Note: This article first appeared in the February/March 2006 edition of the Zephyr.

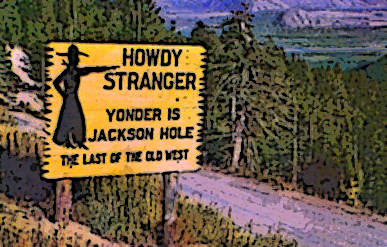

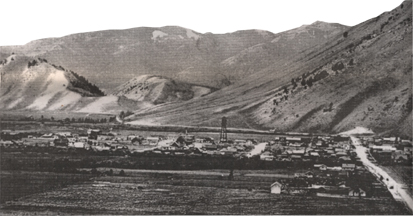

At the crest of Teton Pass there used to be a big wooden sign with a black silhouette of a big-hatted cowboy pointing east into the valley. The sign read: Yonder is Jackson Hole, the Last of the Old West.The sign is no longer there and the valley is no longer the last of the old west. Even back then a more apt “last of the old west” could have been posted outside Elko, Nevada (sheep and cattle ranching), or Kemmerer, Wyoming (coal mining), or Butte, Montana (copper), or many another western settlement.

Our valley got its name from mountain man David Jackson’s preference. His favorite hangout, or so goes the legend. In Jackson’s Hole we were, from nearly the get-go, a mixed economy: dude ranching/cattle ranching. In fact, elite adventurers from Europe toured the west right along with the inrush of land and gold and fur seekers. The first two white settlers in Jackson’s Hole, John Holland and John Carnes, were part-time hunting guides. A ranch on the upper Green river was apparently Wyoming’s first dude ranch, a place for moneyed people to shed some of it. On offer were big-game hunts–elk, deer, bighorns, bears, mountain lions. A pack of lion dogs lived there too.

In a real sense, then, catering to dudes and tending cattle were western founding enterprises. It was commonly understood, at least in Jackson’s Hole, that dudes wintered better. The corollary of that was a quiet, peaceful valley as soon as winter set in, but lively in summer.

One time we were snowed in for a week or ten days, but groceries held out and everyone heated with wood and coal already stored for winter. In one of those isolation periods the editor of the Jackson Hole Courier, Charlie Kratzer, ran out of newsprint. No problem. He went to the grocery store, bought from Butch Lloyd a big roll of butcher paper.

Most families didn’t use Teton Pass much anyway, in winter. If we did, it might be in a canvas covered bob sleigh. I remember one of those journeys. We boarded the sleigh in Victor, Idaho, a Union Pacific spur line terminal. A cold, snowbound day, but the sleigh was equipped with a small coal burner, its stovepipe sticking up through a metal-rimmed hole in the canvas. It drew well. The team, nostrils pushing out frosty air, pulled us up a canyon and a few switchbacks to the top of the pass, arriving at around noon. A roadhouse was there, operated if I remember rightly by the Scott family. We went inside and took our places at one long table and were served a hearty and leisurely meal. Then the descent, the really steep section of the journey, lots of switchbacks, arriving in Wilson at the bottom of the pass well before dark.

There were two schools in town, a two-story brick grade school, eight grades, located near Flat Creek (formerly known as Little Gros Ventre) approximately where a big grassy open space is now, southwest edge of town, and the Jackson-Wilson High school where today’s Snow King ski resort crowds the mountain. Snow King, by the way, was a Chamber of Commerce name, later, when competitive skiing took hold. Before that era, in my memory at least, the mountain is nameless though there was a Kelly Hill, there, a rolling bit of foothill farmed by the Kelly family.

Kids from South Park ranches and the Wilson area came to High School in winter by covered sleigh. Townies walked. We Murie kids had a fairly long walk, nearly a mile I’d guess. We lived on the east side of town on Lover’s Lane, now Cache Avenue. Cache AVENUE? Jeez!

