Note: An updated and expanded version of this article will appear in the Dec/Jan Zephyr.

Prologue: Some of this information may be familiar, to you who take the time to read my long-winded articles. But I’m trying to consolidate facts and put them into a more concise narrative. Thanks for enduring my redundant tendencies. Also note this is strictly an examination of the monument proposal, and the impacts a monolithic recreation industry may have upon it. This is not an endorsement of Rep Bishop’s Public Lands Initiative…JS

I’m not a native-born Utahn, nor a Native American and I’m not a Mormon. I came to southeast Utah almost 40 years ago and made it my home. One of my first and most enduring views of this most cherished land was the Bears Ears. They are as sacred to me as any church. It would stand to reason that I’d also be a supporter of the proposed national monument. But I have concerns that monument designation may not just fail to provide the protections some want; it may create impacts some proponents can’t or won’t imagine.

The Bears Ears Monument debate and efforts to protect potential wilderness in southeast Utah is not new; its roots go back decades. The history of the West’s fight over “public lands” reaches back much farther. Centuries, in fact.

“PUBLIC LANDS”…IN THE BEGINNING

Millions of Native Americans inhabited the width and breadth of this continent for thousands of years before White Americans came to claim it for their own. Great societies flourished from coast to coast, but in the span of two centuries, white “progress” decimated and destroyed these populations, if not their cultures. Relegated mostly to reservations, Native Americans played little if any role in the eventual public lands debate. With the “Indian Problem” shamefully resolved, America’s politicians moved to regulate, distribute and administer the vast acreage of The West.

Today, many Americans believe that “public lands” were set aside specifically by the federal government for the multiple use and enjoyment of all Americans. In fact, most public land remaining in the West was once called the “land nobody wanted.” More specifically, the Homestead Act of 1862 allowed for the eventual settlement and development of more than 270 million acres of public land, most of it west of the Mississippi River, to more than 1.6 million homesteaders.

But there were stipulations; in exchange for the acquisition of 160 acres of land, the settlers had to occupy that land and farm it for five years. It had to be productive. But especially in the parched desert southwest, it was almost impossible to make a living on a piece of ground that small and dry. Subsequently, much of those lands–millions of acres— became “public domain.” Trying to use that land became a bloody free-for-all.

Range wars ensued, unregulated lands were badly overgrazed and abused. The land was wide-open to whoever wielded the most power, and it wasn’t until 1934 that the Taylor Grazing Act implemented any kind of controls or regulations. Surprisingly, in southeast Utah, most local ranchers welcomed the new law. Previously, they had unsuccessfully competed against the big cattle companies that moved into the area from Colorado. The Taylor Act gave the locals a leg up.

Throughout most of the 20th Century, southeast Utah and much of the Rural West was simply left alone. Ranchers grazed their cattle, families eked out a living. Many were good stewards of the land; some were not. Time and the sheer sparsity of humans spared much but not all environmental impacts. Prospectors came and went. Mines, big and small, went boom and bust.

While a few made fortunes, most of the rural settlers did not. They may have come for riches but most stayed for other reasons. In Utah, of course, the far country was settled by Mormons. For many of them, they discovered that a remote and simple life suited them. They are the outliers, the people who shun the crowds and the frenzy of “modern society,” (no matter what century), who seek life and refuge out on the far edges of the world–in the places that nobody else ever wanted.

In rural Utah,as in other remote parts of the American West, these people found a home and a lifestyle that suited them, in a place that most of us rejected as ‘uninhabitable.’ But for the outliers, it was perfect. More than anything else, and ironically like the Native Americans that were driven out before them, they simply wanted to be left alone. Like Charles Bukowski, most outliers “don’t hate people; they just feel better when they’re not around.”

Post-World War II America changed everything. Americans moved West in stunning numbers. In 1946, President Truman created the Bureau of Land Management (BLM). Its mission was “to sustain the health, diversity, and productivity of the public lands for the use and enjoyment of present and future generations.”

Demand for natural resources exploded as the economy of the United States experienced decades of unbridled, almost exponential growth. That growth created serious environmental impacts on those mostly unregulated public lands and in the 1960s and 1970s, the U.S. Congress took steps to protect them. The 1964 Wilderness Act identified lands “where the earth and its community of life are untrammeled by man, where man himself is a visitor who does not remain.”

THEN CAME ‘FLPMA.’

In 1970, Congress passed the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA). It was the first time the government was mandated to consider environmental issues in the administration of public lands and “required federal agencies to integrate environmental values into their decision making processes by considering the environmental impacts of their proposed actions and reasonable alternatives to those actions.” Thus, the birth of the “environmental impact statement.”

In 1970, Congress passed the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA). It was the first time the government was mandated to consider environmental issues in the administration of public lands and “required federal agencies to integrate environmental values into their decision making processes by considering the environmental impacts of their proposed actions and reasonable alternatives to those actions.” Thus, the birth of the “environmental impact statement.”

And in 1976, the Federal Land Policy and Management Act (FLPMA) was enacted. It “governs the way in which the public lands administered by the Bureau of Land Management are managed.”

in which the public lands administered by the Bureau of Land Management are managed.”

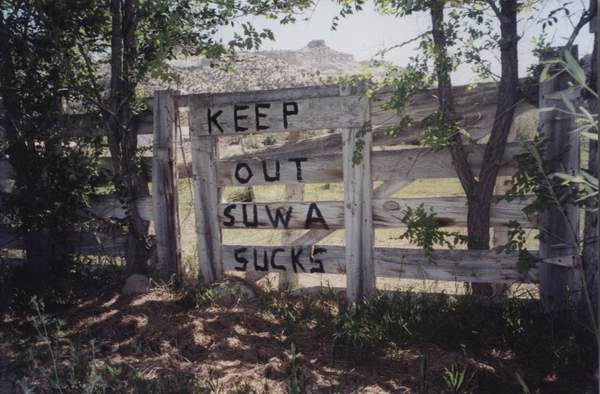

For Rural Westerners, and in southeast Utah, nothing was ever the same.

