Brant Calkin is the best damn environmentalist that ever worked on the Colorado Plateau, and he,s done more to protect southern Utah wilderness than anyone alive or dead. He created the strategy for saving the canyon country that's been followed successfully for the past decade, set the tone for the wilderness debate, was mentor to a slew of activists, and built the Southern Utah Wilderness Alliance. And he did it with a quiet humility, integrity, and basic decency towards both his opponents and friends.

SUWA's beginnings:

In 1987, after Brant finished a thousand mile kayak paddle with Susan Tixier down the coast of Baja, he learned from his messages that the Southern Utah Wilderness Alliance needed an executive director. He traveled to Salt Lake City for an interview two days later, and moved to Utah to take the job that week. We should all be grateful.

SUWA wasn't much back then: 1300 members, an unbalanced check book with little in it, and a Rolodex that ignored the alphabet. It did have the tradition of not being intimidated, a remarkable trait given not a single other public lands environmental group has survived in southern Utah either before or since. Hostility did not faze Brant: the Manson family (yes that Manson family) once threatened him over his efforts to save the Redwoods in California. Brant took a fiery and dedicated, but relatively insignificant group and built it into a force that, along with an amazing grass roots network, would stop an anti-wilderness bill supported by a united congressional delegation (a first), change the way the BLM managed public lands, and win important concessions from a reluctant democratic administration.

Brant had a long history of environmental activism before SUWA. It started when Dave Brower came to Sante Fe in the 60's to speak about plans to build dams in the Grand Canyon. As Brant puts it, "I'd never actually been there, but it seemed like a bad idea, and I got into the dam fight." Then Ed Wayburn came to Santa Fe and told about the fight to save redwoods. "I had never seen any, but saving them seemed a good idea, so I got involved in that, too" explains Calkin.

From there it was a seemingly endless series of fights on power plants, predator control, air and water pollution, urban sprawl, mountain lion protection, and wilderness designation.

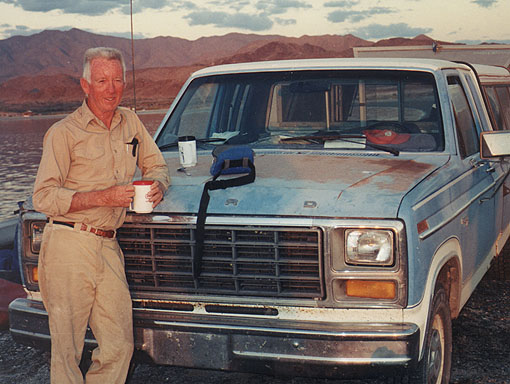

In the early 70's Brant began bombing around the southwest as an organizer for the Sierra Club, sleeping in the back of a Citroen station wagon with an empty pistol holder on the dash as a deterrent. He served as the Sierra Club National President. He turned down a D.C. job with Congressman Bill Richards (who called Brant "a burr headed hippie") because he had more pressing business: roofing his house. He was the Secretary of the New Mexico Department of Natural Resources until he resigned in protest. Somehow he fit in hiking 1800 miles below the rim of the Grand Canyon (he reports Brower was right---it was worth saving). He ran for New Mexico Public Lands Commissioner, and lost, but not without flipping his plane while taxiing down the highway leading into Shiprock New Mexico.

When Brant started with SUWA, the organization was submitting great responses to environmental impact statements, participating in processes, and generally being good. All of this to no effect. SUWA's only victories had come through appeals and lawsuits. So Brant hired SUWA's first in-house lawyer, a legal tradition that continues today (currently, four SUWA staff have law degrees).

Politicians, Bureaucrats and Enviros

As Brant explains, "environmentalists tend to believe in the fairness of governmental process too readily. Nobody likes to go to court, it's expensive, so we tend to just hang on to our high school civics training too long. For a while, at least, SUWA was probably the most litiginous outfit in the country." And Calkin says it worked: "the record on appeals and lawsuits bears out the contention that the BLM was like having Dracula in charge of the blood bank."

