“The wilderness once offered men a plausible way of life. Soon there will be no wilderness. Soon there will be no place to go. Then the madness becomes universal… and the universe goes mad.” Edward Abbey, The Monkey Wrench Gang

On October 15, 1956, a blast boomed through the Arizona canyon country and the construction of Glen Canyon Dam began. By the time work was complete a decade later, workers had dumped 9,600,000 tons of concrete into Glen Canyon (enough to erect a four-lane highway from Phoenix to Chicago). The concrete wall climbed 710 feet high and took seventeen years to fill with almost six hundred vertical feet of water. From above, the flooded canyons look like blocked and swollen arteries ready to burst.

Ken Sleight, a now 82-year-old former river-runner and activist, had lost. Even for all his efforts to preserve the river country he called home, the dam and its waters swallowed entire canyon systems in southern Utah and northern Arizona. The resulting reservoir became known as Lake Powell, which Sleight dubbed “Lake Foul.”

Fifty-four years later, while sipping a Polygamy porter on the porch of his house in Pack Creek Ranch, Sleight glares up against the La Sal Mountains and shakes his head. “The government desecrated the very thing they were set up to protect! It was unjust,” he says. Even six decades past his activist heyday, there’s still a glint in Sleight’s eyes. “I did whatever I could to see that this wasn’t done. They destroyed a number of the beautiful canyons. They flooded them over. That was wrong,” he says, chomping thoughtfully on slices of raw onion as if they’re potato chips.

Originally, the federal government made plans to erect a dam in Echo Park, within Dinosaur National Monument, in order to prevent potential flooding, secure water rights, generate hydroelectric power, and to create a water park. The Sierra Club and other environmental groups reacted, and with great success. The government refrained from damming Echo Park, but with the Sierra Club’s consent, they took Glen Canyon instead.

Before the dam scarred Glen Canyon, Sleight guided about fifteen raft trips a year on the Colorado River, and bristled at  the threat of the impending dam. This indignation led him to join what would be his first of many protests: a small affair of protesters without a permit, carting signs and posters. “When do you have to have a permit just to walk around?” Sleight asks, eyes wide. “And we were stopping traffic around the river of course. And the Park Service down there came over and stole all of our signs. Our hokey signs.” He laughs. “We didn’t know how to do things. If that came up today, boy would we know how, yes, we would know how!” Sleight’s arms fly wide like a bird taking flight, his jaw set.

the threat of the impending dam. This indignation led him to join what would be his first of many protests: a small affair of protesters without a permit, carting signs and posters. “When do you have to have a permit just to walk around?” Sleight asks, eyes wide. “And we were stopping traffic around the river of course. And the Park Service down there came over and stole all of our signs. Our hokey signs.” He laughs. “We didn’t know how to do things. If that came up today, boy would we know how, yes, we would know how!” Sleight’s arms fly wide like a bird taking flight, his jaw set.

Before the dam, Glen Canyon was a kind of sanctuary, largely unexplored. The red rock walls rose like pottery around the river that reflects them, that Colorado red, winding in and out of slices of sunshine. And Sleight, no matter how many tours he led as the rock lit up in the descent of the day, had to catch his breath. Now, the Carl B. Hayden Visitor Center offers free tours of the lake and the power plant, but steel rods have replaced deep, boundless canyons. “One of the thrills of river running is the freedom you feel,” Sleight says. “You’re not regimented. The dam took away the thrill.”

Sleight starts talking hard and fast. “Brower came out, published at Sierra Club, saying that Glen Canyon was ‘The place no one knew.’ Shit, I was river running down there. I knew it! Brower compromised. My great, great friend. I love the guy so much. But I knew they were wrong when the Sierra Club did that. I took Brower down the Glen Canyon. We talked about that on the river bank. After it was dammed. Brower apologized like hell. He cried. I saw his emotion a number of times.”

The damming of Glen Canyon Dam has been described by the Glen Canyon Institute as “among the most tragic of environmental losses,” and groups like the Glen Canyon Institute still work for its demolition. (Thirty-one years after the dam’s completion, Senator Barry Goldwater of Arizona, originally in support of the project, expressed deep regret for having voted in its favor.) The Colorado River was originally named the Rio Colorado, or “Red River,” by the Spanish, and its free-flowing silt and sediments used to churn the water into a reddish-brown hue. But after the dam halted the river’s flow, the sediment sank to the reservoir floor and the water turned blue. The sharp drop in temperature and quality rendered the water among the poorest in the nation, according to the Department of the Interior. As a result, three species of fish became extinct, and five more are endangered.

