EDITOR’S NOTE: The Zephyr was only in its fourth year of publication when the effects of an already runaway recreation/tourist/amenities industry became a real worry, at least to me. The reality of it was a sobering wake-up call and I tried to express those concerns in this April 1991 essay. Reading it 22 years later reminds me how futile resistance to Moab’s chaotic transformation turned out to be. But I take some comfort. at least, in knowing that we tried…JS

Everything seems to change.

Where are the pals I used to ride with?

…Gone to a land so strange.”

Old West and New West

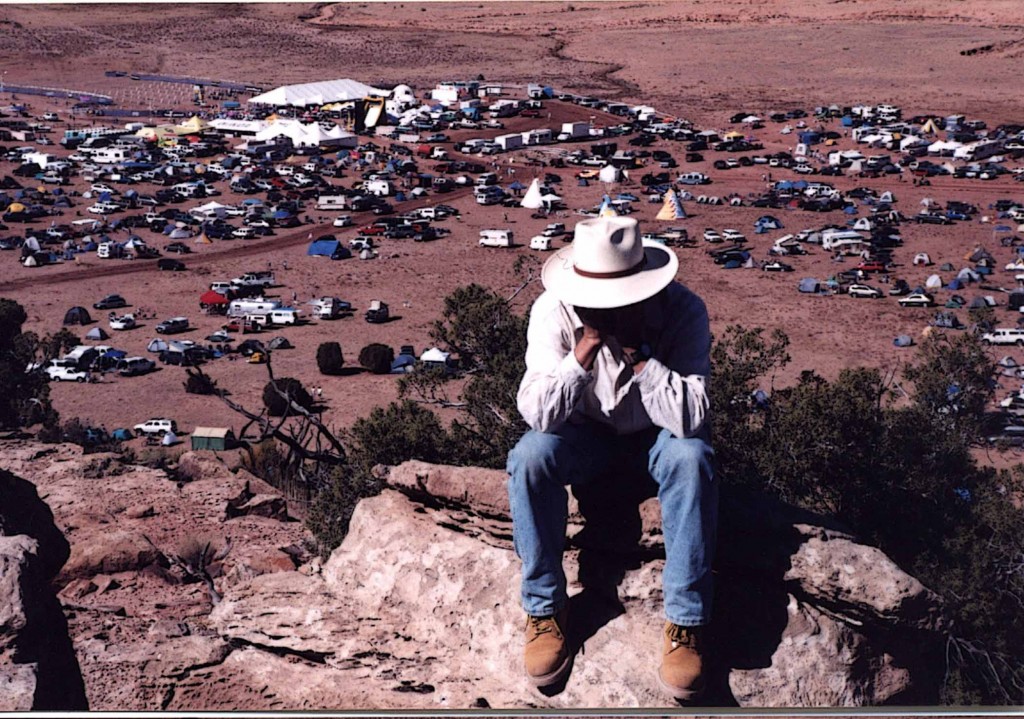

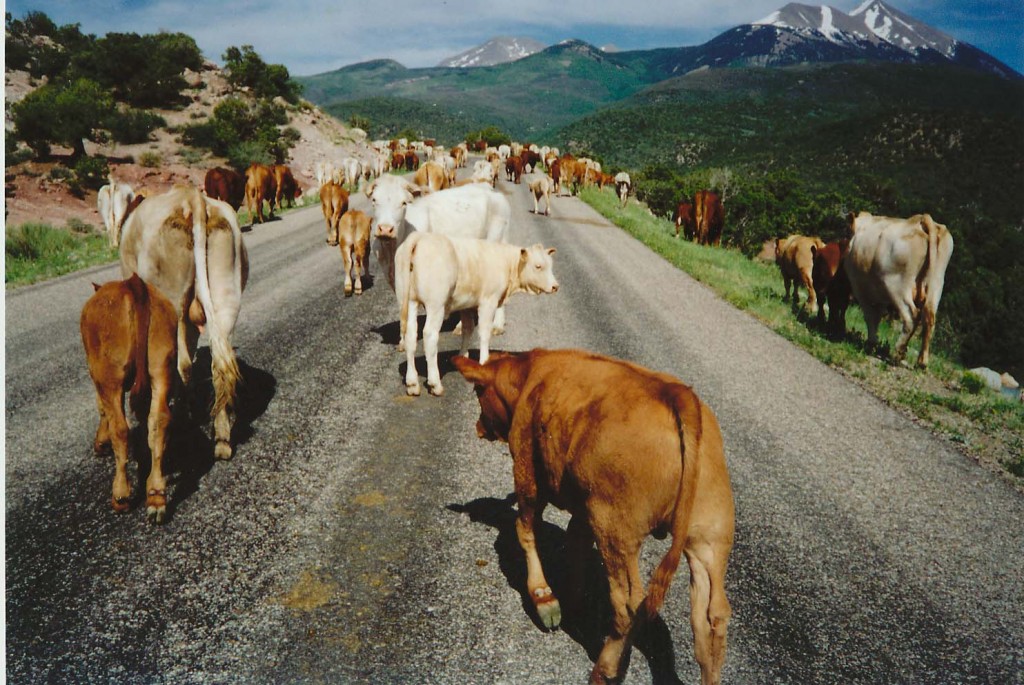

In my never-ending quest to try to make some sense out of what is happening to us here in the rural West, I haven’t “been to the mountain top,” but I’ve been to the Sand Flats above town, and the view from there is discouraging. A few days ago, my attorney and I took a drive to survey the destruction. (I hadn’t been back since the “Easter Weekend Riots”) Besides being surprised at the number of campers still enduring the 100 degree heat, I was shocked at my reaction to another sight that should have only caused more aggravation. After wading through a hundred or more bikers, we came around a corner and saw local rancher Don Holyoak with a couple dozen cows. Smelly, stupid, fly-ridden cows…”stinking bovines,” Abbey used to call them.

I was glad to see them.

Don’t get me wrong. I still believe that the mismanaged use of our public lands for cattle has done immeasurable damage to the land, has fouled countless streams and water sources, and been a burden on the U.S. taxpayer. In fact, efforts by the extractive industries to literally tear up the West for maximum profit continues at an alarming and devastating rate. But I have become painfully aware of a shift in my thinking that has left me confused and bewildered. There are more than a few of us longtime environmentalists who are suffering from some kind of an identity crisis. Edward Abbey once wrote, “The idea of wilderness needs no defense; it only needs more defenders.” But to be a defender of the West has changed in 15 years. Just who poses the greatest threat to the West? Where does the real danger lie? I’m afraid it’s become more complicated than I ever thought it could.

This is not just another complaint about our changing town– the New Moab. What’s happening here is happening elsewhere. And what’s coming may be bigger than even we doomsayers would dare predict. Barring a miracle, we are about to enter a new phase, the last phase, in the taming of the West. When it’s over it won’t be “the West” anymore. We all know “how the West was won.” What we are about to see is “how the West was done.” To use a recently popular expression, pretty soon, you can stick a fork in it. And all of us, no matter how much we love the country bear responsibility.

