged time in southern Utah history that has disappeared forever.

Chaffin spent his earliest years in Torrey, but his family, including his parents and seven surviving siblings, moved to a 2,000-acre ranch near where the San Rafael River enters the Green River in 1929, when Ned was 16 years old. The family’s patriarch, Lou, had worked at various times as a Glen Canyon miner, riverman, rancher and, briefly, before the stalwart town fathers shut him down, as a saloonkeeper in the Mormon hamlet of Loa.

Many of Chaffin’s stories have been recounted previously in the books Tales of Canyonlands Cowboys by Richard Negri and Hiking, Biking and Exploring Canyonlands National Park by Michael Kelsey. But the incidents we’re concerned with here have never been fully recounted, except perhaps around a stockman’s campfire or at one of Chaffin’s annual Green River gatherings of old-timers and young acolytes known as “cowboy caucuses.” So, at the risk of sounding hokey, sit back and imagine this tale as told in Chaffin’s friendly, open manner.

The Claflin-Emerson Expedition, 1929

In June of 1929, while Ned and his older brothers Clell and Faun were out gathering cattle and getting ready to brand calves, they pulled into one of their frequently used camps at Waterhole Flat in the Under the Ledge country. It had been raining and night was falling from the sky when their tired horses clopped into Chaffin Camp. They were surprised to discover another party already there; in that very remote country, it wasn’t common to stumble upon strangers. They dismounted and joined the four men gathered around a welcoming campfire.

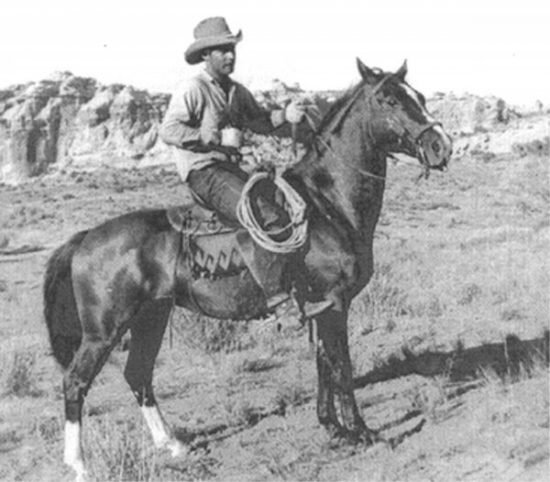

Ned and his brothers were introduced to Henry Roberts, a graduate of the University of Denver then working on his Ph.D. at Harvard University; Alfred Kidder, Jr., also a Harvard student and the son of the famous Southwestern archaeologist; and outfitter-wrangler Dave Rust, one of southern Utah’s first commercial guides who had earlier shown celebrities like Zane Grey around the Colorado Plateau. As a local guide, They had Les McDougal of Hanksville. Clustered around the fire, the strangers explained their purpose in the country: they were reconnoitering archaeological sites for a comprehensive excavation the following summer. And, as luck would have it, they were in need of a guide who knew the area.

Rust’s knowledge of the area was sketchy at best and the other two men, who had spent the previous summer digging in the Torrey area, likewise knew little about the “Under the Ledge” country. As Chaffin explained it recently, “That wasn’t country to be wandering around in during the summer without knowing where the water was.” Although he was only 16 years old, Ned knew the country intimately. His brothers were amenable to hiring him out provided the party could wait another day while the Chaffins finished branding calves.

When the three brothers returned a day later, McDougal was nowhere to be found. As soon as they discovered Roberts, who saw no need for two guides, had laid him off, the eldest brother Faun was furious. “He chewed Roberts up one side and down the other,” Ned recalls. “Goddamnit,” he said, “I never would have let you hire Ned if I’d of known you were going to fire Les. He’s a family man and he needs the dollars.” He was really mad about it…said he had half a mind to leave them down there without a guide.”

Eventually, though, cooler heads prevailed and Ned was allowed to join the Claflin-Emerson party (named for the expedition’s primary funders). “I got $1.50 a day plus a dollar for my horse when money was damned scarce in that country. Two-fifty a day,” Chaffin says. “I didn’t have any money, but I would have paid them. It was a great experience.”

Live by the sword . . .

As the party’s deadline for departure approached, Roberts wanted to visit the famous pictograph panels of Horseshoe Canyon. The party went up to the North Trail and down to the Spur where the Phillips Petroleum Company was drilling exploratory oil wells. Bob Vance, the man in charge of the operation, agreed to allow a member of his crew to chauffeur Roberts into Green River for mail and supplies. Upon their return, Chaffin discovered he’d been laid off in favor of Green River rancher Leland Tidwell, who knew Horseshoe Canyon much better than did Chaffin. “Bob Vance was furious about that. He really told ol’ Roberts off. Said he’d done all that he did just to help me. But Tidwell knew the area. And like they say, live by the sword, die by the sword…” Chaffin says, trailing off, his good humor never waning.

The digging begins, 1930

After devoting the summer of 1929 to reconnaissance work, expedition members concentrated on excavating the second year. In addition to Roberts and Rust, the group was composed of Donald Scott, Jr., son of a future curator of Harvard’s Peabody Museum; James Thurber Dennison, whose father owned a New England manufacturing plant; and Waldo Emerson Forbes, grandson of the famed author and philosopher.

“It was a great experience,” Chaffin says, his enthusiasm undiminished by the passage of decades. “I was making $3.00 a day when you could hire a top-notch cowboy for $45 a month. Some of them were working for $25 a month. I knew where most of the sites were that you could get to on horseback. Down there in summer it wasn’t a good idea to be wandering around unless you knew where the watering holes were.”