For a century these outliers had resided on lands once called, “worthless for anything except in general holding the world together.” Nobody wanted this godforsaken “wasteland;” those who tried to live there did so at their own peril and at the bemusement of almost everyone else, who thought they were crazy.

* * *

I arrived in Utah in the late 1970s, just as tempers between the ‘locals’ and the ‘feds’ were flaring. The changes in the way public lands were administered came fast and furious. With the help of these new laws, efforts to put limits on extraction and demands for more stringent rules to reduce their environmental impacts accelerated and were all part of the ‘green’ strategy to protect the natural resources of the West.

The response from ‘Old Westerners’ was angry and prolonged. After a century living and working, and relatively ignored, in one of the most remote corners of the country, its generational inhabitants were told they had to change. I still remember July 4, 1980. when Grand County Commissioner Ray Tibbetts drove a D-9 bulldozer over the “Road Closed” sign and entered the recently closed Negro Bill Canyon road, in defiance of federal law. He was backed up by more than a thousand Moab citizens. At the time, I was new to the country, a fire-breathing enviro with a copy of ‘Desert Solitaire’ under my arm; I really didn’t get what the fuss was about.

That was 36 years ago; since then the conflict has only become more intense.

THE BIRTH OF THE ‘AMENITIES/RECREATION INDUSTRY…

THE CLEAN ALTERNATIVE.‘

Being an environmentalist in the 70s and 80s was a pretty black and white proposition. Energy extraction was bad. Ranching was bad. Stopping them was good. But among the professional environmentalists, the argument was—if they hoped to eliminate or shrink the natural resource economy, they had to replace it with something else. As the energy boom began to wane, many environmentalists turned to recreation and tourism–the “amenities economy”–to replace them, as a panacea for the economic woes of the Rural West.

And as tourism and recreation became ever more significant components of the economy, investors looked for good deals—for steals—and there were plenty of them. Properties in mining towns across the West could be bought for pennies on the dollar. Land was cheap. Buildings, once full of life and energy, lay abandoned and deteriorating.

Only the hangers-on, that stridently independent handful of survivors who had preferred to eke out a marginal existence in exchange for solitude and quiet, stood in the way. Even some of them saw the economic opportunities and profited. The rest were easily pushed aside.

And so change came, and rapidly…to places like Park City, Utah and Telluride, Colorado. And Aspen. And Central City. And Salida. And Flagstaff, Arizona. And Prescott. And Virginia City, Nevada. And Durango, Colorado. And Boise and Coeur d’alene, Idaho and Bozeman and Missoula, Montana.

And to Moab, once the ‘Uranium Capitol of the World.’

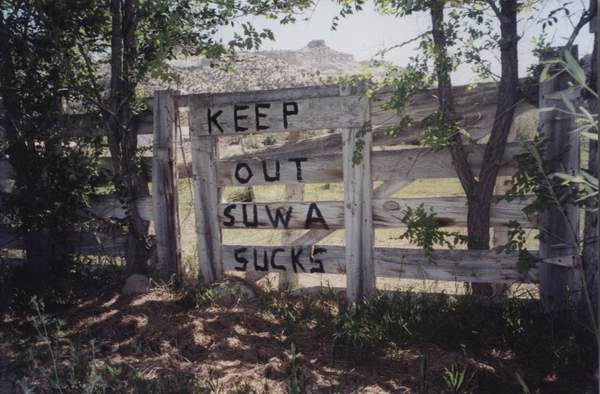

But tourism had its downside too, even in the minds of those same environmentalists seeking to put the oil and gas people out of business. As recreation exploded across the Rural West in the 1990s, groups like SUWA and the Grand Canyon Trust (GCT) warned of unbridled tourism and the impacts it could cause.

In 1998, Bill Hedden, now executive director of the GCT warned, “Everywhere we looked, natural resource professionals agreed that industrial-strength recreation holds more potential to disrupt natural processes on a broad scale than just about anything else. It’s a very tough problem affecting all of us.”

Scott Groene, now executive director of SUWA agreed, “People are drawn here by advertising, guidebooks, and publicity created through travel films, newspaper features, outdoor magazines and the like. And because of the large numbers of people being drawn to the Moab area, frequently, and  justifiably, federal land managers now lament the damage being done by too many recreationists. Recreation is like any other public land use: too much in the wrong place can be bad.”

justifiably, federal land managers now lament the damage being done by too many recreationists. Recreation is like any other public land use: too much in the wrong place can be bad.”

Groene even denounced ‘Outside Magazine’ and complained, “I quit buying Outside magazine a long time ago, when it transformed into little more than a plug for the over-consumption of expensive and unnecessary gear and silly “gonzo” activities.”

The staff at SUWA spoke out against guidebooks; the Salt Lake Tribune reported that, “the Southern Utah Wilderness Alliance will not endorse any guidebook.” And Groene explained, “…Given our goals of trying to protect the land, we felt we had to adopt this policy to be consistent in our position.”