There were one-room schools at Elk and Moose and Kelly, further north in lands of controversy: Teton National Park and the Rockefeller holdings. (“Park extension” battle, let’s talk about that some other time). Kids in those schools were terrific spellers. They were the ones living the authentic life of pioneer isolation, especially in winter. They hungered for Jackson, bright lights at the town square, especially on Saturdays. “Pa, let’’s go to town.” I heard that more than once.

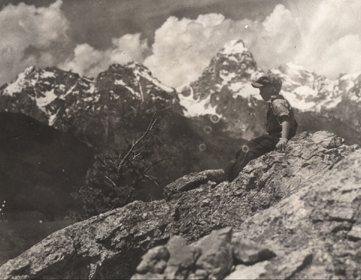

Our valley did possess something many western towns didn’t, very tight enclosure by big mountain ranges. Night came early. I want to talk about kids growing up in the shadows of those mountains. In our young minds the Jackson’s Hole country was not wilderness. We didn’’t know the word. It was our home range, that’s all, extending into the unknown beyond the high horizons. It was there for us to find. Year by year we went higher, entranced by new horizons that guarded more rough country. On our second attempt on Jackson Peak we made it to the top and stood triumphant at the USGS cairn.

One day we found two bear traps built of logs, each about six feet long by two and a half wide by two or three high with a vertical wooden door that could be raised above the entrance and connected to a trigger in back, baited, we surmised, with a carcass or big smelly slab of meat. These signs of human presence didn’t offend us. On the contrary, they were gratifying tokens of early history. We imagined that those old bear traps were maybe, just maybe, made by a mountain man of the fur trade heyday. And when we met a modern fur trapper on Sheep creek we couldn’t help trying hard to picture him as a mountain man. He, however, regaled us with some personal squabble he and a land owner had engaged in. That was of no interest, not nearly romantic enough.

We were kids on a roll, ranging into our world in pairs or trios and sometimes four or five. We dug up buffalo bones in the swamplands of Flat Creek; found arrowheads once in a great while; explored the cliffs of “Almer’s Butte,” on the Elk Refuge. (Almer Nelson was the refuge manager); toppled big rocks from high cliffs; crawled into tiny caves; watched animals; found nests of hawks and owls. Each year’s summer days found us better able to keep a steady pace into the eight and nine thousand foot levels. We didn’t bother with the Tetons until much later. Too far away.

Then something happened. We had a scare. It happened on an overnight from the head of Cache creek into the Granite creek drainage. All went well at first, but somehow we strayed too high, missed the easy pass. The mountains turned strange and night came on as we tried one more time to locate ourselves on the Forest Service map that showed lines of streams, locations of mountain tops, trails and roads, but no contours. Giving that up, we found a somewhat level place, built a fire, ate something and huddled around the coals and flames, the night black and chilly. We fed the fire for a while, then let it go out, tried to sleep, without blankets.

I won’t speak for the other kids, but it was my first time to feel afraid in mountains. Being lost in unknown country can be really scary, especially if it comes at you suddenly, totally unexpected. And it lasts, it nibbles at you. Meeting a bear at close quarters is scary too, but it’s soon over; one of you blinks and you go your separate ways, although Forney Cole, caretaker of Countess Gazika’s summertime retreat ranch at the head of Flat Creek, would rise from the grave to tell, at great length, about the time he was attacked by a black bear. He played dead while the bear mauled him. When the bear, for unknown reasons, turned to go, Forney reared up, grabbed a heavy beaver-gnawed stick, hit the bear one mighty blow, ending the struggle. Bleeding and hurting, Forney got into his Model T pickup, headed for town. A modern Hugh Glass.

We roused up from sleep to meet a beautiful blue sky morning, travelled on, still puzzled, but hopeful. We contoured steep slopes, picked up a few stones we decided were agates. We saw some cliffs above masses of Douglas fir and aspen, cliffs of Granite creek color and style. Familiarity flooded in, fear vanished.

