(photos by the author except where noted)

Author’s Note: For more than three years , I have spent most of my keyboard time writing “informational/investigative” long form articles (some might suggest ‘long-winded’) about excruciatingly serious topics…Moab politics, San Juan County politics, sustainability in the New West, historic elections, the rise of reckless and inexcusable mainstream media manipulation, and of course, the bedeviling Bears Ears National Monument.

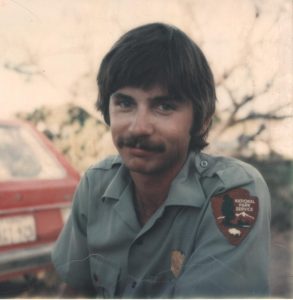

While I’m sure I’ll have more to say down the line (like it or not), I desperately need to stop for a moment, and do what I prefer…wax nostalgic about the West I discovered and loved when I first “came to the country,” almost half a century ago. After all, The Zephyr motto once proclaimed that we are “hopelessly clinging to the past.” So this is the first of a multi-part series about my decade as a seasonal ranger at Arches National Park. It was a different time and a different world. As is so often the case with all of us, I didn’t know how good I had it, until ‘it’ was gone. But to really tell the story of what it was like then, I have to go back a bit further. Bear with me, through a rather long-winded and highly sentimental introduction.

While I’m sure I’ll have more to say down the line (like it or not), I desperately need to stop for a moment, and do what I prefer…wax nostalgic about the West I discovered and loved when I first “came to the country,” almost half a century ago. After all, The Zephyr motto once proclaimed that we are “hopelessly clinging to the past.” So this is the first of a multi-part series about my decade as a seasonal ranger at Arches National Park. It was a different time and a different world. As is so often the case with all of us, I didn’t know how good I had it, until ‘it’ was gone. But to really tell the story of what it was like then, I have to go back a bit further. Bear with me, through a rather long-winded and highly sentimental introduction.

–JS

IN THE BEGINNING (AND BEFORE THAT…)

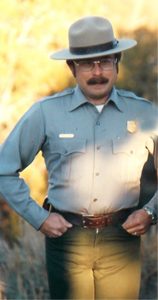

I always thought I was too short, too skinny, too shaggy, and too contrary to ever be an employee of the National Park Service. How I ended up as one is a story of dumb luck, or fate, or being in the right place at the right time–or all of that and more. My previous encounters with rangers, as I first explored the West’s national parks in the late 60s and 70s were limited. I was either seeking information on backcountry permits, or explaining to some officious ranger why I didn’t have one. Most of the time back then, the park backcountry was so quiet, a permit wasn’t required.

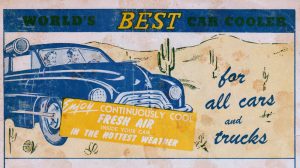

In late July 1968, my buddy Jeff Dutton and I made our first unsupervised trip out West from Kentucky. We made the 8000 mile journey in a yellow 1965 Ford Fairlane; very few cars were air conditioned then, but in the desert, a tube shaped add-on device called a Thermador Cooler was popular. It attached to the car’s passenger window and we ordered one via the JC Whitney catalog. It operated like an evaporative cooler–we filled the tank with water and the speed of the car spun a fan and pulled the water across the cooling pad— but every time we tried to use it, we got sprayed with water. We finally gave up and learned to love the dry heat.

The Interstate Highway System was under construction and only partially completed in 1968 and much of our early itinerary followed Route 66. I remember that in Arizona, the highway was especially wide–each lane must have been close to 40 feet, and broad enough for two lanes—and it was custom and tradition for slower vehicles to drift right so that faster cars could pass.

We reached the South Rim late in the afternoon. Here we were– two kids from Kentucky, on our own, standing at the edge of the Grand Canyon. We were living a dream that few of our peers even considered at the time. Our plan was to hike down the Kaibab Trail to the bottom, to Phantom Ranch. Even the idea of the Inner Gorge seemed like a remote and mysterious notion—as if we’d be entering another world.

But there was always the mundane pulling us back to Reality. There were rules. So we went to the park visitor center and asked, did we need a permit? The ranger smiled. “Just go,” he said, “…and don’t get lost.” We loaded up our canvas Boy Scout ‘Yucca Packs,” descended along the Kaibab Trail, and didn’t see another hiker. Phantom Ranch was empty. We had the Inner Gorge to ourselves.

