EDITOR’S NOTE: I’ve printed or posted this story two or three times over the past 25 years, but here it is again. I like the way these kinds of memories make me feel. Thanks…JS

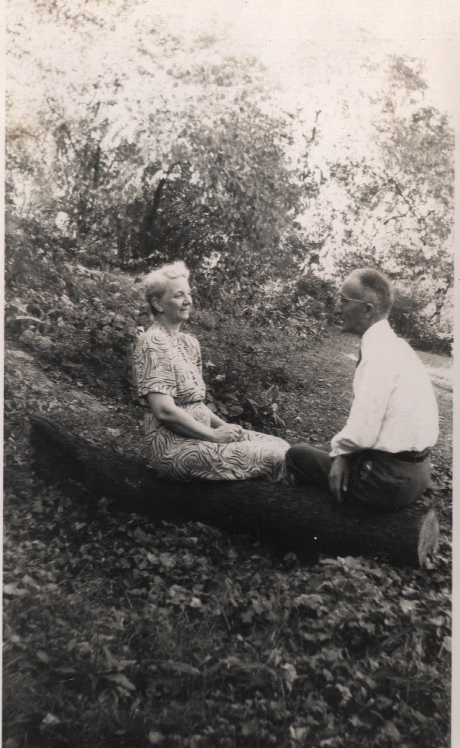

This time of year, I always think of my grandparents. They died many years ago; in fact, more time has passed since their passing than the years I was able to spend with them. Yet, there is scarcely a day that passes that I do not think of Grandpa and Grandma. My grandfather was born in Concordia, Kansas in 1882, the oldest of six children and, as a boy, once saw Wyatt Earp; yet he lived to see men walk on the moon. He used to tell me he’d lived the best part of America and I think he was probably right.

Frank Montfort was not a great success; at least in the way most of us measure it these days. He never made a lot of money and he never acquired any fame. In fact, he struggled to make a living throughout much of the Depression and at one point, very briefly, when he’d hit rock bottom, could only find comfort in a bottle of whiskey. But he overcame all that, driven by his own pride and his love for his family.

My grandparents stay close to my heart after all these years. They were fair-minded without being judgmental, honest without being opinionated…and their love was unconditional. As a teenager I was in and out of trouble from time to time, but my grandparents’ support never wavered. My grandpa would smile and put his arm on my shoulder and say, “Jim, I don’t always understand you, but I love you and I’m behind you 100%.” It’s amazing how much those few words can mean.

Recently, on a trip home, I found some journals that my grandfather had kept for almost 20 years, buried in the bottom of his cedar chest. We had not known they existed. The family read his entries cover to cover, and what struck us all was the absence, in all those years, of any unkind sentiment toward anyone–not even my crazy Aunt Elizabeth with the blue hair. He was incapable of it.

At Christmas I remember this story about my grandparents and my mother during a particularly rough winter more than 70 years ago. Most of what follows is true…

My mother was only five years old in the cold and bitter winter of 1932. It was bitter for more reasons than the freezing temperatures and early snowfalls that fell upon the Ohio River Valley. For twenty-five million Americans, one-third of the work force. There were no jobs and no prospect for work. Families that just a few years earlier had been a part of the nation’s safe and secure middle class, now found themselves homeless and hungry. My mother’s father, my grandfather, was one of the unemployed.

My mother was only five years old in the cold and bitter winter of 1932. It was bitter for more reasons than the freezing temperatures and early snowfalls that fell upon the Ohio River Valley. For twenty-five million Americans, one-third of the work force. There were no jobs and no prospect for work. Families that just a few years earlier had been a part of the nation’s safe and secure middle class, now found themselves homeless and hungry. My mother’s father, my grandfather, was one of the unemployed.

A few weeks earlier, Franklin Roosevelt had been elected President and he had promised a New Deal for

Americans. In a few weeks he would tell his fellow citizens that “the only thing they had to fear was Fear itself.” For now, however, there was the basic fear of hunger and cold and hopelessness.

