PETE PARRY

Pete quietly took on the D.O.E and the planned Canyonlands Nuclear Repository…

AND WON.

When I was in my early 20s, the National Park Service hired me as a seasonal ranger at Arches National Park. I had virtually no qualifications for the job, other than an unbridled enthusiasm for the canyon country and a self-righteous desire, inflamed by my third reading, cover-to-cover, of Ed Abbey’s “The Monkey Wrench Gang,” to be the Protector and Guardian of my beloved red rocks.

I started my tour of duty at the Devils Garden campground and lived in a small rat-infested trailer that many tourists mistook for Abbey’s; I once hung a sign that read, “This is NOT Edward Abbey’s Trailer,” but the gesture was futile. Tourists continued to knock on my door.

I managed to stay out of trouble for about six weeks. Then one day I got riled about an article that appeared in the local weekly, The Moab Times-Independent, and immediately put pen-to-paper with a caustic reply. I can’t recall the specifics but the issue of development and paving roads probably played a role in my passion. My fiery letter to the editor was so annoying that the editor and publisher, and to many the moral compass of Moab, Sam Taylor, devoted his entire editorial that week to respond. Sam whacked me about the ears for the better part of 500 words. He often referred to me as “this young ranger” who had only been living in Moab and Southeast Utah for the better part of four months, who was now taking time out from his busy schedule as a left-wing, bearded, hippie ranger to tell all the good residents of Grand County how to live their lives.

It was the first time I had ever been forced to consider my own mortality. I was sure someone would shoot me.

The day after the T-I hit the newsstands I wandered into the visitor center and could not help notice that most of my co-workers were avoiding eye contact. Not a good sign. Finally, the park’s unit manager, Larry Reed, spotted me and called me into his office. He had a copy of the paper rolled up in his hand.

“You sort of went overboard don’t you think?” he asked. I didn’t know what to say and before anything came to mind, Larry shook his head and said, “Pete wants to see you.”

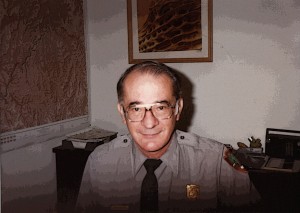

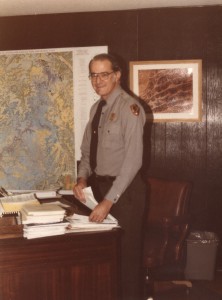

“Pete?” I gulped. “Pete Parry?” I sank into a chair. Pete Parry was the group superintendent of Canyonlands National Park, Arches National Park and Natural Bridges National Monument. He had come to canyon country only a year earlier and so far, nobody really knew what to make of him. Pete was quiet, even taciturn, maybe a bit remote…very different from the first Canyonlands super, Bates Wilson, who had only retired a couple years earlier. Where Bates was gregarious and social, Parry tended to be the master of understatement, and from my lowly perspective, a man who most likely didn’t care for skinny rangers with big mouths. I expected the worst.

I was escorted into his office where I found Pete behind his desk, reading or re-reading my letter. He motioned me to sit down, studied my rant a bit longer and finally laid the newspaper aside. I looked hard for a hint of his mood but the man was inscrutable. He gave me that even gaze…

“Your letter to Sam is getting a lot of attention this week,” he said. “Today, I went to the Chamber of Commerce luncheon, out at the Sundowner, and they even read your letter there. How can I put this…your letter was not well-received by the Moab business community. I think there might be one or two of them that would like to hang you..at least by your thumbs.”

All I could do was grimace. At 22, I thought I might even start to cry and Pete sensed I was losing it. Pete measured me slowly. Had I suffered enough? Pete decided that I had. “Well,” he said chuckling, “First of all we’re not going to fire you. These kinds of things do make my job harder, but I’m not ever going to censor any of you when it comes to expressing an opinion.”

I breathed a sigh of relief.

