It is not that Pueblo Indians hate modern America…It is just that our unchecked growth, lack of social cohesion, and flamboyant use of resources worries them as being unsustainable. They expect to outlast us. – David E. Stuart, Archaeologist

4 a.m. on a December morning, 1989. I drove north out of Tucson, Arizona, whisking through the deserted streets of a small town down the highway and then by a state prison flooded with orange light. My tires whined on U.S. 60 running along the southwestern flank of the Superstition Wilderness, east of metropolitan Phoenix. I spotted a lone gas station and a small Mexican restaurant in a white box building, shut down for the night.

At the western edge of the Wilderness I bumped along a winding road to the deserted First Water Trailhead. Strapping on my backpack in the chilly air, I gazed at the white and gold first light above a black rise in the trail, backed by a mountain’s slender arc. A lone Saguaro stood thin and sharp in the gold sky. The veil of contemplative silence that you find in a Wilderness lay a mile down the trailhead.

At the time the population of nearby Apache Junction, the outlying rim of greater Phoenix, was 18,100.

***

When I spent summers in Tucson in the late 1960s, word was already out about the falling water table in the greater Phoenix area; its population at the time was less than 1,000,000. It meant: too many humans here. You’d think that people living in a Southwestern desert would be acutely aware of the scarcity of water and would have paid attention to this.

But instead they opted for a techno-fix, the Central Arizona Project, a 336 mile system of aqueducts, pipelines, and so forth diverting 1.5 million acre-feet of water from the Colorado River to Phoenix, Tucson, and other localities. Construction was under way by 1973 and it was online by the mid 1980s. With CAP’s help the City of Phoenix cut its reliance on groundwater from 35% in 1984 to 3% in 2008.

It seemed like a good solution at the time.

***

5 a.m. on a March morning, ten years later. I drove a boxy airport rental car onto U.S. 60 as it coalesced into two lanes west of Apache Junction, running along the southwestern flank of the Superstition Wilderness. Same road, same place, opposite direction.

Oncoming headlights whooshed past me in an unremitting stream; it was rush hour from new housing developments near the Wilderness and the explosive population growth in nearby Florence. My shoulders high and tight, I flicked the rental car left between two sets of headlights, careening onto a dark, bumpy road leading to the Wilderness and Peralta Trailhead. The yellow stream of traffic vanished behind me.

The population of Apache Junction was 31,800.

***

A warning that CAP wasn’t the great techno-fix after all came with the arrival of a long-term drought in the late 1990s.

More warnings arrived after that. In 2003 and 2004, for the first time in half a century, the Salt River Project (SRP), which furnishes the City of Phoenix about half of its water from reservoirs on the Salt and Verde Rivers, cut its water deliveries by a third. Phoenix made up for the shortfall in those years by taking extra water from CAP, which furnishes Phoenix about 40% of its water (“Drought in Perspective,” phoenix.gov).

As of 2007 greater Phoenix was getting 60% of its water from CAP and 35% from SRP (“Arizona Would Bear Brunt of Water Restrictions,” findarticles.com).

Another warning was the report, “Climate Change and Water,” issued in June, 2008, by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), an organization too prestigious to ignore. The estimated population of greater Phoenix had grown to 4,282,000. Although the report had a worldwide focus, it drew a bead on the Colorado River Basin: “…the allocation of Colorado River water to basin states [including Arizona] occurred during the wettest period in over 400 years (i.e., 1905-1925). Recently, the Western USA has experienced sustained drought, with 30-40% of the region under severe drought since 1999, and with the lowest 5-year period of Colorado River flow on record occurring from 2000 to 2004. At the same time, the states of the south-west USA are experiencing some of the most rapid growth in the country, with attendant social, economic and environmental demands on water resources…

“…Estimates show that, with increased climatic warming and evaporation, concurrent [water] runoff decreases would reach 30% during the 21st century…Under such conditions, together with projected withdrawals, the requirements of the Colorado River Compact [distributing water among Western states, including Arizona] may only be met 60-75% of the time by 2025…These changes could occur as a consequence of increased temperatures…even if precipitation levels remain fairly constant. Some researchers argue that these assessments, because of model choice, may actually underestimate future declines.

