I’m not sure what else can be said about Edward Abbey after all these years. God knows I’ve said plenty and have often tried to speculate ‘What Cactus Ed would’ve done,” as we race through the second decade of the 21st Century. What concerns me, I admit, is the inability of so many latter day Abbeyphiles to consider how he might react to the world we face today, had he lived to see it. For so many, not only is Abbey frozen in 1989, the issues are as well. To suggest that he would have turned a blind eye to changes even Ed might not have expected a quarter century ago does him an injustice.

Many of the issues he felt so passionately about seem, at first glance, to have changed little since he left us in 1989. Consider ‘wilderness.’ It’s been a half century since Abbey first wrote so passionately and eloquently about the subject. He once selflessly suggested, “We need wilderness whether or not we ever set foot in it.”

In ‘Desert Solitaire,’ Abbey also offered this unique proposal:“The wilderness should be preserved for political reasons. We may need it someday…as a refuge from authoritarian government, from political oppression. The Grand Canyon…may be required to function as a base for guerrilla warfare against tyranny.”

Whether the revolutionary guerrillas could find common ground with BASE jumpers, mountain bikes, ‘adventure companies,’ and Corona Arch Swingers is debatable. The “excessive industrialism” he feared has been more insidious than even he imagined, despite his own early warnings about “industrial tourism.” His notion of wilderness would perplex most 21st century wilderness advocates who insist that its commercial exploitation via a “tourist/amenities” economy will generate untold revenues for the Rural West.

It is certain that, twenty-five years after Abbey left us, saving wilderness for its solitude, remoteness, and as a base camp for revolutionary warfare, is not high on anyone’s agenda.

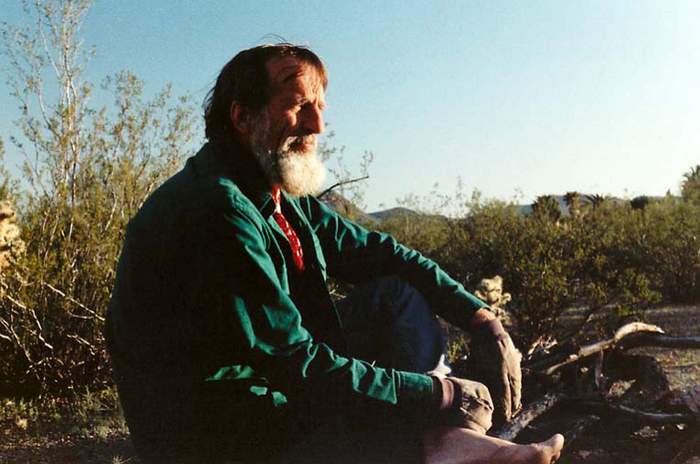

Abbey lived in Moab for many years, but in 1980 he decided to make a move to Arizona. In early May I drove out to say goodbye and found him alone, wresting a piano into a U-Haul truck. I offered a hand and we spent the rest of the day grappling with the remainder of his furniture. Almost everything fit, but he eyed a long pile of heavy lumber and complained, “I guess I’ll have to leave all that behind.”

“What’s it for?” I asked.

Abbey grinned, “To build my adobe houseboat on Lake Powell. Remember? I don’t make everything up.”

Afterwards, Abbey invited me to join him for dinner at the old Sundowner. We ordered a red wine and big Porter House steaks and talked about Moab’s future. Recently, uranium prices had plummeted and the nearby Atlas Mill was shutting down. What would happen to Moab next? Neither of us had a clue.

The wine came. But the waitress had placed the bottle in a bucket of ice cubes. Quietly he moaned, “For Christ’s sake, typical Moab. Don’t they know you DON’T chill a red?” As we sipped our icy drinks, Abbey softened, “I can live with an icy red. But leave our canyons alone, eh Stiles?”

Barely a year before he died, Abbey spent his last summer in Moab. I took him to the Sand Flats one day to see the re-discovered “Slickrock Bike Trail.” Moab was on the verge of being transformed—transmogrified is more like it—into the “Mountain Bicycle Capital of the World.” But Ed, at first, came to the bikers’ defense.

“I like bikes,” he complained. “You’re more negative than I am!”

“Well, “ I defended myself. “Have a look first.”

We drove his old Ford truck up the switchbacks above town and saw the hordes of pedaling recreationists who had made the Moab Pilgrimage. We watched the crowds overflow the parking lot as the bikes fanned out, like a thousand spiders, over the vast sandstone expanse; Abbey noted some of the cars and license plates–-lots of BMWs and Saabs and Audis. Many California plates…Marin County.

Ed shook his head. “I had no idea.” And he flashed back to our conversation of almost a decade earlier.

“One thing’s for certain, “ Ed sighed. “When these people drink a red, they’ll know not to chill it.”

Abbey thought of bikes as a way to replace cars, not feet. This was something new. We crept down the switchbacks in silence. The next day Ed drove south in that battered Ford F-150 of his, back to Tucson. He never got back to Moab.

Twenty-five years after his death, Abbey’s ‘wilderness,’ has lost some of its poetry; it was, in fact, Cactus Ed who once swore that the movement “needed more poets and fewer lawyers.” Today, the canyon country is fought over by two opposing forces–one wants to exploit its energy resources; the other half wants to exploit its beauty for tourism dollars. Now Abbey’s option—just leave it like it was—-is but a quaint reminder of a time that never existed.

His last glimpse of the slickrock was our first glance of a future we never imagined. When Ed said, “What our perishing republic needs is something different…something entirely different,” I don’t think this is the future he had in mind.

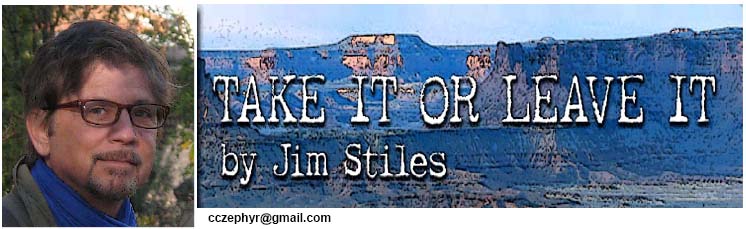

Jim Stiles is Founder and Co-Publisher of the Canyon Country Zephyr.

To read the PDF version of this article, click here.

To comment on this article, scroll to the bottom of the page.

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!

I think “something entirely different” is another paradigm, the one that so many think is impossible.

Amid their own greed, those wealthy American recreationalists are the ones who give money to the conservationists who then fight on the steps of capitol hill to keep bike and hike trails open to the public. I’d say Abbey’s issue with the American Way of Life goes way beyond the Sand Flats!

Great piece.

A sustainability movement where the rights acts would include evaluating the entire life cycle of actions from a future perspective to see if the planet can endure. Abbey always made me feel that was possible, never too to late to imagine that world and work to make it come into reality.