The world of light and space that Edward Abbey found at Arches National Monument in the late 1950s and early 1960s and that he wrote about in Desert Solitaire survives in Great Basin National Park in far eastern Nevada.

The following numbers may be revealing in this regard. Arches National Park and Great Basin National Park are virtually the same size (76,769 acres and 77,180 acres respectively), but in 2012 the former had 1,070,577 visitors while the latter had 94,850. A ratio of over 11:1. The last time Arches had fewer than 100,000 annual visitors was 1964, when it was still a national monument. (Google “Park Statistics – Arches National Park” and “http://www.national parked.com/US/Great_Basin/

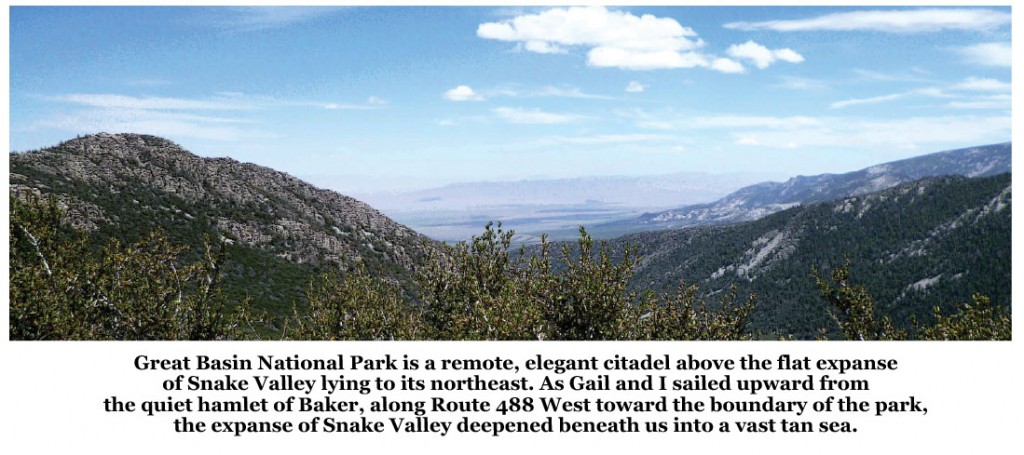

Great Basin National Park is a remote, elegant citadel above the flat expanse of Snake Valley lying to its northeast. As Gail and I sailed upward from the quiet hamlet of Baker, along Route 488 West toward the boundary of the park, the expanse of Snake Valley deepened beneath us into a vast tan sea. From an eastward-looking overlook in the pinyon-juniper woodlands we gazed out 70 miles or more, past the Nevada state line, past Snake Valley itself, well into Utah. Out there somewhere are the ruins of Topaz, an internment camp where our government imprisoned Japanese Americans during World War II.

Everything at the park happens against the backdrop of Snake Valley and the eastward reaching desert far beneath. I can still close my eyes and see that vivid tan horizon, as well as the distant rooster tails of dust from out-of-the-way trucks shooting across the dirt roads. All of the immense Snake Valley and the empty, low-lying desert out to the horizon, which lends this park its grandeur, is outside the park boundary.

Wheeler Peak, 13,063 feet, the park’s capstone, is a sentinel in all directions. In the six miles between the eastern boundary of the park – at 6,500 feet – and the peak itself the land slopes abruptly upward through slender ecosystems: pinion-juniper woodlands; mixed conifers, including Douglas-fir, ponderosa pine and aspen; subalpine forest, including Englemann spruce and ancient bristlecone pine; and alpine tundra, including cryptogamic crusts of lichens, mosses, cyanobacteria, and fungi, and a thinning glacier.

The park has two visitor centers: the newer one at the edge of the village of Baker and the other just outside Lehman Caves, the other major attraction. Unless Gail and I happened to catch the park rangers on an exceptionally good day, their relaxed faces and easy gaits revealed their relief at being assigned here. I suspect that’s because here they can be rangers according to the old ideals: answering pleasant, nuanced questions about nature’s workings from curious, well informed visitors.

Because here the rangers don’t have to break up drunken fistfights or nag litterers or silence throbbing car and truck radios or explain grade school scientific data or carry firearms. Or at least not very often. To feel solitude in this place the rangers merely have to stroll away from the visitor center they’re assigned to, take a few deep breaths, and gaze out at Snake Valley.

Edward Abbey knew that once the roads in Arches were paved, the vicious cycle of motorized traffic and industrial tourism would obliterate the elegant silence there, thereby destroying what was vital. And that his fellow Americans, ever seeking a bit more comfort and convenience, would unwittingly aid and abet in that obliteration. Abbey’s book was an elegy, and what he said has come to pass in national parks across the country.

