Not long ago, a barn that had stood in my Colorado hometown for 90 years was demolished, but not before a land developer tried to purchase it for his new ranch.

An old red barn.

A wealthy real estate magnate.

But first: The Ute Indians.

***

Gaze at a map of Colorado. Even if it’s a run of the mill road atlas, there will be plenty to see. Wide swaths of National Forest and a few National Parks and Monuments show up in various shades of green, a sign of topography and scenery. Blue lines of rivers flow from the center of the state like spokes of a wheel, and their names are well known: Platte, Rio Grande, Arkansas, Colorado. The eastern half appears to be dull, but the straight roads and lack of forest signifies the spartan beauty of the high plains, a fertile part of the state where the buffalo once roamed. The names of historic locales dot the map—Cripple Creek, Leadville, Central City—along with the names of historical personages like Carson, Pike and Cortez.

You might also notice a handful of indigenous names such as the Uncompahgre River, the Sawatch Mountains, the town of Tabernash, and Kiowa County among many others, but one thing that’s easy to overlook is designated tribal land, i.e, Indian reservations. This is due to the fact that the gold rush of the 1860’s sparked an era of racist violence that drove entire tribes out of the state for good. In 1859, Colorado was home to more than a half dozen tribes, including the Ute, Cheyenne, Comanche, Arapaho, Kiowa, Pawnee, and the occasional Lakota, with many others wandering in to trade or hunt. Just 10 years later, none but the Ute remained, and in 1881, most of them were forcibly marched to a pair of desolate reservations in Utah. The remaining Ute were corralled upon a narrow strip of land along the New Mexico border, and that reservation represents the single scrap of the state that Colorado’s white politicians agreed—reluctantly—to leave in Ute hands.

As you might expect, the tale of the Ute removal from Colorado is replete with broken promises, politicians pandering to angry mobs, murders and massacres on all sides, and, as was always the case, white folks demanding land, treaties be damned. Beneath those sordid but all too common details lay the true theme of this and every other story of Indian to white relations: a clash of cultures that viewed the earth and its resources through completely different eyes.

To Colorado’s settlers, the roving Ute had no concept of the value of their own land, and therefore no connection to it. Sure, an 1868 treaty had given the mountains and valleys of western Colorado to the Ute for their “absolute and undisturbed use and occupation”, but that was foolish—the work of eastern do-gooders who couldn’t grasp the fact that the Indians were wasteful. Why should a few thousand Ute be entitled to their own vast hunting preserve (a third of the state!) when tens of thousands of white farmers and miners (and merchants, and clerks, and speculators) were ready to turn the wilderness into something useful? In their view, only the whites really understood the land’s worth, for only they knew how to capitalize on the wealth hidden in the rich soil, in the rich veins of ore. According to the newspapers and elected leaders of the day, the Ute way of life was childlike, especially when compared to the machine-like efficiency of industrialized civilization, and if Indians were going to continue living such a debased lifestyle then they were going to have to do it somewhere else.

The belief that Indians had no meaningful connection to the land had been used to excuse the state sponsored removal of Indians for over half a century, and the same sentiment was strong in Colorado during the 1870’s. Because the Ute were nomadic, because they hadn’t yet evolved out of “savagery” or “barbarism” and become wheat farmers, then they could be moved—guilt free—to suit the needs of the expanding American nation. The Indians, any Indians, would hardly notice the difference, as their simpleton culture could play out its waning days on any piece of property, preferably one that whites didn’t want.

Now we know better, or at least we should. Turns out that hundreds of years spent upon a home ground results in a connection to place that modern Americans can only guess at, and native tribes such as the Ute were intimately tied to their chunk of earth. The details of this connection are many and varied, but include, at a minimum, an encyclopedic understanding of the plants and how to utilize them; awareness of shifting weather and climate patterns and how to adjust to them; deep knowledge of animals large and small, their movements, and how to hunt or trap them as needed and, perhaps most importantly, an evolving tribal lore passed down over generations in songs and stories.

That last one, the songs and stories, tied the people to their land in a manner that transcended mere practical survival skills. Lacking science, or at least lacking the kind of textbook zoology or chemistry we think of as scientific, the indigenous folks found order in the natural phenomena that surrounded them via myths that delved into the backstory of landmarks, plants and especially the animals. A deep canyon or a mountain lake was the birthplace of the original human beings. The lone mountain sheltered spirits that brewed up life giving rainstorms. The cottontail rabbit had brown spots because it was scorched when the once fiery moon rolled over our planet. There’s even a story that explains why dogs sniff each others’ asses. No peak was too high, no rodent too small to be the subject of a colorful yarn.

