I’ve never been a fan of extreme sports, especially when they use Nature as the venue. Even as a young man in my twenties, the idea of stunt climbing and extreme recreation didn’t appeal to me. I am of the school of John Muir and Aldo Leopold and Edward Abbey. For me, these lands are special… sacred…and much more than something to climb up or jump from. And, more than anything, I don’t like the rush of adrenalin that others hunger for. I prefer tranquility. All these years later, my attitude hasn’t changed; if anything my lack of enthusiasm for extreme sports has grown, well, more extreme, for more reasons than you might imagine.

Consequently, to some, my antiquated attitude betrays the soul of an ‘old timer.’ I’m a fossil because I don’t want to wear a neon green squirrel suit or leap from tall pinnacles and Interstate highway bridges. That’s okay. As the wise man once said, I can live with that.

Over the years, I’ve penned a few stories about extreme sports and some of today’s most visible exhibitionist/recreationists—those who seem to pursue not only the thrill of a dangerous and reckless ‘sport’ but the adulation and worship that comes with it. For instance, I could not resist commenting on Dean Potter, who illegally scaled Delicate Arch a few years ago and who has cultivated almost mythic status for his daredevil feats. His devotees were not pleased.In the Zephyr comments section, one young climber named ‘Seth’ wrote: “People like you are the ones that turn it into an issue. Dean Potter has raised more awareness about nature and done more for the protection of our wildlife areas than an army of you idiots bitching on the internet will ever do, for eternity…It’s this geriatric community of do-nothings that wants to sit by and look at rock that is getting butthurt (sic).” He continued: “ It’s so sad, watching you people grow old and bitter, wanting the government to regulate everyone’s lives to suit your tastes.”

Seth’s friend ‘Sarah’ agreed. She told me, “…you have no business writing about rock climbing or its ethos, or otherwise raining judgments on something that is so clearly far from your daily desk job.”

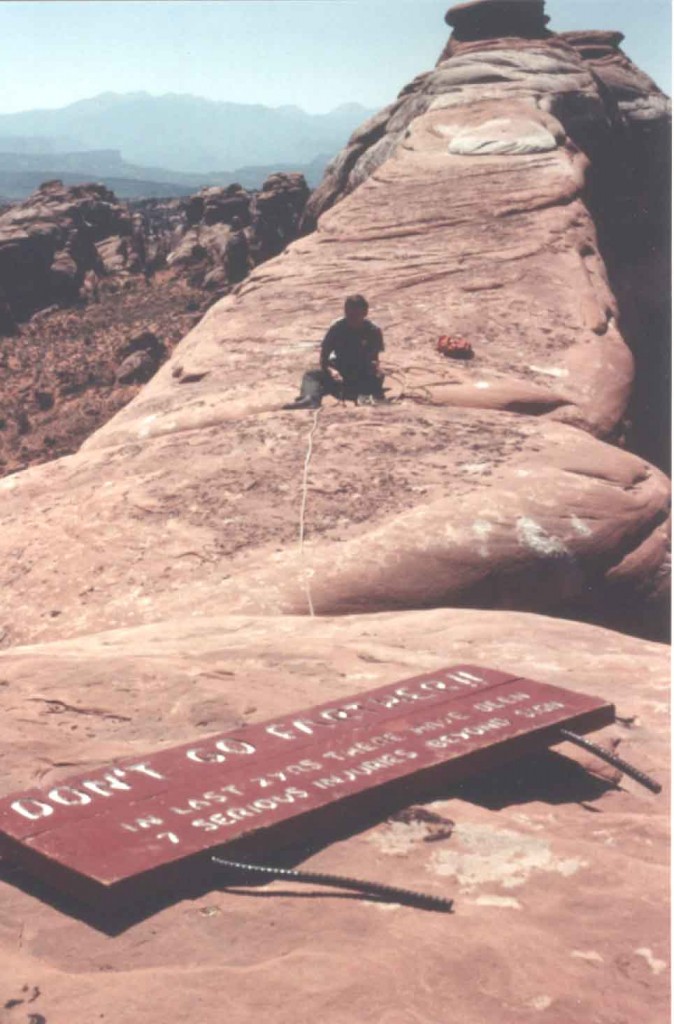

Well, that’s not exactly right. While I may spend more time now than I’d like to behind this cursed keyboard, when I was Seth and Sarah’s age, I was a search and rescue ranger at Arches National Park. For a decade, I sometimes risked life and limb, and often my patience, to rescue rock climbers from severe injury and death. I agree, it tainted my views on extreme sports.