When I first moved here in the late 70s, the threats to the canyon country were obvious and easy to define. The extractive industries…oil and gas, uranium, timber and cattle…those operations that actually reduced the quality of the resource, were the natural target of environmentalists. In those years, the desert was turned upside down by seismic crews and oil rigs, chaining operations, and a never-ending series of harebrained ideas to exploit the fragile Western landscape. For almost a year, we could see the big mercury vapor lights on an Exxon oil rig in Gold Basin, a place too beautiful for such a monstrous intrusion. Seismic crews worked right to the edge of Arches and Canyonlands National Parks, collecting geologic information that they could sell to other energy companies. In their wake, they left hundreds of miles of ugly scars that would take centuries to heal. The Department of Energy wanted to build a high-level nuclear repository adjacent to the Needles in San Juan County. The BLM continued to chain thousands of acres of pinion-juniper forest as part of its “range improvement” policy (and one of my favorite euphemisms, I might add, next to “nuclear exchange”).

In short, there was plenty to complain about. And we complained loudly, well, and often. We, who actually lived here in the heart of the country we were trying to defend, felt honored and proud to be a part of the battle on the front lines. It was, after all, not easy to live in the rural west; it truly required a sacrifice. Just trying to find a way to eke out a living was a challenge, for most jobs were low paying and many were seasonal. In addition, a poor infrastructure, a lack of cultural opportunities, under funded schools, and an extremely closed conservative population made it difficult for an “outsider” to survive. That is why, despite warnings by some about the threat of “industrial tourism” for more than 25 years, the effect on the West by all those millions of gawkers seemed trivial when compared to the damage a bulldozer could do.

There were, of course, blatant exceptions. Some of the West’s national parks began to show the effect of abuse and overuse decades ago. Several small towns, from Aspen and Telluride, to Jackson and Taos, were transformed from sleepy, even dying, little mining and ranching villages, to bustling communities full of trendy restaurants and boutiques. They became rustic playgrounds for the rich and famous.

But they were the exception to the rule. The rest of the West changed very little from a demographic standpoint. Generation after generation grew up in the same small western communities. The towns looked the same, decade after decade. A person could go away for years and come back to his home town and find the same grocer behind the cash register, the same postmaster behind the stamp window. But it was more than just the way these little towns looked. It was the pace of life itself that set such communities apart. While some may call it stagnation, it was comforting to find such continuity in a world that turns itself inside out on a daily basis.

