You’re damn right there’s an immigration problem in Arizona: far too many white people have been emigrating there.

If you doubt that, here are the numbers: while the Hispanic population in Arizona increased by 856,000 between 1980 and 2006, the white population escalated by 1.2 million. (Population

Brief for the State of Arizona, Western Rural Development Center 2008, p.2).

Yet we don’t hear about Latinos in Arizona strutting around in the dry heat, demanding that the white folks move back where they came from.

Why is that?

I think the reason is good ole white entitlement; an attitude that has complicated if not contaminated the touchy subject of overpopulation. I know more about white entitlement

than I care to, having grown up in the small town South before the civil rights movement took hold. The year I spent in Mississippi in 1962 is burned into my mind like they did it with a branding iron. And even though the right wing is (officially) no longer racist, sometimes I hear the same tone of self-satisfied superiority and indignant outrage in the voices of those who fairly spit out the words “illegal immigrants.”

Within these words lies the assumption that we Americans have some righteous claim to the lands comprising Arizona and the Southwest, when the facts plainly show that’s bullshit. That

attitude does remind me of the white people in Mississippi in 1962, who thought they were entitled to the de facto slave labor of the African Americans living there.

The only, repeat only, reason all that land is within the territorial United States is because we stole it at gunpoint from Mexico. Which in turn took it from Spain, which stole it from Native Americans, some of whom stole it from other Native Americans.

It’s quite a daisy chain.

A brief recounting of how America came to possess the Southwest is instructive. In 1846 President James K. Polk concocted an excuse for invading Mexico in order to grab as much

of their land as he could get his hands on. Some members of Congress did have the integrity to question the necessity for war, among them a young, gangling Abraham Lincoln.

But as is true with power-hungry people, Polk would not be stopped. The crushing blow to Mexico was delivered by General Winfield Scott, who in 1847 invaded the port city of Veracruz

and marched toward Mexico City, which he took after six months of brutal fighting. Scott himself admitted that his soldiers had “committed atrocities to make Heaven weep and every American of Christian morals blush for his country.” Translation: they slaughtered civilians.

In the end, the United States paid Mexico $27 million for all that land; a farcical sum in order to whitewash its dishonorable aims.

The great Henry David Thoreau spent a night in jail to protest the taxes to support this war, and then went to his cabin to pen his classic essay, “Civil Disobedience,” which championed an individual’s right to oppose an immoral government. Gandhi himself was later inspired by this essay. (See the textbook Out of Many: A History of the American People, by Faragher et al, 2005, pp. 416-419).

In short: we Americans are in no position to wax indignant about “illegal immigrants” from Mexico entering the Southwest, given that we stole that land from them in the first place.

For the irony-challenged reader: I am NOT talking about giving the land back to Mexico. This is about attitude.

The reason I have written first about racial or ethnic entitlement, whoever may perpetuate it, is that it is the one attitude that will make resolving this great problem of overpopulation impossible. If people fear that the call to reduce our numbers is merely a ruse to weaken them in the face of an enemy, their willingness to cooperate will disintegrate.

Unfortunately, Latinos have grounds to fear just such an attitude. Consider, for example, the notorious Arizona statute known as Senate Bill 1070, just upheld in large part by the U.S. Supreme Court. This law targets Latinos who are American citizens for de facto racial profiling in order to locate “illegal immigrants.”

But not all entitlement is about racial, ethnic, or cultural prejudice. When it comes to overpopulation, there are diverse layers of entitlement spread out among different groups.

Challenging them all is what makes me want to drink twelve Budweisers at the end of the day (and I gave all that up a long time ago).

I would like to explain what’s driving me to get into the turd-laden issue of overpopulation. It’s this: in the late 1960s I fell in love with Arizona. The way it was before its developers, business tycoons, and state leaders systematically destroyed it with their culturally sanctioned avarice. It was as though they had tied a Javelina to a stake and scourged it with tendrils of hairline glass, all the while thinking, hey, this is what good people do.

You don’t forget witnessing something like that. Edward Abbey had a similar experience. In 1959 he rafted through Glen Canyon on “the golden, flowing Colorado River,” to use his words. Later he worked there as a seasonal park ranger.

Ed knew the river and the canyon before Glen Canyon Dam stopped it up like a vast, stinking toilet. He said, “The difference between the present reservoir, with its silent sterile shores and debris-choked side canyons, and the original Glen Canyon, is the difference between death and life. Glen Canyon was alive. Lake Powell is a graveyard.” (The Damnation of a Canyon, pp.1,3).

Ed loved Glen Canyon the way it was. In the late 1960s Arizona was a shifting, turning mosaic of

brilliant colors; everywhere there were crystalline expanses of space and light; the outline of a mountain peak 80 miles away was as clear and sharp as the verdant trunk of a paloverde that you touched with your fingers.

