A two-part essay on the process of New West gentrification and the future of San Juan County, Utah after the designation of Bears Ears National Monument. Part one will provide historical context and define certain conceptual terms in order to make more explicit the major trends and forces that are transforming canyon country. Part two will more closely examine how these trends and forces are made manifest in practice and in what ways they will likely accelerate the transformation of San Juan County. Note that the class-cultural and economic dimensions of the Bears Ears controversy are my focus; I do not directly take up the political machinations leading up to monument designation (and escalating since) nor related land use or environmental questions.

Part 1: The Meaning of the Rural West in a Post-Industrial Age

Pandora’s Box

On January 28, 2016, President Barack Obama designated the Bears Ears National Monument and unleashed a whirlwind. As expected, monument opponents immediately condemned the designation and pursued its modification through both executive and legislative action. For their part, and also according to script, monument proponents countered by filing lawsuits and by launching a massive national media campaign intended to tilt public opinion in their favor.

For those who followed the process leading up to monument designation, it was depressingly predictable that the post-proclamation discourse would generate much more heat than light, especially since the designation occurred in the immediate aftermath of an exceptionally polarized national election. For the communities of San Juan County, however, the persistent manufacture of political outrage over the boundaries of both the Antiquities Act and the monument itself is largely beside-the-point. Pandora’s box was opened, the forces previously (more or less) contained therein were let loose, and closing the box now won’t change that fact. The future of San Juan County has been irrevocably altered.

The Deindustrialization of America

To begin forming a more educated guess about the future of San Juan County, it pays to first back up and zoom out, to put the new pressures on the county in a broader historical context and to define several key terms.

Like other advanced economies, America is decades into a vast shift from a predominantly industrial to a post-industrial socioeconomic order. This evolution involves both processes of production and norms of consumption, with significant impacts on employment and a broad range of social institutions. America is still the planet’s most gluttonous consumer of agricultural and industrial products, but the processes that provide these goods have been thoroughly consolidated, automated, and/or offshored. Oligopolistic agribusiness has largely supplanted the family farm and textile manufacturing has mostly been relocated to Asia, to give just two examples.

At the same time as American productive focus has shifted away from industrial sectors, so-called post-industrial sectors of the economy — broadly knowledge- and service-based occupations — are on the rise. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, between 1915 and 2015, ‘manufacturing’ declined as a percentage of all nonfarm employment from 32% to less than 9%, and ‘transportation and public utilities’ employment declined from 13% to 4%. Farm employment dropped even more precipitously over the same period, from about 1/3 of all American workers to less than 1 in 50. Meanwhile, employment in ‘other professional services’ grew from 3% to 29% of nonfarm employment, and ‘wholesale and retail trade’ grew from 13% to 23%.

These economic trends are the subject of extensive study and commentary, yet the social cost of this transformation is only rarely deeply appreciated, especially as it pertains to rural America. Certainly the numbers alone do not tell the full story, nor does the catch-all term ‘restructuring,’ which is a dry, academic label for what happens when some occupations, and the people who once filled them, are unceremoniously tossed into the dustbin of history.

Postindustrialism and New West Gentrification

The trend away from an industrial socioeconomic order is certainly manifest in San Juan County. For example, in 2016, oil extraction in the county amounted to 50% of 1986 output and natural gas about 30%. But San Juan County is different from some rural places in several important respects: it is an abundantly wild and incredibly scenic place; a large amount of its archaeological record has been well-preserved in its remote and rugged backcountry; and it lies within the popular Grand Circle region. These elements make San Juan particularly susceptible to a specific type of socioeconomic restructuring due to ‘amenity migration’:

Rural communities throughout the postindustrial world are in the midst of a significant transition, sometimes referred to as ‘rural restructuring,’ as traditional land uses, economic activities, and social arrangements transition to those associated with ‘post-productivist’ or ‘multifunctional’ landscapes. Amenity migration, the movement of people based on the draw of natural and/or cultural amenities, can be thought of as both driver and outcome of this transition, resulting in significant changes in the ownership, use, and governance of rural lands, as well as in the composition and socioeconomic dynamics of rural communities. Amenity migration is a phenomenon of increasing interest to rural geographers and other social scientists due to the ways in which, in concert with other social, economic and political processes, it is contributing to the fundamental transformation of rural communities in more developed regions throughout the world. (Citations omitted.)