THEN CAME THE MARKETING OF WILDERNESS

But environmentalists abandoned the moral high ground in the late 90s and made the recreation/tourist economy the centerpiece of their wilderness strategy. At a “Wilderness Mentoring Conference” in 1998, activists there declared, “Car companies and makers of sports drinks use wilderness to sell their products. We have to market wilderness as a product people want to have.” Concurrently, groups in Utah began to receive massive infusions of cash from some of the biggest venture capitalists, industrialists, and financiers in America. In return, many of those mega-wealthy donors were rewarded with seats on their boards of directors. Boards set policy.

Consequently, mainstream environmentalists in Utah found themselves awkwardly aligned with the very industry that Hedden had once warned possessed “more potential to disrupt natural processes on a broad scale than just about anything else.” SUWA’s board, with billionaire Hansjorg Wyss as its chair, repudiated the “no guidebooks” policy initiated by its staff.

And so, since the early 2000s, environmental organizations have been shockingly silent about the damage and destruction being created by the recreation industry. Anyone who’s been to Moab lately knows what unbridled tourism and recreation can do to a community and to the lands that surround it. Moab has become the poster child for every small rural community in the West, and with the same slogan…

“We don’t want to become the next Moab.”

And that’s what many citizens of San Juan County, Native American and White, fear most. The proposed 1.9 million acre “Bears Ears National Monument” could have that precise effect.

THE BEARS EARS BACK STORY

Efforts by mainstream environmental groups like SUWA and the GCT to designate wilderness in Utah has become a generational effort. Since the early 80s, proposed wilderness acreage by environmentalists have grown—from 5.4 to 5.7 to 8.3 to 8.8 to 9.1 to 9.5 million acres. Some even suggest the number is in excess of 9.8 million…nobody, neither pro- nor anti- wilderness advocates, seems sure of an exact number.

But after a quarter century, the Red Rock Wilderness Bill is no closer to passage than it was a decade ago. After enduring the hard years of the Bush Administration, greens hoped, in 2008, that their lonely years in exile were over.

But after a quarter century, the Red Rock Wilderness Bill is no closer to passage than it was a decade ago. After enduring the hard years of the Bush Administration, greens hoped, in 2008, that their lonely years in exile were over.

On the day after Barack Obama’s election, SUWA’s Groene wrote, “The new Obama administration and Congress will give us an unprecedented opportunity to protect the redrock country…Yes, we still must work hard to reverse the awful legacy of the Bush administration. But after eight long, hard years, we are about to face perhaps the best opportunity for wilderness protection in SUWA’s 25-year history.”

But the celebrations were short-lived and hardly anything went as planned. For Redrock Wilderness advocates, Obama’s new Interior Secretary Ken Salazar was a particular disappointment. In 2010,

Ken Salazar.

when Salazar came to Utah to talk wilderness, he made his views clear. He told a packed room of Utah citizens–dominated by SUWA supporters— that he favored a “from the ground up” process that supported local participation and opposed federal designation. Specifically, Salazar insisted the Obama Administration had no intention of creating national monuments on public lands and side-stepping the legislative wilderness process, an idea pushed by SUWA.

“That’s not going to happen,” Salazar said. “That would be the wrong way to go.” Instead he proposed working with locally elected officials to find consensus on wilderness

In 2012, Utah greens tried a different tactic. They proposed a 1.4 million acre “Greater Canyonlands National Monument (GCNM).” As reported in High Country News, “this expansion (or “completion” of the Canyonlands park as it was originally envisioned) would put the kibosh on conventional oil and gas drilling, and on some lesser-known extractive interests that have been sniffing around the area. Those include uranium mining, potash mining and tar sands development—uses which fragment habitats and adversely affect air and water quality.”

The Inter-Tribal Coalition

But GCNM went nowhere. By 2014, “Greater Canyonlands” faded away and soon references to an even larger, 1.9 million acre “Bears Ears NM” took its place. This time, the monument was proposed by an alliance of Native American tribes in the Southwest. Their Pro-Monument web site explains that, “In July of 2015, leaders from five Tribes founded the Bears Ears Inter-Tribal Coalition, representing a historic consortium of sovereign tribal nations united in the effort to conserve the Bears Ears cultural landscape.”

Of all the “interested parties” in the monument debate, none has a better right to be heard or a voice to be acknowledged than Native Americans, especially those most directly affected by monument designation. But controversy continues to swirl around the proposal and its origins. Gavin Noyes, the executive director of the Salt lake City based, non-profit Utah Dine’ Bikeyah, told the Deseret News, “None of the drivers of this are coming from the environmental community. It is purely Native American led. This is a Native American led effort. Any suggestion otherwise is not true.”

Terry Tempest Williams.

But is it really accurate for mainstream green groups like SUWA and the GCT to insist they had no part in the proposal? A remarkably candid and revealing letter from noted author (and SUWA board member) Terry Tempest Williams to Interior Secretary Sally Jewell appears in her latest book, “The Hour of Land.” The letter itself was written in December 2014. In her plea to Jewell (“Dearest Sally”), she describes the momentous gathering of friends at her home in Castle Valley, Utah, when the monument proposal took form.

She invited a Navajo-Dine spiritual leader from Monument Valley to discuss the monument idea. As Williams describes the meeting, “Jonah Yellowman sat at the head of the table. To his right was Scott Groene from the Southern Utah Wilderness Alliance, to his left was Bill Hedden from the Grand Canyon Trust.” Other guests around the table included Gavin Noyes from Dine Bikeyah, former Canyonlands NP superintendent Walt Dabney, Josh Ewing from Friends of Cedar Mesa, Sue Bellagamba of the Nature Conservancy, and Terry and her husband Brooke.

Jonah Yellowman explained the importance of the lands they all sought to protect. he said, “These lands are our medicine cabinets. We know that where the fog falls on a particular mesa is where one plant will be found to cure a cold, we know where each her is located that will heal us in very particular ways…This is where our wood comes from to heat our homes. Who will we become if we lose these lands?”

