“After several centuries of experiments and false starts, the foundations of modern Puebloan society emerged from the crucible of post-Chaco chaos: egalitarian, ritually based, anti-hierarchical.” – Archaeologist Stephen Lekson, 2008

It was one of those old motels, shaped like an L, built by the wide open highway in a wisp of a town beneath Colorado’s La Plata Mountains, a little east of Mesa Verde National Park. The small rooms had dark wood paneling, tiny white bathrooms, and opened out onto a tidy, square parking lot. I had come here once before, in March in the early 1980s, winding south from Boulder, Colorado, through snow-suffused mountain passes that I hadn’t had the brains to avoid.

Won over by my nostalgia, or so I like to think, Gail agreed to come with me to this unassuming motel for five days last August. It was the same comely place, but now a double-wide lobby occupied a segment of the parking lot and a stop light suspended by black wires hung over the once open highway.

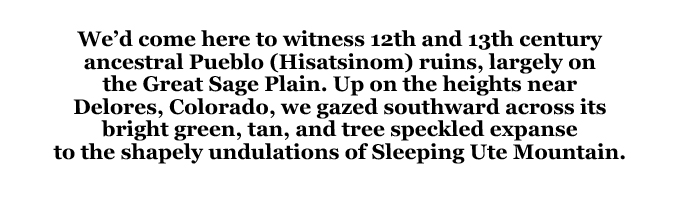

We’d come here to witness 12th and 13th century ancestral Pueblo (Hisatsinom) ruins, largely on the Great Sage Plain. Up on the heights near Delores, Colorado, we gazed southward across its bright green, tan, and tree speckled expanse to the shapely undulations of Sleeping Ute Mountain. The Great Sage Plain expands westward from the corrugated flanks of Mesa Verde. It is a vast, flat space eighty miles long and thirty miles wide, encompassing the town of Cortez, Colorado.

Driving across the Plain, however, it appears as a series of gentle slopes and valleys, scored by narrow canyons. The thin county roads traversing it achieve their directionality through a series of “Ls” along huge tracts of farmland; no need to engineer curving roads out here. This has been farmland for over a thousand years, with the advantage of both winter and summer precipitation. It’s a more elevated expanse than the southern San Juan Basin; therefore more appealing to ancestral Pueblo farmers during their drier decades. The Hisatsinom go way back up here.

The so-called Lowry Pueblo ruins, on the edge of the Canyons of the Ancients National Monument, date back to 1060 CE. They sit on the crest of a low, spreading hilltop, among plentiful sagebrush, rabbit-brush, and Utah Juniper. The site is also stippled with Pinyon pine and dotted with a small, cold-inured species of prickly pear cactus. A stroll out from the ancient walls affords generous views of Sleeping Ute Mountain to the southeast and the Abajo Mountains in Utah.

This 40 room pueblo, together with its impressive Great Kiva, had been an open and accessible place. The people who built and inhabited it must have been prominent, living the good life such as it was; also assuming responsibility for community religious rituals for the diminutive pueblo farmsteads clustered around it.

Walking along the tan and amber colored stone walls of the pueblo complex, I noticed tiny chinking stones mortared between the large ones, and stopped to take a photograph. The previous week I’d seen chinking stones at the Salmon Ruins near Farmington, during the brief New Mexico segment of our trip. Circa 1110 CE the newly constructed Salmon Pueblo had been THE up and coming Chacoan outlier – not for long, but that’s another story.

The chinking stones and several other architectural features mark a connection between Lowry Pueblo and the Chacoan political and economic region headquartered over a hundred miles to the south at Chaco Canyon. This polity had encompassed the San Juan Basin of northwestern New Mexico and southwestern Colorado, reaching as far south as the Red Mesa Valley near Gallup and as far north as Lowry Pueblo. Whether the leaders at Lowry were active participants in the Chaco political hierarchy or loosely affiliated is unclear.

The chinking stones and several other architectural features mark a connection between Lowry Pueblo and the Chacoan political and economic region headquartered over a hundred miles to the south at Chaco Canyon. This polity had encompassed the San Juan Basin of northwestern New Mexico and southwestern Colorado, reaching as far south as the Red Mesa Valley near Gallup and as far north as Lowry Pueblo. Whether the leaders at Lowry were active participants in the Chaco political hierarchy or loosely affiliated is unclear.

Some background on Chaco. In response to tenth century droughts, the elites living in the Great Houses in Chaco Canyon developed “a corn bank,” to borrow a term from archaeologist Stephen Lekson. Surplus corn was stored at outlier Great Houses throughout the Basin, and redistributed to farmers in need during lean years. An intensive ritual system to protect the plenitude of rains grew up at these same locations. At first the ritual and redistribution system seemed to work, but in the long run overpopulation, mono-cropping of corn, and increased farming of marginal land pushed the society beyond a threshold. The Chacoan polity peaked about 1075 CE and then collapsed in the mid-12th century following severe droughts in 1090 and 1130.

