NOTE: Bolded passages are those cut out of the final BIKE magazine article.

When everything is reduced to the mere counter-balancing of economic interests…when Nature has been so subjugated that she has lost all her original forms, what room will there be for virtue? In the mean time, things are going to get very murky. — Gustave Flaubert

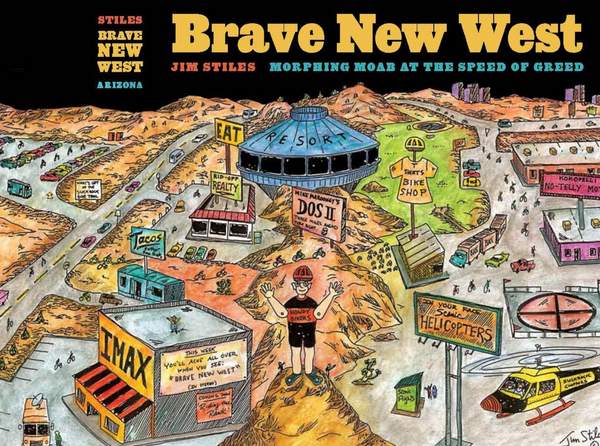

Welcome to Moab, Utah, the “Mountain Bike Capital of the World. Adventure Vortex of the Universe! The Adrenalin Junkie’s Dream Destination! Wanna a take a ride? We’re spending millions to make your biking experience more pleasurable.

Check out our new “Elevated Colorado River Bikeway.” Our cantilevered concrete and steel bike bridge parallels the river for miles. “It’s a new way to experience the river,” its promoters exclaim, as if the “old way” didn’t cut it any more. Need a break from the bike? We have zip lines and slack lines and you can harness up and rope swing through Corona Arch. “Adventure” activities are everywhere. Need to shop?. We’ve got T-shirts and refrigerator magnets to die for. Moab, Utah is booming. Is that a good thing? Do you like Disneyland?

Moab has always been a boom—and bust—kind of town. Tucked away in the labyrinth of red rock canyons and mesas, it might have become the perfect refuge from the madness of the world, instead of a symbol of it. In its early years, Moab was noted for its orchards and alfalfa fields and watermelon patches. A tranquil disconnect from the ‘real world.’

But Moab always had its dreamers and schemers. Decades ago, the exploitation of natural resources fueled visions of glory and wealth. When a bookish geologist named Charlie Steen found uranium where it shouldn’t exist, he ignited the biggest boom in history. Thousands of instant prospectors descended on the once empty Four Corners region. Moab grew ten fold.

The uranium industry stayed strong through the 70s. But then came Three Mile Island and Chernoble and falling ore prices. By 1987, Moab’s economy hit rock bottom. Unemployment reached 20%. Empty homes were everywhere. Some thought Moab might dry up and blow away.

Moab’s Old Guard turned to any project they thought might revive the economy. They even pushed for a toxic waste incinerator but burning toxins failed to garner much support. That same autumn, a small article appeared in the local newspaper. It read: “Mountain biking in SE Utah is becoming a popular sport.” Hardly anybody noticed.

But two brothers, laid off in the uranium collapse, had an idea. Bill and Robin Groff opened a bike shop, Rim Cyclery, and started testing their pedal-powered Stumpjumpers on the rugged sandstone terrain. The following spring, National Geographic came to Moab, shooting images of the red rocks and the photographer took note of the bicyclists. When the story appeared, Hank Barlow was impressed. A Marin County native (the Birthplace of Mountain Biking), Barlow had imagined creating a magazine exclusively about mountain biking and wanted something extraordinary for its premiere issue. This was it.

But two brothers, laid off in the uranium collapse, had an idea. Bill and Robin Groff opened a bike shop, Rim Cyclery, and started testing their pedal-powered Stumpjumpers on the rugged sandstone terrain. The following spring, National Geographic came to Moab, shooting images of the red rocks and the photographer took note of the bicyclists. When the story appeared, Hank Barlow was impressed. A Marin County native (the Birthplace of Mountain Biking), Barlow had imagined creating a magazine exclusively about mountain biking and wanted something extraordinary for its premiere issue. This was it.

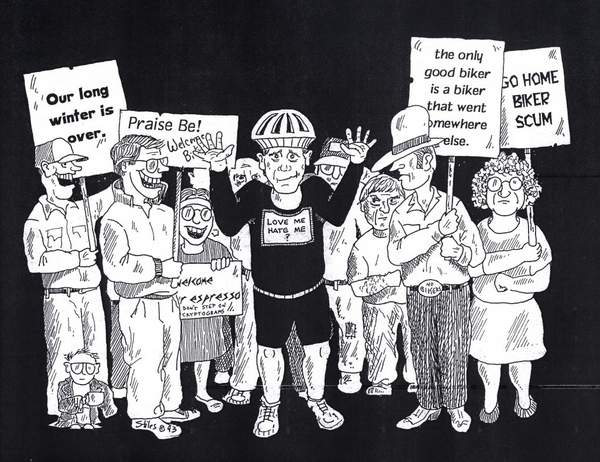

After that, everything changed. At first it was simply the culture shock. Lycra hadn’t made its way to Moab—some thought we’d been invaded by wheeled naked blue people. There was the inevitable clash with Old Moab—pickup trucks with teenaged rednecks swerved and sweared as they passed the hapless bicyclists. A few fights broke out, but the negative sentiments were more bark than bike. The truth was, Moab suffered from severe economic depression and its residents were desperate.