— Gosnell & Abrams. Amenity migration: diverse conceptualizations of drivers, socioeconomic dimensions, and emerging challenges. GeoJournal.

One writer has described amenity migration as ‘permanent tourism’, by which he means that “rural gentrifiers are enacting cultural projects akin to those of tourists but doing so with the intention of permanently writing them into the social and physical landscape.” More specifically, amenity migration imposes an exurban, distinctly post-industrial order on a rural geography previously structured around the logic and values associated with industrial-age middle-class society. In its focus on post-productivist values like scenic aesthetics and outdoor recreation, amenity migration refers primarily not to counterculture back-to-the-land rural migrants, but to seasonal and other part-time residents and full-time modem cowboys. Note also that the amenitization of a given place is itself not a naturally occurring fact but a socially constructed process.

I will more fully unpack the tangible characteristics and implications of these phenomena in the second part of this essay, but for now it is enough to preview the argument that rural amenity migration entails many of the same generic characteristics as urban gentrification and settler colonialism. That is, generational occupants of a place come to be dominated politically and economically by new in-migrants through the latter’s control of land. Physical displacement or dispossession, either partial or complete, is also not uncommon.

Viewed in this light, it becomes clear that what is truly at stake for San Juan County post-Bears Ears is whether existing local communities will retain a meaningful degree of self-determination or be the next place to be changed wholesale by New West gentrification. In short, the battle over Bears Ears is not, primarily, a land use struggle; it is a class struggle.

Consumer Culture in the 21st Century

When deep space exploration ramps up, it will be corporations that name everything. The IBM Stellar Sphere. The Philip Morris Galaxy. Planet Starbucks.

— Jack, Fight Club

Nearly anything can be commodified — turned into an object of economic value — in large part because the process of commodification involves the intrinsic utility of the thing only as a starting point and primarily entails the thing’s ability to contain and express personal and social meaning. We have, for example, the concepts of ‘conspicuous consumption’ and ‘conspicuous leisure,’ in which Thorstein Veblen observed over 100 years ago that the wealthy of his time established their elevated personal worth and social status through displays of ostentatious, wasteful consumption not widely available to the poorer members of society. Veblen also noted that, for their part and to the extent financially possible, the middle and lower classes often engaged in ‘pecuniary emulation,’ which is the class-aspirational act of imitating the consumption and leisure practices of the wealthy.

In this way, the process of commodification is about the relationship between people as much as it is about the relationship between things. Luxury goods command a price premium compared with their substitutes not because of, or at least not merely because of, their functional superiority, but because of their positional superiority.

Processes of commodification are of course always embedded in a particular historical context. And so, as America has transitioned from an industrial to a post-industrial society, so has the range of possibilities for commodification. Whereas in Veblen’s era the ordering of class differences revolved almost entirely around material objects of higher or lower esteem — houses, art, jewelry — it is now steeped in post-productivist logic and values. Social status is now fragmented along niche tribal lines from up and down and all across the socioeconomic strata and is sometimes paradoxically expressed in terms that are oppositional to the production and consumption of material objects. As a society, we may not have become better at bridging class differences, but the market has become immeasurably better at providing consumers with the means for their expression.

Post-Luxury and the Connoisseurship of Nature

Our language — as expressed in the academy, in professional business literature, and in mainstream culture — reflects this evolution. For instance, some researchers have extended Veblen’s terminology in noting the elevated status now associated with ‘inconspicuous consumption’ and ‘conspicuous conservation.’ Increasingly, avant-garde brand strategists argue that conventional ideas about product-oriented class-signaling are entirely outdated, replaced by a New Luxury or Post-Luxury order in which metaphysical objects such as experiences and time itself have become the new frontier of commodity fetishism. And of course modern corporate marketers deftly engage such apparent non-commodities as nature and feminism to sell, for example, Jeeps (and vice versa).