In addition to locating campsites and watering holes, Chaffin’s tasks included caring for the string of horses and mules, helping with packing, and wielding a shovel. “It was no playhouse, but we still managed to have a good time. In the evenings when the work was done, we went for hikes and sang. The camaraderie was tremendous,” he says.

They began at Sidewalk Spring, where they uncovered a buffalo robe buried under loose gravel and earth. Next, they moved onto Cottonwood Spring, where a week’s excavation yielded half a dozen corn cobs bundled together in bark, as well as a piece of red ocher that Roberts believed was used as pigment for rock art. At Cottonwood Spring, above where Clearwater Canyon begins, Chaffin left behind his signature and the date: August 17, 1930.

Speaking in 1995 with author/researcher Richard Negri, Chaffin expressed regret for his grafitti: “The reason [Dad] never wrote his name on the walls was because an old Indian medicine man who treated him for some blood poisoning had told him, and the words went something like this, ‘The man who leaves his mark on the canyon wall leaves his soul there, too.’ I know that’s the truth from personal experience. I’ve got my name on the walls down there, and if part of me isn’t down there, I’d sure as hell like to know where it is at. It always will be; there is never a day goes by that I don’t think about those canyons down there. Not one single day of my life. My dad told me, “Never write your name on these walls. Never cut your brand on the rock!” And I paid him as much attention as I did to the wind blowing, and I’m sorry. I’m sorry my name is on those walls down there.”

After finishing at Cottonwood Spring and briefly visiting the Willow Tanks, the party moved down to Horseshoe Canyon, pitching their camp at the Mouth of Spring Canyon. There, they were joined by Don Scott, Sr., as well as two University of Utah professors whose names Chaffin has since forgotten. At this point, it was mid-September and summer was winding down; Donald Scott, Jr. left to attend graduate school in California, while Dennison and Forbes returned to their studies at Harvard. Nonetheless, the digging continued for another month, until the middle of October, with only a skeleton crew. At that point, the remaining members packed up the tools and said their good-byes. By prior agreement, Chaffin drove Rust’s mules back over the rough trails to Hanksville where he was to meet the older guide and horseman. Chaffin fondly recalls his overnight stay in the small town.

“That was when Frank Webber and his wife had a little boarding house in Hanksville. I stayed there while I was waiting to meet with Mr. Rust. Mrs. Webber had a big garden out back. I’d take a salt shaker out to the tomato patch and eat three or four of those tomatoes at a time; I’ll always remember how good those tasted after three or four months Under the Ledge and eating out of a can or eating Mr. Rust’s rice and beans.”

Upon returning to his family’s ranch, Chaffin had great stories to tell. But at least in the short term, he was more excited about the check for almost $200 waiting for him. “I was one of the richest people in southeastern Utah. There really wasn’t no way to make a dollar,” he explains.

Seventy years later, Chaffin has no trouble identifying the formative effect of the two summers. “It was a different environment than I was used to. It was like being in school, being around people who were interested in education. It was stimulating. It gave me a new outlook on who had been there before, and how they lived.”

Inevitably, the exposure to the outside world increased the 17-year-old’s interest in experiencing life beyond the confines of southern Utah. But not before he spent another six years chasing cattle. “Those were lonely experiences and good times, too,” Chaffin says. The winter after he graduated from high school in Green River, Chaffin went to work herding cattle for a neighbor, spending four months by himself on the Green River at Millard Canyon.

“Oh, it was quiet,” he says solemnly. His employer had equipped the remote cabin with a radio and on one cold, still January night, Chaffin managed to pick up the broadcast of a Maryland college’s senior prom. “You could hear the girls laughing and the shuffling of the dancers and the sounds of the dancers. I’ll never forget how bad I felt that night, how lonesome I was for anybody.”

But things got worse–or at least more isolated–when the radio battery went dead in February, leaving Chaffin with no link to the outside world for more than two months. “I never saw a soul, only the wild geese that flew low over the river on a moonlit night as they migrated once the weather started warming up.”

In 1936, at the age of 23, Chaffin went to visit his older sister Gwen who was married and living in Bakersfield, California. “Her husband was a foreman and offered to help me get a job as a carpenter,” Chaffin says. “It sounded pretty good to me. All the girls I saw Under the Ledge had tails; either bushy ones like a horse or shorter ones like a cow.” At a dance he met a pretty black-haired girl named Marjorie, and the two began spending considerable time enjoying one another’s company.

But it wasn’t until six months later, when Chaffin returned to Price for his parents’ 40th wedding anniversary that he realized how smitten he was. “I stayed around the ranch and did some work for five or six weeks and I couldn’t hardly wait to get back.”

The two wed shortly after Ned returned to California, and remain married to this day. Among its other accomplishments, Claflin-Emerson is remembered for coining the term “Fremont” to describe a prehistoric American Indian culture based on hunting, gathering and agriculture. Nowhere are Ned’s contributions to the expedition mentioned in any of the official bulletins published by the Harvard Peabody Museum. But, as he might say, it was worth it: “I had a great time”.

And although he claims he left part of his soul in the Under the Ledge country, Chaffin freely admits he wasn’t tempted to return to a life of ranching. “I came here [to Bakersfield] and finally got me a steady job. That’s beautiful country and a nice place to go have a look, but back then at least, you had to hardscrabble it. If you worked hard and things went your way, you made enough to cover your taxes, but no more. It was a different world than we know today.”

Barry Scholl is the editor of Salt Lake City Magazine.

To read the PDF version of this article, click here.

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

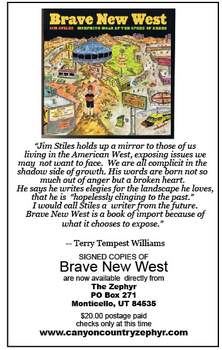

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!

Really enjoyed the read! I think I was born in the wrong time.