Calkin's outspokenness applies to the current administration as well. "And Babbitt [the current Secretary of the Interior] hasn't been much better than the others. For the first two years of this administration, when Congress was of the same party, he fiddled away many opportunities to start some reforms and refused to start others." Brant adds "when Congress changed hands, he had a vertebrectomy. It is never easy to be Secretary of the Interior, and it's even tougher when Congress is in the hands of another party, but Babbitt has been sleepwalking in some kind of Alice in Wonderland setting." As he puts it (if you ever get a chance, buy this teetotaler a cup of coffee and enjoy his analogies), "Babbitt adopted a routine where he drops into a controversy as if by parachute, declares peace, not even victory, and then levitates up, up, and away." He believes "the recently announced re-inventory of Utah BLM wilderness lands was a good thing, but could have come literally years ago and would have strengthened the hands of good people in BLM, citizen groups and others." He remembers that "[former Interior Secretary James] Watt used his office as a bully pulpit and rallied the bad guys and gave them hope. Right now, if Babbitt were to be re-nominated, I don't think environmentalists would even show up for the confirmation."

Brant says of his long career, "I'm constantly reminded that politicians and bureaucrats are transients in these fights. I can't count the number of Secretaries of the Interior, Presidents, BLM directors, county commissioners, US house and senate members, and newspaper reporters that have come and gone since I started working on BLM wilderness. Our side's citizens tend to be enduring and so do the antis. The "friends" we've had in various positions don't stay there as long as staff and dedicated volunteers, and they don't tend to be the advocates we think they should be unless we push them...hard!"

I was fortunate to be that first lawyer Brant hired, and I doubt anyone ever had more fun than working for Brant and Susan Tixier when they were SUWA's Director and Associate Director (although no one actually used titles back then). As Brant puts it, running SUWA was like "managing a volcano."

He approved sending legal pleadings to a snooty law firm on orange colored paper to celebrate Halloween. He constantly invited his staff to attend meetings when others forgot to do so. As a result, SUWA staff were regularly tossed from meetings- Ken Rait practically made a career out it. On Brant's urging I ended up surprising the hell out of then Secretary of the Interior Manual Lujan at the Halls Crossing airport with a hand shake that lasted until we had a chance to discuss some issues (Lujan had been dodging the enviros and tried to escape my grip like a flopping trout while the tv cameras rolled).

Brant established three goals for SUWA. Nationalize the Utah wilderness issue, build the membership of the organization, and defend the land until you pass wilderness bill. It's a strategy that has served Utah wilderness well for over a decade. When things seemed tough, Brant adopted the attitude of "the poor bastards have us surrounded."

THE UTAH MEDIA and WILDERNESS OPPONENTS:

Asked what has changed about Utah since he started this work, Brant offers that the media has not. "Informed reporting is still in the witness protection program" he says. "If the Utah Association of Counties claimed the world was flat, the Utah press would fail to ask for documentation. If someone drops into Escalante to announce he just located the world's largest deposit of tapioca nearby it becomes true and the environmentalists who question such a thing instantly become demons."

Brant adds of some wilderness opponents, "for some people the Pleistocene was just moving too fast.@ Our adversaries may never understand how much they have motivated us. Volunteers who go to considerable trouble and expense to attend a meeting only to be ridiculed by some local politician or rancher usually control their anger at the time, but the drive home can be a time of building a resolve that will live a lifetime. Nothing sustains us so much as the arrogance of our adversaries."

ENVIRONMENTALISTS SHOULD WEAR THE HAIR SHIRT:

Brant offered his staff low pay but lots of autonomy to "do good and fight evil. The benefit of lousy pay is you get to experiment." Calkin offered low wages because no environmentalist should be in it for the money, and "pay doesn't affect the quality of the staff." He offers as rationale both that environmentalists have an obligation to spend their members' money wisely, and that small salaries ensure that only the passionate keep their jobs. He adds that while experience is useful, it doesn't automatically result in better or smarter actions: "smart young people with fresh ideas are just as important as those who have been around the track a couple of times."