New West gentrifiers — and the businesses, political parties, towns, NGOs, etc. to whom they are the target market — fully occupy a leading edge of this evolution. In the New West, relics of the industrial Old West are not just undesirable but viscerally repugnant. Oil derricks, mines, ATVs and livestock are not just stains on the landscape, but symbols of a low, coarse form of human civilization to be kept out of mind and therefore out of sight in an ugly corner of America or, better yet, offshore in a developing country. The downmarket offerings of the typical Old West main street are likewise met with disdain. Instead, the presence of such amenities as yoga studios and third wave coffee shops signify the elevated status of a place, and nature itself is made a prestige product, an Instagram-perfect stage for the performance of socially worthy expressions of affluence.

This raises something about the Bears Ears narrative that I think is intuitively grating to many people with a longstanding connection to San Juan County: marking onto a map a boundary around nearly all of the county’s off-reservation backcountry and stamping it “Bears Ears” is itself an aggressive, reductive act of commodification. The limited utility of the land along industrial and pre-industrial lines is essentially status quo ante, yet its socioeconomic meaning was completely transformed by the monument designation. A landscape that went by many names and contained overwhelming multitudes of meaning was reduced not just to a political football, but a slick media brand suitable for easy use as a status good by millions of people who had never so much as heard of San Juan County before December 28, 2016.

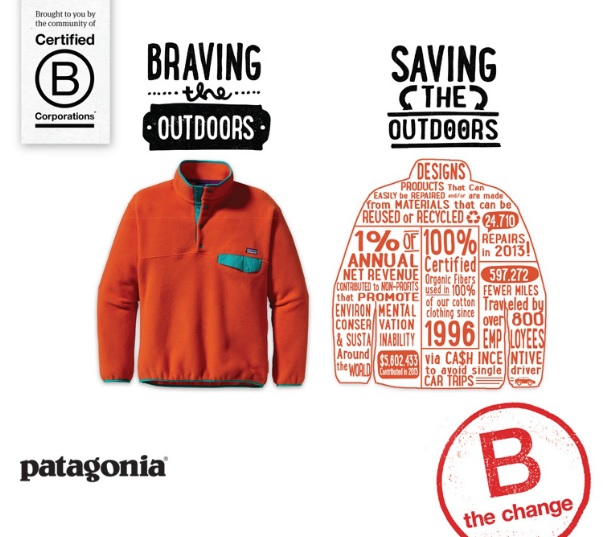

The underpinning logic, here as in most New Luxury categories, comes down to questions of connoisseurship, and, in this conceptual move, the potential for drawing hairsplitting distinctions in the service of financial profit and class hierarchy becomes nearly limitless. Perhaps the most common trope of the post-industrial connoisseur is the performance and ownership of “authenticity,” and no corporation in the New West marketspace more expertly practices this form of antimarketing than Patagonia.

Ridgeway [VP of Public Engagement for Patagonia] can sometimes sound a little weary at having to explain to outsiders a way of life that comes quite naturally to him. ‘We don’t want to hold ourselves up in some arrogant exclusivity,’ Ridgeway said, but then described the kind of customer that Patagonia does not ‘necessarily want to invite under our umbrella.’ Namely, people who want to climb Mount Everest for bragging rights – the sort of affluent adventurers, drawn to climbing in part by Patagonia, whose impact Chouinard now regrets so much. ‘Someone who has paid $100,000 for a guided climb where the sherpas put the route in and risked their lives fixing the lines and carried all your stuff up for you and positioned your oxygen balls so you could go up and come back and say you climbed Everest. That doesn’t work for us,’ Ridgeway says. ‘And we don’t mind saying it publicly.’

— Meltzer, M. Patagonia and The North Face: saving the world – one puffer jacket at a time. The Guardian.

