BEGINNINGS…1988-1996

Here’s how far we’ve come.

Shortly after The Zephyr’s first issue appeared on newsstands, in mid-March 1989, I was at the old Main Street Broiler, eating one of Debbie Rappe’s wonderful cheeseburgers and overheard a spirited conversation at an adjacent table. “This smart ass kid thinks he can just start a newspaper and then tell us how to live! His ‘Zephyr’ garbage won’t last three months.” His friend nodded, “I hear he’s one of those environmental weirdos.”

Jump ahead—way ahead—to the day last year when I found this post on our web site; it was in response to a story on extreme sports. “It’s this geriatric community of do-nothings,” young Seth complained, “that wants to sit by and look at rock that is getting butt-hurt…It’s so sad watching you get old and bitter.”

From smart ass kid to old and bitter. Seems like only yesterday.

Back in 1990, when somebody asked Grand County Commissioner Jimmie Walker what he thought of the new publication, Walker grinned and said, “I can sum up The Zephyr in one word…SHIT.” And in 2012, Grand County Councilman Chris Baird described The Zephyr like this: “ You are like a flesh-eating cannibal…But vultures will be vultures.”

Back in 1990, when somebody asked Grand County Commissioner Jimmie Walker what he thought of the new publication, Walker grinned and said, “I can sum up The Zephyr in one word…SHIT.” And in 2012, Grand County Councilman Chris Baird described The Zephyr like this: “ You are like a flesh-eating cannibal…But vultures will be vultures.”

On the other hand…

Almost a quarter century ago, one reader had this to say about our new publication: “Stiles is an aggressive perpetrator of knowledge, a passionate defender of kindness and common sense, and has a splendid sense of humor…The Canyon Country Zephyr might be the best local newspaper in the country.” But a local realtor disapproved: “Stiles wants to return to the good old days of Ed Abbey and economic depression. He has a closed mind when it comes to progress.”

In 2013, one reader left this comment: “Stiles is a fount of unending negativity. I can’t believe it hasn’t killed him yet.” But another reader expressed a different sentiment: “Thanks for your eloquent writing.” And she thanked me for “the much-needed voice of the CCZ.”

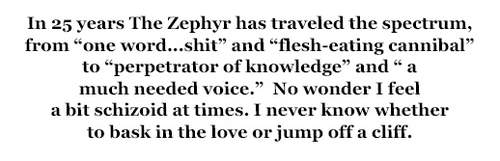

In 25 years The Zephyr has traveled the spectrum, from “one word…shit” and “flesh-eating cannibal” to “perpetrator of knowledge” and “ a much needed voice.” No wonder I feel a bit schizoid at times. I never know whether to bask in the love or jump off a cliff. Fortunately, most of the time, I’ve chosen to do neither. One thing is for certain, as we enter the 26th year of life, very few people who read The Zephyr are ambivalent about it. And though this rollercoaster has almost broken me a couple of times, it’s a journey I’m grateful to have been a part of. It’s been quite a ride.

BEGINNINGS…1988-1996

In the waning days of 1988, Moab was a different kind of place; so was the world. I was months way from publishing the first issue of a new publication I had recently decided to call, “The Canyon Country Zephyr.” I’d kicked a few less memorable names around, including ‘The Slickrock Journal” and “The Moab Monthly.” But driving along Mill Creek Drive, near Emmit’s K-D Second hand Store, ‘Zephyr’ popped into my head. It stuck.

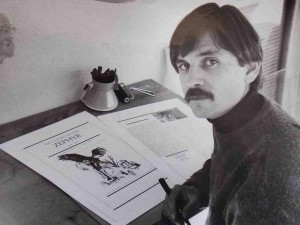

I had recently been writing and cartooning for Bob Dudek’s irreverent monthly, “The Stinking Desert Gazette.” The Gazette had been around for a couple years and Bob had offered me work when his cartoonist Nik Hougan briefly moved north to run the family’s farm in Idaho. I needed the money and was intrigued with the idea of being part of a newspaper. I had earlier quit my seasonal ranger job at Arches National Park, after the death of a co-worker and very close friend. Though the details of that tragedy are not suited for this story, its sordid and ugly aftermath would affect me and this publication for years. Later in this narrative, I’ll explain how.