“But I am going to give you some advice,” he added. Pete leaned back in his chair. “I’ve been known to write a letter like this myself from time to time. Sometimes I know it’s worth the effort and sometimes I know I’m just blowing off steam. So here’s what I do—I write that letter, get it all off my chest. And then I take the letter and put it in a drawer for 24 hours. If, a day later, I still want to mail it, I do. But it helps to give yourself a day to think things over, to let the cooler side of your own brain have a chance.”

It was advice I’d remember and appreciate, if not always apply, for the next 30 years. And it was the first of many conversations I’d have with my fearless leader and the man I’ve been able to call my friend for the past 35 years. One afternoon last month, Pete and I got together to talk about his time at Canyonlands. Few realize how dramatically his leadership altered the future of the canyon country. Some, even today, still bitterly disagree with the direction Pete took the park. But for most of us, Pete was a visionary.

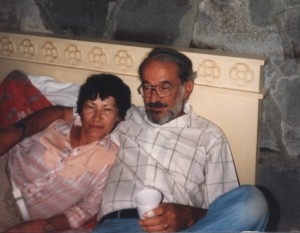

Pete Parry came to Moab in 1975. His Park Service career had begun in the late 40s when he took a seasonal job at Grand Teton National Park. Pete recalls, “I never considered working anywhere else. I liked what the Park Service did. I liked who they were…and besides I met my wife in the Park Service.” He and Joyce met at Natchez Trace in the mid-50s and married in 1957.. Less than twenty years later, they found themselves in this remote but controversial part of the Colorado Plateau.

The timing of his arrival could not have been more significant— SE Utah’s national parks were experiencing the most turbulent period in their history. On a wider scale, much of the rural west was in a near state of revolution—for millions of rural westerners, the Sagebrush Rebellion was a serious movement. No place was more divisive or more visibly in revolt than southeast Utah.

Until the 1960s, westerners had, to a great extent, a free run of the public lands that spread almost limitlessly across the west. Environmental restrictions were few and enforcement of what rules did exist was almost non-existent. But the 1964 Wilderness Act began to change all that. The new law called for the establishment of wilderness areas across the country. A decade later, in 1974, the Federal Land Management Policy Act (FLPMA) was introduced in Congress and enacted into law two years later. FLPMA created the mechanisms to find and designate wilderness. It also provided a new set of regulations and proposals for the management and use of federal lands across the country. These new laws were handed to the agency in charge, the Bureau of Land Management (BLM). In addition to a wilderness inventory, new mining and grazing rules were established, road rights-of-way were scrutinized. And for the first time, a serious effort to enforce these regulations was put in motion. The politics of the West would never be the same again.

At BLM’s Moab office, district manager Gene Day attempted to steer the agency and rural Utah into this new age, but his efforts were doomed from the start. After a century of laissez-faire treatment from the feds, BLM’s new high profile restrictions set poorly with the populace. Fighting back, the county commissioners in SE Utah, according to writer Ray Wheeler, “had a strategy that offered the elegant simplicity of a sumo wrestling match.” When they didn’t like a new rule, they simply disobeyed it, encouraging their constituents to do likewise. When a local canyon was closed to vehicular traffic in 1979, the county fired up its bulldozer and opened it back up again. The BLM got a court order, the county ignored it. On July 4, 1980, county commissioner Ray Tibbetts manned the D9 Cat himself and tore down the BLM blockade.

Manager Day lashed back, attacking the local politicians and their followers in the local paper. The Washington Post wrote a piece about the uprising and identified gen day as “The Most Hated Man in Southern Utah.” Eventually he was transferred .

Into this fever-pitched battle came Pete Parry. As Pete says, “I had no idea what I was walking into.” While much of the anger was aimed at the Park Service’s federal cousins at the BLM, the NPS faced challenges of its own. Pete took the reins at Canyonlands in mid-1975. He arrived in Moab at a time when attitudes toward the parks and the environment were changing nationally.

National Parks had always been developed with an eye to accommodate the greatest number of visitors. It was, for many park managers and for the agency, a measure of success. A park that failed to show steady annual increases in park visitation had a problem and efforts to boost tourism were encouraged. Parks became known more for their spectacular paved roads and lodges than their scenery. But in the 70s, as environmental issues became more prominent and as efforts to preserve parks in a more pristine state were embraced, the Park Service began to re-evaluate its objectives. At Canyonlands, that was a problem.