Brant never asked his staff do anything he wasn't already doing. For example, he and Susan Tixier earned a total annual salary of $20,000 between the two of them as Director and Associate Director, about a third of what the current SUWA director makes now. Brant never stopped working, whether it was leading the Utah Wilderness Coalition out of shaky consensus efforts, hustling money, or fixing a fleet a beater SUWA cars (he was renown for resurrecting aging office equipment and trucks). And when it seemed everything was done, he'd start cleaning the office.

COMPROMISE:

Sometimes environmentalists confuse passing a wilderness bill with protecting wilderness. As Brant says, "you can pass a bad bill anytime, a good bill takes time." As I interviewed Calkin, Utah environmentalists were struggling to respond to a crappy wilderness compromise brokered by Utah Governor Mike Leavitt and the Bureau of Land Management. The BLM, as would be expected, performed miserably during negotiations and the result was a proposed settlement of one million acres out of the 2.6 million that qualify in Utah's west desert---an offer no environmentalist could seriously consider. Brant says, "Leavitt would like to cut off the interest in the new wilderness that has been inventoried [the recent inventory raised the citizen's wilderness proposal from 5.7 to 9.1 million acres], and one way to do it is pass a bad bill."

Calkin's advice on the matter is "don't give up future options. What it takes is a favorable congressional attitude. We've demonstrated to Utah politicians they can't pass a bad bill, but the time won't be ripe until they are convinced we can pass a good bill, or their replacements are convinced. If it's in my lifetime, fine, if not, fine. Unlike Idaho, where wilderness has been lost to the timber industry, in Utah we've kept the losses to a minimum---we grieve each one, but they are minimal."

"Those of us in the environmental movement don't have the right to be impatient just because we've worked long and hard," Calkin warns.

Brant quickly rejects the notion that wilderness advocates should settle for a bad compromise, and come back for more later. "We passed a Utah Forest Service bill in 1984 and nothing has happened since except too much land has been lost to chainsaws."

WHAT'S NEXT?

After retiring as SUWA's director, Brant took a SUWA slide show on the road to help stop Hansen's anti-wilderness bill, living in his Volkswagen van to save SUWA motel costs (sleeping at the Newark Airport when showing in Manhattan, and on the streets of the most expensive suburb in the US---Shaker Heights outside Cleveland, where the cops ticketed his van while he lounged inside). He then traveled to Arizona to get Ed Abbey's old truck running and brought it back to Utah where it sold for over $26,000 to benefit SUWA.

Brant currently declares himself homeless. "Probably missed by the census," he adds. He's doing "a little stuff" to save sea turtles in Baja, has a few projects in La Paz, dabbles in Utah, and is available for small projects "stirring up hate and evil" where ever he goes. He's learned how to sail just enough to spend winter months in the Sea of Cortez and, judging from reports, make regular stabs at drowning himself. He has voice mail at the SUWA office in SLC, rents a storage unit in New Mexico, parks his sail boat on the Mexico mainland, gets mail from a forwarding service in Nevada and reads email when he crosses back into the states.

I can personally report that he is as good a partner for a back country trip as you'll find, especially if you want to lounge in the shade while he's out in the 100 degree heat amiably fixing busted sea kayaks. He can fix your car, stare down a D.C. thug, traverse a slot canyon or save the wilderness. He's Mr. Goodwrench, Batgirl, Everett Ruess and Ed Abbey packed in one compact frame. After watching him with strays, I also suspect he can converse with animals.

He offers this final advice for those who love wild places: "whether under Carter or Clinton, Reagan or Bush, we only get what we fight for. It is when we are under attack that we should be at our most ambitious and announce our plan for the most imaginative, far sighted, creative, sweeping, exciting public lands policy and reform that any nation ever conceived. Let our adversaries attack that! If there is anything of which I think we are all too often guilty, it is underestimating the desire of the American people to save our lands and wildlife. We should create an agenda that excites the public in a way which blurs state lines and keeps us from being hostage to those politicians who are the "Worst of the West." And the time to do it is now."

God Bless Brant Calkin.

Scott Groene works as the National ORV Campaign Coordinator for Wildlands C.P.R.