The Gazette was my introduction to newspaper production, 1988-style, and I enjoyed it. My role there grew and soon I was submitting stories and essays as well. I liked Bob and the gang who had been a part of the SDG since its inception, but Dudek and I were not a good fit. I think Bob enjoyed exploring the absurdity of Moab more than me, even then, and he avoided embracing the hard news stories. He once told me he wanted the SDG to become the “MAD Magazine of the Desert,” and I think he could have succeeded. Meanwhile I kept trying to slip serious stories about Moab politics into Dudek’s off-beat, funky rag. He always printed them and was consistently patient with my aberrations. But ultimately, for me, it didn’t work, so I gave my notice in September 1988.

My first thought was to pursue a reporter/cartoonist job with an environmental magazine like ‘High Country News,’ but opportunities then were far and few. I was even offered a seasonal job with the Park Service in Alaska by an old ranger buddy. But in November, when Grand County citizens voted to stop a toxic waste incinerator, it occurred to me that Moab could use another news voice, besides the weekly ‘Times-Independent,’ Grand County’s newspaper ‘of record’ since 1896.

Read: “The Calm Before the Swarm…part1″

Read: “The Calm Before the Swarm…part 2”

Read: “The Calm Before the Swarm…part 3”

The town was in dire straits; the uranium industry had collapsed, hundreds of jobs had been lost, and a quarter of Moab’s homes were empty and for sale. Moab’s ‘survivor’s were trying to figure out ways to keep their heads above water. Oddly though, because we were all in such a bad way, there was also a spirit of community and togetherness. It was that feeling that convinced me a monthly alternative could make it, as long as I kept it simple and my ‘business plan’ cheap.

And it was also my hope that it could be a gathering place for divergent ideas. From issue one, I was determined to offer all points of view. Not only would I welcome constructive criticism, I would seek out different viewpoints as well. I found Raquel Shumway, and later Jane S Jones, to represent the Western Alliance of Land Users to counter the monthly contributions of the Sierra Club and Lance Christie. The ‘debates’ that were waged in this publication 25 years ago still make for interesting reading. My hope was that we could at least remove the demons from the debate. We didn’t have to hate each other if we shared different philosophies. I know that’s an idealistic and maybe even simplistic approach. I know also that sometimes different values are irreconcilable. But if there was common ground to be found, I hoped it might be in The Zephyr.

I hit the streets in January 1989, looking for advertisers and did better than I’d expected. Still, at $18 for an eighth-page ad and $31 for a quarter, including art work, few could refuse. And when possible, we bartered…trade-outs were big in Moab in 1989. Even preferred. A few years later, Bill Hedden would note that Moab had been, “a hard place to get rich but a good place to be poor.” He was exactly right.

I also managed to convince almost a hundred friends to buy a $10 yearly subscription. I found a good printer in Cortez, Colorado. Larry Hausman, the head press man, explained the process and he looked over some of my dummy cut and paste pages. Now all I had to do was put together a newspaper.

APPROACHING VOLUME 1 NUMBER 1…

MARCH 14, 1989 & ED ABBEY

In early 1989, Moab was still buzzing from the November election. Grand County citizens had approved a measure to stop a toxic waste incinerator and had thrown two of its incumbent commissioners (and  incinerator proponents) out of office. But the vote against toxic waste had crossed demographic lines; an interesting and diverse groups of Moabites had united to change Moab’s future. At the time, it felt like a new beginning for Moab. I figured, what better way to keep this spirit alive than to create an ongoing dialogue with the new commissioners. I contacted incumbent Dave Knutson and newly elected commissioners Fern Mullen and Merv Lawton. All were agreeable to a monthly sit-down with The Zephyr, on tape, to discuss current issues. Later Mayor Tom Stocks also agreed to a spontaneous monthly, on the record interview.

incinerator proponents) out of office. But the vote against toxic waste had crossed demographic lines; an interesting and diverse groups of Moabites had united to change Moab’s future. At the time, it felt like a new beginning for Moab. I figured, what better way to keep this spirit alive than to create an ongoing dialogue with the new commissioners. I contacted incumbent Dave Knutson and newly elected commissioners Fern Mullen and Merv Lawton. All were agreeable to a monthly sit-down with The Zephyr, on tape, to discuss current issues. Later Mayor Tom Stocks also agreed to a spontaneous monthly, on the record interview.