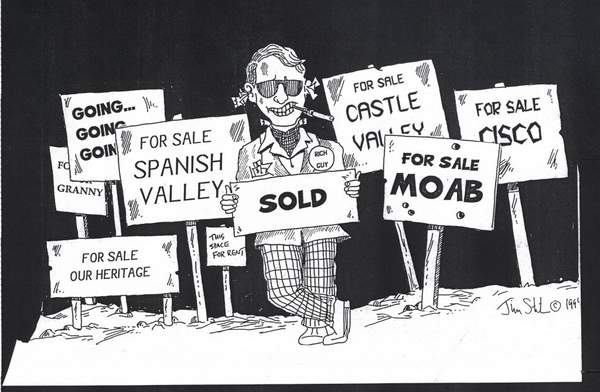

We were easy pickins. The vanguard of bikers came from places like California and Colorado, young urban professionals, affluent, and always in search of a good investment. Few could miss the plethora of “for sale” signs that lined residential streets. Inevitably a curious biker called a realtor and inquired about prices. Whoever it was must have been dumbstruck. Every home imaginable was available, but a house that sold for $50,000 five years earlier could now be had for half. Word spread like ticks on a reservation dog.

It became a joke. Tourists who traveled here to experience a new sport on some unique terrain left Moab days later as new homeowners. And they rarely bought just one; they simply couldn’t resist a great deal. Even a few realtors were offended. “They’d arrive with their checkbooks and ask, ‘What can we steal today?’” A Four-fer could be bought for under $100,000

By 1990 the sea of ‘for sale’ signs faded. But many of the recently purchased houses remained empty. The new owners hired property managers and waited for the market to drive prices up. It was a pork belly housing boom. An absentee “neighbor” put a $70,000 price tag on his $25,000 cinder block shed. Even the realtors urged their clients to show restraint. But the new owners knew more than the professionals. They’d bought the homes outright. They’d simply wait for the market to come to them. A year later, the cinder-block shed owner got his asking price (In 2013 it would fetch $250,000). Moab’s cachet as a New West town grew legs.

Moab was now Mountain Bike Capital of the World and the development of residential housing projects accelerated. Ground was broken on a multitude of condo developments. They had such lovely names: Solano Vilejo….Mill Creek Pueblos….Coyote Run…Orchard Villa.

“Daddy, why do they call our home ‘Orchard Villa?’”

“Because, son, there used to be an orchard here.”

(Long pause) “Daddy…what’s an orchard?”

Main Street was transformed as well. Out of town investors, especially from Park City, Utah, saw an opportunity to buy much of the commercial downtown area. Boutiques and T-shirt shops sprouted everywhere. Two of Moab’s three local greasy spoon cafes went belly up and national fast food franchises took their place. The Atomic Motel became the Kokopelli Inn.

The economy boomed, but for whom? As Moab gained cachet, immigrant speculators, better financed to exploit the boom, flooded Moab. They opened competing businesses, and home-grown owners felt the pinch. When growing numbers of restaurants, for example, outpaced tourist visitation, businesses saw their slice of the economic pie shrink. But the new arrivals were better equipped to ride out the slowdown. With the Millennium, Moab scarcely resembled its old self. Even tourists complained that Moab was losing its “funky charm.” Other towns, like Fruita, Colorado and Sedona, Arizona, tried to wrestle the “Capital” claim from its Utah cousin.

Now Moab’s recreation-based business leaders and politicians sought to further transform Southeast Utah and reclaim its crown. In some cases, the biker-based business leaders became the politicians in the early 2000s.

Kim Schappert, had come to Moab in the late 80s with then-husband Hank Barlow. Remember Hank? He

put Moab on the map when he created and published “Mountain Bike.” Now Schappert was ready to go further. Invested in a local bike shop and elected to the Grand County Council, Schappert relentlessly pursued her vision to create a vast network of single-track trails throughout public lands near Moab. An advisory committee, Trail Mix, and later Moab Trails Alliance, with Schappert at the helm, worked with various federal and state agencies like the Forest Service, BLM, the Park Service, and the State Lands Trust. Cultivating connections at the state and federal level, the ambitious and aggressive Schappert was wildly successful.

Critics complained there were plenty of available trails–particularly those jeep roads from the 50s. But now, with little opposition, enthusiasts began cutting scores of miles of new single-track. Grand County Councilman Chris Baird explained, “Without developed trails our recreational assets would be limited to river running and scenic driving…trails form the backbone of the recreational assets that Grand County markets to the world.”

