Abbey

had a surprise for me when he came over once to see me. With a grin, he handed

me a copy of his new manuscript, The Monkey Wrench Gang. "Here it is, tell me

what you think of it."

Abbey

had a surprise for me when he came over once to see me. With a grin, he handed

me a copy of his new manuscript, The Monkey Wrench Gang. "Here it is, tell me

what you think of it."

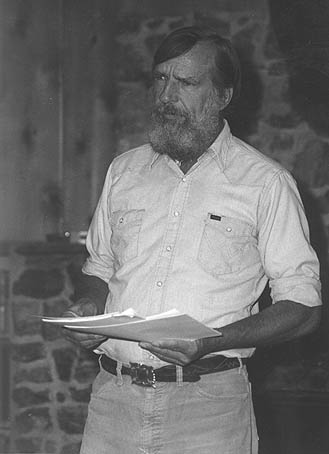

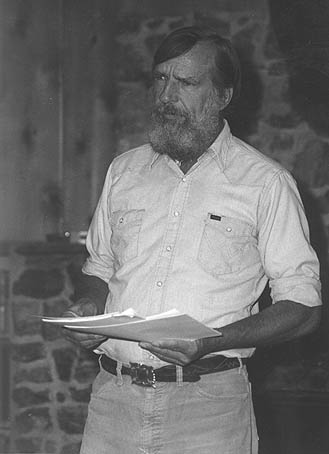

My dear friend Edward Abbey died ten years ago on March 14, 1989. He was only 62 years of age, about three years older than I am. As I approach 70 years, I realize the preciousness of the extra time he was not allowed to enjoy as I have. His death, ten years ago, seemed an unbelievable nightmare to me. It's been an emotional and intellectual struggle without him, and I deeply feel the loss we all have shouldered.

We have risen above that void, as we had too. Rather now, we're aware of the grand legacy he left us. His enlightened wisdom will filter down to benefit all of us in the years ahead. And from it all, he has left us a treasure, a symbol, a working tool...a monkey wrench.

We were destined to meet, Abbey and me. It seems years ago that he arrived for work at Arches. His exalted classic, Desert Solitaire was published in 1968, and I sent him a fan letter soon after. Writing back in appreciation, he noted that we ought to finally meet to tell some lies.

That time came when I pulled into historic Lees Ferry, the famed old crossing of the Colorado River, to start a Grand Canyon river trip. Having backed the truck and trailer to the river, and starting to unload, Peggy, my helper, whispered to me that a ranger was coming down the ramp, probably to check me out. Glancing up, I encountered ranger Ed Abbey for the first time.

He had been expecting me. After the greetings, Abbey pitched in to help us unload the truck and rig the boats. I handed Abbey a beer and we continued working and talking. It was a magnificent evening, and we were the only ones putting on the river.

The job done, the three of us sat on the edge of the raft talking and thinking, eating and drinking until the wee hours of the morning---making creative commentary on how best to eliminate the Glen Canyon dam. We mumbled on and on and I soon realized that this here Abbey was a new breed of ranger.

As Abbey listened (and he was a magnificent listener), I prattled off to him the world's woes. I mentioned our initial futile protest demonstration against the Glen Canyon dam a number of years before. There were only about ten of us then, the Quist brothers and other intrepid souls. We vented our rage, stomped our feet, held up traffic, and passed out leaflets. The Park Service said we had to have a permit to expound on government property, and the Page people stole our signs.

So much for free speech.

Sitting on the boat we spoke of the enormous destruction that had taken place. The thousands of ancient ruins and sites now gone. Gregory Natural Bridge buried. Hundreds of beautiful side canyons flooded, and the severe damage to Rainbow Bridge National Monument. And we stammered on as to the futility of our law suit to protect these national treasures.

"Have another beer, Ed," and we conversed longer. Far into the night. Some one needed to demolish the dam. It had to come down. How was it to come down? Gallant river guides have debated that question for many years on many river banks. Maybe a precision earthquake is the answer, Abbey noted, but that would mean calling on the Creator himself. Great minds have created ingenious means to accomplish the task. Many good ideas, but still the goal hasn't been achieved.

After other rounds of beer, Peggy reminded us we needed some sleep, so we retired for the evening. Abbey to his ranger trailer, and us to our sleeping bags. We made some headway, we thought, toward solving these horrendous problems. Three hours of sleep were all we needed anyway.