“Too much to fight against. Too much,” Sleight says, sighing. But boy, how he fought. In the days leading up to the damming of the Colorado, Sleight and six other river-running friends formed Friends of Glen Canyon. Sleight also became the first elected chair of the Glen Canyon Group of the Sierra Club’s Utah chapter. In 1999, he won the David R. Brower award for Outstanding Service in the Field of Conservation. And when Lake Powell flooded Rainbow Bridge National Monument, he sued the government for illegally flooding a national park property. Rather than address the issue, the government changed its laws, rendering the flooding legal and Sleight outraged. “I could have done more,” Sleight says. “Hell, I was just a kid running the rivers. I had my feelings, but I didn’t get out on the front lines so much. I was engrossed in my river running. That was my life. And so I kept going.”

Sleight, whose voice crescendos wildly during his passionate retellings of the old days and the old battles, isn’t beaten yet. Case in point: he yet hopes to see the destruction of Glen Canyon Dam, preferably while he’s still alive (he talks about getting on his knees and praying for the dam to crumble, just like Abbey wrote about in The Monkey Wrench Gang). Case in point: Just last week he tore out a real estate sign pressed into the soft soil of Pack Creek’s property, because it violated neighborhood regulations. Case in point: his wife, Jane, detects a snag in his use of the term “right,” and he argues so insistently that she sets down her buffalo burger to amble inside and find a dictionary. (“It’s the only way to solve this,” she says.) All in the name of justice.

Sleight, whose voice crescendos wildly during his passionate retellings of the old days and the old battles, isn’t beaten yet. Case in point: he yet hopes to see the destruction of Glen Canyon Dam, preferably while he’s still alive (he talks about getting on his knees and praying for the dam to crumble, just like Abbey wrote about in The Monkey Wrench Gang). Case in point: Just last week he tore out a real estate sign pressed into the soft soil of Pack Creek’s property, because it violated neighborhood regulations. Case in point: his wife, Jane, detects a snag in his use of the term “right,” and he argues so insistently that she sets down her buffalo burger to amble inside and find a dictionary. (“It’s the only way to solve this,” she says.) All in the name of justice.

Jane returns, takes her seat in a rocking chair and opens the enormous dictionary. “She always does this,” Sleight says, grinning.

“We used to keep the dictionary out, on the kitchen table,” Jane says. “We haven’t needed it in a while.” She reads from the multi-columned “right” definition, tallying the score as she goes. Right: conforming to what is good or proper. Point Jane. Right: in accordance with principle; fair or just. Point Sleight.

Jane gracefully decides that Sleight wins, and he beams, dimples sinking into his weathered cheeks. She walks back into the kitchen to find some dessert, leaving the dictionary on the table, anticipating that we’ll need it again.

Sleight, feeling reinforced in his argument, continues to define justice, or rightness, as he knows it. “It can mean lying down in front of machines, or tearing down signs, or disrupting meetings or whatever. If you feel so deep down that what they’re doing is unjust, sometimes you have a duty to disobey.”

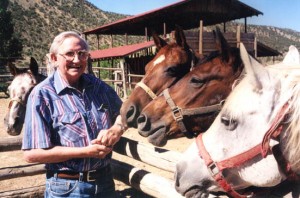

In 1991, armed with only conviction and a horse named Knothead, Sleight fulfilled this duty—he saddled up, rode to Amassa Back Mesa in Moab, and stood down bulldozers before they began to take down several hundred acres of juniper forest. Although the D-9 Caterpillar blades advanced to within inches of his horse, Sleight showed no sign of surrender. And the bulldozers stopped. The publicity generated from Sleight’s audacity precipitated a moratorium on the destruction of the forest.

This “duty to disobey” is likely what earned Sleight his personification in Edward Abbey’s environmentalist touchstone, The Monkey Wrench Gang. Seldom Seen Slim, an ornery Mormon character with features and mannerisms undeniably reminiscent of Sleight, was known for his monkey wrenching of governmental plans. Sleight’s old friend Abbey never formally declared that the character was sketched from Sleight, but to Abbey’s fans and followers, there can be no doubt.