It was about “marketing assets.” And they were good at it. But they weren’t done. The most extravagant component is on the way. Schappert’s “showpiece” is the $20 million “North Moab Recreation Transportation System,” now under construction. A new “Moab Hub” and a three mile “Elevated Bikeway” that parallels the Colorado River will be completed next fall. Its proponents insist that the bikeway is needed for “safety reasons.” But it rang a lot truer when Baird complained, ”we started seeing newspaper and magazine articles about Moab going stale.”

The fear of “going stale” and losing its Money Mojo has fueled Moab’s transformation. The recreation industry completely dominates Moab’s economy now; any expression of dissent is almost traitorous. Years ago, environmental organizations worried about tourist economy impacts. The Grand Canyon Trust’s Bill Hedden once wrote, “Industrial-strength recreation holds more potential to disrupt natural processes on a broad scale than just about anything else.” But now, Utah Greens turn a collective blind-eye to the onslaught. The concrete cantilevered bikeway didn’t even raise an eyebrow. The Kool-Aid has been drunk.

Where will Moab go from here? Probably in the same direction, but more so. More amenities. More promotion. More Disneyesque. Your biking experience will be planned and packaged and marketed and implemented with great efficiency and professionalism, from start to finish. All you’ll have to do is swipe your card. How much “adventure” do you want? What’s your credit limit?

So that’s it. Moab, for many of us, is gone. We don’t really blame the bikes, or even the riders. They are merely conveyors of a consumer culture, driven by an insatiable thirst for the next Big Thing–the next Boom. It’s an American story, repeated again and again. More than a century ago, the writer Henry James could not believe his eyes as he crossed the continent. He wrote:

“You touch the great lonely land, only to plant upon it some ugliness (and), never dreaming of the grace of apology or contrition, you then proceed to brag with a cynicism of your own….I should owe you my grudge for every disfigurement and every violence, for every wound with which you have caused the face of the land to bleed…

“Oh for an unbridgeable abyss or an insuperable mountain.”

In 2013, nothing in Moab is “insuperable” anymore.

To get the “story behind the story,” click here to read Jim Stiles’ “Sanitizing the Truth: How BIKE Magazine Butchered an Honest Tale of Moab’s Last 20 Years.”

To read the PDF version of this article, click here.

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!

What you say here is true and a bitter reality check for many of BIKE’s readership as well as the editors of the magazine. Too bad that Story turned out to be too weak or whatever and the heart of your article was ripped out and dismembered.

As I’m sure you know, Jim, your story was hacked to pieces because what you wrote was threatening to insecure minds. This reflects poorly on them and very well on you.

I liked the article as a whole, but there are some glaring problems. The one that really caught my eye was “more ticks than a reservation dog.” Very racist.

This is a story of progress. Not necessarily on a large scale, but micro, local, and narrow progress. I have read some of stiles stuff, and he is very thoughtful, informative, and entertaining. He’s often exposed the contradictions of progress, and again does so here with a hard shot at Moab right between the eyes. Does he need to remind us in this way of what we already know and have chosen to ignore? I dont know, but I’m glad he does. His thoughtful reflections force us to think harder about the choices in front of us. That’s a good thing that will yield a better future – be it for Moab or anywhere and anything else.

What Bike Mag is most guilty of is missing the point of the original piece. They themselves are simply no more than an appendage of the very industry which has such haphazard transformative powers, and themselves are reliant on being an adjunct method of information sharing to be ran alongside the giant full-color advertizements for bikes that cost as much as brand new cars.

In the eyes of the mountain biking community, I can see why the story of Moab going from a town facing the very real possibility of becoming a ghost town instead becoming a real estate prospector’s dream would be viewed as primarily positive; the outsized corporatization of the town is a side effect of what is going to be viewed as progress from the Lycra clad carbon fiber aficionados who have become heir to the yuppy throne of adventure tourism.

What could have been a more viable focus (only the naive would assume that BikeMag would leave in the paragraphs about how the housing boom came from such abjectly bad circumstances without liberally applying lipstick to that pig) would be on how the local shops wound up getting displaced by the speed of influx from outside commerce activities, and that when people speak of Moab losing it’s charm that it has a large part to do with the local business being cast aside by the outright pace of commercial development.

Why is a magazine that receives subscriptions and has both its best interests and it feels the best interests of Moab by sending more tourist dollars that way going to publish a quote like “So that’s it. Moab, for many of us, is gone.” They aren’t going to, and complaining about an editor wisely doing away with that is stupid – and a large part of how the editorial staff then felt that it was within their proviso to liberally make slashing cuts elsewhere (most of which I too disagree with, and this is why the final piece wound up being a lot of rubbish public relations copy with a thin veneer of the real detail the editor who contacted you wanted), but tailoring more of what you wrote to what they could publish would have preserved a lot more of the voice and message – instead they found themselves obligated to remove a fair bit of the piece (and over-edited from there) and the sort of material they’re going to backfill it with is going to miss the greater message: that is that Moab has the possibility of being more of that unpolished but unashamed gem of a town, but that doing so requires something more than trying to convert it into the red-sandstone arched version of Disneyland, instead of merely grousing about some of the inevitable changes.