How Silence & Tranquility Became Antiquated Notions in the Brave New West…

I would rather sit on a pumpkin and have it all to myself, than be crowded on a velvet cushion. ~Henry David Thoreau

When Thomas Jefferson purchased the vast territory of Louisiana from France in 1803 and sent Meriwether Lewis and William Clark to explore it, he had no idea just how vast and seemingly unlimited his new acquisition was. They left the known world in May 1804 and traveled up the Missouri River to its headwaters, crossed the Rocky Mountains and descended to the Snake and Columbia Rivers. The long and arduous journey eventually brought them to the Pacific Ocean. All this and their expedition was only half over. They would not return to the capital and Jefferson until September 1806.

Throughout those two long years, Jefferson could do little but speculate about the journey. Only after their return did he begin to grasp the magnitude of his Purchase. The President listened enthusiastically to their extraordinary trip narrative. When he had heard it all, Jefferson concluded that the North American continent was much larger and more imposing than he had imagined. He proclaimed that it would take “a thousand years” to settle the country. Perhaps more.

Jefferson was a brilliant man but this prediction missed the mark.

“Settlement” of the American West, from the Great Plains to the Pacific Coast did not begin in earnest until the late 1840s. The Gold Rush in 1849, the remarkable movement of Americans to the West in search of free land via the Homestead Act, and the construction of the Transcontinental Railroad transformed the continent.

Towns and cities grew overnight and in the process, hundreds of thousands of Native Americans were killed or dispossessed of their land and their homes. Incalculable numbers of animals were driven to or near extinction, including the American Bison which had boasted a continental population of 50 million in 1850. By 1893, fewer than 200 could be found by scientists in search of remnant herds.

The historian Frederick Jackson Turner proclaimed in 1893 that the “frontier was closed.” He explained that the development of the frontier, “begins with the Indian and the hunter; it goes on with the disintegration of savagery by the entrance of the trader… the pastoral stage in ranch life; the exploitation of the soil by the raising of unrotated crops of corn and wheat in sparsely settled farm communities; the intensive culture of the denser farm settlement; and finally the manufacturing organization with the city and the factory system.”

It was over. The continent was beginning to fill and only a few realized what was being lost. Most of us rarely miss what’s being taken until it’s gone and so it was with the open spaces and the wide vistas of the West.

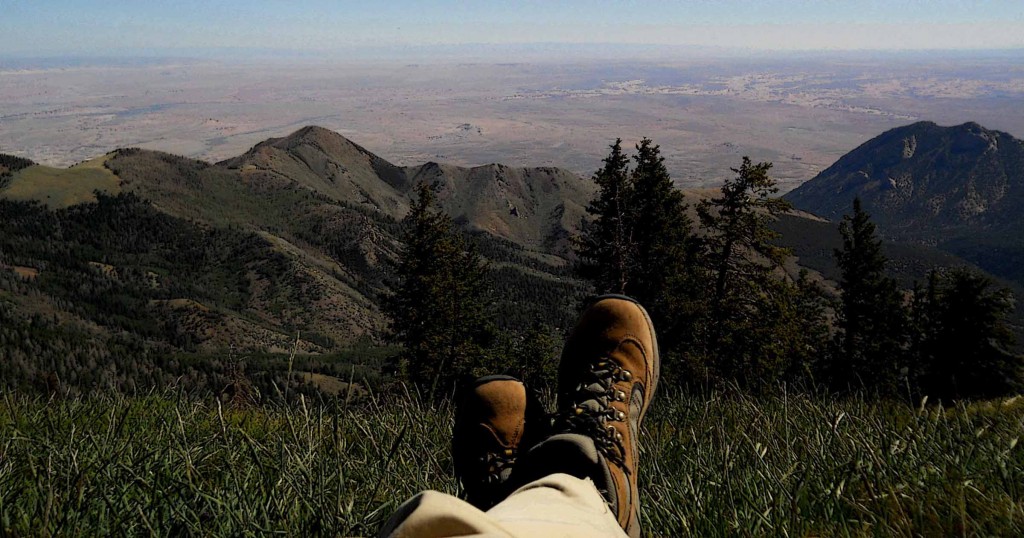

Within the dwindling landscape, some saw for the first time the degradation of aspects more difficult to define–those intangible qualities that are more a consequence of the land than a physical part of them. All of that empty space brought a great silence. To many it was intimidating and even frightening and the cities they built to escape it were the refuge, not the haven. But for some, there has always been an almost primal need for the quiet that offered tranquility instead of fear. There was a word for it—solitude.