Canyonlands National Park had been established barely a decade earlier, in 1964, in part due to the efforts and influence of Bates Wilson, the first superintendent of Canyonlands and a lifelong booster of Southeast Utah. Bates, through sheer will of his personality, established a personal friendship with then-Secretary of Interior Stewart Udall in the early 60s. After countless pack trips and Washington visits, Canyonlands National Park was established by an act of Congress. The compromise bill created a park of 257,640 acres and was expanded in 1971 to 337,570 acres, or 527 square miles.

Local opposition to the new park had been fierce—ranchers and miners feared a national park would severely limit grazing and mineral extraction and the community feared such restrictions would adversely affect their economy. The Park Service presented a development plan that called for major developments at both the Needles District and in the Island in the Sky sections of the park, complete with scores of miles of paved roads, loop tours and on-site tourist developments like lodges and cafes. In addition, a massive scenic highway along the west side of Canyonlands, all the way to the upper reaches of the Grand Canyon was proposed and under serious consideration. With some reservations even Bates Wilson supported the new tourist highway. Grand and San Juan Counties accepted the park plans with a grain of salt but embraced the plans for a high profile park that called for dramatic increases in tourism. The local businesses prepared for the changes and the crowds. But neither came.

A decade after the park was established, few changes had occurred. The Island in the Sky was still reached by dirt road and the Needles pavement ended at the district “visitor center,” a surplus tin trailer that the park had acquired at a government surplus auction. The remoteness of the Canyonlands was intact, and to the business community, its continued isolation and lack of amenities was the betrayal of a promise.

By 1976, Grand and San Juan Counties demanded action. In November, Utah’s only (and last) Democratic senator, Frank Moss, was defeated by newcomer Orrin Hatch and congressional pressure to force massive development at Canyonlands intensified. Pete walked into the middle of all this, aware that when he arrived, “there was no General Management Plan at all for the park. There was nothing.”

Canyonlands was adrift, with extreme pressure from local and state politicians to embrace big money and big roads and, in the process, transform one of the most remote and pristine places in North America. It would have been easier, in the political climate of the time, to either support the expansion of roads and amenities, or at least take a bystander’s role, but he didn’t. Pete had to choose between the future and the past. He opted for the future.

While many Utahns blamed the lack of development on an obstructionist agency, few wanted to acknowledge that, in fact, the world was changing. A greater environmental awareness was replacing the growth at full-speed mentality of the post-war era. For the first time in its history, the National Park Service paused to re-evaluate its dual mandate. For daces the NPS had pursued two often conflicting goals, “to preserve and protect” national parklands, and “to provide for the enjoyment of the people.” Clearly the two stated objectives were at crossed swords with each other. Until now, the “enjoyment” trumped the “preservation” almost every time they were put to the test. But now, more Americans weren’t so sure they wanted paved roads and concession stands cutting the park to pieces in the process.

For the next several years, Pete moved quietly, and occasionally not that quietly, but deliberately to include a scaled back option. The NPS offered the possibility of Canyonlands as a “backcountry” park. That management plan alternative proposed a limited park roads system that would scrap plans for the “Kigalia Highway,” the dream project of San Juan County Commissioner Cal Black. Black’s plan was to build a 40 mile highway that would wind its way out of the park via Bobby’s Hole to Elk Ridge, then pass between the Bears Ears and descend to its junction with Utah Highway 95 at Natural Bridges National Monument. Pete agreed to a short extension of the paved road to the edge of Big Spring Canyon, but as far as Parry was concerned, the road ended there. Cal Black called it the Road to Nowhere.. (In 1975 Cal would become the basis for the character ‘Bishop Love’ in Ed Abbey’s novel, ‘The Monkey Wrench Gang.’).

Public hearings were held in Denver, Salt Lake City, Phoenix, Moab and Blanding, Utah. Support for the backcountry park vision received enthusiastic support from citizens in the larger cities and split evenly in Moab. Only in Blanding was public sentiment still strongly opposed to scaling back the development of the park.