The secret to Great Basin National Park’s continuing isolation is that it’s still a pain in the ass to get there. Specifically, it’s a little too far for most tourists to drive and, if they do, they have to pass through a desert that seems a little too empty and forbidding-looking, and if they actually do arrive, well, the population of Baker is under a hundred and lacks typical tourist amenities, meaning that the streets are empty and they won’t find a top-grade mocha latte in town.

Which is what Gail and I like about Baker.

The nearest town offering the range of services expected by tourists is Ely, population 4200+, 73 miles to the west. Which has a full cadre of eccentric motels (in the best sense), plenty of restaurants (even a Starbucks mini-bar in the old hotel), as well as gambling 24/7 and a lawfully operated cathouse. And a grocery store. And crisp local humor.

This state of affairs may be why the number of visitors to the park has wobbled back and forth since 1993, when it had its second highest year of visitation. It is true that in 2012 the park recorded its most visitors ever, and in both 2011 and 2012 visitation exceeded 90,000 for the first time. But this doesn’t yet make for an upward trend.

Yes, (typed with a sigh), at some point the chain motels, restaurants, and adrenalin-spiked recreational outfits may yet descend upon Baker, infecting it with the commercial buzz we know so well in Moab, Estes Park, and elsewhere. And if they do, no one who lives in the vicinity will be in a position to oppose the massive influx of money and jobs. And Wheeler Peak Scenic Drive will be clogged with cars, trucks and God knows what else.

But thus far the unique obscurity of this desert has been keeping Great Basin National Park safe.

The irony is that this very obscurity almost destroyed the desert before the park was created.

This is why: in 1979 the MX missile project was proposed by the U.S. Air Force, which unfortunately garnered the support of President Jimmy Carter. If it had been carried out, the project would have devastated a swath of Great Basin Desert 100 miles long and over 50 miles wide. This is virtually all the desert valley that Great Basin National Park now overlooks, not only to the north and east but to the south as well, including all of Snake Valley.

In essence, the MX was a colossal scheme of hide and seek. Roughly 200 intercontinental ballistic missiles were to be situated there, each with 23 underground shelters along an underground track. All of the missiles were to be moved from one shelter to another in order to confuse Soviet spy satellites. Dummy missiles were to be involved in order to further confuse said spy satellites. The tracks and shelters for the missiles were to be spread throughout this gigantic rectangle of desert land.

The planned construction time was seven years.

During the time the MX missile project was being debated and fought over, Wheeler Peak and environs were located in national forest land, while Lehman Caves itself was a national monument only one square mile in size. Had the MX plan been approved it would have comprised one of the largest military bases in the world if not the largest. Given the secrecy of the project, official paranoia about security would have been in overdrive. No civilians or even ordinary military personnel would have been allowed anywhere near the razor-wire fences or past the armed guards at the gates, and certainly not on the high ground near Wheeler Peak where they could have espied events on the base with telescopes. Under these circumstances Great Basin National Park would never have been created and likely Lehman Caves would have been shut down.

And even if under such circumstances the park could somehow have been created, few people would have been willing to drive through hundreds of miles of forlorn desert in order to stand on Wheeler Peak Scenic Drive overlooking such a ghoulish scene.

The opposition to the MX came from various quarters, obviously including the local residents and environmental groups. And interestingly the Mormon Church, which on May 5, 1981, to the surprise of many, issued a document flatly opposing the project. Entitled the “First Presidency Statement,” it included the following paragraph: “Our fathers came to this western area to establish a base from which to carry the gospel of peace to the peoples of the earth. It is ironic, and a denial of the very essence of that gospel, that in this same general area there should be constructed a mammoth weapons system potentially capable of destroying much of civilization.”

Note this paragraph because we’re coming back to it.

While a variety of factors tipped the scales against the MX, there is little doubt that the opposition of the Mormon Church was crucial. Consider the following from a news story, “Anti-MX Missile Stand Surprised Some Mormons, Too,” in the May 2, 2011, edition of The Salt Lake Tribune: “While President Ronald Reagan had not yet tipped his hand, Utah’s entire congressional delegation wanted the MX in Utah and Nevada. Nearly every elected state leader embraced the MX out of patriotic duty or the desire for economic development or both.

…

“According to polls at the time, support among Utahns for the MX deployment in the Great Basin had dropped from 80 percent to less than 50 percent by the spring of 1981. After the First Presidency’s Statement, 75 percent of Utahns opposed the MX missile coming to the state’s backyard.

“Mormons in Congress quickly reversed their support for bringing the MX to Utah and Nevada.

…

“The First Presidency’s Statement ‘meant a hell of a lot,’ says Ed Firmage Sr., then a University of Utah law professor who was active in the anti-MX camp. ‘It killed it.’”

Now I’m not an advocate for Mormonism. Once out of curiosity I tried reading the Book of Mormon but couldn’t gain any traction in it. And while Mormon culture surely has its attractive features, as far as I can tell it is highly conservative in orientation with significant right wing leanings. Not friendly epistemological territory for the likes of me.