Within the dwindling landscape, some saw for the first time the degradation of aspects more difficult to define–those intangible qualities that are more a consequence of the land than a physical part of them. All of that empty space brought a great silence. To many it was intimidating and even frightening and the cities they built to escape it were the refuge, not the haven. But for some, there has always been an almost primal need for the quiet that offered tranquility instead of fear. There was a word for it—solitude.

Solitude has been pursued by those who longed for it in whatever place they found themselves. Thoreau noted, “I never found the companion that was so companionable as solitude. We are for the most part more lonely when we go abroad among men than when we stay in our chambers.”

And Edna LeShan observed, “When we cannot bear to be alone, it means we do not properly value the only companion we will have from birth to death – ourselves.”

Solitude can be a struggle. The French novelist Sidonie-Gabrielle Colette confessed that, “There are days when solitude is a heady wine that intoxicates you with freedom, others when it is a bitter tonic, and still others when it is a poison that makes you beat your head against the wall.”

But the great English diplomat and Nobel Peace Prize recipient Robert Cecil insisted, “Solitude shows us what should be; society shows us what we are.”

Nowhere has solitude been more keenly felt than in the enormous emptiness of the American West. The naturalist John Muir first articulated the feeling that so many of us would pursue in the next century. He wrote:

Muir founded the Sierra Club and devoted the rest of his life to saving the wild places he saw threatened. He won a great victory when the Yosemite Valley was protected from exploitation but grieved to his dying day when another remarkable place, Hetch Hetchy, was drowned by a municipal reservoir. He loved the natural world with a passion that is almost unknown now. And he longed for solitude. “Only by going alone in silence,” he urged, “without baggage, can one truly get into the heart of the wilderness. All other travel is mere dust and hotels and baggage and chatter.”

Since then, other voices for solitude have articulated the yearnings of succeeding generations. Aldo Leopold wrote, “To what avail are 40 freedoms without a blank spot on the map?” And he warned most prophetically, in ways he may not have even realized at the time, “Civilization has so cluttered this elemental man-earth relationship with gadgets and middlemen that awareness of it is growing dim.”

For my generation, Edward Abbey crystalized vague, undefined emotions about the land that we struggled to articulate. Desert Solitaire embraced both physical wilderness and solitude and fused them. For us, the two components were inseparable. I remember a particular passage:

” … the air is untroubled, and I become aware for the first time today of the immense silence in which I am lost. Not a silence so much as a great stillness – for there are a few sounds: the creak of some bird in a juniper tree, an eddy of wind which passes and fades like a sigh, the ticking of the watch on my wrist – slight noises which break the sensation of absolute silence but at the same time exaggerate my sense of the surrounding, overwhelming peace. A suspension of time, a continuous present. If I look at the small device strapped to my wrist, the numbers, even the sweeping second hand, seem meaningless, almost ridiculous.”Abbey reveled in his solitude. “I am twenty miles or more from the nearest fellow human, but instead of loneliness I feel loveliness. Loveliness and a quiet exhultation.”

Indeed, three years before Desert Solitaire was published, the United States Congress, in a rare display of vision and selflessness, passed the Wilderness Act of 1964. Not since the federal government established the idea of national parks, almost a century before, had it exhibited the foresight to preserve lands that might someday be compromised or lost. According to the act, wilderness was defined to mean an area of undeveloped Federal land, at least 5000 acres in size, that “still retained its primeval character and influence, without permanent improvements or human habitation.”

And…just as significantly, offered “outstanding opportunities for solitude or a primitive and unconfined type of recreation.” In the eyes of the law, ‘solitude’ carried just as much significance as the resource itself. One component of wilderness could not survive without the other. Solitude lost was wilderness destroyed.