We once found a young man rimrocked above Landscape Arch. He couldn’t move in any direction and was utterly terrified. Tourists heard his screams echoing down the canyon and contacted the rangers. We hauled our gear to the sandstone fin above him, and I descended to his location, hooked him into a harness and the other rangers pulled us back to the top. Its wasn’t even a vertical pitch , but he was frozen with fear.But the moment he was safe and out of his harness, he made a fist and pumped his arm and screamed, “MAN! What a f**king rush!”“Do you realize how close you just came to dying?” I asked.

We once found a young man rimrocked above Landscape Arch. He couldn’t move in any direction and was utterly terrified. Tourists heard his screams echoing down the canyon and contacted the rangers. We hauled our gear to the sandstone fin above him, and I descended to his location, hooked him into a harness and the other rangers pulled us back to the top. Its wasn’t even a vertical pitch , but he was frozen with fear.But the moment he was safe and out of his harness, he made a fist and pumped his arm and screamed, “MAN! What a f**king rush!”“Do you realize how close you just came to dying?” I asked.

“I can’t help it, man,” he exclaimed. “The rock is in my blood!”

My compadre Ranger Maki looked at him evenly and replied, “Keep this up and your blood will be on the rock.” He didn’t get it.

Over the years we rescued dozens of would-be under-qualified and over-confident thrill seekers. Some didn’t make it. One fell 125 feet to his death, trying to impress his girlfriend. His last words were, “Look how close to the edge I am.” Incredibly he was still conscious when we found him, but he was white with fear and in agony. He died on his way to the hospital of complete cardio-pulmonary collapse..

Another young man, scaling a rock wall near Park Avenue was supposed to be belayed by his friend below. But the friend forgot to take up the slack. He fell 50 feet and almost instantly, his abdomen began to swell. We got the call and rushed him to the hospital where Dr. Mayberry performed emergency surgery. Mayberry called in every nurse and staffer he could find and actually removed the boy’s intestines, all 23 feet. He strung them around the operating room and then inspected every inch of bowel. Finally he found a spot where the impact of the fall had telescoped and then collapsed the wall of the intestine upon itself. Nothing could pass through and so the young man was on the verge of literally exploding. Fortunately Doc Mayberry was there.

Still another died when he tried to free climb a wall near the Three Gossips. A miscalculation sent him over a 175 foot cliff. When his girlfriend found his body, he was unrecognizable. I’m sure the image haunted her dreams and her thoughts for years. It may still.

All this happened many years ago, and while the falls and mishaps were unsettling and sometimes tragic, they were relatively few and far between. Rock climbing was one of the rarest of activities. In my decade as a ranger, my time spent in searches and rescues was never as overwhelming as it must feel nowadays.

In 2014, there are new and terrifying ways to maim and kill oneself that we never dreamed of 25 years ago. From BASE jumps to Corona Arch swing-throughs to Squirrel Suit flyovers, to highlining between sandstone pinnacles, the opportunities for high-risk, adrenalin-fueled, seemingly suicidal acrobatics have exploded across the canyon country and beyond, to everywhere there’s an object or structure with enough altitude to jump from it. Of course, southeast Utah has a plethora of such places and so we can add these kinds of activities to its long “Capital” list. From “Uranium Capital” to “Mountain Bike Capital” to “BASE Jump Capital”…who knows what’s next?

Extreme sports has become an industry. Once the realm of the few, for only those with the resources and the nerve and, yes, the skill to perform these kinds of feats, now it’s a sub-culture for the many. The more affluent Gen-Xer’s and Millennials, with the financial resources to pursue what was once a cost-prohibitive sport, have arrived in Moab en masse, to pursue their daredevil impulses.The 2013 Grand County, Utah Search & Rescue statistics are mind-numbing. Clearly, people are coming to Moab in search of thrills, regardless of the risk.

Extreme sports has become an industry. Once the realm of the few, for only those with the resources and the nerve and, yes, the skill to perform these kinds of feats, now it’s a sub-culture for the many. The more affluent Gen-Xer’s and Millennials, with the financial resources to pursue what was once a cost-prohibitive sport, have arrived in Moab en masse, to pursue their daredevil impulses.The 2013 Grand County, Utah Search & Rescue statistics are mind-numbing. Clearly, people are coming to Moab in search of thrills, regardless of the risk.