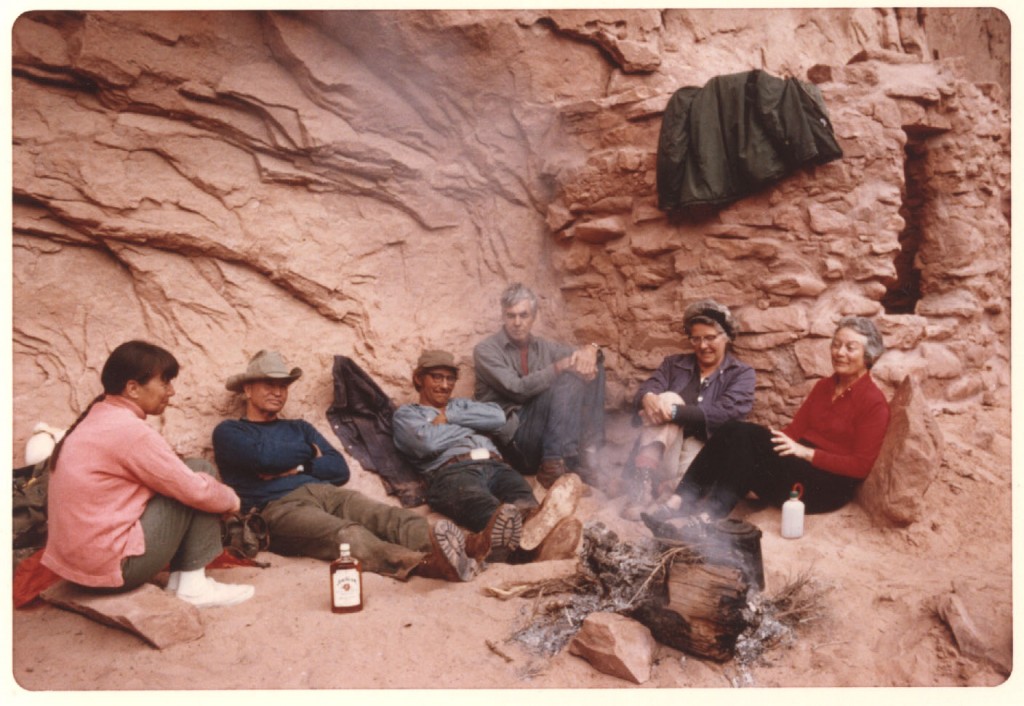

“Yeah, you get an image,” Sleight says, though for many years he would not admit to the similarities. He met Abbey on the banks of the Colorado in 1967, just downriver of the newly constructed dam. Soon they became friends and then neighbors. “Abbey liked people right down to earth. I was so shy and timid all the time. I didn’t socialize too much in the early days except river trips. Still don’t socialize a lot. I’m very at ease to just stay away from people. ”

Jane, who insisted that we sit in the rocking chairs on the porch in order to watch the sky, reappears with bins of sorbet and brownies. “It’s a good one,” Jane notes, nodding toward the swelling sunset that ignites the red dust of Moab. Sleight rates it an 8 on their 1-10 sunset scale. “One night, we had a 12,” Jane says, and her smile mirrors the warmth of the settling air.

Sleight munches on a brownie, eyes locked on the horizon. “Ed and I used to say, let’s go up to the Yukon. Let’s go there. Let’s go there. Where there might be a sense of wilderness. Shit, I don’t need all this, I don’t need a fight. But when I got up there, I said, ‘Boy, this is a good place, there’s wilderness here, and I could enjoy it,’ but there’s always that saying, ‘I want to go home,’ to the red rock. I love the canyons. It was very hard to divorce yourself from something you put your whole life into. And even though they desecrated it, I came back, and fight and fight and fight.”

Sleight has always been willing to fight, but he’s also been willing to change. A self-proclaimed liberal, he cites his days of being a Republican and the gradual shift to the left side before becoming the county Democratic chairman. “When I was at the University of Utah, boy, I was conservative as all hell. I was just like all the other Mormons. I was invited to John Birch meetings. Never did join the son of a…,” Sleight pauses and clears his throat, dimples flashing. “Never did join them, but I went to several of their meetings and read everything. For a while, I was just going right along with it. But I started changing. I’ve grown very liberal. I love that.”

This liberalism, including actually running for county office (and losing) in the San Juan House of Representatives, reinforced Sleight’s feelings of the duty to disobey. He recounts the tale of driving through the Glen Canyon Recreation Area with Abbey, carting a load of beer cans in the back of the truck for recycling. “We got out, and we were so pissed off at everything that was happening… we took those boxes of beer cans and threw them on the road,” Sleight says. “They weren’t supposed to have this dam.” Sleight pauses, and his anger hangs in the air for a moment. “They weren’t supposed to have this goddamn road. They weren’t supposed to have all these things that were so obscene. And it was our way of expressing ourselves. Our own free speech, and so forth. ‘I’m going to shit on your highway.’ That’s what we did.”