These legends were supplemented by the memories of the people themselves through a rich oral tradition that recorded events, human and otherwise, that had unfolded over the centuries. Remembering the hammer of drought. Remembering the plenty of rainy years. Remembering the fallen warriors. Remembering the coming of the horses and the arrival of the sickness. Remembering those who came before. The dust of their ancestors really did float on the breeze, and that dust pulsed with stories, both mythical and real, that bound the people to the soil beneath their feet. No wonder that many natives became sick and died when they were forced to move onto distant reservations. They died of homesickness.

White Colorado settlers of the 1860’s and 70’s understood none of this. How could they? They were immigrants who had left the stories and memories of own homelands behind in search of greener pastures. Many of them were escaping the horrific aftermath of the recent Civil War. They were looking to start anew, and to them the land was a blank slate. Almost none of them had been born in Colorado, many not even in the United States, and the deeper rhythms of the Rocky Mountains, the kind of wisdom that can only be learned by generations of patient listening, eluded them completely. To the settlers and speculators, the region had no history, and very little to offer beyond deeded ownership or pay dirt to ease their gold fever. The whites were rootless, or at least uprooted, and in their arrogance they projected the same upon the Ute, and forced most of them from the state.

***

Fast forward 130 years. The Southern Rocky Mountains are dotted with “Ute Trail” motels, “Ute” cafes, “Ute” hotels, “Ute” inns, “Ute” trading posts, and “Ute” bars, but the Ute themselves are a vague notion in most parts of Colorado, and modern civilization has spread to every corner of the state. Remote deserts are strip mined and fracked for the energy required to run summer air conditioners and winter chairlifts. Rivers are dammed and diverted to keep alfalfa farms and suburban lawns green. Fertile valleys are plowed, planted, and fenced off and/or covered in housing subdivisions. Even the most rugged and formerly inaccessible peaks are busy with hikers eager to write their names on the mountaintop registry. Wolves gone. Grizzlies gone. Wolverines gone. Buffalo gone. From east to west, north to south, the entirety of the Ute homeland has been transformed.

Near the middle of the boxy state, just north of center, a small town rests in a mountain valley. The Ute once hunted elk and gathered berries here in the summer and fall en route to buffalo hunts on the eastern plains or winter camps in the western canyons. There were no valuable minerals in this valley, but there was good pasture, and the Ute were quickly crowded out by ranchers and cattle, followed in turn by railroaders, loggers, construction workers, real estate agents, and various forms of outdoor enthusiasts.

Despite the changes, descendants of the early waves of settlers have endured the cold valley and its booms and busts for a century or so, and they’ve put down roots. They don’t have the connection to the place that the Ute had—no one will ever have that connection again—but they know a thing or two about the valley, and have cobbled together a few generations worth of memories that tie them to it. Big snowstorms and spring floods. Bone chilling cold snaps. Forest fires. Visits from Presidents. Ten of thousands of glorious mountain sunsets. The coming of the pavement, the ski runs, the golf course. A walk across town, or a drive in the woods, conjures up more personal memories: Great granddad’s potato patch on the hill; grandma’s favorite raspberry patch, dad’s trophy elk, a first kiss beneath the train trestle. A visit to the cemetery brings bittersweet sorrow, and the forgotten, or fading, voices of family come and gone. The dust of these ancestors may not be carried on the wind, but their bodies are buried beneath the cemetery pines at the edge of town.

