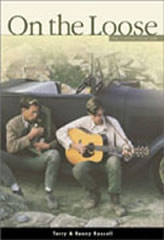

EDITOR’S NOTE: If Renny Russell had a nickel for every time someone told him how “On the Loose” changed his life, I suspect Renny would still be living quietly and unobtrusively, off the grid, somewhere in the remote mountains of New Mexico. And wondering what to do with all those damn nickels. The lessons he learned from the wilderness–the refuge that he and his brother loved so dearly, never abandoned him. Even if those lessons hurt like hell.

To try and explain the effect Renny and Terry and ‘On the Loose’ had on so many of us is impossible. You had to be there. Now Renny tells the rest of a story that played such a significant role in defining the hearts and souls of a generation…a generation that sometimes feels as lost now as it did then.

We are honored to present this excerpt, the introduction to Renny Russell’s “Rock Me on the Water.” I hope you will take the time to pursue and read this book for yourself. It completes the Circle.

JS

My brother’s body was found circling in an eddy above Florence Creek Rapid. The discovery came after an exhaustive search of the Green River in Utah. Terry had just turned twenty-one and did not leave this world easily. The good die young, they say, but the young die hard. Even in death, Terry was stubborn.

My brother’s body was found circling in an eddy above Florence Creek Rapid. The discovery came after an exhaustive search of the Green River in Utah. Terry had just turned twenty-one and did not leave this world easily. The good die young, they say, but the young die hard. Even in death, Terry was stubborn.

The boat that retrieved his body arrived at the eight-foot-high diversion dam at Tusher Rapid with a six-inch gash cut in her bottom. Another rescue boat wrecked a motor. The following day, the hearse carrying my brother from Green River, Utah, to the crematorium in Ogden had engine failure and had to be towed. There seemed to be a kind of cosmic resistance to his untimely departure.

This last thought mingles with the steam from my cup of tea as it rises and dissipates in the air. I glance out the window and notice more new houses under construction on the valley floor below my home in the Sangre de Cristo Mountains of New Mexico. Has it really been four decades since the world lost Terry?

On June 11, 1965, my brother and I launched our small rubber boat in the flood-swollen waters of the  Green River. Five days later, a rapid surprised us and our raft flipped. I was washed up on a beach in Desolation Canyon, one of the most isolated regions in the West. I made my way downriver to an abandoned ranch, where I scrounged for food and clothes among dust, snakes, rats, and cobwebs. With a flea-bitten blanket and a pair of ancient leather boots, enveloped in a cloud of despair, I began a seventy-mile walk to the town of Green River.

Green River. Five days later, a rapid surprised us and our raft flipped. I was washed up on a beach in Desolation Canyon, one of the most isolated regions in the West. I made my way downriver to an abandoned ranch, where I scrounged for food and clothes among dust, snakes, rats, and cobwebs. With a flea-bitten blanket and a pair of ancient leather boots, enveloped in a cloud of despair, I began a seventy-mile walk to the town of Green River.

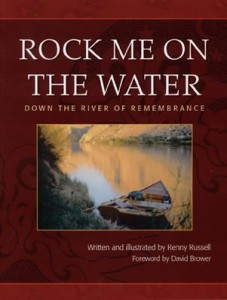

I finish my tea as the early sun strikes the high ridges of Ute Mountain, an extinct volcano that rises from the high-desert plateau. It looks like the back of a giant whale. I’m awake early because I have a mission. Next to me on the table is a worn leather-bound manuscript. On its spine, in gold lettering, is embossed “On The Loose.” It is the original bound manuscript of calligraphy and photographs that Terry and I created in the mid-’60s. This solitary volume of two brothers’ wilderness rambles spawned a million copies when the Sierra Club published it. It became an anthem for our generation. I had not been ready to revisit the book since Terry died, keeping it wrapped in blue velvet.

On this morning, I carefully put it in my backpack and begin walking up the mountain behind my house. I  pass through the dense piñon and juniper forest and then, higher on the mountain, into aspen groves dotted with clumps of subalpine fir. Finally, I break through into open tundra, where ravens play on the thermals. On the bare-boned summit, massive cumulus clouds gather, smelling of rain. There are ominous rumblings of distant thunder.

pass through the dense piñon and juniper forest and then, higher on the mountain, into aspen groves dotted with clumps of subalpine fir. Finally, I break through into open tundra, where ravens play on the thermals. On the bare-boned summit, massive cumulus clouds gather, smelling of rain. There are ominous rumblings of distant thunder.