Abbey, after all his books and speeches and proclamations in favor of environmentalism, took a hit for rendering the moment into a scene in The Monkey Wrench Gang, in which George Washington Hayduke tosses beers cans out his Jeep’s window . Many previously loyal fans couldn’t see past the littering, which they perceived to be hypocrisy, in either literature or actuality. But Sleight defends his old friend. “You can argue if it’s good or bad, but I think it’s great that he spoke out. In the short term, we can argue that our actions actually hurt the environment. In the long term, maybe it’ll change people’s minds. We need great enlightened minds. We need great people.

“I would do it again. And I would go down, like I’ve done.” But going down has made quite a story. As the light fades on the porch, Sleight details the book he plans to write. “That book thing has been a joke all these years. I’m not going to get it done,” Sleight says with a nod. He’s made several references over the past couple days to the book he will someday publish, and this is the first negative one.

Jane clears her throat and seems defensive, for his stories; for him. “You could,” she offers.

“I would like to,” he says. “It’d be memoirs. I’ll tell everybody what I think. There’ll be some history. There’ll be some philosophy. It will tell all about this area, and people are going to be intrigued. But I get discouraged; I have so much to say. It’d be a book for my kids! All the damn people out there, they won’t read it, but I’d like to see my kids read it. And my friends. If it wasn’t for that, to hell with writing.” Jane nods, satisfied, and carries the melted sorbet back inside, refusing help with dishes.

philosophy. It will tell all about this area, and people are going to be intrigued. But I get discouraged; I have so much to say. It’d be a book for my kids! All the damn people out there, they won’t read it, but I’d like to see my kids read it. And my friends. If it wasn’t for that, to hell with writing.” Jane nods, satisfied, and carries the melted sorbet back inside, refusing help with dishes.

Sleight takes a swig of beer and continues, “But writing, you always hope you take some of your thoughts and give them to other people. My beautiful thoughts, or my asshole thoughts, or whatever it is. I’m always cognizant of the young people. I would like sometime to be able to help convince the young people to do a hell of a lot better job than we did.”

He rearranges the four or five pens he keeps in his breast pocket, wrestling with this idea, as the moon pokes out and deer meander onto the back forty. He nods, steeling his resolve even against its repeated insufficiency and the walls of the dam. “The thing is, it’s a great life if you don’t weaken. Don’t weaken! So whatever I can give I will give. Even if you have to stand up and look like an asshole. It’s great! Everybody ought to go out on the street and look like an asshole once in a while.

“Honest to god,” he says. “It’s quite a feeling.”

To read the PDF version of this article, click here and here.