The story was the same at Yosemite. No permit needed. We hiked 15 miles, past Vernal and Nevada Falls, and past the few hikers who’d gone that far, to Merced Lake. We arrived at dark, found the place almost deserted, stupidly left our food out on a log, pitched our little Sears tent, and fell fast asleep. The next morning we awoke to one of the most stunning views. Heaven on Earth.

But we also determined that most of our food had been eaten by black bears (including a can of baked beans!). A backcountry ranger reluctantly gave us some food, but let us know that we were right to feel stupid. I never forgot his scornful glare and adopted it myself years later.

We drove up the Pacific Coast Highway and camped near Big Sur. Nobody noticed.

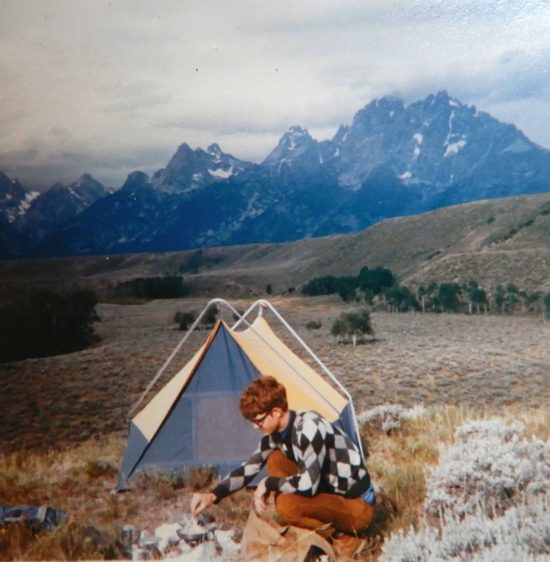

We’d brought a cheap Sears Roebuck rubber raft with us (my dad worked for Sears). Weeks later at Grand Teton, we put our flimsy little boat into the Snake River below Jackson Lake Dam and floated downstream to Moose. Late that afternoon, we stopped for the day. Jeff and I dragged all our gear up a steep embankment and camped on a bluff high above the river. We never saw a soul. Not one commercial float trip.

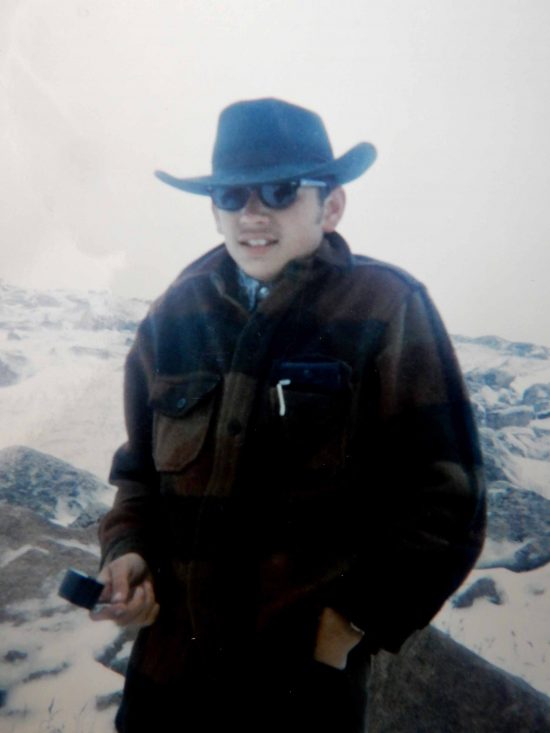

It was a time of pure bliss. Leaving Yellowstone via Beartooth Pass, we got caught in a blizzard—in August. For two Kentucky boys, the experience was exhilarating. We stopped in the snow and photographed each other for posterity…it even reveals my near-futile attempt to grow a mustache. Futile indeed.

These accounts are not meant to suggest that the national parks, in the late 60s and 70s were deserted and serene. The ‘frontcountry’ of the better known parks sometimes seemed as busy as a city, but only by the standards of the times. Yes, Grand Canyon Village could be hectic on a summer day, but I could always find a spot in the parking lot. We could always get a campsite, and the backcountry was as quiet and deserted as I am describing it. But it wouldn’t last long.