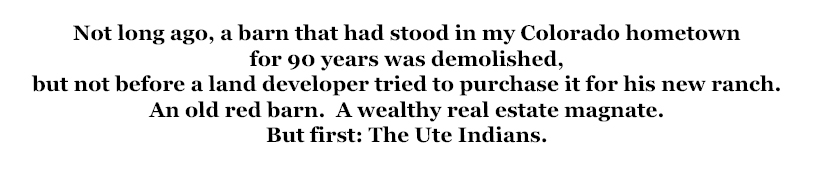

And then there’s the red barn. The family patriarch built it soon after he arrived from Sweden so his draft horses could find shelter from the cold and snow, a purpose it served for more than half a century. Over the years, six generations of family lived their lives within sight of this barn, and each used it to meet the evolving needs of the era. A garage for the model T Ford. Blacksmith shop. Art studio. Practice space for the teenage punk band. Storage for the stuff that accumulates when lifetimes play out in one piece of ground. The family added to the barn’s physical structure—a hayloft, a coat of paint, a foundation—and they added to its treasury of stories as small dramas unfolded within its dusty walls. Dances and poker games. Hay forts and rolls in the hay. First cigarettes and nips of whiskey. Fist fights and ghost sightings. All of it, every moment, forever intertwined with the familiar incense of dust, horse manure, and old wood.

By 2008, the barn was the only one left in town, and one of just a handful still standing anywhere on that side of the county. Then the economy went into a tailspin, and the family that owned it was faced with a dilemma. Seems that town planners, working long after the barn had been built at what was once the edge of town, had included the property in a commercial zone. This created high taxes on a structure that wasn’t producing a single dollar just as reliable work was becoming scarce. Debts piled up. Official historic designation and related grant money was ruled out by the practical additions made over the years, specifically a modest garage attached to the side of the barn, so they decided—with great sadness—to tear it down and sell the property.

In the midst of all this, a wealthy land developer arrived in town. Despite the fact that the valley was just beginning to catch its breath following a decade-long blitzkrieg of rapid growth, he looked around and immediately pronounced the place “underdeveloped.” Backed by Texas money, lean and mean from cranking out projects in Aspen and California, he looked at the sweeping hay meadows at the edge of town and envisioned something bigger and bolder—something that could transform the sleepy town into a world class mountain resort. Hotels! Shopping! Movie theaters! “Green” buildings! “Affordable” housing! “Walkable” neighborhoods. Bike paths! In their ignorance, the simpleminded locals may have overlooked the gold mine beneath their very feet, but he understood what the land was worth, and he would see that it paid.

He bought a ranch just outside of town, pushed the elderly caretaker out, and got to work on a master plan bound to change the destiny of the valley. He enlisted a small army of lawyers and began throwing his weight around, demanding stoplights, variances, services, and even annexation from the cash strapped town government. When the town balked, he threatened lawsuits. When local businesses refused to sell to him—not their products, but their actual business—he opened up identical shops next door and siphoned long time family incomes into his own bottomless pockets. He was ruthless and calculating—intensely focused on manifesting his vision of what the town should be, and anyone who questioned his motives or his narrow view of reality was asking for trouble.

Somehow, the developer got wind of the red barn’s demise, and decided it would look good on his new ranch. He sent his people to tell the family that he wanted it, and offered a large sum of money. The family—working class waitresses, ski patrollers, paramedics, and construction workers—surely could have used the extra cash, but they spurned his repeated offers. The developer was angry and confused. The barn would soon be a useless pile of splintered lumber, and he was puzzled when the family wouldn’t sell, especially when he was being so generous—after all, it was just an old barn.

But to the family, it wasn’t just an old barn. It was a storehouse of memories, a symbol of who they were and where they came from, and a direct link to their forebears, one of whom had built it by the sweat of his brow. The barn wasn’t an ornament, it was a story, and it was forever tied to a very specific and special place. Like the mountains themselves, the barn had always been there, day in and day out, and it simply did not belong on a stranger’s trophy ranch. Had they sold the barn, and allowed it to be moved, they would have saved the structure but killed its spirit—and killed a part of their own collective spirit as well.

The rootless, restless developer will never be able to understand this. Blinded by dreams of future riches, he refuses to acknowledge that others have been there longer than he, and that the wisdom they’ve gained over the years has meaning or even practical use. To him, the barn—indeed, the entire valley—is a blank slate awaiting a story that he alone will author, and the local yokel families will have no say in how it unfolds. Like the arrogant, land hungry settlers of yore, who viewed an entire race of people as ignorant savages who impeded progress, the real estate developer feels that he knows best, and everyone should either embrace his master planned community or get the hell out of the way.

***

The Gold Rush ended long ago, but gold fever still plagues Colorful Colorado.

To read the PDF version of this page, click here.

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!

Loved this piece Charlie! You are truly a talented and gifted writer. Linda Wommack

Great piece. Loved how the modern story resonates with historical one.

Great story!