But the number that no one can bear is the growing fatality list. By mid-2013, five young recreationists, all under 30, had died from climbing mishaps—from miscalculations and faulty gear. Utterly pointless. But more deaths were coming…Later in the summer, a BASE jumper, Ammon McNeely, snapped one of his legs in half when his chute failed to deploy properly. He somehow managed to video the entire event and its inevitable gruesome outcome. The jumper survived and the video, of course, went viral. His friends and followers wished him well from the soulful depths of facebook. Seeing a smiling photograph of McNeely and his partner, a fellow jumper wrote, “There is nothing cooler than having a girlfriend…who will jump off a building with you! Have fun dudes.”

One of the first on scene to aid McNeely was his friend and fellow BASE enthusiast, Daniel Moore. A month later, Moore would be dead. On November 24, during a routine jump along the river road, he lost stability as he leapt from a ledge above the Colorado River and was seen flailing his arms wildly as he sought to recover. He reached for the chute release, missed, and tried again. The chute deployed but it was too late. Moore was dead on impact.

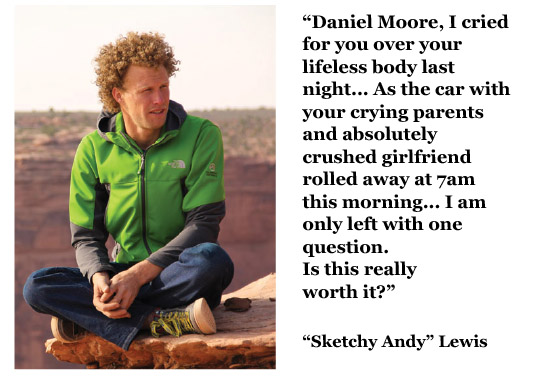

Moore died in front of his friend and mentor Andy “Sketchy Andy” Lewis. Lewis is an iconic figure to extreme recreationists around the world. I first heard of his highline stunts when he appeared with Madonna at the Super Bowl a couple years back. His notoriety and, to his followers, fame spread as quickly as a jumper chasing terminal velocity. Since then, Lewis has expanded his repertoire to include the most daring aspects of BASE jumping. And he has become a drawing card for Moab’s exploding extreme sports community and the latest component in its ever-expanding tourist economy.

Sketchy Andy Lewis is extreme sports’ mythic figure. But on the evening of Moore’s sudden death, a devastated Lewis shared his feelings with his 5000 facebook followers:

“Daniel Moore, I cried for you over your lifeless body last night. Gasping through tears in the beautiful fresh snow, i left you on the talus, too upset to help your body down. AS your best friend, i still can’t understand my weakness in the moment. I can’t believe how much I loved you, how much you inspired me, and I will forever live differently in my day to day life trying to be more like you were. Always happy, always positive, always full of life, spirit, and stoke. As the car with your crying parents and absolutely crushed girlfriend rolled away at 7am this morning… I am only left with one question. Is this really worth it?”

“Is it really worth it?” Lewis posed the question that I wish more recreationists and the friends and families that love them would consider. Thanks to the social media, sharing grief and the loss of a loved one is becoming a universal experience in the 21st century. As the months passed last year and one fatal accident after another made its way to the headlines, it was possible to experience the horror and the grief, but also the rationalizations and the explanations and the justifications for the risks they pursued. Friends and lovers and mothers and brothers sought comfort in assuring themselves that they died, “doing what they loved.” That their deaths exemplified their “free spirits.” That to live more cautiously would be a denial of “who they really were.”The outpouring of support for Lewis after Moore’s death on his facebook page was heartfelt but diverse. One young mourner wrote, “It was one f–king hell of an exit brudda! Footage can attest. RIP Daniel: His legend lives and loves on.” Another quoted Helen Keller who once observed, “Security is mostly a superstition. It does not exist in nature, nor do the children of men as a whole experience it. Avoiding danger is no safer in the long run than outright exposure. Life is either a daring adventure, or nothing.”

Another quoted Helen Keller who once observed, “Security is mostly a superstition. It does not exist in nature, nor do the children of men as a whole experience it. Avoiding danger is no safer in the long run than outright exposure. Life is either a daring adventure, or nothing.”