Arizona was: the pervasive beige of the sun-blasted Sonoran Desert outside Tucson, studded with enormous green stalks of Saguaro cacti; the red and gold evening light atop etched black horizons; the state roads heading north, twisting into sharp green blankets of juniper and pinyon pine and red striped sandstone; the rough black lava rocks and the sweet smooth lava cone near Flagstaff, adorned with spare, regal stands of Ponderosa Pine; the burnt-brown edge of the Mojave Desert, stippled with rough-barked Joshua trees, their limbs curving into clusters of spines.

My microbiologist mother first drove me from Tucson to the Navajo Reservation when I was 18. I had no language of description for the Navajo world; I just I called it “the place with no telephone poles.” It took me a long time to find the words for what I discovered there: that once beyond the telephone wires I was in a sacred land, and that these people knew something about the power of the landscape that my own culture had lost. In 1971 my mother died of heart failure in Holbrook, Arizona, while driving to the sacred land.

Now here’s what tripling the population of Arizona in less than a generation did.

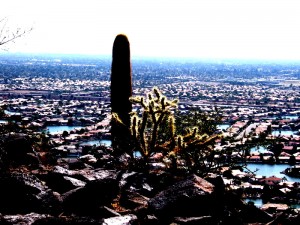

In the summer of 2005, as Gail and I flew into Sky Harbor Airport in Phoenix, we glided over forty contiguous miles of  tract houses; the many thousands of tiny yards and blue dotted swimming pools were packed against each other like cells in a massive tumor. We sped north on the interstate in our economy rental car, but even sixty miles beyond the metropolitan melanoma of Phoenix, scattered human structural litter occluded the adamantine splendor of the land.

tract houses; the many thousands of tiny yards and blue dotted swimming pools were packed against each other like cells in a massive tumor. We sped north on the interstate in our economy rental car, but even sixty miles beyond the metropolitan melanoma of Phoenix, scattered human structural litter occluded the adamantine splendor of the land.

On it went like this. North of Prescott a shapeless growth of bright green golf courses and oversized luxury homes had metastasized far beyond the once compact, historical shape of the town. It went on for miles. The primordial majesty of the Arizona landscape did not open up until we neared the Hualapai Reservation in the far northwestern corner of the state. A territory for refugees, it now seems. For people like me.

In Arizona, you ought to be able to go outside any city or town, look out over the crystalline vastness of the land,and feel something dazzling inside. I call this the enchantment of the land. That’s what’s been destroyed in Arizona. Now you can only find it in special spots: in the national monuments, wilderness areas, Indian reservations, and remote corners of the state.

The enchantment of the land is not some trifling pleasure. It is the fundamental signal the landscape has always given our species that the relevant ecosystem is in adequate health. It is

infinitely more significant, more real, than the Gross Domestic Product or growth in consumer spending or construction starts or even the unemployment rate. Its absence in the landscape is a

blunt warning, like a mass in our lungs on a CT scan.

But our culture, through its self-perpetuating frenetic activity, much of which is crazily entertaining, has long tuned out this signal (witness the Dust Bowl of the 1930s).

The destruction of the enchantment of the land in Arizona was specifically caused by massive overpopulation, overconsumption, and overdevelopment.

For me it’s clear: no human being, whether White, Latino, African-American, Asian-American, Native American, Australian, African, Middle Eastern, European, Asian, or whatever, has

a right to overpopulate any ecosystem, be it in Arizona or anywhere else. The main point is not whether people cross a border or a state line, but whether the carrying capacity of the ecosystem for humans is being exceeded. If so, the population there needs to be gradually lowered by reducing birth rates, emigration from other states, and immigration from other countries, until our numbers are within the ecosystem’s carrying capacity. Probably over several generations.

Which is a politically incorrect position to take.

That’s because a series of perceived human entitlements have grown up over time that are in conflict with the health and well being of our ecosystems. That’s why it’s politically incorrect to broach the subject.

Let’s look at some of these entitlements. But first, I ask you to bear in mind that that a trend that

characterizes a group – think of a bell curve – will often not apply to many of that group’s members. Epistemologically challenged readers may find that fact a bitch to deal with.

The basis for liberal entitlement is a compassionate, but ideologically utopian worldview, often rigidly held, which aims to protect people perceived as oppressed or otherwise vulnerable. I think that as a group, liberals have been avoiding serious public dialogue about overpopulation because they are afraid that efforts to reduce it will be used as an excuse for persecuting vulnerable groups. That’s an understandable fear, but silence isn’t a rational strategy for them in the long run.