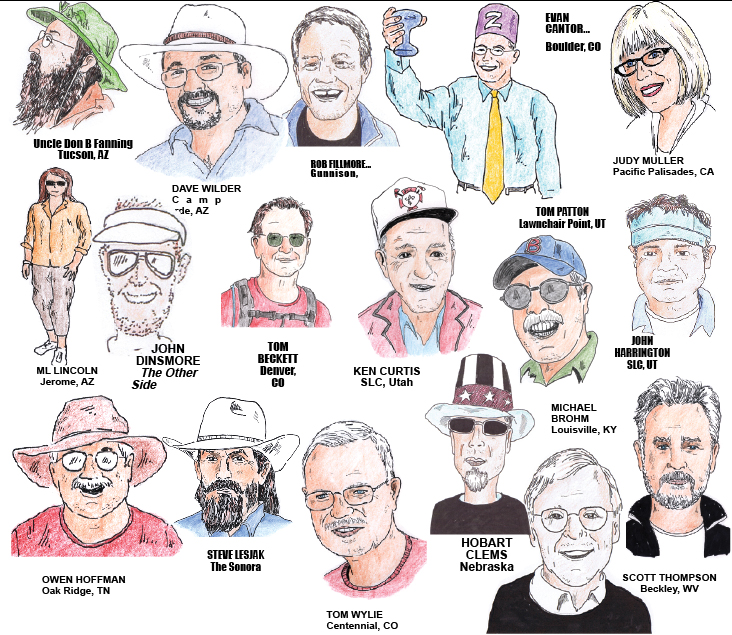

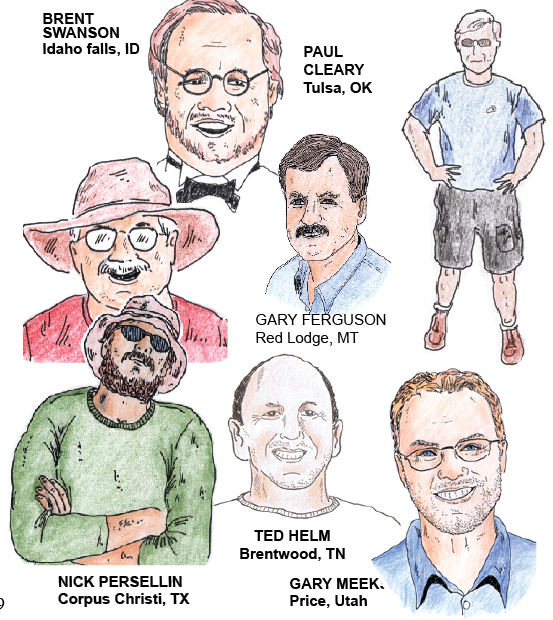

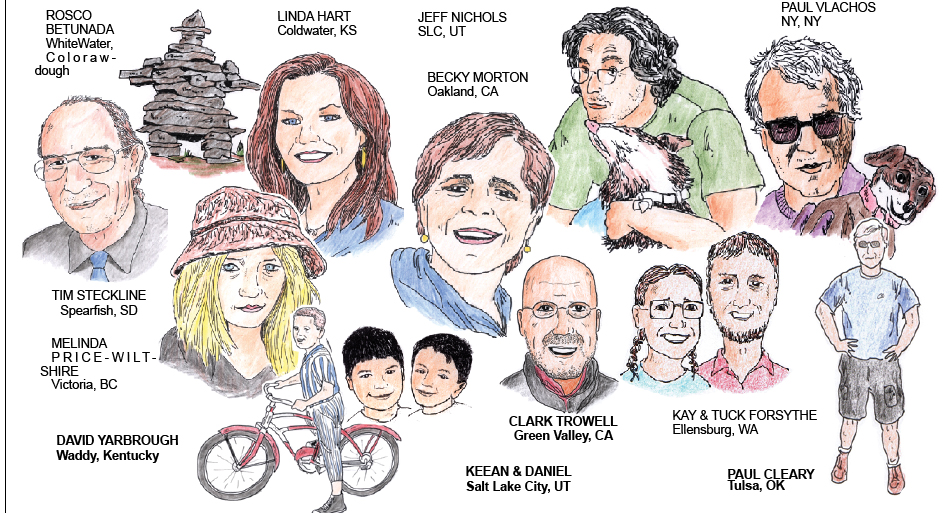

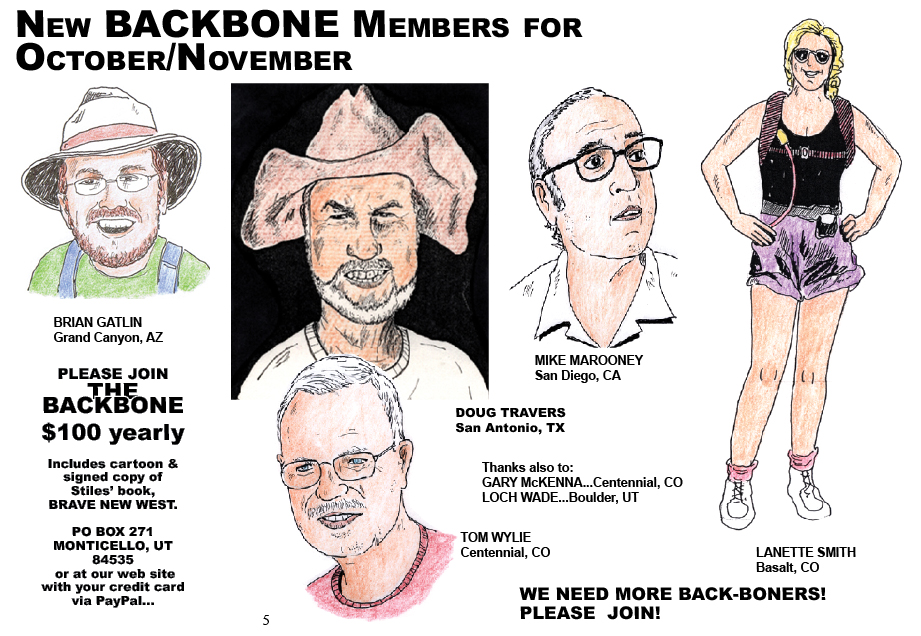

Don’t forget our loyal Backbone members!

pretty cool asshole

it’s too bad it costs so much to stay the night at Pack Creek Ranch… I guess they gotta make the payments, but tourism expenses around Moab have gone right through the roof. Gotta just keep camping. Nice to know that Ken is still fighting the good fight, though.