I remove the book from its velvet covering as if it were the Gutenberg Bible and reverently open the leather cover. I touch the title page and am transported to a different time and place. I spend the afternoon with our book, slowly turning its pages, reveling in all the good humor and love that went into its making. Through the clouds, sun spills across the pages, their photographs still firmly attached, and reveals the faint pencil markings that guided Terry’s hand as he lettered the text. In memory I walk the trails Terry and I traveled. Was it all a dream? With each turn of the page, my brother’s spirit leaps into the high alpine air and is set free. I knew it was time to write a new book and finish a story that demanded closure.

So consumed am I by the thought that I fail to remember that a ridge is no place to be in a thunderstorm. Hurriedly, I wrap On the Loose in its velvet cover and return it to my pack. I move quickly down the mountain, among lightning bolts, seeking shelter in the timber.

Back home, I go to the oldest part of my house. To terminate the mindless wandering I had done in search of solace after Terry died, I bought land in northern New Mexico. I was seduced by the light and landscape—the pure, clear, golden light of mountains named after the blood of Christ. The landscape took hold of me—its mesas and high rolling hills, its sensuous round-topped peaks. I found my home in country that is neither desert nor mountain, but a composite—where cactus grows among the aspen; where ground cover is dense with oak, piñon, and juniper; where the undergrowth conceals the wanderings of fox, raccoon, elk, coyote, mountain lion, and bear. I found a home where sweet spring water rises from the heart of the mountain, where tall pines guard entrances to canyons, where jagged granite spires loom, where the savanna stretches northwest for a hundred miles to the high peaks of Colorado’s San Juan Mountains, where distant blue-gray volcanoes rise up and merge with the horizon.

Back home, I go to the oldest part of my house. To terminate the mindless wandering I had done in search of solace after Terry died, I bought land in northern New Mexico. I was seduced by the light and landscape—the pure, clear, golden light of mountains named after the blood of Christ. The landscape took hold of me—its mesas and high rolling hills, its sensuous round-topped peaks. I found my home in country that is neither desert nor mountain, but a composite—where cactus grows among the aspen; where ground cover is dense with oak, piñon, and juniper; where the undergrowth conceals the wanderings of fox, raccoon, elk, coyote, mountain lion, and bear. I found a home where sweet spring water rises from the heart of the mountain, where tall pines guard entrances to canyons, where jagged granite spires loom, where the savanna stretches northwest for a hundred miles to the high peaks of Colorado’s San Juan Mountains, where distant blue-gray volcanoes rise up and merge with the horizon.

Here I built an octagonal room that over the years metamorphosed into the heart and soul of my home. Each subsequent room branched out from the original, like limbs of my body. Some rooms I’ve torn down, others I’ve rebuilt. In the center of the octagon, a large ponderosa log supports the roof. Beams radiate from it, connecting the corners and forming a chambered nautilus. Each chamber has borne witness to a life of triumphs and follies, forged in large part by the immense legacy and love of living On the Loose.

On one wall hangs an eclectic collection of photographs and calligraphy, watchful and diligent testimonials to a brotherly bond forged by our mutual love and passion for wilderness. I move a stack of my own paintings to get a closer look.

On one wall hangs an eclectic collection of photographs and calligraphy, watchful and diligent testimonials to a brotherly bond forged by our mutual love and passion for wilderness. I move a stack of my own paintings to get a closer look.

In a delicately carved gold frame are the words of Henry David Thoreau, immortalized in calligraphy by Terry as a gift for my high school commencement in 1964: “Remember thy Creator in the days of thy youth. Rise free from care before the dawn, and seek adventures. Let the noon find thee by other lakes, and the night overtake thee everywhere at home. There are no larger fields than these, no worthier games than may be here played . . .”

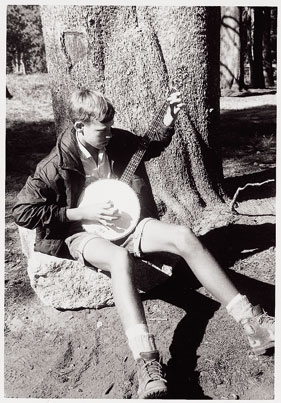

Next to it, an intricate pen-and-ink drawing, reminiscent of the work of the finest Old World engravers, reads “Happy Birthday. With Love Forever. To Ma. From Terry.” Another calligraphy piece celebrates words of Arthur Rimbaud: “The goal in life is the transformation of the self into a maker of poetry or beauty. This is more important than anything done along the way.” The words are centered in a swirling pattern in gold-leaf design. Below that is a snapshot of Terry playing his autoharp, a touchstone image that found its way into our book. Terry scribed these words to accompany it: “It’s a shame that a race so broadly conceived should end with most lives so narrowly confined.”