By silencing each other and most of the rest of us, liberals may well be endangering the lives and well being of the very people their ideological commitments have sworn them to protect. Liberals may have another problem with addressing overpopulation. For decades the foundation of their politics has been wealth redistribution based on continuing economic growth: they claim that everyone should get at least a narrow slice of the pie. Certainly including themselves. Radically reducing our numbers, however, will bring an end to cornucopia economic expansion. It will mean a satisfying but far less materialistic way of life; something many liberals may not be prepared for.

Right-wing business entitlement is barefaced; right-wingers see themselves as the realists, after all. In order to maximize business profits, and therefore growth, and therefore spiraling profits, they need hordes of frightened, desperate, and therefore compliant laborers to hire and underpay. Cheap labor is to soaring profits as warm ocean water is to growing hurricanes. Reducing the human population will make inexpensive workers more difficult to find, therefore making wages climb, therefore reducing profits, therefore dampening business growth.

And it will reduce consumption, exacerbating the downward cycle. Our metaphorical hurricane will transmogrify into an unremarkable series of thunderstorms, perhaps with interesting displays of lightning.

I enjoy a good thunderstorm.

Right-wingers revere individual property rights. I cannot imagine them putting the health of an ecosystem first if that will limit the profits they can derive from their investments in private property, or will reduce the market value of that property. They will see changes of this nature as de facto Marxism, decrying climate scientists as henchmen in a sinister plot against free enterprise (but of course they’d never hack into scientists’ e-mails in order to conjure “evidence” for such an imagined conspiracy).

Right-wingers revere individual property rights. I cannot imagine them putting the health of an ecosystem first if that will limit the profits they can derive from their investments in private property, or will reduce the market value of that property. They will see changes of this nature as de facto Marxism, decrying climate scientists as henchmen in a sinister plot against free enterprise (but of course they’d never hack into scientists’ e-mails in order to conjure “evidence” for such an imagined conspiracy).

Yet another entitlement is pronatalism, the perceived right to have children up to one’s biological capacity. This has been the predominant tradition since the end of humanity’s hunter-gatherer days.

Pronatalism is backed by big time Western religion.

Consider, for example, the Old Testament’s “Be fruitful and multiply; fill the earth and subdue it…” (Genesis 1:28). In general, Judeo-Christian religious authorities have felt entitled to perpetuate the credibility of their traditional teachings and scriptures, despite Sinai-sized evidence that their pronatalist stances are a disaster for living systems (the Catholic teaching against birth control deserves its own Flat-Earth award, with a free coupon for all the credible books on climate science and climate change biology Pope Benedict and the College of Cardinals are willing to read).

Given that mainstream religions do have a lot of good teachings, why can’t they figure out that to “fill the earth”with homo sapiens means up to, but not exceeding, each ecosystem’s carrying capacity? That they refuse to figure this out in the face of escalating danger to us all is religious

entitlement.

Nevertheless, there is a helpful trend. It’s become clear that as more women are educated and given opportunities outside the home, as well as access to birth control, birth rates predictably drop; at least they have thus far. If humanity does somehow avoid a series of population-related catastrophes, women and the women’s movement will deserve the credit.

The danger, as ever, is complacency. It’s easy to forget that even with lower fertility rates the world population will continue to grow at an alarming rate, simply because there are more people around to reproduce. And that the climate is now unstable for the first time since the beginning of the Holocene 11,000 years ago, and that it will steadily grow more unstable for centuries to come, imperiling fresh water supplies, agricultural production, and of course the ecosystems that

vitally sustain us.

Centuries from now, as teams of archeologists turn their trowels through the debris of our ex-civilization, I wonder if they’ll conclude that we trivialized the most important signal of approaching disaster: the loss of enchantment of the land. Perhaps after a scorching day sifting through the ruins, one of them will lean back and say to her team mates, “You know, it’s like a critical mass of Arizonans way back then, certainly the most influential ones, were walking around with their eyes shut. They literally didn’t see what was happening to the landscape.”

The crew will nod and smile sadly.

Over the years Gail and I have visited the following Indian reservations: Mescalero Apache, Wind River Shoshone, Arapaho, Flathead, Blackfeet, Taos Pueblo, San Ildefonso Pueblo, Navajo, Hopi, Hualapai, Havasupai, Yavapai, Acoma, and Zuni. On every one of these reservations, wherever the tribe has retained enough land and political power, it has carefully preserved the enchantment of the land. While the tribes may explain this differently according to their own paradigms, that’s what they’ve been doing.

My opinion? A critical mass of Native Americans are walking around with their eyes open.

To read the PDF version of this article, click here and here.

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!

But, but, but!… If GDP stops growing how will know if the Great Depression is over?!? How will we measure happiness happiness?!?

At first we won’t, because we’ll be too confused to see what’s different.

Thanks for your comment.