This is the way it would always be, I thought. As environmental battles heated up in the 1970s and 1980s, the fight for the preservation of western lands was always waged on behalf of those qualities that defined wilderness itself. We fought for the land and the air and the water and if we benefitted from its protection, it was a side-effect. We didn’t need to add anything to make wilderness better. We didn’t need to create solitude. It was already there. We simply chose to appreciate the gift.

This is the way it would always be, I thought. As environmental battles heated up in the 1970s and 1980s, the fight for the preservation of western lands was always waged on behalf of those qualities that defined wilderness itself. We fought for the land and the air and the water and if we benefitted from its protection, it was a side-effect. We didn’t need to add anything to make wilderness better. We didn’t need to create solitude. It was already there. We simply chose to appreciate the gift.

Nowhere in the legislation, nor in the hearts and minds and souls of its strongest proponents, was there any mention of money, or economic benefit, or recreational industries, or outdoor retailers. But in the twenty years since environmentalists turned away from the defense of wilderness in its purest form to a more pragmatic, but degrading, strategy of wilderness for profit, a new generation of Americans has grown apart from values that were once so cherished and revered. Ultimately, in order to “save” wilderness, its very meaning may have been lost.

“When everything is reduced to the mere counter-balancing of economic interests…when Nature has been so subjugated that she has lost all her original forms, what room will there be for virtue? In the mean time, things are going to get very murky.”

Part of the disconnect comes from the sad fact that for the past two decades, fewer children experience any direct contact with Nature. Richard Louv’s book, “Last Child in the Woods: Saving our Children from Nature-Deficit Disorder,” supports the notion that kids no longer have any connection to the natural world or to independent thought for that matter. According to a NY Times article by Bradford McKee, “The days of free-range childhood seem to be over. And parents can now add a new worry to the list of things that make them feel inept: increasingly their children, as Woody Allen might say, are at two with nature.”

Now twenty years later, the Nature-Deficit Generation is coming of age, and their children can’t even hope for an anecdotal connection to a “free-range” life in the woods. The outdoors tradition, passed along from one generation to the next, has been broken. The changes are dramatic. For those that still seek an outdoors experience…it’s not exactly what John Muir had in mind.

Almost a decade ago, I read an article from a group called “Cooperative Ecosystems Studies Units.” According to CESU it is, “a network of cooperative research units (that) has been established to provide research, technical assistance, and education to resource and environmental managers…multiple Federal agencies and universities are among the partners in this program.”

Almost a decade ago, I read an article from a group called “Cooperative Ecosystems Studies Units.” According to CESU it is, “a network of cooperative research units (that) has been established to provide research, technical assistance, and education to resource and environmental managers…multiple Federal agencies and universities are among the partners in this program.”At a CESU gathering called,“Tourism Break-Out,” the group noted that tourism patterns in the West were changing and that it was “important to have young people involved in projects – because they are a group that can help federal agencies recognize future needs.”

They worried about “the changing values of generations regarding parks – what one generation values in a park (such as solitude) may be less important to another generation (that may be more interested in extreme sports).”

Given their mandate to provide for the enjoyment of all people, federal land managers had reason to worry; visitation by people under 30 has been declining steadily for a long time. Rather than seeing this as something of a blessing–after all, their other mandate is to protect the park resources–federal bureaucrats are trying to find incentives that go beyond the beauty of our natural wonders to lure new visitors to them.

The CESU report concluded, “(There is) great potential for partnerships with outdoor recreation outfitters, suppliers, clothing manufacturers, etc., who already know a great deal about our federal land visitors and have a strong handle on how people are using that land.”

CESU’s observations could not have been more telling. Since then, any effort to promote a pro-wilderness/pro-nature experience often embraces high-tech, adrenalin-laced and often high-risk physical activity.