A great deal of violence all over followed suit, largely directed against people in smaller farmsteads. To a substantial degree it was perpetuated by other farmers desperate for food and land, but very possibly by the Chaco hierarchy as well, which sought to push the commoners into line. Lekson believes that as the Chaco Canyon religious and political institutions began to crumble the elites moved their capitol north to the impressive Aztec Great Houses along the Animas River, attempting to retain their lordly status over the truncated space of greater Mesa Verde.

Curiously, even though the violence in the San Juan Basin had subsided by the early 1200s, the people in Lowry Pueblo vacated it circa 1225, following 165 years of continuous inhabitation. They migrated south and east; perhaps sensing that a bigger storm was coming.

(Note: as sources, look upon the books of archaeologists Stephen Lekson and David E. Stuart, listed below, and upon the dissertation of archaeologist Scott Ortman, also listed below.)

The motel owners had plunked two black wrought-iron chairs on the four-foot wide concrete walkway outside each room, under the shade of the overhanging roof. In the late afternoons, after a day of tromping around Pueblo ruins, Gail and I would settle into ours, reading paperback books. Me, I’d pop open a can of Diet Sprite and prop my feet up on the warm hood of our rental car.

Gail worked her way through a novel, The Help, which she’d picked up in the Albuquerque airport. I was sinking into Stephen Lekson’s opus, A History of the Ancient Southwest, which I’d spotted in the Visitor’s Center at Salmon Ruins. It has 250 pages of text, plus another hundred of footnotes, the latter in 8 point font (where he put the punch lines), and it weighs over two pounds. In this book Lekson tells you three things: what archaeology shows us about what actually happened in the Southwest, what the orthodox archaeological opinions have been about what happened in the Southwest, and what the orthodox archaeological bullshit has been about what happened in the Southwest. He has the qualities I most admire in a writer: candor, an unfailing nose for absurdity, and an utter lack of professional timidity, bordering on recklessness. Otherwise described as a sense of humor.

Several times we chatted with our neighbors, a fiftyish couple with Virginia plates, as they came in and out. They were visiting their adult daughter in town. As it turned out, the wife was also reading The Help. A terrific book, she and Gail agreed.

***

On a warm blue afternoon, in another area of Canyons of the Ancients National Monument, Gail and I trudged down a narrow trail through a forest of Pinyon pine punctuated by yucca, until we encountered a low pile of tan and blackened rubble beneath barren tree limbs. This was the edge of Sand Canyon Pueblo, which unlike Lowry has not been excavated for scrutiny by the public. I thought that maybe this was a remnant of the outer wall, the one I’d seen in an artist’s reconstruction of the pueblo and later read about: the “one-story perimeter wall that must have made for an impressive sight, daunting to any invaders. But the wall did not hold.” (See writer Craig Childs, House of Rain, 2006, p. 157.)

Sand Canyon Pueblo was huge, with 420 rooms, 90 kivas, and 14 towers, carefully planned and rapidly built in the  1240s or 1250s. It was destroyed in a massacre about 1280. Childs says, “Excavators at Sand Canyon found a bedlam of human bones. The corpses had not been formally buried but instead were left scattered about in the pattern of a slaughter. Death had come quickly to these people, terror reigning down on them…People had been taken down in hand-to-hand combat; these had not been quiet deaths.” (pp. 157-158.)

1240s or 1250s. It was destroyed in a massacre about 1280. Childs says, “Excavators at Sand Canyon found a bedlam of human bones. The corpses had not been formally buried but instead were left scattered about in the pattern of a slaughter. Death had come quickly to these people, terror reigning down on them…People had been taken down in hand-to-hand combat; these had not been quiet deaths.” (pp. 157-158.)

Archaeologist Scott Ortman elucidates: “…violence [in greater Mesa Verde] appears to have involved entire villages, as exemplified by the evidence of massacres at Castle Rock and Sand Canyon pueblos…Violence during the final decades of pueblo occupation, then, appears to have involved inter-village warfare and factional conflict…social conflict was endemic, and…most of the population was concerned for their safety…There is also no clear evidence to suggest that the aggressors were anyone other than Pueblo people…the conflict may well have been internecine in nature.”

I worked my way along the rubble, the successive heaps of bright tan stones, toward the head of the canyon. When I got close I turned and gazed down the slender canyon, my view framed by green boughs and twisted limbs of juniper. The canyon walls, coated with Pinyon pine and juniper, juked out to the right, then back sharply to the left. Within the narrow “V” of the canyon walls there was a pale, creamy blue mountain range, somewhere out in Utah.