But when it comes to protecting desert lands, especially in the Great Basin, the quoted paragraph from the First Presidency Statement is noteworthy. It declares “this western area,” namely the Utah deserts, to be a sacred land dedicated for the propagation of peace. For that land to be dedicated instead to the propagation of massive death was too much for these Mormon leaders to swallow. In their integrity they could not condone such a desecration.

Good for them.

So that’s our next irony: that it took a conservative-to-right-wing religious organization to save the desert valleys that made Great Basin National Park possible.

I know of no other Judeo-Christian religion or denomination with any meaningful power that is willing to treat any stretch of wild land in North America as sacred. You have to turn to indigenous cultures to find this kind of wisdom, which is why I pay so much attention to them.

That said let’s explore the meaning of “sacred land,” which I believe is paradoxical. In a number of stories I’ve said that the wildness of the land or in this case desert land is sacred. This expression is my effort to redress our civilization’s lack of respect and concern for undomesticated ecosystems and landscapes it isn’t using for self-serving purposes. But even though calling wild land sacred may be useful, doing so creates an artificial separation between the land itself and us. Because strictly speaking there is no such separation. We ARE that desert sunset that we see and when we gaze at it, our own eyes are gazing back at us. I believe that the paradox of knowing not simply that the land is sacred but that we ARE the land itself is much of indigenous spirituality.

Now for the final ironies in our story. Sadly it was Jimmy Carter, one of my very favorite Presidents because of his humility and near-prophetic insight, who supported the colossally destructive MX missile plan. And it was President Ronald Reagan who in 1981 finally axed that program. A weird irony for me because when I was a young man in the 1980s it was also Ronald Reagan who, with his inviting smile and cheery talk, tragically seduced the American public into embracing market fundamentalism and into brushing aside crucial environmental concerns. I witnessed all of that, including the lasting aftereffects. Even today our most powerful institutions as well as a critical mass of the public remain committed to Reagan’s essential legacy.

With climate change coming right at us, well…that’s bad.

And now for the crowning irony: it was also Ronald Reagan who in 1986 signed the bill creating Great Basin National Park. Of course the Gipper had to leave his right wing thumbprint on the park by insisting (1) that the park boundaries exclude private mining claims and other private land and (2) that grazing continue unabated within the park boundaries. But he did sign the bill.

The takeaway hypothesis from all this is that sometimes people who do REALLY good things are those we have the least countenance with.

Note – I have gratefully utilized Gretchen M. Baker’s Great Basin National Park: A Guide to the Park and Surrounding Area, published in 2012 by the Utah State University Press, as a key source in writing this story.

Furthermore: to all you citizens of Baker, Nevada, I stand ready to apologize in writing if I have inaccurately claimed that a top-grade cup of mocha latte is not available to the public at a reasonable price in your town.

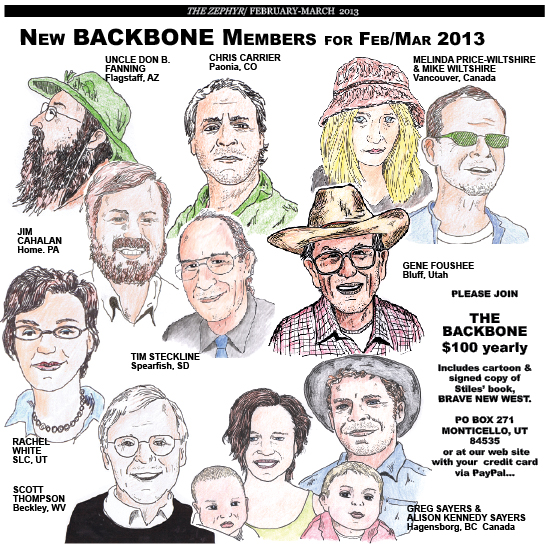

SCOTT THOMPSON is a regular contributor to the Zephyr.

He lives in Beckley, WV.

To read the PDF version of this article, click here and here.

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!

The most political I have ever been was my opposition to the Vietnam War. I was a young man and involved and clever enough to figure out a personal dodge.

Then when the MX Missile System was proposed, my bluster returned. I had learned to love the isolation of what I called the west desert. The absurdity was so apparent to me and lost on others who did not know the beauty of the isolation. I too held it against Jimmy Carter. When the LDS church finally did oppose it, Gov. Matheson, a proponent, changed his tune, and the thing slowly went into oblivion. I went to the hearings that were sponsored by, I believe, the Air Force. They were just what you can imagine them to be: A public display that appeared to be concerned for the community. I have backpacked the majestic Mount Wheeler and even spent New Year’s at 10,000 feet one cold night. I enjoyed the article and it brought back memories.