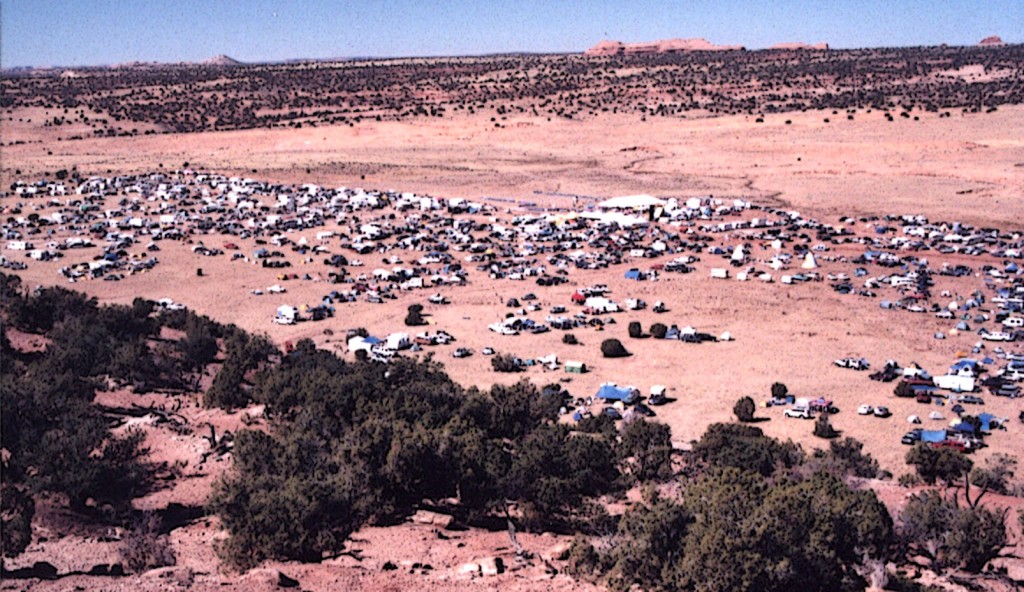

My beloved Moab, Utah, once known for its scenic beauty and as a place to seek solitude and tranquility continues to transform itself, like a Ray Bradbury Martian, trying to please its new guests. Almost overnight it became the “Mountain Bike Capital of the World” and the competition between them and the slow-moving hikers has become a point of contention ever since.

My beloved Moab, Utah, once known for its scenic beauty and as a place to seek solitude and tranquility continues to transform itself, like a Ray Bradbury Martian, trying to please its new guests. Almost overnight it became the “Mountain Bike Capital of the World” and the competition between them and the slow-moving hikers has become a point of contention ever since.But in a nod to the changing needs of national parks and the people who use them, the Park Service recently changed its own rules regarding the use of bicycles in national parks. It “authorizes park superintendents to open existing trails to bicycle use within park units under specific conditions.”

While most parks, including Arches and Canyonlands, have no current intention to change their rules and throw bikers and hikers into a free-for-all, what may happen down the road is anybody’s guess. As today’s young seasonals become tomorrow’s middle managers, those changes may occur.

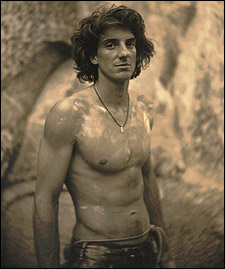

I was livid and snapped off an editorial condemning the self-serving publicity stunt. Some of my readers took angry exception. One young reader wrote, “Dean Potter has raised more awareness about nature and done more for the protection of our wildlife areas than an army of you idiots bitching on the internet will ever do. It’s this geriatric community of do-nothings that wants to sit by and look at rock that is getting butt hurt. It’s so sad, watching you people grow old and bitter, wanting the government to regulate everyone’s lives to suit your tastes.”

Young recreationists like “Seth” look to extreme adventurers like Potter and Slackline King, “Sketchy Andy” Lewis with reverence and adoration. Lewis has drawn world attention with his high wire spectaculars, bouncing precariously on a cable strung hundreds of feet above the ground. He has followers world-wide. They are the heroes of the “environmental movement” in the 21st Century. “Looking at rock” is an antiquated notion.