Groene suggested extending the monument boundary north to Canyonlands National park. Jonah agreed, “The more land the better.” Williams called the moment “transformative” in her letter and urged Secretary Jewell to appreciate the magnitude of the moment.

Sally Jewell.

But then Williams addressed her most urgent concern to Jewell. She wrote, “To then have them leave knowing the United States Secretary of Interior counseled them not to work with the Southern Utah Wilderness Alliance, was more than disheartening, it was an unexpected fracture line being drawn in the sand by Washington. The Navajo leadership returned home with a perceived directive from the Department of the Interior to disengage from a local, collaborative vision.”

Williams conceded, “People within the environmental community in Washington write off Utah as an impossibility and too often see SUWA as an impediment rather than an advocate for protecting America’s red rock wilderness. I would argue that if we can come together in Utah, and we are, we can come together anywhere.”

It was a remarkable admission by SUWA board member Williams to make. She was, in essence, conceding that without Native American participation, the prospect of a national monument designation was practically nil.

A recent Deseret News story by Amy Joi O-Donohue substantiates Williams’ acknowledgement that Native American participation was an essential part of the political process in environmentalists’ years-long pursuit of monument status. Titled “Big Money, Environmentalists, and the Bears Ears Story,” O’Donohue reported that,

“In October 2014, a group of people sat around a table and discussed their campaign to bring a monument designation to southeast Utah for the region they called Bears Ears.

“This wasn’t a group of Native American tribal leaders from the Four Corners, but board members from an increasingly successful conservation organization (The Conservation Lands Foundation–CLF) who met in San Francisco to discuss, among other things, if it was wise to ‘hitch our success to the Navajo.'”

O’Donohue noted that, “… the campaign is fueled in part with $20 million in donations from two key philanthropic foundations headquartered in California — the Hewlett and Packard foundations — that cite environmental protections as a key focus for the grants they award” It has also been reported that the Leonardo DiCaprio Foundation has recently contributed $15.6 million in grants for environmental causes, including Utah Dine’ Bikeyah and its Bears Ears Monument campaign.

One of Utah Dine’ Bikeyah’s co-chairs, Regina Lopez-Whiteskunk, told The Deseret News that linking their cause in a negative way to these grants was “insulting,” and insisted those organizations “serve a good purpose.”

But according to The Deseret News, “In the (CLF) board meeting, Norton questioned if the group was ‘hitching our success to the Navajo and if so what would happen if we separate from them or disagree with them. Without the support of the Navajo Nation, the White House probably would not act; currently we are relying on the success of our Navajo partners,’ the minutes read.”

THE CLAIMED NECESSITY FOR MONUMENT DESIGNATION

Still, pro-monument Native Americans and mainstream environmental organizations insist the Bears Ears region is under immediate and extreme threat. The National Trust for Historic Preservation calls it “one of the eleven most endangered historic places” in the United States.

The Archaeology

Foremost, proponents insist that monument designation will provide increased protection against vandalism and theft of precious archaeological resources in the area. But it’s important to understand the specific laws that Congress has passed in the last century to address those concerns.

The Antiquities Act of 1906 authorized the President to proclaim “historic landmarks, historic and prehistoric structures, and other objects of historic or scientific interest” as national monuments.

But more than half a century later, many felt the Antiquities Act didn’t go far enough. Consequently, the 1979 Archaeological Resources Protection Act was enacted “to protect irreplaceable archaeological resources and sites on federal, public, and Indian lands.” ARPA applies to all federal land, including every acre that lies within the boundaries of the proposed monument; yet monument supporters turn to the century-old law, the Antiquities Act, as a better way to protect archaeological resources than the beefed up ARPA, that was enacted to provide better protection and more severe penalties for cultural resources degradations..

What monument status could provide is more funding for more enforcement, and more restrictions on public lands, like road closures and even the designation of ‘closed areas.’ as determined by the superintendent. But federal land managers have noted that increased funding is generally linked to dramatically increased visitation.

Energy Development

Other threats to the region have included the imminent threat of massive energy development. Some monument proponents at the Bears Ears hearing in Bluff last July even spoke of “oil rigs literally between the Bears Ears.”

It’s true there are already thousands of active oil wells in San Juan County, though with the current world-wide oil glut, many wells have shut down. But oil and gas potential is not distributed evenly across the county. The overwhelming number of producing wells are found in the Aneth Oil fields at the far southeast edge of Utah and in Lisbon Valley, where energy production has been ongoing for almost 70 years.

Several years ago, the Bureau of Land Management planning office prepared a document called a “Reasonably Foreseeable Development Scenario for Oil and Gas” in the Monticello, Utah area. The survey included 4.8 million acres of federally managed lands in San Juan County, Utah. According to the BLM study: “Paradox Fold and Fault Belt, and the area of concentrated oil and gas fields in the southeastern portion of the MtPA, within the Blanding sub-basin region of the Paradox Basin, both have a high development potential.”

But much of the proposed monument overlays what’s called ‘The Monument Upwarp.’ According to the study, “development potential for the Monument Upwarp is considered moderate to low.”

There are additional small areas where energy development could be exploited–a now closed 40 acre uranium mine, the possibility of potash development at the far north end of the proposed monument..But does it require the designation of almost 2 million acres to deal with these alleged impacts? Or is it overkill? Is there another way to find resolution?

The Still Unmentionable Threat—Industrial-Strength Recreation

While environmentalists have spent millions in media campaign addressing environmental impacts, few if any have dared to confront the threat the Grand Canyon Trust once called the industry that “holds more potential to disrupt natural processes on a broad scale than just about anything else….”