All that is changing at breakneck speed. We are watching, in effect, the last land rush, and when it’s over, the West will bear little resemblance to what it still is today. The decay of America’s cities and urban areas, the congestion, the pollution, the crime…the stress of urban life, is driving millions to the wide open spaces. And the explosive growth of tourism is creating, for the first time, the climate necessary for that kind of exodus. For the first time, West Coast immigrants can dream of moving to a rural community and making more than a subsistence living. No sacrifice is needed to sell a $500,000 home in California, buy a $100,000 home in a small Western town, invest $200,000 in a business, and put the rest in the bank. A few hope to be modern day Charlie Steens, dreaming of get-rich-quick schemes. But this time, fortunes won’t be made with a second hand drill rig and a thousand dollar grubstake. Speculators buy up land for JB’s and McDonald’s franchises the way miners staked uranium claims in the 50s.

As long as people in the cities can sell their homes at a great profit (and so far, the prices continue to rise exorbitantly), and can take that money and reinvest here, where the prices are still substantially lower, we will continue to see this remarkable inflow of humanity.

Is it all that bad? In some ways, it’s not. Critics of tourism as an economic base claim that such an industry is too unstable, that a town that builds its economy around tourism is asking for trouble, that sooner or later, the bubble will burst and all the tourists will go somewhere else. But I just don’t see that happening. While energy towns have gone boom and bust for decades, I cannot think of a single tourist town that ever went belly up. Maybe business in these communities has ebbed and flowed with the national or regional economy, but dry up and blow away? Never.

So…with an established tourist base, a changing community profile that demands better educational and cultural opportunities, and a larger tax base, positive changes to the community are inevitable. And yet, in a perverse way, those same improvements represent the final nails in the West’s coffin, changes that guarantee the demise of the West as we know it.

For me, “the West” is a lot more than the sum of its parts. The West is, first of all, the resource itself. The West is the desert, the canyons, the mountains and the wildlife that roams among them. It’s the wildflowers that bloom in the most unexpected places and the gnarled spruce that clings to life at 12,000 feet. It’s the polished skies and the exploding cotton clouds that loom over the high peaks each afternoon. It’s the kangaroo rats and fence lizards that we see all the time and the cougar that we wait a lifetime to see just once for a fleeting moment.

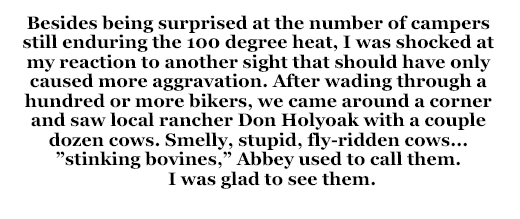

But the West is more than that.

The intangible aspect of the West is as vital to its survival as the resource itself. It’s the solitude, the silence, an almost pleasant loneliness that this country evokes in the souls of those that love it. These are an integral part of the West as a state of mind. Abbey could not describe this land without references to the “strange and mysterious” country that he loved so much…”the voodoo rocks.” Even the inhospitable aspect of the West itself became a quality to be admired and respected. You loved the West on its terms and made the sacrifices that were required to be a part of it. Solitude was not something to avoid, it was something to love and respect, and even to depend on.

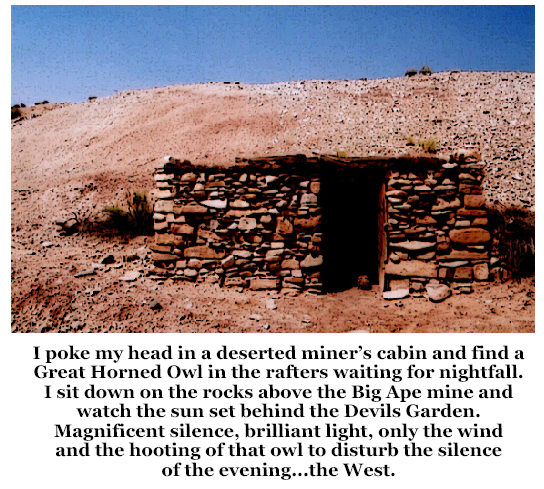

So today, as I re-examine what the West is, I find a strange contradiction in the experiences I seek out. For instance, I can hike into the badlands country north of Arches, into country that was torn apart 40 years ago by the uranium industry and which still bears the scars, and there amidst the rubble can feel like I’m in the West. I poke my head in a deserted miner’s cabin and find a Great Horned Owl in the rafters waiting for nightfall. I sit down on the rocks above the Big Ape mine and watch the sun set behind the Devils Garden. Magnificent silence, brilliant light, only the wind and the hooting of that owl to disturb the silence of the evening…the West.

But I can hike to Delicate Arch, where the resource has been preserved for sure, but also promoted to the far corners of the planet, and I feel like I’m in Disneyland. Surrounded by dozens of camera snapping, video taping tourists, screaming kids, and well- armed rangers, I think to myself…this is not the West.