But it may be possible that “looking at rock” is an acceptable experience if done at high speed. Also coming to Moab is Southeast Utah’s first commercial zipline park on the cliffs north of town, on property once owned by the Uranium King Charlie Steen. His son, Mark, working with Moab’s Casey Bynum is bringing “The Next Big Thrill” to Moab. The course will include seven zip lines of various lengths— from 290 to 1,240 feet over 53 acres. Zipliners will reach breathtaking speeds as they fly down the sandstone cliffs of Moab.Utah Public Radio (UPR) reported the story in December. “Because Moab is known as an ‘adventure town,’ Bynum believes the zip line will fit right in. The town asked for extra engineering studies, but permits were granted with no opposition.”

Even wilderness itself–legislated, congressionally-approved and designated —is changing dramatically, with less chagrin from hikers than one might expect.A study by Troy Hall and David Cole called, “Perceptions, and Behaviors of Recreation Users:

Displacement and Coping in Wilderness,” attempted to determine if accelerated use of wilderness areas was degrading the “wilderness experience” of its users. Their conclusions, based on many interviews and research, surprised even them. They concluded:

“Most visitors perceive adverse changes, such as increased crowding and impact. Majorities reported that these places feel less like wilderness than they did in the past. Most visitors have learned to cope with these adverse changes either by making simple adjustments in their behavior or the way that they think about these places. Consequently, most visitors report that their experiences are largely unchanged and that they are as satisfied with their experiences as ever… few people are absolutely displaced.”

In other words, while backpackers and hikers might have preferred more solitude, it was no longer a make-or-break issue. The one proposal that brought stiff resistance was restricting access to reduce numbers. Nobody wanted that.

A story by Heather Hansen at ‘High Country News’ reported that, “Another recent study based on users of the Alpine Lakes Wilderness in Washington and Oregon’s Three Sisters Wilderness, looked at what factors most detracted from visitors’ having a ‘real wilderness experience.’ It revealed that while people don’t like to have others camp nearby them in the wilderness, or when strangers walk through their camp, the biggest factor detracting from their experience was seeing litter.”

Near Moab, where use of the once obscure Mill Creek area has exploded and even attracted European tour buses, efforts to maintain its once pristine condition have overwhelmed those trying to protect it. One of my heroes, Sara Melnicoff of Moab Solutions, continues to wage a holy war against the litter and junk dumped daily along the trail. She regularly hauls away truckloads of garbage. And yet, if we take the HCN report to heart, perhaps keeping all that litter on the ground is the best way to stop the exponential increase in visitation. Desperate times call for counter-intuitive solutions.

Near Moab, where use of the once obscure Mill Creek area has exploded and even attracted European tour buses, efforts to maintain its once pristine condition have overwhelmed those trying to protect it. One of my heroes, Sara Melnicoff of Moab Solutions, continues to wage a holy war against the litter and junk dumped daily along the trail. She regularly hauls away truckloads of garbage. And yet, if we take the HCN report to heart, perhaps keeping all that litter on the ground is the best way to stop the exponential increase in visitation. Desperate times call for counter-intuitive solutions. What does the future hold? As energy costs rise and the population swells, can any kind of tourism survive. Many believe it can, and that it will flourish and grow, but their vision insists it will be very different. Mass transit systems, shuttles and a group ethic must prevail. Travelers will no longer be choose from unlimited destinations. The car, that same contraption that is suffocating the planet, gave us limitless options and unbounded mobility. Tourists of the future will lose that; instead they can expect the option of numerous “natural” and “recreational” experiences. Or as the marketing brochure will insist—a perfectly blended mix of both.

What does the future hold? As energy costs rise and the population swells, can any kind of tourism survive. Many believe it can, and that it will flourish and grow, but their vision insists it will be very different. Mass transit systems, shuttles and a group ethic must prevail. Travelers will no longer be choose from unlimited destinations. The car, that same contraption that is suffocating the planet, gave us limitless options and unbounded mobility. Tourists of the future will lose that; instead they can expect the option of numerous “natural” and “recreational” experiences. Or as the marketing brochure will insist—a perfectly blended mix of both.

They’ll be shuttled to motels and “adventure” centers. They’ll ride a bus to biking or hiking trailheads. They’ll subsequently need to travel in groups. They can disperse if they like, but in wild new territory, unfamiliar to newcomers, there is safety in numbers. They’ll be dropped off at designated times and picked up at designated times. And at designated locations.