“Industrial strength recreation.”

As noted earlier in this narrative, it was once high on environmentalists’ list of threats to wilderness, but abandoned 15 years ago in the pursuit of alliances with the recreation industry. On a personal note, this writer pleaded with SUWA in the early 2000s to address the threats of the recreation industry. I received this response by email from Terry Tempest Williams. She wrote, “This problem of recreation and wildness, wilderness, has escalated to the point where they/we (environmentalists) have to look at it.”

But nothing happened. More than a decade later, even the extreme recreation nightmare that now defines Moab, Utah fails to raise the ire or even comment from the mainstream Utah environmental community. Last year, when Arches National Park was literally closed–forced to shut down its entrance station due to overwhelming crowds–green groups failed to notice.

But nothing happened. More than a decade later, even the extreme recreation nightmare that now defines Moab, Utah fails to raise the ire or even comment from the mainstream Utah environmental community. Last year, when Arches National Park was literally closed–forced to shut down its entrance station due to overwhelming crowds–green groups failed to notice.

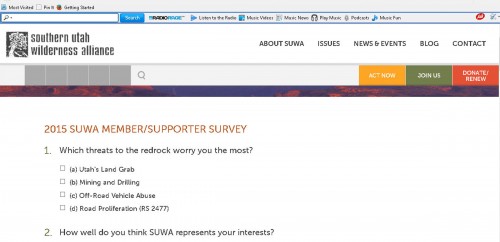

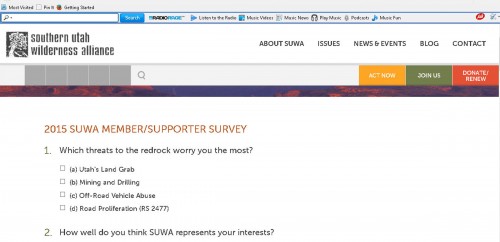

In fact, it appears they don’t believe a problem exists at all. In a recent “2015 Members/Supporters Survey,” the Southern Utah Wilderness Alliance, Utah’s flagship environmental organization, wrote to its members, “Your support and advocacy is crucial to our success in protecting the redrock, so please take a few minutes to give us your feedback.” The first question defined the scope of the group’s concerns when it asked:

“Which threats to the Red Rock worry you the most?”

Participants were given four options:

a) Utah’s Land Grab

b) Mining & Drilling

c) Off Road vehicle Abuse

d) Road Proliferation (RS 2477)

Those were the only options made available to the participants. While “Off Road Vehicle Abuse” is a valid concern that represents a part of the recreation and tourism industry, it in no way includes the vast, even startling impacts that we are witnessing across the West. What happened last summer— staggering crowds and out of control recreation, in park after park, on public lands across the magnificent canyon country, from Moab to St. George—did not warrant even a single line of “worry” from the SUWA architects who devised the survey. For them, it just wasn’t an issue.

And yet the impacts of tourism and recreation cannot be understated. Even the United Nations weighs in on the impacts of tourism on climate change.

“In 2005,” am UN report states, “ tourism’s contribution to global warming was estimated to contribute between 5% and 14% to the overall warming caused by human emissions of greenhouse.” More specifically, the UN noted, “By 2035, tourism’s contribution to climate change may have grown  considerably..The development of emissions from tourism and their contribution to global warming is thus in stark contrast to the international community’s climate change mitigation goals for the coming decades.”

considerably..The development of emissions from tourism and their contribution to global warming is thus in stark contrast to the international community’s climate change mitigation goals for the coming decades.”

And just recently, Yvon Chounard, the founder of the outdoor equipment company Patagonia and revered as the man who forged today’s strong alliance between the recreation industry and mainstream environmentalism, surprised his allies with some doomsday predictions about the recreation culture he helped invent.

In a stunning article for September 19 issue of The New Yorker, writer Nick Paumgarten’s profile with Chouinard includes this remarkable concession. Paumgarten writes:

Chouinard.

‘When I ventured to mention how the catalogue sometimes irked me, he was quiet for a while, and then said, “When you see the guides on the Bighorn, they’re all out of central casting. Beard, bill cap, Buff around the neck, dog in the bow. Oh, my God, it’s so predictable. That’s what magazines like Outside are promoting. Everyone doing this ‘outdoor life style’ thing. It’s the death of the outdoors.”‘

If Chouinard gets it, albeit a bit late, isn’t it time for environmentalists on the Colorado Plateau to wake up as well?

THE BEARS EARS DEBATE NOW…

THE ‘OLD WEST’ v THE ‘NEW WEST’ v THE ‘ORIGINAL WEST.’

In the end, the issue of the Bears Ears monument proposal is about much more than just a proclamation by the President, or the designation of specific acreage, or the imposition of new land use regulations, or a list of allowed and banned uses for the 1.9 million proposed national monument acres.

This is about restructuring the social order of the Rural West and it will affect everybody who lives there, for better or worse—Native Americans, Anglos, Hispanics, Asians. Within each of those classifications, one will find extraordinary diversity, which is why the support for the monument varies so dramatically.

I saw an article from the pro-climbing “Access Fund” last week. It said: “We are thrilled to announce that earlier today, the Bears Ears Inter-Tribal Coalition came out in support of climbing in southeastern Utah.” In a letter to the Interior Secretary Sally Jewell, the Inter-Tribal Coalition wrote:

“We believe that the climbers will be committed and effective advocates for good land-use policies and practices in the Bears Ears National Monument. In particular, we believe that climbing should properly be included in the presidential proclamation as a legitimate use of monument lands; climbing has never been mentioned in a proclamation to date but we believe it would be appropriate here.”