In December, Ed Abbey made what would be his last trip to Moab. While he signed copies of “Fool’s Progress” at Ken Sleight’s book store, I told him about the proposed Zephyr. Abbey was delighted and later, as we sat in my VW Squareback, sipping beers, he offered to send something for the first issue. “I want to put an original story in your Zephyr,” he said. “Maybe I can become one of your regular corespondents.”

I’d already circled the first ‘press day’ on my calendar and so I told Ed, “March 14 is what we’re hoping for.”

Abbey replied, “I’ll get you something before then.” We shook hands in the cold December darkness and I watched him amble away in his long, loping walk. I figured I’d see him next Spring.

Trying to put a newspaper together posed a problem. I didn’t have a computer and I didn’t know how to type (I’m still awful slow). To say this was a shoe-string operation, even then, would be an understatement. But my friend, attorney Bill Benge, proposed that I use his computer and his secretary Trish West moonlighted as my transcriber. Beginning with the first issue and for three years, everything I wrote was hand-scribbled on yellow legal pads and left to Trish to interpret. Even long interviews with the politicians were hand-transcribed by me and passed to Trish.

We were also in need of a printer and Trish’s uncle, CPA Ed Claus, graciously allowed the use of his when we were ready to lay out pages. His printer had one postscript font—helvetica bold—and so for three years we used this thick bold eight point type for stories and essays and interviews. I hand-scribbled the headline type and ad copy too, with size and font instructions, and took it to the Printing Place, where Larry and Marge Fleenor punched out the copy on a photographic ‘Compu-graphic’ machine. From there it was all cut and paste. More precisely, the entire paper was held together with hot wax. My hand-held hand waxer would serve me well for the next 17 years.

In 1989, emails didn’t exist. No cell phones. We depended on 51/4 inch floppy disks (they really were floppy) to print some stories, but most of them had to be re-typed. It was a long process.

With my first deadline fast-approaching, I began to write and gather stories. The first issue included interviews with both the commissioners and the mayor. We ran original stories about asbestos-dumping in Grand County and a report on local child abuse. I wrote a piece about my next door neighbor called, “Toots McDougald’s History of Moab,” and featured local artist Kathy Cooney on our first “Zephyr Gallery” page. Ken Sleight and John Sensenbrenner (the owner of Milt’s ‘Stop n’ Eat’ in the 80s and 90s) offered opinion and analysis from the Left and Right. Even my mother got into the act with “Grandma Sue’s Country Kitchen and her recipe for Mock Turtle Soup.

Abbey’s story arrived in mid-February, and with a note from Ed. He had sent me a never-before-published essay called, “Hard Times in Santa Fe,” but he hadn’t written it exclusively for The Zephyr. He’d been busy finishing his sequel to ‘The Monkey Wrench Gang’ and was trying to beat a deadline. We would learn soon that the deadline was for more than his latest novel.

A couple days before I carried the layout boards to Cortez, I’d heard a rumor that Abbey was ill. The same rumor had hovered over us for years, in fact, but Abbey had always kept his health issues private. In January I called the Abbeys and learned he’d had “an episode,” but was on the mend. So at 5 AM on March 14, 1989, I packed the layouts and my check book into my 1963 Volvo and drove the 120 miles to Cortez News. It took about five hours to produce Volume 1 Number 1. I worried about typos and scrambled layouts, knowing that once it rolled off the presses there wasn’t a damn thing I could do to fix them. By noon, The 2000 Zephyrs were printed, boxed and loaded into my Volvo. The trunk and back seat and passenger seat were stacked to the ceiling. I barely had room to sit.

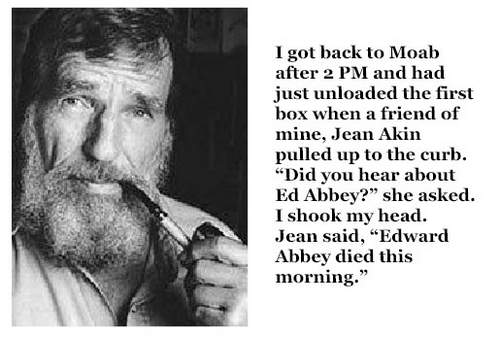

I got back to Moab after 2 PM and had just unloaded the first box when a friend of mine, Jean Akin pulled up to the curb. “Did you hear about Ed Abbey?” she asked. I shook my head. Jean said, “Edward Abbey died this morning.”