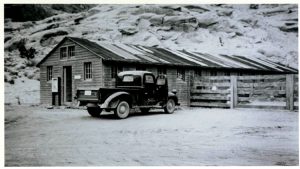

The surge in park visitation after World War II was significant; Americans, after a decade of the Great Depression and four years of global war, were ready to travel. But the condition of national park infrastructure after the war had, in most cases, changed little in decades. Most of the roads were “unimproved.” A shack served as a “visitor center,” and the toilets were often the nearest tree. For some, it was exactly the way the national parks should be. But in the wake of the war, technology and modernization were transforming the world. The parks would not be spared.

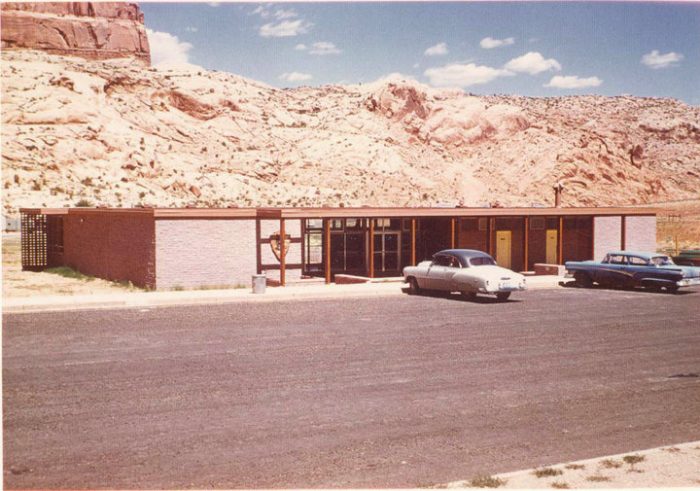

Consequently. in the 1950s, a massive “rebuilding” program, with a multi-million dollar budget enacted by the Congress, set out to modernize the parks. It was called “Mission 66” and the ten year plan, according to its architect, NPS Director Conrad Wirth, was to make the parks more accessible and more convenient–improve and add paved roads, build visitor centers, and other services for the ever-growing demands of the American tourist.

But there’s an expression, ‘Goldfish grow to the size of the bowl.’ The plan was successful beyond its creators’ wildest dreams, if sheer numbers of tourists was the standard by which to measure it. Visitation exploded. It was the beginning of what Edward Abbey would call “Industrial Tourism.”

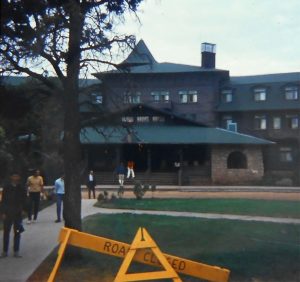

In Southeast Utah, recent ‘improvements’ had quadrupled the number of tourists entering Arches National Monument. The old entrance road was abandoned and a new 18 mile paved highway was completed to Balanced Rock in 1958. The pavement was extended to the Devils Garden by 1963, along with a new campground, complete with “comfort stations,” running water, designated campsites, a million dollar visitor center, an entrance station to collect fees, and a plethora of rules and regulations that always accompany “improvements.”

Of course, these details are all familiar to most of you Ed Abbey followers. Abbey came to Arches in 1956, spent two seasons as a ranger there, living out of a small trailer near Balanced Rock. He spent as much time as he could hiding from the tourists, or complaining about their ever increasing numbers—even then he regarded them as “hordes.” (In 1957, visitation at Arches barely reached 25,000). In “Desert Solitaire,” he confronted the engineers who were surveying the new road, utterly bewildered that anyone thought a new road was a good idea. “Clearly,” he later wrote in “Desert Solitaire,” these people were mad.”

Abbey, frustrated with the changes, left after the 1957 season, but came back for a third in 1965, after all the “improvements” he’d feared and loathed had come to pass. In fact, Abbey spent that summer in the seasonal apartments near the visitor center.

(For those of you who want to complete your Abbey Pilgrimage, it’s apartment 7A…but don’t even ask where his trailer was.)

By the mid-70s, a quarter of a million tourists were making their way to Arches. In 1972, Congress upgraded the monument’s status, as well as its roads and it became Arches National Park. (It’s a little known fact that when the park was created, its size shrank by more than 10,000 acres.)