And many others assured Lewis that, “ he’d want us all to keep living life to the fullest” and wondered if “you or us (would) be the same person/people if we didn’t push our life’s limits.”But one father urged Sketchy Andy to heed his own warning. He pleaded, “This breaks my heart. I’m assuming an accident from some extreme sport. Andy, keep asking yourself the question, ‘is it worth it?’ Chasing adrenaline highs has the potential to lead us here. I fear daily that I’ll get a call about my son needing to be picked up from the bottom of a canyon or from the morgue. Nothing, nothing will break a parent’s heart more than the loss of a child. I pray for his family and you all, his friends. So sorry for this loss.” Finally one person said simply, “We are all here on borrowed time. Each moment is precious.”

Exactly. Just how precious is that moment, leaping from a 1200 foot cliff, when suddenly everything goes terribly wrong and, as the ground comes up to meet you at over 100 miles per hour, you know this moment is your very last? Is it worth what you’re about to lose?

Let me tell a story. When I was almost 20, like most young men of that age, I had no sense of my own mortality. Death was an abstraction. It’s true, a few years earlier, I had lost a cousin in an auto accident. JB wasn’t wearing a seat belt and was thrown from the car. His body hit a stop sign and he died instantly. But we weren’t that close and I didn’t feel a great personal loss. It couldn’t happen to me.

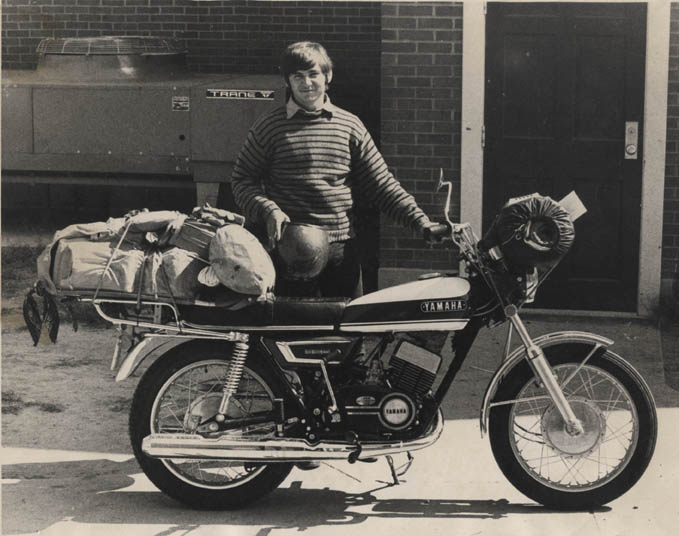

Then I quit school, sold my car, bought a Yamaha 350 2-stroke cycle and headed west from Kentucky. I’d even bought a red metal-flaked Bell helmet, not for safety concerns, but because I thought I looked so damn cool in it. Exactly four weeks after I left home, I was driving north on Broadway in Santa Maria, California at about 45 mph, looking for a place to eat. A southbound car suddenly turned left, in front of me. I didn’t even have time to brake.

I plowed into his right front fender, sailed over the handlebars, hit something hard, then went flying through the air. I was doing horizontal cartwheels and was facing straight up at the early evening sky. I still recall the color of that sky. Two distinct thoughts crossed my mind: “I wonder how long I’ll be up here?” And, “I hope I don’t hit the stop sign.”

I plowed into his right front fender, sailed over the handlebars, hit something hard, then went flying through the air. I was doing horizontal cartwheels and was facing straight up at the early evening sky. I still recall the color of that sky. Two distinct thoughts crossed my mind: “I wonder how long I’ll be up here?” And, “I hope I don’t hit the stop sign.”I came down hard, more than eighty feet from my bike. I could see my mangled 350 under the wheels of the Buick. One kid, my age, got me a blanket and a classic gawking crowd began to form. Within minutes I heard the sirens. A cop pushed his way through the bystanders and stopped in his tracks when he saw me.He shook his head and said, “Damn kid. You should thank god you’re wearing that helmet. You shattered his windshield with your head. You should be a DOA right now.”

That’s exactly what he said. I ended up in surgery with a shattered leg and to this moment, right now, it hurts like hell. But I’m alive. And not because I was trying to be cautious or careful. But because of a red helmet that I thought might impress the girls. Dumb stupid luck. I got a second chance that I didn’t deserve.