It’s all right there: in a rhetorical move that deems superficial and vulgar even Patagonia-adjacent manifestations of outdoor enthusiasm, we have luxury branding that pretends to be transcendent of both luxury and branding. Patagonia and their fellow New West charlatans construct a particular hierarchy of authentic, enlightened outdoor connoisseurship and, as if by coincidence, those who buy into their articulation occupy the top point of the pyramid. This is how it becomes not just logical, but an act of supreme good taste and environmental consciousness, to spend $65 on a pair of running shorts fabricated from petrochemicals, stitched in a Vietnamese factory, and shipped halfway around the world to a boutique in Telluride. Or to launch, with no apparent sense of irony, an expensive, multimedia advertising and political campaign “in defense” of a landscape where the greatest objective threat of development and degradation has long been the one posed by the New West’s own social construction and commodification of nature. This is how consumerism is made virtuous and conquest is made redemptive. It is, in short, how the New West expresses its manifest destiny.

_____

Select sources & additional reading:

- Hines, J. Rural Gentrification as Permanent Tourism: The Creation of the ‘New’ West Archipelago as Postindustrial Cultural Space. Environment and Planning: Society and Space.

- White, R. ”Are You an Environmentalist or Do You Work for a Living?”: Work and Nature. Uncommon Ground: Rethinking the Human Place in Nature.

- Havrilesky, H. Delusion at the Gastropub. The Baffler.

- Currid-Halkett, E. The Sum of Small Things: A Theory of the Aspirational Class. Princeton University Press.

- Rosenblatt, D. Stuff the Professional Managerial Class Likes. Anthropological Quarterly.

- Davis, J. The Commodification of Self. The Hedgehog Review.

Thought-provoking piece, Stacy. Look forward to Part 2. I’ll throw this out there:

Although “amenity migrants” can certainly disrupt the social and cultural fabric of San Juan County, forces pushing back can be a bitch. San Juan County is a hotbed of powerful, possibly violent resistance (There’s probably a pretty good reason only one of the environmental nonprofits and recreation-oriented corporations participating in a multimillion dollar, multiyear campaign to appropriate a way of life has a physical presence in the county).

I wonder about the power of New West gentrification or its inevitability. After all, if there is a Ketchum, Idaho, or a Jackson, Wyo., or a Santa Fe, N.M., or a Telluride, Colo., or a Park City, there are hundreds of towns just as scenic scattered across the rural West and America that prove amenities colonization an exception. Jackson is an enclave, unabashed in its mockery of the rest of Wyoming.

Certain pre-conditions had to be in place in order for those towns to exist the way they do now – unique forces coming along at the right place and the right time with the wherewithal to deconstruct and construct meaning of place, not to mention reliable sources of water and power or hospitable climates or climates that could be recreated as hospitable.

Even over the short term, say the next 20 or 30 years, developers fantasizing about mega-mansion in the desert will have to factor in the consequences of climate change, if not Sagebrush rebels.

Stacy, this is your best one yet! Fascinating and too true. I must take exception with

Mr. Keshlear’s response that there are “hundreds of towns just as scenic scattered across the rural west”. Perhaps he is correct if his assertion that Kelly and Moose, Wyoming, are equally as scenic as nearby Jackson, but this is a specious comparison. And you can’t tell me that Dubois, Wyoming, is just as scenic as Jackson–it’s certainly a nice quiet pretty place, but the Teton range doesn’t loom just over its shoulder. Walking along Trail Ridge earlier this summer, friend of mine told me that what we “need” is “more national parks” and we had a similar discussion. My argument was, and remains, there may be hundreds of gorgeous canyons, but there is only one Grand Canyon, hundreds of hot springs all over the west, but only one Old Faithful, hundreds of beautiful mountain valleys but only one Yosemite valley, etc. She disagreed with me, but I still think my point is obvious. As for San Juan County, which truly possesses an aesthetic worthy of traditional National Park style-designation, enjoy it now before it turns into Moab South. When the Navajo Nation loses the jobs and revenues at the closing Navajo Power Plant, they’re going to want some way to make a living. Wait for it–wouldn’t you want to visit the “Valley Of The Gods National Park” after an invigorating visit to Monument Valley and the “Arch Canyon National Primitive Archaeological Reserve”? There’s something about Gods that attracts the hordes….

[…] I have written about before, at stake in the Bears Ears controversy is the nature and pace of rural restructuring in San Juan County. As the residents of the county continue to grapple with their predicament, it […]