* * *

To this American West, well past the cusp of being “discovered,” but not quite at the point of being stampeded, I loaded up my VW camper bus, and my dog, and $900 in cash, and and set out in search of a home. My target was southeast Utah. Four years earlier, I’d experienced my own “This is the place” moment, when I took a wrong turn on a dirt road, just south of Blanding and a few miles later, found myself staring into the most remarkable landscape I’d ever seen. The view of Comb Ridge and Cedar Mesa from the top of the old dugway. That image is still burned into my brain, almost 50 years later. (see Hadley Rill story). I knew I belonged here. For the next 24 hours, as I made my way across southeast Utah on the old dirt version of Utah Highway 95, I saw no one. It was my “undiscovered country.” I knew I’d be back.

I was right, and in fact, it’s all I thought about. For years, while I suffered the hardships of unfulfilling jobs and a landscape too green for my desert obsession, I even refused to acknowledge where I was. Or when at least. To the bewilderment of most and the amusement of some, throughout those years, I always kept my watch set to Mountain Time. In my heart and soul, that’s where I already lived. It’s what sustained me through every hard moment, every crisis, every failure. I sometimes wonder what I would have done without the dream of the West to carry me along.

I saved my money, and each time I had enough to travel, I quit my job and went West. I planned itineraries to places I knew nothing about. I buried myself in maps and atlases. Sometimes I’d randomly pick a spot on one of my topo maps and make that my destination.

After my first trip West with Dutton, I went back to the Grand Canyon the next year. And the next. I hiked to the river again and the following year I started exploring the “primitive” trails–the Grandview Trail and the Hermit Trail, to name two. The ruins of the old “Last Chance” mining camp below the rim on Horseshoe Mesa were still intact.

After my first trip West with Dutton, I went back to the Grand Canyon the next year. And the next. I hiked to the river again and the following year I started exploring the “primitive” trails–the Grandview Trail and the Hermit Trail, to name two. The ruins of the old “Last Chance” mining camp below the rim on Horseshoe Mesa were still intact.

But in 1973, on a visit to the Bright Angel Lodge gift shop, I spotted a small booklet that turned me pale and weak. Its title: “A Guide to the Primitive Trails of the Grand Canyon.” Nobody even knew these trails existed a couple years earlier. Now, almost overnight, trail use exploded. The NPS imposed a reservation system. The main trails were booked a year ahead. And even the Hermit Trail had a waiting list. The beginning of the end had begun.

I passed through Moab for the first time in January 1973, in the dead of what many old Moabites call the “coldest winter.” Months earlier, I’d bought a Volkswagen without a heater and I resorted to burning cans of Sterno on the floor of the car to keep warm. Flames were leaping between my legs as I pushed east to Grand Junction.

I came back the following summer and visited Arches for the first time. I even camped in a designated campsite for a few days, but I learned how to dodge rangers and the camping fees they were always hounding us for. Two bucks a night was way beyond my budget at the time and at Arches National Park, I learned just when to be away from my camp site, and when to return. Years later, the irony would not be lost on me.

The following year, late in October 1974, I stayed at Arches again. The “tourist season” was over by then, and the campground water and lights had been turned off. I had the place to myself. And it was free. My dog Muckluk and I explored the far corners of the Devils Garden and returned each afternoon, exhausted and exhilarated. But eventually, I’d always find my way back to my comfort zone in Kentucky.

I knew I had to go for good. In July 1975, I finally assembled the necessary funds, a reliable vehicle, my semi-reliable Muckluk, my dog-eared copy of Abbey’s ‘Desert Solitaire,’ and most of all, the courage and the will to go West permanently and start the life I believed I was meant to lead. I had no idea what kind of life it might be. But I was young and stupid and threw caution to the wind. I went West

* * *

At first I was just doing the things and going to places I wanted to see. Gainful employment kept skipping my mind. I drove down an old road south of St. George (which then had a population of 12,000) in search of “Wolf Hole, Arizona” and that lying bastard Ed Abbey. He took great and perverse pleasure in misleading his legions of fans by giving that remote location as ‘home.’

(Weeks later, when I found him in, of all places, Moab, I told him of my Wolf Hole experience. He grinned and said, “Ah yes. Wolf Hole. Never been there…what’s it like?”)