Within the Native American community that supports the Bears Ears proposal, it’s clear that many of their views on tourism and the recreation economy are in sync with those of groups like SUWA and the Grand Canyon Trust. The Coalition’s embrace of recreation/tourism dollars deserves some attention.

For example, while the Inter-tribal Coalition may choose to embrace rock climbing, other Native Americans and rock climbers have fought for control of sacred sites across the West, including Devils Tower in Wyoming and Cave Rock in Nevada. Each time, Native Americans, who preferred NO climbing on their iconic sites, were forced to compromise. At Devils Tower, the tribes ultimately and reluctantly agreed to allow climbing for much of the year. Most climbers accepted the ban during June, but others even filed a lawsuit to force total access, all the time.

Josh Ewing is the executive director of the ‘Friends of Cedar Mesa;’ he has been a major supporter of the monument and his organization is partially funded by the Conservation Lands Foundation. The website “Indian Country Today” reported that, he “initially became enamored with the area through his love of rock climbing. He said Bears Ears boasts many climbing areas, but by far the most famous is Indian Creek.’There’s no place on Earth like it, where the cracks are so perfect, and so abundant, and so close to each other,’ he said.”

Other tribal tourism projects have also caused controversy and created serious divisions.

Grand Canyon Skywalk

Environmental groups have subsequently been cautious in their support or opposition. The $30 million “Grand Canyon Skywalk,” constructed on the Hualapai Reservation in 2007 was regarded as a blasphemy by some and praised by others. Traditionalists opposed the tourist attraction, insisting that it was a violation of their heritage, their history and the sacredness of their land. Others saw it as a way to boost the economy by embracing the tourism.

The proposed Grand Canyon Escalade, to be constructed at the Confluence of the Colorado and Little Colorado Rivers continues to generate controversy. The ‘Post-Independent’ reported recently that, “A private development group, Confluence Partners LLC, based in Scottsdale, Arizona, first proposed the plan in 2012, which would occupy 420 acres near the confluence of the Colorado and Little Colorado rivers. The development’s main draw would be the Escalade, a gondola tramway from the canyon rim carrying visitors to a location near the canyon floor”

It would also provide for the future development of hotels, and “a themed cultural and historical, recreation, arts, events, education, dining and shopping experience.” The Escalade would be visible from the eastern edges of Grand Canyon National Park.

Again, the project has caused controversy and debate. The National Park Service, and some environmental groups and Native Americans have adamantly opposed the plan. But according to the Post-Independent, “Navajo supporters of Escalade say the project promises to be of great benefit to the tribe. Many have criticized attempts by non-tribal members to forestall the project. Some have referred to the Hualapai’s Grand Canyon Skywalk, on the south rim of the canyon, as a local success.”

While Bears Ears Monument designation may seem far removed from plexiglass skywalks and gondola escalades, the fact is, an unbridled recreation industry appeals to a broad spectrum of people, who continue to see tourism as the ultimate win-win economy. Many Native Americans have been told that monument designation will help protect their sacred traditions; how many have also been told that it will create a massive recreation economy that traditionally generates low paying jobs, runaway housing prices and dramatically altered living environment? It helps to hear all sides of an issue before anyone can make an informed choice.

Rebecca Benally.

Last summer, San Juan County Commissioner Rebecca Benally expressed an opinion contrary to the more supportive views of the Inter-Tribal Bears Ears Coalition. In her San Juan Record essay, Benally wrote in part, “Trusting the federal government has historically resulted in broken promises for Native Americans.

Benally continued, As a Diné/Navajo woman, a resident of San Juan County and Commissioner, I speak in behalf of my constituents – the Grassroots Utah Navajos…We strongly oppose the Bears Ears National Monument designation in San Juan County on our sacred and spiritual grounds.”

Benally urged caution noting, “Environmental groups trying to sell the idea of a Bears Ears monument purport that the government will agree to allow both a continued access to our sacred lands and management by a Native American Advisory Council….While the lure of a potential job managing the monument may be appealing to some Navajo, empirical evidence would suggest we should not be so quick to believe these promises.”

* * *

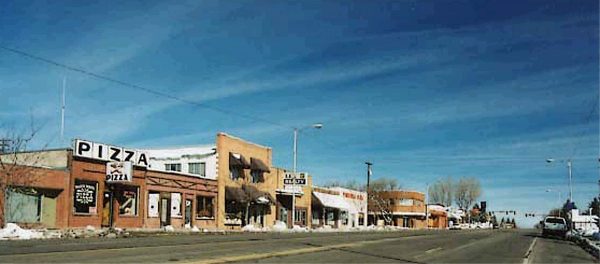

Downtown Monticello, UT.

Proponents of a greatly expanded tourist economy in San Juan County already see it for better or worse, as the ‘Next Moab.’ Both Blanding and Monticello have taken tentative first steps of their own toward that goal. Blanding, a few years ago, even adapted the slogan, “Your Base Camp to Adventure,” on its “Welcome to Blanding” gateway signs.

A couple years ago, the Utah Outdoor Business Network (now euphemistically renamed ‘Public Land Solutions’) addressed the San Juan County Commission to make their case for a dramatically expanded tourist economy.

Ashley Korenblat, the chief spokesperson, made a pitch to those capitalist instincts when she told the commissioners, “…one thing that I want to make clear is that we’re not the conservation community…Our viewpoint, our interest, really derives from recreation and the businesses associated with that right now.