Decades later, I was wandering through a remote cemetery in a little village in Western Australia. A gravestone caught my eye. On it was the name of a young man—he had been a young man when he died—who shared the same birthday as me. Same day, month and year. He had died at 23, just a few years after my own near-miss. How he died, I couldn’t say. The grave looked neglected, as if no one had been to visit it in years. Decades had passed since his passing, other lives had moved on, memories had faded. The connection was lost, as it must be lost if we are to survive these kinds of tragedies.

And it made me reflect on my own life and that moment so long ago, at the junction of Broadway and Williams in Santa Maria. I thought of the future I almost missed, of friendships never made and heartbreaks never endured and memories never created. I thought of the stories I would never hear or be able to share. I thought of sunsets never seen and popcorn never consumed and journeys never made and epiphanies never discovered and computer glitches and flat tires never cursed over, and failures never pondered And I thought of a soulmate I would never have found.

So, is it ‘worth it’ to give up a life? Your own life? So soon?

Your choice…your call. But for me, I’m so damn grateful I got to stick around.

Jim Stiles is Founder and Co-Publisher of the Canyon Country Zephyr.

To read the PDF version of this article, click here.

To comment on this article, scroll to the bottom of the page.

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!

Similar thoughts crossed my mind when I read about this young man’s death — and the accidents/injuries that others in his circle of friends have suffered. I must not have that “danger gene.” Certainly, not to the same degree. I don’t much care for heights; on the other hand, rappelling is a rush, and canyoneering is pretty cool. So, is it just a matter of degree? We all like the excitement of certain outdoor activity, but I get plenty of excitement without leaping off a canyon wall or slack-lining high above a canyon floor. I, too, survived my youthful stupidity or excesses. I hope these “extreme sports” fans do too.

Great article, Jim. I have often had similar, but less eloquent thoughts. I made a good living in adventure travel for many years, and never bought into the concept of beating Mother Nature. I’ve always thought we should try to respect and travel in harmony with nature. I also think it’s sad, but probably inevitable, that each new generation thinks they invented the concept of pushing the envelope. Finally, I am reminded of the old saw I used to tell my new guides that I first heard from my buddy Phil, once a Moab-based guide: “There are old guides, and there are bold guides, but there are no old, bold guides.” Again, thanks for an eloquent and thoughtful piece.

It’s well known among alcohol and drug counselors like me that addicts under about age 30 are much harder to reach. The high they get from smoking crack or snorting opiate pain pills is so amazing that they can’t conceive of living without it. Bad things have to happen to them, usually a lot of bad things, before they’re willing to seriously consider that question: is it worth it? In the end, some of them do.

There may be a comparison to extreme sports here.

We’ll said…the truth of this article is head on and heartfelt.

-a grieving dad.

Thank you, JIm, for a well written essay on this subject. I just saw a TV ad for something that had film footage of a similar stunt to swinging through Corona Arch. The unsaid message is-buy this and see the thrills you’ll have!

How sad and yes, potentially narcissistic. The sense of wonder we can have discovering natural areas just isn’t enough for some folks.

What really bothers me is the almost universal statement attributed to yet another extreme athlete as follows: He did not feel like he was alive unless he was living on the edge. The thing is in many if not most cases the dude left a young wife and child/children, along with parents siblings and others. So for truly extreme selfish reasons another guy dies because he had to have that rush but then he isn’t living in any form for the family he left behind. Step away from the edge and live longer, it isn’t worth it!

Jim I had a fellow motorcycle riding high school classmate killed on an RD 350 in ’73. I rode a Suzuki T500.

“Noah” was killed by an 80 yr old friend of my parents who pulled out in front of him while Noah was going about 75 mph right in front of his parents house. The old guy driving never even saw him at all. I was shook up enough to sort of calm down on my own bike and I survived that chapter. We all knew Noah lived on the edge.

Jim,

I often think how lucky I feel to be part of the generation that thought just biking Slickrock or running a rapid was an extreme sport. The bar on what is considered extreme seems to be raised with each crop of young thrillseekers. I made it through the trials of my day that were required to be cool (at least I thought so), but there seems to be no end to what our young imaginations can conceive. Thank god I’m old!

Thanks for the Life inspiring words. One of the best pieces you’ve written! My life has got a whole lot safer since I’ve had kids and I will do everything in my power to prevent them from pursuing extreme adventure. I’m like you, I don’t feel the need for the adrenalin, not to say that I didn’t do stupid, dangerous things, it just wasn’t for the rush. Once I was accidentally forced off the road out by pack creek ranch on my motorcycle and came inches from going into a boulder strewn ditch 10 feet below, doing 60! My life flashed before my eyes. It scared the shit out of me and that was it. I sold the damn thing. I’d rather take a quiet walk out to some remote cliff edge and just gaze. I have no urge to jump off. I just use my imagination to feel what it must be like to fly. I’m so grateful I lived to have children and share camping and hiking and gazing up at the stars with them!