I spent a month alone on the North Rim, thirty miles west of the park highway, at the end of an old dirt two-track fire road. I saw nobody. While I was perched on the edge of the world, I learned that President Ford had been shot at twice and they’d finally caught up with Patty Hearst. I had no idea.

Muck and I explored the rim for miles, wandered off trail into the canyon, watched extraordinary dawns and dusks. Smoked cheap cigars. Drank lots of coffee. Ate many Bisquick drop biscuits. It was glorious. When I drove out to Fire Point, it was late summer; when I came back to civilization, autumn was in full swing. ‘When did the aspens turn?’ I wondered. There was a chill I hadn’t felt along the rim.

I’d been enjoying myself for sure, but four months later, I was starting to get worried. Winter was coming and my funds were running low.

I’d been enjoying myself for sure, but four months later, I was starting to get worried. Winter was coming and my funds were running low.

Coming off the North Rim in a blizzard, I almost found a job as a teacher’s aid in Kanab (another story for another time. Remind me to tell my Alex Joseph story). But I’d also heard they were making a Clint Eastwood movie nearby (it turned out to be “The Outlaw Josie Wales”) and I drove to the Wahweap Hotel for an audition as one of the “redlegs.” extras. But the casting director took one glance at me, concluded I looked a tad young (like 12?) and too scrawny to be a badass outlaw.

Slowly I made my way back to southeast Utah. I listened to the sixth game of the classic Boston/Cincinnati World Series–the Carlton Fisk home run in the bottom of the 12th–huddled in my bus just outside Capitol Reef in another snowstorm.

The next day, I got as far as Comb Wash. I parked in the cottonwood trees and that night the temperature plunged into the 20s. My ’65 VW ran on, if you can believe this, a six volt battery, and the next morning, covered in frost and falling leaves, she groaned and sputtered and…barely started. I could see myself stranded there for weeks…months…years. Oh well, I thought…this is a good place to die.

Or maybe not. I was too young not to consider my other options, so as the motor warmed up, I decided to head for Natural Bridges. At least the visitor center would have some heat. It was a 35 mile drive, all up hill and the old bus labored mightily to make the climb up the east ramparts of Cedar Mesa.. We peaked out at Salvation Knoll and pushed onward along the still unpaved Highway 95. Finally, on the morning of October 24, 1975 I reached the Bridges visitor center. There were no cars in the parking lot. The place was empty except for one lone ranger sitting in the small office behind the front desk.

I looked like a refugee from a Poor Man’s Hell. I was dirty, and half frozen, and a tad grumpy too. A large glass window separated the ranger’s office from the public side of the interpretive exhibits. In those days and at that time of year, rangers actually looked forward to a little company, even from tourists. So the ranger came out from the office and to say hello.

I looked like a refugee from a Poor Man’s Hell. I was dirty, and half frozen, and a tad grumpy too. A large glass window separated the ranger’s office from the public side of the interpretive exhibits. In those days and at that time of year, rangers actually looked forward to a little company, even from tourists. So the ranger came out from the office and to say hello.

I returned his greeting but before I could even begin to give him my sad tale, he looked me over, shook his head and chuckled. Ranger Dave Evans said, “Pardner…you look like you could use a cup of coffee.”

He was right. And that was the moment when my life changed.

NEXT TIME: Becoming a ranger at three dollars a day.

Jim Stiles is Founder and Co-Publisher of the Canyon Country Zephyr.

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

Loved this article and look forward to the next!

What a Fun read! Ready for Part 2.

Enjoyed it, Jim.

A lovely Christmas morning sipping coffee, munching my sister’s biscotti, and reading this article. I raise my cup to toast the old Volkswagen van days. We may have been the last humans to have the opportunity to truly be wild and free. And our dogs were fortunate too.

What a wonderful story! I’m a Louisville, KY native and had a fabulous 6th grade teacher named Mrs. Sue Stiles. Is there any chance that she was your Mother? I became reacquainted with her at St. Paul church in Louisville. I corresponded with her a little bit when she moved to Lexington. I’m wondering what happened to her.

Even if there is no connection, I will be back to read more.

Hey, Jim, LOVELY tale. Now that I am retired I am hoping to take a driving trip soon to revisit Arches along with other favorite my west locations AND DO VIDEO AGAIN there!!