“Most scenarios of Colorado River flow at Lees Ferry (which separates the upper from the lower basin) indicate that, within 20 years, [water] discharge may be insufficient to meet current consumptive water resource demands.” (p. 105).

***

I parked the rental car at the near-empty Peralta trailhead, hoisted on my backpack, and plodded up a low, dark hill. The trail wound along a ridge at the top. As the dawn came I saw that it curved down into a flat valley several miles wide; I looked back at the golden sunlight on the high ridges of the Superstition Mountains. An hour later I walked in the open morning light on the valley floor, ornamented with creosote, red-blooming spires of Ocotillo, and studded with Saguaro cacti.

That’s when I entered the contemplative silence of the Wilderness, which is like a delicate veil about a mile in from the trailhead. The horde of housing developments and the flowing lines of traffic nearby hadn’t yet torn it.

Farther down the trail I dropped my backpack on a flat spot and hung out.

***

That 2008 IPCC report on climate change and water ignited a slow-burning buzz among water professionals in the Southwest because:

- Under the Colorado River Compact Arizona is entitled to 2.8 million acre-feet of water per year, out of a hypothetical annual river flow of 16.4 million acre-feet, which annual flow we now know is artificially high, even without global warming. In time there will be pressure to reduce each state’s share.

- On top of that, 1.7 million acre-feet of Arizona’s current share is “junior water,” meaning that when annual cutbacks in the lower basin from reduced stream flow come, Arizona’s water will be cut back first before any water is cut back from California’s yearly share (4.4 million acre-feet) or Nevada’s (300,000 acre feet).

- Now here’s the kicker. Over time global warming will bring chronically reduced stream flows in both CAP and SRP. What then?Sucking out the remaining water from aquifers isn’t a viable long-term solution, desalinization is expensive (check it out some time), and using stored water and back-up agricultural water are short-term measures. What then?

Still another warning was a 4/20/09 press release, “Climate Change Means Shortfalls in Colorado Water Deliveries,” describing a new study by scientists Tim Barnett and David Pierce: “…if human-caused climate change continues to make the region drier, scheduled [water] deliveries will be missed 60-90 percent of the time by the middle of the century, according to a pair of climate researchers at Scripps Institution of Oceanography, UC San Diego…‘We considered the question: Can the [Colorado] river deliver water at the levels currently scheduled if the climate changes as we expect it to. The answer is no.’” They cautiously addressed changing water use: “In most years, delivery shortfalls will be small enough to manage through conservation and water transfers…But during dry years there is an increasing chance of substantial shortfalls…‘we can avoid such big shortfalls if the river’s users agree on a way to reduce their average water use,’ said Pierce. ‘If we could do that, the system could stay sustainable further into the future…, even if the climate changes.’” The next day a story about the study appeared in The Arizona Republic, greater Phoenix’s newspaper.

Which sure sparked comments on the paper’s website. Between a quarter and a third were at least receptive to the troubling findings and some were insightful. But half or more revealed a disheartening lack of understanding of scientific research or simplistically assumed that a technological fix will come along or reflected denial in some other way. My pick: “These scientists are boneheads…Ninety percent of the earth surface is water. There is no way for it to escape our atmosphere. Therefore we will never run out…it can always be filtered and/or desalinated…we can easily achieve this with Nuclear [sic] power.” A self-revealing statement.

***

That evening I pulled my coat onto my shoulders as the sun dropped behind the rugged backbone of the Superstition Mountains; its corona radiated far above the mountains’ mass. Saguaro cacti thrust up into the twilight like black ICBMs. Afterward the horizon softened and a broad layer of vermillion light overlaid the craggy ridges and the tiny purple outline of a remote mountain range. The sky higher up was gold, arching into soft blue beneath the dark blue night sky.

The next morning, as I drove back toward Apache Junction on U.S. 60, I turned into a housing development along the boundary of the Wilderness. It featured a broad, green golf course encircled by oversized houses. I parked and took a few photographs of the view across one of the greens. The golf course was plainly designed so that the southwestern wall of the gnarled Superstition Mountains would serve as a tame mountain backdrop for a pleasant day of golf. When I developed the pictures back home, they looked like color place mats in a chain restaurant.