I couldn’t believe it. I was absolutely paralyzed. That afternoon, my great friends, the Knouff family–Becky, Kate, Terry and Tim— helped get the first issue on the newsstands. I headed out to Pack Creek Ranch to spend the evening with my buddy, and one of Abbey’s best pals, Ken Sleight. A few days later, Benge and I drove down to Tucson for the private memorial service. Bill had been Abbey’s attorney when he lived in Moab and had, in fact, written much of the last chapter of ‘The Monkey Wrench Gang,’ after they finally got caught. Abbey was a writer not a lawyer, and Bill helped fill in the blanks on courtroom procedure and the rule of law. We gathered at Saguaro NM west of town. It’s a blur now. It was a hard day.

Later, Benge and I made the long 17 hour drive home. Two days later, I had to put my 15 year old dog to sleep. I was ready for that week to be over.

In late May, a larger public memorial service was organized by Ken Sleight, Ken Sanders, Terry Tempest Williams and me. My job was to find a site for the event. I inquired about a location at Arches but when I was hit with permit applications and fees and a requirement to provide port-a-potties, I decided Abbey would prefer a different venue. I finally picked a site on the mesa above Arches but outside the park. To get there, everyone had to drive the old abandoned road to the top of the canyon and then walk the last mile. In the early hours before the service, I couldn’t sleep and so I drove up Moab Canyon at three in the morning to watch the night sky. All through the night, a slow but steady stream of car lights climbed the old road. Mourners came from all over the West, from all over the country. By the time the service began, a thousand people had come to say goodbye to Edward Abbey.

Ken Sleight was there. Doug Peacock. Dave Foreman. Terry Tempest Williams. Perhaps Abbey’s best friend, John DePuy, was too moved to speak. Later in the afternoon, I took Foreman to my favorite spot at Arches—Abbey’s Arch, the rock span Ed had found in 1956 and that I had re-discovered 20 years later. Less than a week after our hike, Foreman and other Earth Firsters! were arrested in a government sting operation.

A decade later, Abbey’s Arch would become (for a while!) a popular destination for a commercial canyoneering company and the old abandoned roadway up Moab canyon was converted to a paved bike path. All of that, however, resided in the future. In 1989, I had no idea what was coming…

THE BOOK CLIFFS HIGHWAY

In the early 1990s, one story dominated Grand County news. When the incumbent commissioners were defeated in November 1988, they still had a couple months to serve. In that time as lame duck officials, they created the “Grand County Roads Special Service District.” It was to be an independent government entity, funded by state mineral lease monies. They were, in effect, autonomous. And their stated goal was to build a multi-million dollar road over the Book Cliffs. Its real purpose was to provide better access for oil and gas development, but to make it more sell-able, they pushed the road as a new paved state highway that would dramatically increase tourism to Grand County.

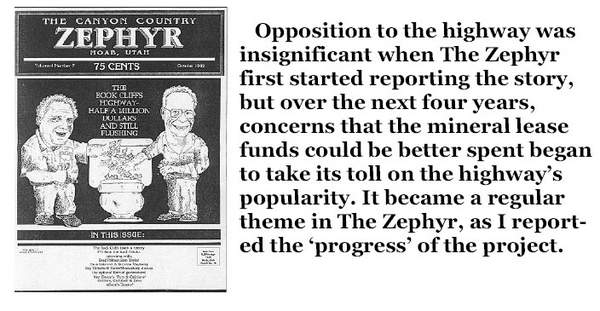

Opposition to the highway was insignificant when The Zephyr first started reporting the story, but over the next four years, concerns that the mineral lease funds could be better spent began to take its toll on the highway’s popularity. It became a regular theme in The Zephyr, as I reported the ‘progress’ of the project. Exclusively using mineral lease funds for the highway meant that money couldn’t be used for anything else. While the road board insisted it could ONLY be used for roads, a close reading of the law proved otherwise.