Americans. In a few weeks he would tell his fellow citizens that “the only thing they had to fear was Fear itself.” For now, however, there was the basic fear of hunger and cold and hopelessness.

Sue (my mother’s name) often overheard the grim conversations between her parents and it scared her. How was he going to keep food on the table, my grandfather would ask my grandmother, and she would softly reassure him, “You’ll find a way, Frank.” Sue asked her father why they were poor; he smiled wanly and tried to explain, “It’s the Depression,” he said. “Everybody’s poor.”

That helped a little. At least her family wasn’t alone. But the Depression? It was hard to explain to a five year old.

As the month of December and the Christmas season approached, Frank and Susan and Sue Montfort could be thankful that they still had their home, that they’d canned many vegetables from their summer garden for the winter, and that they were all healthy. But job prospects were grim and the family’s savings were almost depleted. While window shopping on Fourth Street, Sue had eyed a red checkered dress at Stewart’s Dry Goods. But her mother dampened her hopes—Santa was having a bad year too, she explained. There may not be many presents under the tree. My grandfather feared there might not even be a tree. Or a turkey. Nothing. It was that tight.

One afternoon, Frank decided to take a walk. Somehow he felt better when he was moving, for when he sat, he thought. He thought about his family’s dilemma and his inability to change it. So, wrapped in a worn wool overcoat, he shoved his hands deep in the coat’s pockets and moved briskly up Birchwood to Frankfort Ave.

Frankfort Avenue was the commercial center of the Crescent Hills section of Louisville. Its sidewalks were lined with small shops and markets, although many of them were closed and boarded up. As he watched the lined and worried faces of the people he passed, my grandfather stifled the urge to sink into self-pity. He knew he had no right to feel victimized for he was surrounded by other victims. He was not alone.

For that reason, Frank almost felt guilty when he was suddenly confronted with a stroke of remarkable good luck. He had just passed beneath the marquee of the old Crescent Theatre when a man appeared behind the ticket window of the box office. The man was holding a small cardboard sign. In crude handwritten letters it said: HELP WANTED.

For a long moment my grandfather could scarcely believe his eyes or good fortune before he ran inside. In a few minutes, Frank Montfort was the new ticket collector at the Crescent Theatre. He glanced through the ticket window and saw a dozen faces fall as the manager removed the “help wanted” sign. He knew that a matter of seconds could have changed everything, and he could have been on the outside looking in. But he wisely decided not to flog himself too severely for his good fortune. After all, he’d been recently plagued by nothing but bad news—he could go home today with a smile on his face.

In reality, Frank was happier than he had a right to be. The job was nothing permanent; he was hired only for a week to help out during the Christmas rush. And the job paid twenty dollars. Twenty bucks. But that amount of cash could go a long way in 1932. He could get a turkey and all the side-dishes that go with it to make a proper Christmas dinner. He could afford a tree, and maybe if he was very careful, still have enough money left over to get that red checkered dress.

My grandfather brought the news home to his wife and daughter, and the next day he started work at the theatre. Collecting tickets at a movie matinee did not exactly challenge Frank’s intellect, but it never even occurred to him to complain. He was grateful just to be there and the days passed quickly. On the morning of Christmas Eve, the manager called him into the office, and handed him a crisp $20 bill.

Whether the theatre would need additional help after Christmas depended on the crowds the manager explained, and he added—stay in touch. My grandfather nodded, shook the man’s hand, and put the bill in his coat pocket.

There was an extra bounce in his step as Frank walked briskly down Frankfort Ave. His sister Louise and her husband Ham planned to stop by the house later. Ham and Louise had a car, and with their help, Frank and Susan hoped to find a turkey, a tree and that special Christmas dress for Sue.

As he prepared to cross the street to Birchwood Avenue, Frank passed a man standing alone by a lamppost. His face was dirty and unshaven, his clothes were in tatters. His hands were wrapped in rags. Clutched in his fingers was a pint of Kentucky bourbon, a cheap brand, and as my grandfather walked in front of him, the man tried to hide the bottle. My grandfather looked away; Frank knew that had the breaks gone differently, the man could just as easily have been himself. Again.