Korenblat explained, “You’ve got to advertise to get people to come and to encourage people to start the businesses…”

The question is, how badly does San Juan County want to be the next Moab? Because when Ashley Korenblat talks about a more vibrant recreation economy, the unspoken goal is to transform rural Utah Mormon communities into something more palatable to the same people who now make Moab their “base camp to adventure.”

In Monticello, the recently completed $13 million Four Corner School “Discovery Center” was promoted as a way to help a floundering economy and add some diversification to the town’s business community. It’s a sentiment and an economic strategy often embraced in small rural western towns with shrinking populations and sliding economies. What most proponents fail to grasp, until it’s too late, is that these kinds of economic infusions rarely help the citizens they are intended for…the ones who already live there.

While the Discovery Center is advertised for its educational aspects, even its supporters expect it to boost the tourist trade there. Just last week, a large sandwich board sign at the Center’s entrance promoted its new “BOULDERING WALL.” Many fail to see the connection between rock wall climbing and educational activities.

For the Discovery Center to become a reality, much of its funding came from the same wealthy benefactors that keep organizations like the Grand Canyon Trust and the Southern Utah Wilderness Alliance flush with cash.

More specifically, it was funded by some of the mega-wealthy who occupy seats on the Conservation Lands Foundation (CLF), the very group funding the Bears Ears initiative. Hansjorg Wyss and Jennifer Speers are both CLF and Grand Canyon Trust board members. Another Discovery Center donor, venture capitalist David Bonderman, is a GCT board member. The Executive Director of CLF, Ed Norton, is employed as a “senior advisor” at TPG Capital, Bonderman’s massive private equity firm.

Many of these donors were motivated to contribute because they thought the Discovery Center was a way of striking a blow against what they deemed to be a very far right, ant-wilderness, even militaristic population in San Juan County. The donor list was not made available to the public until construction on the center was underway.

The list of Four Corners School/Discovery Center recent ‘gear sponsors’ sounded like a roll call of Outdoor Industry Alliance (OIA) members, including: Adventure Medical Kits, All Terrain, Backcountry.com, Black Diamond, Camelbak, Camp Chef, Clif Bar, Columbia, Crazy Creek, Eureka, Falcon Guides, Hi-Tec, Hyalite, Jansport, Kahtoola, Katadyn, Keen, Kelty, Osprey, Patagonia, Petzl, Princeton Tec, Polar Bottle, TEVA and Timberland.

Clearly, the push to make Monticello another ‘New West’ town has been in the works for years. The Bears Ears proposal, whether they’ll admit it or not, must be good news for at least some of those San Juan County citizens who have backed the Discovery Center.

* * *

Some will argue that Moab and Monticello are two very different critters and that to assume the same revolution that hammered Moab will strike San Juan County is a mistake. It is true, Moab has always suffered from a Boomtown mentality, while Monticello has clung, so far, to its insularity.

But recreation supporters insist that high-paying jobs will come from a tourist/recreation-based industry. And to make her case Korenblat points to, “the loads of people leaving Salt Lake City to move to Moab.” But isn’t that the point? Her Grand Plan helps the “loads of people” who live elsewhere, who see an opportunity to cash in on what they perceive to be a depressed economy in San Juan County. And at whose expense? The people who already live there.

Meanwhile, fifty-five miles north, the template for this kind of economy—Moab—suffers from a paucity of affordable housing, low wages, increased traffic to the point of gridlock, and in general, a degraded lifestyle.

But Moabites who like the community’s recent transformation and the proposed monument see it differently. One Moab activist deeply involved in the development of mountain bike trail infrastructure in Grand County and a monument supporter recently posted these comments on facebook:

“Certainly there are many socio -economic problems (in Moab) but many of them are self induced…Startng wages for a line cook in this town is fifteen a hour.. tips are a unrecordable income in Moab, waiters and waitress, guides all make a very good living here, and get to live the lifestyle they chose with big blocks of time off. There is however a part of our population that is unwilling to work at service jobs by there (sic) own choosing. Holding out for those high paying extraction jobs which come and go.”

“Fifteen dollars an hour.” In a tourist town, a line cook might hope to work eight to nine months a year. Even if he/she could keep the job all year they could look forward to an annual income of about $30,000. How does that kind of income mesh in a community where starter homes go for $250,000, where rentals exceed $1200/month (if you can find one), and where the cost of living in general punishes those very same line cooks?

These observations suggest that for ‘Old Moabites’ and by inference, other rural westerners, their inability to find employment is their own fault. They’re saying, in effect: If ranchers and miners and other ‘Old Westerners’ can’t accept jobs as swing shift line cooks, they have no one to blame but themselves.

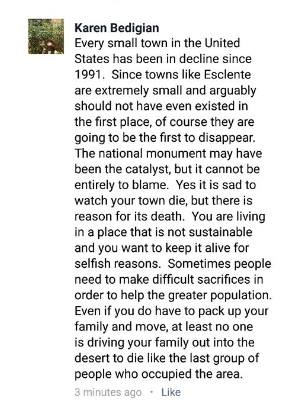

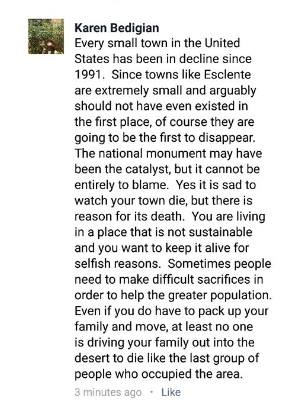

It’s a point of view that is pervasive among urban environmentalists who support the monument. No one expressed it more succinctly than monument proponent Karen Bedigian, who expressed her views on the future of the rural west in this remarkable facebook post:

Every small town in the United States has been in decline since 1991. Since towns like Esclente [sic] are extremely small and arguably should not have even existed in the first place, of course they are going to be the first to disappear. The national monument may have been the catalyst, but it cannot be entirely to blame. Yes it is sad to watch your town die, but there is a reason for its death. You are living in a place that is not sustainable and you want to keep it alive for selfish reasons. Sometimes people need to make difficult sacrifices in order to help the greater population. Even if you do have to pack up your family and move, at least no one is driving your family out into the desert to die like the last group of people who occupied the area.