And yet, during that same period, I got to know and like one of its strongest and most honest supporters, Commissioner David Knutson. Knutson was the youngest member of the commission and his father Ollie was on the road board, so you wouldn’t think Dave and I would have found much in common. And yet we hit it off, despite our differences. The Knutsons ran an oil well maintenance company and wanted to see the roads in the Book Cliffs improved. It seemed like a conflict of interest to me; clearly they looked at it differently. Our disagreement on the issues made for some long and interesting arguments. The Knutsons frequently hauled water for the Park Service to the Hans Flat ranger station and residences at the Maze District of Canyonlands. I once rode along with Dave, four hours out, four hours back. We never stopped talking except to unload the water.

But it was the first time I realized how difficult it would be to play the role of journalist with people that I liked. A big city reporter can bury himself in anonymity and never have to face the people he scrutinizes. A small town journalist lacks that comfortable distance. He has to face his topics. That’s how it was with David. In the 1990 county elections, David faced opponent Dave Bierscheid, another longtime Moabite and also a good guy. Bierscheid also opposed the highway, so naturally my vote went with him. On election night, Knutson won handily and the returns were interpreted to mean a clear victory for the Book Cliffs Highway as well. But when he asked me who I’d voted for and I told him ‘the other guy,’ I sensed that I’d really hurt his feelings–that I’d somehow betrayed our friendship. And as strongly as I opposed the highway, I felt bad as well. Had it not been for the highway issue, I might have voted differently.

In the aftermath of the election, Knutson and the other winner, Manuel Torres, took their victory as an absolute mandate. Some, including me, thought they’d allowed the win to go to their heads, and my friendship with Dave cooled. The Zephyr interviews ended and, in the next two years, as local opposition grew, David and Manuel became more intractable.

My greatest frustration was the commission’s continued support of the Book Cliffs Highway. The Road District board continued to push forward and it began to have an inevitability about it, even as more and more people doubted that the project could be constructed for the price they were claiming. Still David Knutson was convinced he’d prevail and laughed at his adversaries. He reminded opponents that the Utah constitution offered no recourse if you didn’t like an elected official. There was no recall process, no impeachment protocol. “All you can do,” he said, “is shoot us.” But, as it turned out, he was wrong.

Somebody, I don’t recall who, gave the Utah State Code a close read and discovered a loophole. It was true that the state offered no process for removing a person from office. What the counties’ citizens could do was change their entire form of government. The idea was stunning; it required the collection of signatures on a petition to force such a change. But once the movement gained momentum, it seemed impossible to stop.

What few remember though is why the referendum was really initiated and what the driving force behind it was. It was not the Book Cliffs Highway. Before 1990, all counties in Utah were composed of three commissioners. Two of them were elected to four year terms but one commissioner term lasted only two years. In that way, two of the three commission seats, and the balance of power, were up for election every two years. No one could ever hold absolute power for longer than that without approval of the voters. But the state legislature changed that in 1990, making the length of all three seats four years. So when Knutson and Torres won, there would no longer be the option of waiting just two years to vote again.

As to motive, while opposition to the road grew, it was the commission’s decision to appoint a friend as head of the Grand County tourist office that actually pushed many of the edge—but not me. It was a strange irony that the ‘change of government’ vote had nothing to do with the highway; it was about appointing Robbie Swazey. Some thought she would be ineffective in that position, which would have delighted me, and as the growing number of ‘New Moabites’ clamored for more professional tourist promotion, I found myself once again at odds with my own priorities—do I want the Book Cliffs road stopped? But at what cost?

I was surprised as voices of opposition to the Book Cliffs Highway grew. In 1989, virtually nobody seemed interested in stopping this project. At a public informational meeting, proponents easily swayed most of the audience and when Times-Independent editor Sam Taylor gave the highway his blessing, it almost felt like a done deal. But in the next four years, as the costs grew and as ethical questions arose, more people in Grand County began to question its feasability.

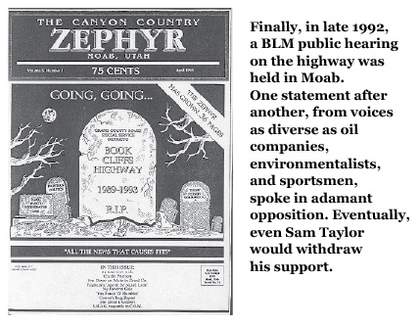

Finally, in late 1992, a BLM public hearing on the highway was held in Moab. One statement after another, from voices as diverse as oil companies, environmentalists, and sportsmen, spoke in adamant opposition. Eventually, even Sam Taylor would withdraw his support.