But not entirely, because I remember. I’ve marked that little trek as the beginning of a long dawning, discovering, clue by clue, that wild country is neither friend nor foe. Nor does “the wild” always come equipped with big, bad beasts that can eat you. The wild is of us and everywhere; it is most definitely not a thing that you boldly venture in and take. Not a Holy Grail. My guess is that nature is a very complicated situation, beautiful at times, and always, ultimately mysterious, and that we are inside it and there’s no escape. Thoreau spent a lifetime trying to sort this out.

By the time we kids shifted across our little town to the high school the lure of mountains was as strong as ever, but we had learned a few things: how to imagine terrain from thin, fussy lines on poor maps; when climbing to falcon or hawk nests it’s best to test footholds and handholds before trusting them; don’t build camp fires on forest duff (Charles and I learned that the hard way by starting our own little forest fire); take it slow and easy (I’d put that one at the top of the list); at cliff tops beware of wind. And so on, elementary, learned by guess and by god. We came out alive, another strange thing.

We grew up with those mountains as a most natural part of our youthful rangings. I doubt if we suspected the mountains would haunt us for all the years ahead. We were naive and romantic, instructed by books such as “Two Little Savages” by Ernest Thompson Seton and Zane Grey novels, and by movies, Hoot Gibson and those other Hollywood guys under big hats galloping endlessly around and around, passing the same tall rock again and again. But mountains had already taken hold, long before we found those books, saw those movies. And now I can at least partway understand how kids in places like Chicago and Harlem, Brooklyn and New Orleans and Boston can never shake those places. And when the wreckers and gentrificationers move in, it’s a huge tearing and ripping inside life.

When did we learn that we lived in the center of a huge wilderness? I don’’t know. Adult talk I suppose. And there began the separation, the abstraction. In The Abstract Wild, Jack Turner writes, “All knowledge has a shadow … At the core of the present conjunction of preservation and biological science–the heritage of Leopold–lies a contradiction. We face a choice, a choice that is fundamentally moral. To ignore it is mere cowardice. Shall we remake nature according to biological theory? [or ]Shall we accept the wild?’’ (Brackets mine).

When I walk the wooden sidewalks of my home town, noticing the crowds and the astoundingly glitzy dumbed-down offerings, I am usually in a hurry, like everybody else. Gone are the leisurely meetings of people at the end of the day at the post office. Gone the dances in people’s living rooms, the home-made music, the ease of hard lives. Sometimes, though, a few moments at a cup of coffee or even waiting for a dive through traffic, a feeling of loss gets to me. What brings us here?

Should I repeat the standard answer? Okay. We and everything else … air, water, plots of earth … have become commodities, traded, trimmed, wrapped in hypocritic plastic and sold down the river. But I would add another twist: so many good people live in Jackson, the town and the valley, in the midst of all that insult. Weird times. If by chance you catch the Jackson Blues, here’s a suggestion. Drive on north and pull off at one of those scenic turn-offs, get out of your car, lock it. Look at the Tetons if you feel like it, but after a while turn, look east. There’s Blacktail Butte. Never mind the name, it’s a lateral moraine built by one of the glaciers that once upon a time ruled this place. Never mind those names either, just walk across the sage flats till you come to an ancient artifact, a dry irrigation canal. Cross that. Walk into one of the big gullies, smell the aspens. Don’t feel obliged to get to the top. There’s nothing up there that any of us needs. Oh, a more lofty view I suppose, but who needs that, really and truly? We’re trying to get basic here, okay?

You’re feeling the ground under your feet, you’re lifting one leg at a time over deadfalls, you might hear a mule deer bouncing away, you might see one. You’ll see all sorts of things there. In spite of the continual distant roar of the highway, in spite of the horse trail on the other side of the butte used by dudes once in a while, this is public land and wild enough and you have a right to be there. I’m hoping you will feel downright happy. I’m hoping you will notice a lightness…

That’s the shedding of commodity wrappings.

MARTIN MURIE died on January 28, 2012 but his words will always live on, here in The Zephyr.

Click here to read Jim Stiles’ tribute to Martin Murie in June/July’s Take it or Leave it.

To read the PDF version of this article, click here.

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!