At daybreak, Abbey appeared at the river to help us load the gear on the boats. That done, I left for Page in my truck to restock the beer, get more supplies, and pick up my guests. Back at noon, the orientation over, life jackets on, the people loaded, we took off down river. Peggy decided to stay with Abbey for a couple of days (she was to drive my truck to Diamond Creek and then hike down to meet me at Phantom Ranch). Then a couple hours down stream, here comes Abbey in the ranger power-boat to watch me run Badger Creek Rapid. As Abbey pulled along side, he yelled, "Ken, we'll take that god-damned dam down yet!" Seeing us make a successful run and still alive, Ed waved a friendly salute and I waved back.

The trip was successful. All as planned. And Abbey, still at the ferry, pondered new plans.

Things were changing a bit for me. After a pleasant existence in Escalante, a difficult time in Bountiful's suburbia, and finding myself single again, I moved myself and my operations to the quiet town of Green River. Those were choice days in Green River. A kind of hermit existence, between marriages, an interlude. And I enjoyed its liberation. Here were the likes of outfitters Robert, Clair and Richard Quist, ("the Quist boys"), Moki Mac Ellingson, Dave Mackay, Dee Holliday, and all of their boatmen, swampers, and groupies.

Abbey passed through quite often, stopping to visit and enjoy a beer at my makeshift warehouse---a former small garage that now housed my boating equipment, my books, a bunk, a hot plate, and me. It lacked inside water and a toilet. We'd often join the river camaraderie at Ray's Bar and at the Quists' house. Moki Mac dragged his trailer next to my warehouse, and so there was always some grand entertainment.

And it was about this time that Abbey bought some river-side property a few miles upstream from the town. He appeared periodically to kick dust, enjoy his spread, gaze out at the bookcliff scenery, frolic in the river, play poker with his comrades, dream and muse, and lay up details for his stories.

It so happened that near his acreage, additional land on the river was for sale. Known as the Willow Bend Ranch, it contained all of 60 acres. Abbey asked me if I wanted to join him in the purchase. Just the very thought of it, like returning to a life on a farm, was extremely alluring to both of us. After the purchase, I moved out to Willow Bend and set up quarters in a small one-room cabin that stood under lofty cottonwood trees facing the river. A quiet and contented life style, I had no phones and few visitors. Abbey would come around once in a while to check things and help me dig ditches, irrigate the fields, or to fix fence.

We had very few disputes in all of the years in working together. However, one day he appeared with some cotto-salami, a loaf of bread, and some beer intending to fix fence. The farm was in a state of disrepair and there was much to do. The old fence line, much of it, was covered with rabbitbrush. I proceeded to cut and slash the brush out in order to expose the fence line. Abbey stood back staring at me as I continued chopping away. Then he sauntered over, looked down at me. "Why are you chopping out the rabbitbrush," he asked. He always asked lots of questions. I glanced up, and I could see by his manner that he was not at all pleased.

"It's entangled in the wire. It's just a weed. And it's a fire hazard. If a fire started, it would take out the whole fence line," I countered.

Then in a forebearing but instructive manner, he pointed out to me that the rabbitbrush was shelter and a haven for wildlife---rabbits, birds, and such. There were pheasants, magpies, ravens, coyotes, squirrels, occasional bears and other forms of wildlife that surely needed a cover. And not only should we leave a cover for them, he said, we ought to grow additional thickets of brush for their protection.

In the end we got together. Simple reasoning. Rather than whack out all of the brush, we would just cut off the branches that actually interfered with the strands of rusty wire and rotted posts. It took much longer to do it that way, and we endured more scratches over our arms, but I came to understand his views and how much this meant to him and to the wildlife. Quite a teacher he was.

Abbey

had a surprise for me when he came over once to see me. With a grin, he handed

me a copy of his new manuscript, The Monkey Wrench Gang. "Here it is, tell me

what you think of it."

Abbey

had a surprise for me when he came over once to see me. With a grin, he handed

me a copy of his new manuscript, The Monkey Wrench Gang. "Here it is, tell me

what you think of it."

I took the manuscript with me on a trip to the Dolores River. There I spread myself out on the cool sandy beach under the shade of a large cottonwood tree. Reading the whole thing in one day, it was the most riotous and rowdy thing I'd ever read. What a heroic and diabolical story it was. Monkey wrenching! Like the Luddites of old England! Before giving it back to him, I read it again to make damn sure that no disgusting gem of thought was missed. Having blessed it, I returned it to Abbey. He published it in 1975.