The Hisatsinom who selected this site did so with great care, seeking a place where their beloved people could live amid beauty, hoping they would also feel protected and safe.

But alas.

The loveliness of this canyon is haunted by sorrow. The terror and anguish of the innocently slaughtered seems to hang in the air. Maybe it was just my own emotional state when I was present there, but I swear I could feel their anguished energy suspended all around me. I’ll bet many others who have come here have felt it, too.

***

Late in the week we saw one of the motel’s owners, call her Shirley, walking across the parking lot toward us as we stood by our door. She looked to be in her mid-forties, busy with the unceasing stream of tasks and conundrums involved operating a motel. Yes, we told her, we were happy with our stay and yes, we’d gladly recommend the motel to others on a travel website.

We stood at the edge of the parking lot, chatting. She was trying to get her adult daughter to help her run the place several days a week instead of now and then. Gail and I nodded, wishing her the best of luck with that. Shirley was one of those alert, kind, stressed-out, good-hearted small town business people you so often find.

She and her husband and children had moved here fifteen years ago. When we asked what had brought them here she glanced skyward, her face softening as she talked about riding horses out on the long trails.

***

Gail drove first on our way back to the Albuquerque airport, across the plateau south of Durango, Colorado, on U.S. 550. It’s the sparse, spread-out country before you descend into Aztec, New Mexico. A good place for me to ponder on what we’d seen.

The Pueblo Indians insist that their ancestors did not “abandon” Mesa Verde and the Great Sage Plain. For them these ancient villages remain ancestral lands. It’s important to respect that, but it’s nevertheless fact that the Hisatsinom did physically walk out of the entire territory en masse. On this point Lekson leaves no doubt: “When the last villagers left the Mesa Verde area, sometime after 1280, the homelands were truly empty. If anyone stayed behind, we can’t see them archaeologically. The totality and finality of the evacuations suggest to me political rather than environmental processes. Complete depopulation is unusual in history…The disaster that ended Chaco and Aztec was at least in part, and I think largely, man-made: failure of the political system.”

Why political failure in particular? Because the mega drought of 1275-1300 wasn’t awful enough on its own to have driven everyone out. Lekson says, “But here’s the kicker: our most advanced environmental modeling…shows us that they didn’t all have to leave. Even the worst periods of the Great Drought could have supported substantial numbers of people…”

This remarkable phenomenon, a true exodus, dovetails with a persuasive argument by Scott Ortman in his 2010 dissertation that many of the people comprising the Tewa Pueblos along the Rio Grande River in northern New Mexico are descended from ancestral Puebloans who migrated there from greater Mesa Verde.

I suspect that in walking away from their homeland – voting with their feet, to borrow another of Lekson’s expressions – many had reached two conclusions about their society based on the series of disastrous experiences: that those who seek power are the least fit to exercise it and that factional conflict, once it crosses a certain threshold, is incendiary to all. I also suspect they were thinking about how to utilize the intricate religious rituals and other cultural tools they knew, traditions that had once bolstered the elites of Chaco Canyon, to suppress power-seeking and promote egalitarianism. In other words, to turn their culture upside down.

Which they accomplished. Impressively.

I believe we can learn from the Hisatsinom and today’s Pueblo Indian cultures, assuming we have have the humility to accept that in certain crucial respects they have been innovative and successful whereas the mainstream American culture remains mired in an outdated, self-destructive paradigm.

Note – Hisatsinom is the Hopi word for the ancestral Pueblo Indians, which I have chosen instead of Anasazi. The latter is a Navajo-derived archaeological term not favored by Pueblo Indians of today.

(Sources: see Stephen H. Lekson, A History of the Ancient Southwest, 2008, pp. 125-131, 139, 153-156, 158-166, 182-189, 194-200, 225-251, including footnotes; Scott G. Ortman, Genes, Language and Culture in Tewa Ethnogenesis, A.D. 1150-1400, Dissertation at Arizona State University, May, 2010, pp. 168, 183, 479-489, 614-624; David E. Stuart, Pueblo Peoples on the Pajarito Plateau, 2010, pp. 58-75, 120-121.)

Scott Thompson is a regular contributor to the Zephyr. He lives in West Virginia.

To read the PDF version of this article, click here and here.

Don’t forget the Zephyr Ads! All links are hot!

Interesting article. I just finished reading “Anasazi America,” another book by David E Stuart, a pretty good book about this very issue, the origins and buildup of Chacoan society, drought, and finally the “voting with their feet.” The author also makes comparisons to contemporary America which I found informative. Might want to check it out.

how could you know