***

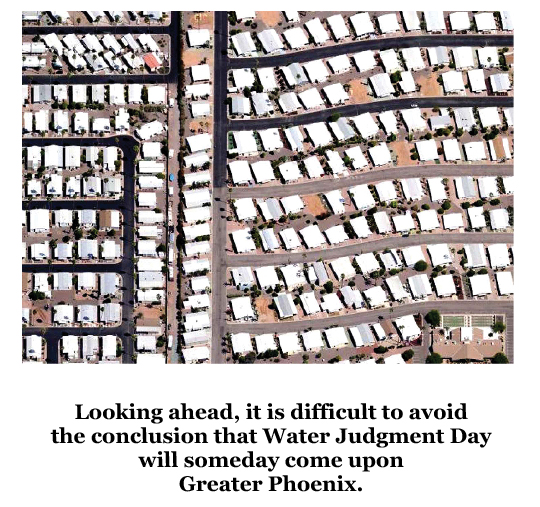

The population growth in greater Phoenix exploded by 590% in the 48 years previous to 2009. Other desert metropolises, although much smaller, showed the same trend: Tucson, up 382%, Albuquerque, up 268%, and Las Vegas, the melanoma of growth, up 1,320%. No one has sized up the compulsive grip of this mindset better than Gary Snyder in a 1976 interview: “…we live in a nation of fossil fuel junkies, very sweet people and the best hearts in the world…who are still caught on the myth of the frontier, the myth of boundless resources and a vision of perpetual materialistic growth.” (The Real Work, p. 69).

To Phoenix and the people who have swarmed there, the mythical “boundless resource,” above and beyond fossil fuels, has been water.

Looking ahead, it is difficult to avoid the conclusion that Water Judgment Day will someday come upon greater Phoenix. It could be that another seeming fix such as buying up agricultural water rights, or even the protracted economic slump, will bail the system out for awhile. But eventually, after a desperate effort to prevent it, the price of water will spiral upward and stay put. The economic juggernaut that was ignited here will not simply slow down. It’ll curve backwards.

I’m not saying Phoenix will become a ghost town. But it’ll be shrunk.

I like to imagine a different story, however. What if, when the water table was dropping in the 1960s, the various metropolitan leaders had planned for their descendants to be living there 500 years in the future? If they had they would have reduced Phoenix to a smaller, stable place in order to protect the water table long-haul, with no Central Arizona Project and no hint of a greed boom. Self-sustaining.

That’s the way the Pueblo Indians think.

***

As I drove out of the housing development I impulsively pulled over to study the pink stone entrance sign. The development’s name, “MEADOWBROOK VILLAGE,” was splayed in outsized brass lettering and a jet of water streamed over a wide stone lip into a five-foot artificial waterfall, filling a concrete pond underneath. The pond was landscaped in front with desert plants.

I stared at the sign and the waterfall.

If I’d somehow asked one of the developers about the ecological significance of the sign and the fake waterfall, she or he might have explained, after a longsuffering eye roll, that they were simple advertising ploys to soothe people shopping for new houses. Because, pause for another longsuffering eye roll, don’t tree huggers like me know that the words “meadow” and “brook” as well as the sight and sound of running water are known to relax people, blah, blah, blah. And might have added that house shoppers either didn’t notice the sign or the waterfall or if they did they didn’t think anything of it.

But I believe that that together they implied, perhaps subconsciously, that home buyers were in a landscape that provided sufficient running water, like the suburbs they’d left behind.

The trouble is that such messages, soothing as they may be, bear no relationship to the landscape. There are no brooks or flowing streams in the Sonoran Desert. An hour’s walk along any trail in the Wilderness, just over the fence line, reveals to any prospective home buyer that in the absence of a thunderstorm the arroyos and washes in this landscape remain dry. To actually have a flowing stream in the Sonoran Desert requires a nearby mountain range that is high enough – 8,000 feet or more – to have a winter snowpack feeding the stream bed melt-water each spring. And even then the stream will likely run dry in the late summer. The Superstition Wilderness, however, tops out at just over 6,000 feet.

At the time I found the fake waterfall, the population of greater Phoenix was up to 3,252,000.

Note: a longer version of this story appeared in the August/September 2009 issue of TheCanyonCountryZephyr.

SCOTT THOMPSON is a regular contributor to the Zephyr.

He lives in Beckley, WV.

To read the PDF version of this article, click here.and here.

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!