The Monkey Wrench Gang was a rousing success. It came at a time the earth was being ravaged and the world was going to hell. Some good folk responded. Dave Foreman, Bart Kohler, Mike Roselle and Howie Wolke and others founded Earth First! Its slogan: "No Compromise in the Defense of Mother Earth." Damn good.

We decided to sell the farm. Life was just too full. We both realized that we "couldn't go back home again." Too much water had flowed under the bridge. He was writing and I was river running, and the property payments seemed formidable. We sold it to Bill and June Adams, old friends of mine, who now have a fine home there. Bill had filmed many canyons while boating in the canyons with me through the years.

I return to Willow Bend from time to time. The memories are delightful still. For Abbey, some of his experiences there are expressed in backdrop and location scenes in The Monkey Wrench Gang.

Time passed with new adventures. Taking a river trip down the Grand Canyon, I had the great fortune to meet Jane, my future wife. A couple of years later we joined our lives and our assets and moved to Moab. This woman was filled with ideas, a woman of action. Searching about, we found that Pack Creek Ranch was for sale. With Jane's youth, energy, perseverance, we were actually able to acquire the property.

Following the purchase, Abbey and his wife, Clarke, then living in the Tucson area, bought some of the land. With their young children, Becky and Ben, they moved to Pack Creek for a while and stayed in the leaky old "Road House." Abbey chose the small log cabin adjoining the house for his writing studio. He moved in a chair, set up a small table, placed his typewriter on it, spread out his papers, and went to work.

Often I'd walk over to the cabin, listen to see if his typewriter was clicking away, and if so, I'd slip away to allow his creative thoughts to flow. At times, he would come out for air, and then we'd chat over the fence line and discuss things of immense importance.

The years passed quickly. We had accomplished much. Though he was only 62 years of age, his health was rapidly deteriorating. But still he continued his work. On a book tour in Salt Lake to autograph his new novel The Fool's Progress, Ed flew to Salt Lake from the Moab airport. I met him at the bookstore where he looked tired and not feeling well. After a night's rest, he appeared a bit better.

On our drive back to Moab, we chatted much of the time, except for the moments he napped. It was good to be with him, we chatted about lots of things. He told me, in some graphic detail, of his next book, Hayduke Lives. We had some hilarious laughs discussing the characters and subjects of the story. He seemed glad to have finished it.

In Moab, I dropped him off at his car, and invited him to stay with us for the night, but he had yet another autograph party to attend to before going back home to Tucson. He really wanted to get home.

After some time had passed I phoned him. Clarke answered and told me that Ed was in the hospital. She'd call me when she knew more about his condition. Abbey had been ill a number of times before, and I knew he'd bounce back. A few days went by without hearing from Clarke, but on March 14, she called. Ed had died. He was to be buried in the desert.

I don't remember what I tried to say---maybe like offering to help or some words of deep sympathy or something like that. But words failed to come. After a goodby, I put down the phone, walked down to the barn and petted and talked to my horses. Then I returned to the office and Jane joined with me.

News of Abbey's death spread rapidly across the nation. The phone rang and Jane answered. A reporter at National Public Radio wanted to interview me. I declined. Just before noon the determined reporter called once again begging for a story. By now I thought I could better handle myself. The public wanted to know more. The reporter asked how I felt about Abbey, and I think I told him of his greatness. And then he asked whether Abbey had ever done some actual monkey wrenching he had written about in his novels. I mumbled something, excused myself, and hung up.

Good friend Terry Tempest Williams was at Pack Creek doing some writing on her pending classic, Refuge, a story about her own feelings and her grief with her mother's cancerous death due to the fallout from atomic bomb testing. We talked of our friend Abbey, and her gentle supportive words greatly helped all of us through this.

We wanted and needed a memorial service of some sort. And Terry was instrumental in bringing a number of Ed's friends, other eminent writers, to Arches National Park. And many others came to express their thoughts in remembrance of their distinguished friend. The service helped ease some of the grief that many of us experienced. Then that night at Pack Creek Ranch, as Ed would have wished, his friends danced, and sang and partied the night away.

Ken Sleight is a regular contributor to The Zephyr.