As he prepared to cross the street to Birchwood Avenue, Frank passed a man standing alone by a lamppost. His face was dirty and unshaven, his clothes were in tatters. His hands were wrapped in rags. Clutched in his fingers was a pint of Kentucky bourbon, a cheap brand, and as my grandfather walked in front of him, the man tried to hide the bottle. My grandfather looked away; Frank knew that had the breaks gone differently, the man could just as easily have been himself. Again.

Mother and daughter were waiting when Frank appeared around the corner. He was almost running when he hit the front steps. Susan lifted the hat from his head and brushed off the snow that was just beginning to fall. Frank smiled and reached into his coat pocket…

“I’d better turn this over to you before ….”

He stopped short. The broad smile vanished. He reached deeper into his pocket but the bill was not there.

“Check your other pocket,” my grandmother suggested, and he did. But he knew where he’d placed the $20 bill. He went back to the pocket and probed every inch of it. And he felt along the seam where the threads had worn out and separated and created a ragged hole just large enough for a piece of paper money to silently slip through and fall to the ground.

“It’s gone,” my grandfather said. “It’s gone.” His lips formed the words again, but he made no sound. He sank down in the couch and buried his face in his hands. For a moment, no one said anything. No one moved. But my grandmother, an eternal optimist, broke the silence.

“Maybe you can find it,” she said. “Maybe it’s still lying on the sidewalk.”

Frank looked scornfully at his wife and shook his head. She had to be kidding, he thought. That money probably never had a chance to reach the sidewalk before someone else grabbed it. Not in these times. But Susan insisted that he at least try, and for lack of a better idea, Frank agreed.

My grandfather scoured the sidewalk and gutter as he dashed up Birchwood. He walked in a sort of crouch, his eyes glued to the ground, and he must have looked very strange to the pedestrians he passed. When he reached Frankfort Avenue, he knew it was hopeless. Before, the sidewalks were relatively empty, but here the foot traffic was heavy. There were people everywhere. But for form’s sake, if nothing else, he continued onward toward the theatre.

He moved slowly along the sidewalk’s edge, hoping the bill had fallen over the curb where it might not be noticed. He was still in that crouch staring intently at the concrete, when a voice spoke to him from over his shoulder. Frank spun around.

“Lookin’ for something?”

It was the man with the cheap bourbon…..

He was still leaning against the lamp post. My grandfather shifted his weight uneasily and tried to explain, but he was embarrassed and disheartened and tired and he could not speak.

“Forget it,” said the man with the bottle. He took a swig, winced and wiped his mouth with his sleeve.

“Anyway,” he went on, “I figured you’d be back.”

He lifted one worn out leather shoe with a flapping sole from the sidewalk. There was something beneath it.

“Merry Christmas,” said the man.

It was the twenty-dollar bill.

Darkness had chased away the last light of day, my grandmother peered through the frosted windowpanes into the blackness, but it was her daughter who first saw the two figures, dimly lit by the streetlights, trudging through the snow and slush. Out of the silence of a snowfall, came the sounds. It was the sound of two grown men singing Jingle Bells, at the very top of their lungs.

On Christmas Day, the Montforts had a guest for dinner.

JIM STILES is the Founder and Co-Publisher of the Canyon Country Zephyr.

To read the PDF version of this article, click here.

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!

Hi there Jim! I love your site and your paper. I’m a Canadian journalist/novelist and I’m working on a new novel about the Great Depression in rural Canada and Toronto and I just happened across this story. Thank you. It’s wonderful and a real testament to your grandparents. Thank you so much. Cathi

Jim, I loved the story about your grandparents. I was born during a time when the great depression still had a grip on the way people thought and worked.

What a beautiful story. How have I not read it before now? Anyway, thank you. Also, I love the photo of your grandparents on the log. Have a lovely Christmas.

Thank you for sharing the beautiful story.

Thank you Jim such a good story, your grandparents were amazing people I am sure.