In November, the referendum prevailed. The ‘old government’ lost their jobs and in February, a special election created the first seven-person “Grand County Council.” It was supposed to be the beginning of a new era, and for a while it was. The following spring, the new council voted to dissolve the Special Roads Service District and re-allocated its funding to other county service districts that could use a revenue boost. It was–we thought–the end, once and for all, of the Book Cliffs Highway.

‘OLD WEST & ‘NEW WEST’—LOCKING HORNS in MOAB

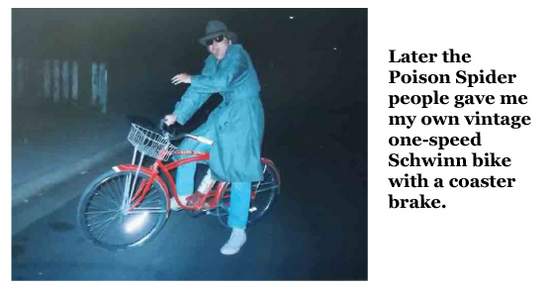

Those first seven years, when we put out a paper every four weeks, were the hardest I’ve ever worked and were the most gratifying. I spent a week out of every month walking Moab’s streets, talking to advertisers and whoever else I bumped into…actually, I can’t say I always walked. Once my buddy Anthony from Poison Spider caught me driving from the post office to Back of Beyond Books, a distance of 50 feet. Actually I’d forgotten I was supposed to visit the book store and swerved at the last moment to park. But I admit…it looked BAD. Later the Poison Spider people gave me my own vintage one-speed Schwinn bike with a coaster brake.

The monthly interviews were difficult but productive. I enjoyed the meetings and the conversations, but who wants to listen to politicians twice? That was what I had to do, of course, to transcribe them. The interviews lasted 45 minutes; the transcriptions five times that long.

I met many new interesting people who would write for The Zephyr, like Jack Campbell and Jane S. Jones and Rachel Shumway and Lance Christie. Even the ultra-capitalist Hank Rutter found a place in The Z. And in 1991, a fellow named Scott Groene introduced himself. He was the new SUWA (Southern Utah Wilderness Alliance) staff attorney and asked if he could contribute articles to the “canyon country watchdog” page. As you’ll read elsewhere in this narrative, Groene and I became friends and shared very similar concerns for southeast Utah, at least back then.

When we finally got computers in 1992 and I was trying to learn how to use the evil contraption, it was usually Groene who calmed me down when I couldn’t get a file to open and I thought I was on the precipice of the End of the World. “Calm down,” he’d say. “Hit Control D…better now”

If Scott and I had one difference of opinion, it was my un-shared fondness for at least aspects of the Old West…AND ‘Old Westerners.’ In July 1989, I’d written about wilderness and the rural west:

“I support wilderness in Grand County and Southeast Utah and that declaration alone can get a guy on more residents’ “enemies list” than anything else I can think of. There is no group more vehemently opposed to wilderness than the Western Association of Land Users. They oppose wilderness at all costs….With a few exceptions, WALU has no use for the likes of me.

“There was a time for me when the feeling was quite mutual. I regarded the anti-wilderness crowd scornfully. I had no use whatsoever for Ray Tibbetts who led the wilderness protest parade on July 4, 1980. Issues to me were very well-defined…very black and white. I was right and they were wrong.

“But during many of those years, I worked at Arches, lived at the park and really didn’t know the people who lived and worked in this town. All that changed six years ago when I turned in my badge and bought a house and eventually started this paper.

“And what I discovered, as I set up interviews, and researched stories, and walked Main Street looking for advertisers, was that many of the “enemies” I’d regarded warily all these years were (gasp!) kind, decent, honest people just trying to get by in this world. They were likewise shocked to see that I had no horns beneath my fedora either. I realized that they too long for quiet Sunday afternoons on Main Street.

“Since then, I’ve had to take another look at WALU, not for their political or environmental philosophy, but for who they are. For instance, how could anyone dislike Lilly Mae Norlander? I don’t care if she is against wilderness. She’ll never be an enemy of mine. Or Ray Tibbetts. We still don’t agree on development and wilderness, but we can talk for hours about the country we both love.”