And Commissioner Cal Black was furious. So were, almost unanimously, the Grand and San Juan Commissions in their entirety. Pete could not recount the number of times he and Black squared off, but it was more times than he could count. He once found himself confronted by both Cal and Reagan’s Interior Secretary James Watt as they did an all day flyover of the park. “It was a very long day,” Pete recalled. “Besides,” Pete added, “I could never understand why Cal wanted that road so badly. Just look at the map. If tourists left the Needles by way of his Kigalia Highway, they would have bypassed both Monticello and Blanding and all the businesses that would have benefitted from the tourist traffic. It made no sense.” It was also why Parry avoided the construction of amenities inside the park as well. He got very little argument from the Chambers of Commerce on that point.

Still the war of words and roads continued. He found himself confronted in his office one day by Congressman Gunn  McKay who demanded Pete submit to the demands of his local constituents. In a voice that could be heard throughout headquarters, Rep McKay bellowed, “I’ll have your job for this!.” Pete, always the master of understatement replied softly, “You’re welcome to try.” Two years later, McKay was defeated for re-election, though it was hardly the kind of defeat most environmentalists cheered. His opponent was Jim Hansen, who would become an anti-wilderness fixture in Congress for the next 20 years.

McKay who demanded Pete submit to the demands of his local constituents. In a voice that could be heard throughout headquarters, Rep McKay bellowed, “I’ll have your job for this!.” Pete, always the master of understatement replied softly, “You’re welcome to try.” Two years later, McKay was defeated for re-election, though it was hardly the kind of defeat most environmentalists cheered. His opponent was Jim Hansen, who would become an anti-wilderness fixture in Congress for the next 20 years.

Meanwhile, Pete avoided the distractions when he could and moved forward. He resisted the paving of the Island in the Sky roads and came up with a novel alternative to pavement. He noticed that the park trail crews used a material called “soil cement”–the crew mixed the local soil with cement to create a hard, non-dusty surface for the walking trails. Pete wondered if it might work on vehicular surfaces as well and for two years, a test patch of soil cement was laid down on the Delicate Arch road at Arches. Unfortunately, the soil cement didn’t hold up as well as many had hoped and Pete was forced to consider paving at least part of the Island.

Some kind of compromise was inevitable. The road was paved to Grandview Point but along much narrower rights-of-way than had been originally proposed. And where the old dirt road wound left and right, Pete insisted that the new road follow the same alignment. For the modern traveler who passes through Gray’s Pasture on his way to the Green River Overlook and encounters a series of tight curves, those are Pete’s handiwork. I still think the NPS should place a sign there that reads: “PETE’S CURVES.” It sure slows down the high speed traffic.

The Plan was implemented over the next decade. And as Pete says, “A quarter century later, that General Management Plan is still in place and essentially untouched..”

But there was scarcely time to appreciate the accomplishment. In the late 70s, rumors circulated in Moab that the Department of Energy (DOE) was seriously pursuing a location for the long-term storage of the country’s high level nuclear waste. Locations adjacent to Arches and Canyonlands National Parks were rated among the top choices for the nation’s first nuclear repository. The plan was to hollow out huge caverns from the massive salt domes that lay thousands of feet beneath the surface in southern Utah, but after preliminary tests, the Arches site was deemed too unstable. DOE officials were disappointed because logistically the location was perfect–it was less than five miles from a major rail line and Interstate 70.

The other sites, near the Canyonlands boundary in the Needles would be difficult to access. But DOE moved ahead with its tests and plans were announced to build a railroad spur from Moab to the site, via the table lands above the Colorado River in Lockhart Basin. One of the sites eventually became a top 3 finalist.

Pete caught wind of the giant project long before the public did. In the beginning, his concerns were not shared by the Park Service at the regional office and so Pete pursued information on his own, With resource management specialist Kate Kitchell, Pete regularly attended quarterly meetings of the DOE in Columbus, Ohio. “We were there just to gather information, “ Pete explained, “so that when the right time came along, we’d be ready.” Eventually, the NPS did see the threat and Pete became the Park Service point man.