Every small town in the United States has been in decline since 1991. Since towns like Esclente [sic] are extremely small and arguably should not have even existed in the first place, of course they are going to be the first to disappear. The national monument may have been the catalyst, but it cannot be entirely to blame. Yes it is sad to watch your town die, but there is a reason for its death. You are living in a place that is not sustainable and you want to keep it alive for selfish reasons. Sometimes people need to make difficult sacrifices in order to help the greater population. Even if you do have to pack up your family and move, at least no one is driving your family out into the desert to die like the last group of people who occupied the area.

In other words, it’s time for the rural west to go…In the view of many, it’s simply time for the ‘Old West,’ and even the ‘Original West’ —the Native Americans that came first—in fact, anyone who clings to traditional lifestyles and customs and occupations–to step aside for an amenities/recreation/tourism-driven New West economy. Resistance, they believe, is futile.

SOME PERSONAL THOUGHTS ON THE ‘OUTLIERS’…

This is partly personal. As I noted earlier, the fight over public lands in the West has been ongoing and rancorous for 40 years. I arrived in Moab at the beginning, just as rural Westerners were feeling the effects of the recent changes in the way the federal government managed its public lands. The ‘debate’ since then has grown increasingly ugly, contentious, mean-spirited and divisive. Most of the ‘bad behavior’ reported by the mainstream media is generally attributed to the ‘locals.’ Numerous media reports remind everyone that public lands belong to everyone and claim that “the ‘locals’ just want it all for themselves.” Frequently, they portray rural Westerners as uneducated, militaristic rubes.

But that hasn’t been my experience. What the ‘locals’ would appreciate, I think, is to be treated with some respect. As I noted earlier in this article, the matter of public lands in Utah was decided a century ago. Today’s rural Utahns have tried to work within the framework of those decisions ever since, with varying degrees of success and cooperation.

Whatever your political affiliation or bias, there are the good and bad among us. I know of conscientious ranchers and careless ones. I know responsible tourist guide services and reckless ones. I encounter businesses of all stripes and colors, whose goals are sometimes motivated by honesty and integrity and others by greed.

I know that within the anti-wilderness movement, there’s been a relative handful of protesters whose objections to federal land policies have led to threats of violence and insurrection. And I know their equivalent, on the other side, who have untold amounts of money at their disposal, who wield it broadly to push their own agenda for the administration of public lands.

But please…the vast majority of rural Utahns don’t “want all the land for themselves.” They’d simply like to be recognized as the people who in most respects have been better stewards of the land than many of their critics will admit. Even longtime Utah environmentalists conceded that point, even if they don’t realize it…

* * *

For a very few surviving Utahns, the fight over the proposed monument may have a familiar but ancient ring to it. Eighty years ago, in 1936, rural Utahns learned of a proposal by the Roosevelt administration, and championed by Interior Secretary Harold Ickes, to proclaim a massive 7000 square mile “Escalante National Monument” across much of southern Utah. The locals were stunned.

San Juan County’s Charlie Redd spoke for the grazers who said that if the monument was created, it would mean “financial ruin to a majority of the people in five counties.” He said that the people “who pioneered the roads and schools” in the area “should be given consideration when their basic industry is placed in jeopardy.” Though Charlie made it clear he wasn’t against recreation, he pleaded for “some kind of compromise that wouldn’t completely destroy the livestock industry” in southern Utah.

Brooke Williams

Escalante NM never happened, and SUWA’s Brooke Williams (spouse of SUWA board member Terry Tempest Williams) recently reminded San Juan County residents of that lost bit of history. In 2010, at a presentation in Monticello, Utah, Williams noted that of the original 7000 square mile monument, “political forces shrunk the 1936 proposal down to what eventually became the 500 square mile Canyonlands National Park in 1964.” He added, “Subsequent designation of Capitol Reef National Park, Glen Canyon National Recreation Area and the Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument filled in some gaps in the ‘completion” process.'”

But then Williams made a startling observation. He wrote, “Most stunning is the fact that…most of the public land left out of that original proposal are still natural enough—wild! enough—to warrant permanent wilderness protection.”

Eighty years after the area failed to receive the environmental protections insured by national monument designation, most of the 6500 square miles, in the view of the Southern Utah Wilderness Alliance, remains pristine enough to call wilderness…

I wonder how that happened…

At the end of the day, we have to ask—do the remaining wildlands of southeast Utah deserve protection and care? Absolutely. But will national monument designation provide those protections?

Or will the inevitable marketing and promotion of a new monument in southeast Utah bring untold masses of people to the area? Will it create a completely new list of impacts and damage to the resource and to the communities that are found near it? In a matter of decades, we may find that monument designation has destroyed the very qualities in the Bears Ears area that proponents are trying to protect.

Just like Moab.

JIM STILES is the founding publisher of The Zephyr.

Click Here to Read “THE FUTURE? BEARS EARS NATIONAL ‘MONEY-MINT’ and More Facts & Opinions…by Jim Stiles” From the August/September Zephyr.

Click Here to Read “Some Heretical Thoughts on the Proposed Bears Ears National Monument” by Jim Stiles, From the June/July Zephyr.

Save

Save

Save