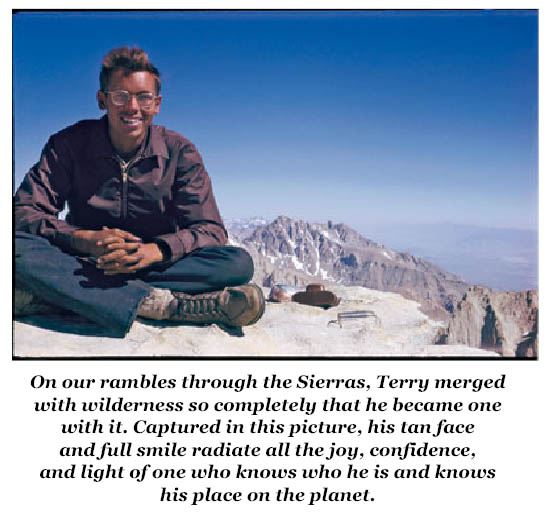

My eyes linger last and longest on a picture of my brother that I took on top of Mount Whitney in the Sierra Nevada in 1963 at the culmination of our grueling walk on the John Muir Trail. Silhouetted against a cobalt-blue sky, Terry seems larger than life. He fills most of the frame, so large that he dwarfs the distant horizon and the dim shadow of the Salton Sea far to the southeast. On our rambles through the Sierras, Terry merged with wilderness so completely that he became one with it. Captured in this picture, his tan face and full smile radiate all the joy, confidence, and light of one who knows who he is and knows his place on the planet. I give Terry a wink and feel an urgency to return to the Green River, to retrace our fateful journey and begin a book that tells our story.

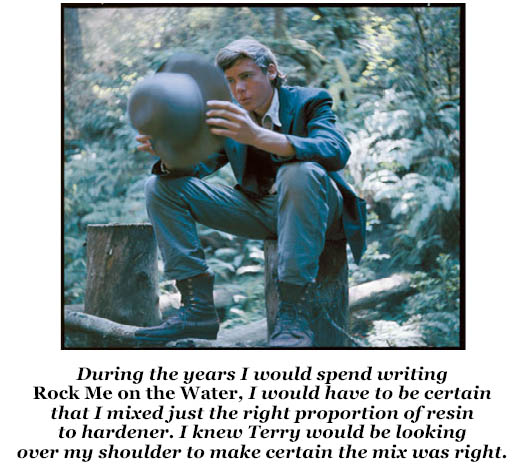

My plan to return to the river has been brewing for some time, and the dream to build my own boat in which to run it is nearly realized. In my shop I put the finishing touches on the dory that will take me down the Green River and complete the circle Terry and I began on that June day in 1965. Gluing a last section of the gunwale, I concentrate on getting the proportions of resin and hardener just right. Too little hardener and the epoxy will never set up. Too much hardener and it may possibly catch fire or turn rock-hard before I can use it.

During the years I would spend writing Rock Me on the Water, I would have to be certain that I mixed just the right proportion of resin to hardener. I knew Terry would be looking over my shoulder to make certain the mix was right. He would let me know when the interface between past and present was a true bond, resilient and enduring. Late that afternoon, as the glue dries, I sit quietly in the light and admire the graceful lines and curves of my boat. An adventure down the Green River will take me back in time, just as it will propel me forward into the future. I begin to comprehend the enormity of my return.

At Steer Ridge Rapid, where Terry drowned and where I was, in a sense, reborn, I will complete the circle. There the river will reveal that the last note of a song is merely the beginning of another. At the end of my childhood, when the rapids released me to that river beach, I began another song. With the writing of this book, that song is complete.

Rock Me on the Water has revived in me the essence of On the Loose. Freedom was and still is close to the heart of it. Indeed, freedom is what On the Loose was all about, a freedom born of wild places. The book is also a philosophical journey, a new painting for which On the Loose has primed the canvas and explores some of its ideological naiveté and revels in its innocence. It’s a furtherance of seminal ideas for those of us who came of age when On the Loose first appeared.

Many of my generation who grew up with On the Loose have been out there beyond the last and returned from the myth-countries; we have risked our lives in perilous encounters; we have beheld a world beyond men, and know what’s worth talking about. It’s time to celebrate our journeys and share our stories; to offer hope and alternatives; to inspire a new generation who will have to make crucial choices, not just for wilderness preservation, but also for the survival of all mankind.

Rock Me on the Water is but a single grain of sand upon the shore. It is to the Green River that I pay homage. It flows between the lines of this book and has passed like a timeless melody through my soul—our blood and waters merging in ceaseless flow.

Sangre de Cristo Mountains

New Mexico

Also, don’t forget to check out Renny’s artwork, from this issue of the Zephyr.

To read the PDF version of this article, click here.

To comment on this article, scroll to the bottom of the page.

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!