But it may be the future of the West. It seems to be what the People want. Those wonderful intangibles have lost their appeal to many of the New Westerners. In fact, all that solitude appears to scare a lot of them to death. Look at the way recent visitors, and even our most recent residents, “explore” the country. They travel in groups. Some might say they travel in herds…that we are seeing one herd (livestock) being driven from the country, only to be replaced by another. Where visitors once came here for the peace and solitude and beauty of the land, now they come for “breathtaking thrills.” Those who found a trip to the canyon country to be akin to a religious experience have been replaced to a large degree by “recreationists” who regard this country as a playground, and who seem to have a diminished or non-existent environmental ethic. So people come here looking for organized ways of having fun.

Before skiing became popular, the mountains were cold and hostile and forbidding…they were nice to look at from a safe distance. But the sport changed everything. Here in the desert, it was the same story. Hot, desolate…a nice place to watch from the comfort of an air conditioned car, but who the hell would want to live in this godforsaken place. When I was a ranger, tourists thought I’d been assigned to Arches as some kind of punishment…”What did you do wrong to get stuck in this hell hole, boy?”

Again, the sport, in this case mountain biking, changed everything. It changed the very reason people come here. We went from mystical to macho, from watching a hawk, to “riding the ‘rawk'” (biking lingo). From “desert mystics” to “adrenalin junkies.”

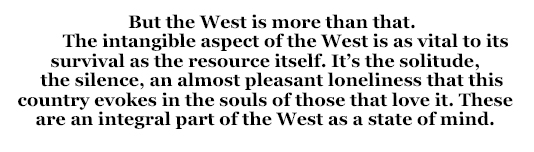

The sport, of course, and the reputation and notoriety it creates, spawns the ever growing stream of businesses that are created to provide equipment and services for those organized thrills. And once a newer more hip tourist infrastructure is in place, with a plethora of restaurants, boutiques, Southwest art galleries, and jewelry shops, the nouveau riche suddenly find the area much more appealing, and start looking for little “ranchettes” upon which to build their million dollar summer homes.

And here is the most frustrating aspect of the change. While some speculators see the West as a product to be marketed and sold like soap or headache remedies, a great majority of the new businesses that cater to the tourists and recreationists are simply people who are longing to escape their miserable, polluted, crime-ridden urban existences for the simpler life. The overwhelming number of new residents in Moab didn’t come here to get rich. They simply want to live here.

Once they arrive, they wring their hands and hope that the situation doesn’t get any worse. I’ve done my own share of hand wringing. This paper’s circulation has doubled in one year and I should be thrilled, but it’s also an indication of what’s happening to the town…we’re booming. Does my paper somehow encourage more people to move here? The fact is, sheer numbers of immigrants alone, will almost certainly mean that what they’re running from…congestion, pollution, crime and stress, will most certainly follow them here. That, in turn, will diminish the quality of everyone’s life. But who has the right to say “Go away?”

And so, it continues. Californians, Coloradans from the Front Range, as well as entrepreneurs from across the country, are buying up commercial and private property in rural counties all over the West. In Wayne County, out-of-state property sales are at an all time high and property values have increased dramatically. There is a housing shortage in Emery County because so many homes are owned by absentee landlords. In New Mexico and Arizona, the story is the same.

Is there a solution to all this? Is there a way to preserve the West? Can we protect the resource and those precious intangibles? Actually, I think the answer is “no.” Fighting strip mines and oil wells was easy. They were such black and white targets. What’s happening now is so much more insidious. Where would someone even begin?

The truth is, all the ordinances and regulations in the world can’t change our lifestyle. We can’t begin to see that the Real Enemy is the face we see in the mirror every day of our lives. Humans and their toys…What a deadly combination.

Someone once asked the great humorist Dorothy Parker to use the word “horticulture” in a sentence. She replied, “You can lead a horticulture, but you can’t make her think.”

Ms. Parker would have understood the New West.

Jim Stiles is Founder and Co-Publisher of the Canyon Country Zephyr.

To read the PDF version of this article, click here.

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!

always topical. so many people axually think like this, and upon reading the article, AGREE. more and more i’m thinkin’: if you truly love a place, you’ll leave little impact. if impact is obvious, you’ll stay away altogether. i haven’t regularly visited Moab since about 1995!

like the desert rat M John Fayhee, when wandering out in the open spaces, i prefer off-piste; off the trail; to where few if any go.

earlier this year my wife and i wanted to mountain-bike out in the desert west of our town (Whitewater, CO) and … went to Green River, Utah! we were the most ‘mongo’, most fit, most glamourous mountain-bikers in town. and the scenery out and way from town wasn’t so bad. we could see snow on the glimmering Manti-LaSals not so much beckoning, as warning us away.