Again Pete found himself and the park at odds with the local population. By 1982, the economy was sputtering, the Atlas uranium mill was a year from shutting down, and locals, desperate for a new economy to replace the one that was dying saw the repository as a godsend. They saw jobs, regardless of the environmental threats. A straw poll vote showed that almost two-thirds of Grand County citizens supported the repository. Commissioner ray Tibbetts argued that, since uranium was mined and milled in southern Utah, its citizens should be willing to accept the waste as well.

(For a great story on the waste repository and the controversy it generated, read this 1982 Deseret News piece by Joe Bauman.)

Armed with a stunning amount of information, Parry worked to gain the support of the predominantly Republican Utah congressional delegation and the State of Utah. “We ran VIP river trips a couple times a year,” Pete recalled, “and when the elected officials couldn’t come along, we’d always invite one of their staff members. In ways it was easier to talk to them and gain their support. Their recommendations were usually given serious consideration.”

In 1985, comments for the Draft Environmental Assessment were submitted to DOE for consideration. (Here are links to comments from the Interior Department and the State of Utah:)

http://pbadupws.nrc.gov/docs/

http://pbadupws.nrc.gov/docs/

Later that year, President Reagan announced that three sites, at Yucca Mountain, Nevada, Hanford, Washington, and Deaf Smith County, Texas, were still under consideration and in 1987, the DOE chose Yucca Mountain as its final choice. Almost 30 years later, the Yucca Mountain site is still being debated and the country’s growing pile of high level waste remains in “temporary” storage at various locations around the country. But…Canyonlands was out of the competition. Pete’s years of hard work and gentle persuasion had paid off.

Pete retired from the Park Service in 1987. He and Joyce continued to live in Moab, in the same home they bought when they arrived in Moab a decade earlier. They both stayed active. Pete worked with his former political rival, Ray Tibbetts to create the “multi-agency information center” in downtown Moab. Instead of a mini-mall or another fast-food chain, the center of Moab, Utah is now a shady green visitor center, in part, thanks to Pete.

And Pete publicly expressed alarm and offered a warning when the Bush Administration demanded “loyalty oaths” from its employees. In 2006, Pete wrote:

“Gone will be the days when the upper management of this nation’s parks made decisions that were best for the parks and their visitors, not for the political party currently in Washington. Now, the political creep is moving down into the working ranks. A long-held ethic of good, science-based decisions will be overturned for politically expedient solutions that last only until the results of the next election. The National Park Service’s mandate “to preserve and protect… for future generations” has no chance to succeed if civil servants swear to say yes to every political whim.”

Joyce stayed busy with the League of Women Voters and for years served as director and co-director of the Moab Valley Voices. When Joyce died in December 2010, she and Pete had been married 53 years and had seen and served the country, from its most beautiful locations—from Natchez Trace to Isle Royal to Great Basin to Joshua Tree to Washington DC to Moab. It was a spectacular journey.

From my own perspective, I’ll always be grateful for the big decisions Pete made, the ones that affected all of our lives for years and decades to come. What would Canyonlands National Park look like today, had Pete Parry not been there to slow down the development juggernaut that, at the time, seemed unstoppable? For many of us, much of the SE Utah/Moab “Scene” has in the 21st Century become the thing Pete detested the most–the Disneyfication of a natural area. Canyonlands, with its limited tourist infra-structure, remains a haven from much of that madness.

And imagine a nuclear waste repository, just a couple thousand yards from a national park boundary. Imagine a new 27 mile highway and a 37 mile train carrying millions of tons of nuclear waste, 24 hours a day, for decades. THAT is what Pete Parry helped stop.

Those are the BIG things. But for me, I will also cherish the little gestures as well—the way I could stop by his office and always get a friendly hello. “Have a seat,” Pete used to say with a chuckle. “What kind of trouble have you got us into now?” He was always patient. He always gave good advice. And best of all, I always thought he gave a damn.

Quiet integrity…that’s Pete Parry.

To read the PDF version of this article, click here and here.

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!