Your comments are all true, especially “is it worth it?” I was a skydiver beginning in late 1966, earning my B-rated license in April, 1967. The founder of B.A.S.E. jumping is Carl Boenish, who I jumped with many times back then when he was just a skydiver. I went to the World Parachuting Championships in Bled,Yugoslavia, with Carl and his jump team in 1970. Carl died in 1984 in Norway jumping from the Troll Wall. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carl_Boenish

I often think back — is it worth it? I doubled malfunctioned in Bled and sold all my gear over there, and then returned to the southwest to river guide the Grand Canyon. Best decision I ever made.

What an excellent piece of writing. I’ve been enthralled with watching videos of BASE jumpers and wingsuit flying over the past couple years. But when Steph Davis lost her husband in a wingsuit flying accident in Italy and as more deaths continued stacking up as you mentioned and now Dean Potter, I do not care to spend my time watching these extreme sports anymore. No amount of pleasure derived from doing such daredevil activities is worth risking one’s life. There is so much more to life than a risking it all for a pursuit of passion.

So much handwringing over extreme sports–especially in light of Dean’s death. It’s a shame we can’t spare a little of the same for, say, the 40,000 Americans killed in automobiles per year–guess that’s just American exceptionalism… or the thirty thousand who guy from gunshots…

Potter lived more in a month that most who make it to a hundred.

I wonder if growing up and expressing the fullness of life—raising a family and doing meaningful work—look even less possible to my son’s generation than it did to mine during the ’60s and ’70s. Ultra-thrills could easily be a reaction to despair.

My kids grew up where they were born, in Aspen. They have highly specialized skills on skis that they trained and drilled for. My boy’s been on rocks and climbing walls since he was little. I get all that. If I was 20 again and the equipment and opportunity were handy, I’d do sky sports, too.

But there’s a passive culture of suicide in some behaviors of the early-adopters and bleeding-edge brahs that go for rock-star legendary status.

I’d just like to point out that the dudes who invented freestyle climbing in Yosemite are all alive. Chouinard, Robbins—those guys. Dying was not cool.

Very well said. Many nature enthusiasts like an occasional physical challenge, preferably with health benefits. When an “extreme” challenge crosses the line of reasonable risk and becomes an end in itself, however, love of nature gives way to narcissism. Base jumpers and extreme climbers appear to crave attention more than they love nature.

I confess to ambivalence about this glut of tragic deaths from extreme sports. There are 7 billion humans on this planet now, so if a small percentage of them want to defy the odds and risk their lives, so be it. There have always been daredevils among us, going back to the bull jumpers at Knossos, and surely far beyond that in the past. I do admire their daring, and their pushing the limits of what humans can do.

I have flipped in class IV rapids, and experienced that horrible feeling in free climbing — that I couldn’t go up and couldn’t go back down. I did it a few times and that was enough — there is too much else in life I want to accomplish and experience. So for me, persistent risk was not worthwhile.

The key point with extreme athletes like Dean Potter — for them, it becomes a career, as they are subsidized by corporate sponsors, thus encouraged to keep pushing the odds, maintaining their visibility… until the odds eventually catch with them — just as they do with addicted gamblers in Vegas. It’s more than just the adrenaline addiction. The corporations encourage this excess as a means to promote their products.

A video was published on Youtube on April 7, 2015 showing a new type of base jumping (from a net suspended over a canyon). The description of the video mentioned the death of Daniel “Money Making” Moore and said, essentially, the jumping was in dedication to him. For whatever reason, the Youtube algorithms thought I should see it today. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bCT8WWVpitU There wasn’t much in the description about Daniel, so I looked around to find out some more, and your article came up. I found it thoughtful, and well written.

Based on the video I saw however, I feel that anyone who could have benefited from your advice either didn’t read it, or wouldn’t have been persuaded by it even if they had. You can lead a horse to water…

It’s odd when people lose someone in an “extreme” activity and then decide the best thing to do is to honor that person is repeat the extreme activity that killed them. It’s like the people who lose a friend riding a motorcycle, so they decide to have a mass motorcycle ride in honor of them.