A certain amount of regimentation will be inevitable for mass transit and regional shuttles to operate on such a vast scale. In this future, opportunities for solitude survive, but in not quite the same fashion I imagine the meaning of the word to be. Painful to ponder, but as inevitable as sunrise.

What’s notable is that for many travelers to Moab in 2013, the Future is already here. And for them, it doesn’t sound that bad. For a majority, perhaps, it sounds preferable to the kind of wilderness experience and solitude I prefer. And THAT is what people like me need to remember.

Many decades ago, the Sons of the Pioneers wailed…

Everything seems so strange.

Where are the pals I used to ride with?

Gone…to a land…so strange.

It’s a cowboy’s lament. And I realize that this ain’t the same old range either. The world keeps turning over, again and again, faster than any of us dreamed possible. As technology continues to shrink the world, its newer citizens embrace the collective over the solitary. Solitude feels like isolation for many of us in 2013 and it has no place in the Brave New West. We all cherish the shared experience, but there was always a need for the empty room. Now the need recedes. “Rugged Individualism” has been in decline for decades. Now it’s in its death throes.

And so, a lament and a longing for the quiet moment, passed along from generation to generation, from the old to the young, for more than a century, from Thoreau to Muir to Leopold to Abbey ends. The solitude is there, if you know where to look for it, but who’s looking? And who would notice or care if it went away?

Is that a bad thing? Who knows? Maybe not. But Ralph Waldo Emerson once wrote, “Adopt the pace of nature: her secret is patience.”

The world has lost patience with solitude these days. They’ll never know what they threw away.

Good essay Jim. I think part of the problem is not only alienation from the natural world, but people’s inability to slow down. I guess that’s not too surprising since most people now seem to be living a “24/7” life. When I see people mountain biking on trails, for example, they always seem to be in a hurry. They can’t possibly have much awareness of the details of their surroundings as they rush by. Do they care about the natural world? Probably not the way I do. As an amateur naturalist I know that patience and stillness are required to see most of the incredible richness and complexity that is present in any natural environment.

I continue to be horrified at the inability of the average American to appreciate silence and solitude. Even when I’m far off the beaten path I can often hear the nearby whine of dirt bikes and ATVs illegally invading wilderness areas. Because there are no effective safeguards for our wild lands, idiots trespass on these places with all manner of proscribed machinery.

Great article. As an avid Abbey and Muir reader high in the mountaintops it was great to hear your perspective. I am a young person who enjoys going tramping (hiking?) and pondering my way along the track. Don’t despair that young people will not find their way. We hear the call of the mountains.

A good article, recreation is an important component of managing natural lands, but it is also a precarious balancing act to keep many user groups happy (let alone the ecosystem functioning).

Unfortunately, I felt the article engages in a lot of unwarranted generalizing. The climbing community roundly criticized Dean Potter for his delicate arch solo (many sponsors dropped him). Also, many climbers are just as interested in solitude as backpackers are, and these groups aren’t exclusive. I for one do both, and I also drive my friends crazy by stopping on the trail to botanize.

Have you ever seen a herd of 30+ PCT hikers come barreling down a trail in the backcountry of the Sierra Nevadas? All wilderness users have impacts, picking groups to antagonize (andrenaline junkies? Really? No climbers I know are into it for some kind of thrill fix) will not help us find solutions.

Well okay, picking on ATV/Dirtbikers is fine

I knew we lost our perspective when friends made a goal to bike the White Rim Trail in one day. There are two dozen places where I could sit on the rim for an entire day or two. Now its just “century” to be bagged. Sad.

Meh. Lots of folks getting out and finding solitude, they just don’t write books, blog, upload to Farcebook or get interviewed (getting interviewed would screw my solitude). They get out and STFU about it. It is after all a finite resource, much more so than when Abbey could indulge himself and make a buck writing about it. Do we really want everyone looking for solitude? Won’t work. Another bitch catch 22 in the old west.

There are still places where solitude is to be found… just don’t talk about them… and if I catch someone talking about them publicly, you’ll find out my attitude about gun culture. I’m serious about Wilderness… and limitations on visitation. Only those who can, should be there. No SPOT, no satellite phones, no instant rescue.