In 1993, I wrote my first editorial that openly questioned the wisdom of a “New West.” I called it ‘New West Blues,’ and it resonated enough with editor Betsy Marston at ‘High Country News’ that she asked if HCN could re-print it. In the essay I wrote:

“This is not just another complaint about our changing town– the New Moab. What’s happening here is happening elsewhere. And what’s coming may be bigger than even we doomsayers would dare predict. Barring a miracle, we are about to enter a new phase, the last phase, in the taming of the West. When it’s over it won’t be “the West” anymore. We all know ‘how the West was won.’ What we are about to see is ‘how the West was done.’ To use a recently popular expression, pretty soon, you can stick a fork in it. And all of us, no matter how much we love the country bear responsibility.”

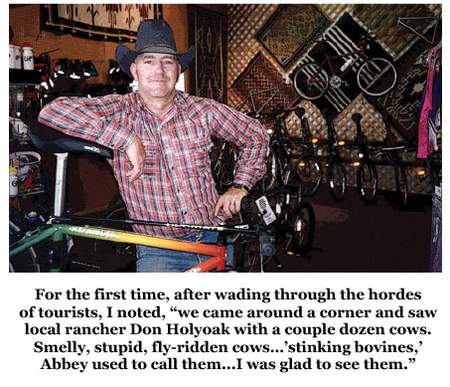

For the first time, after wading through the hordes of tourists, I noted, “we came around a corner and saw local rancher Don Holyoak with a couple dozen cows. Smelly, stupid, fly-ridden cows…’stinking bovines,’ Abbey used to call them…I was glad to see them.”

Many shared my conflicted feelings; others were not amused. My environmentalist friends loathed public lands ranching and the rural lifestyle, in general. It was a subject that Groene and I avoided most of the time.

I never changed in that regard; nor did Scott. He saw rural westerners as an impediment to his designated goal—to create a vast Congressionally-mandated wilderness for southern Utah, and in that regard, he was probably right. Early on, I could see a strategy just beginning to form in the minds of ‘progressive’ environmentalists in Utah—if you could change the demographics of these rural towns, you can change the attitudes. If you can create a new community that supports wilderness legislation, you can get the votes to do it. From a political and strategic standpoint, it was a completely logical, even brilliant idea.

Still it bothered me. One day, after talking to Lilly Mae, I expressed my worries to Scott.

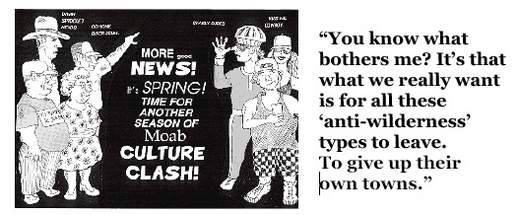

“You know what bothers me? It’s that what we really want is for all these ‘anti-wilderness’ types to leave. To give up their own towns.”

Groene stared out the window at the hummingbird nest that had been constructed on a nearby tree branch. Watching the young hummers was often preferable to arguing.

“The thing is, “I continued, “These are nice people, even if they don’t agree with us.”

Groene looked at me like I was Donald Duck. “What’s ‘nice’ got to do with anything? Our job is to create wilderness.”

“New Moab,” in my heart of hearts, was already an inevitability. For Scott and me, our views would both remain intractable when it came to the fate of the Rural West. And that hummingbird nest? A few years later, as the tourist economy boomed, the tree outside Groene’s SUWA office window was chopped down and another curio shop filled the space where the tree and the little park beneath it had resided.

THE REST OF THE STORIES..

There was always more to The Zephyr than ‘environmental issues.’ especially in the early years when we were a monthly and so closely tied to the community. I realized that, as small as our little rag was, it could make a difference from time to time.

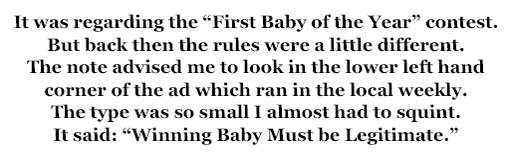

One day in late 1989, as I prepared to put the finishing touches on the last issue of the year, I received an anonymous note. It was regarding the “First Baby of the Year” contest, a tradition that survives today. But back then the rules were a little different. The note advised me to look in the lower left hand corner of the ad which ran in the local weekly. The type was so small I almost had to squint. It said: “Winning Baby Must be Legitimate.” Here is, in part, how I responded in the next issue:

“Leonardo da Vinci was a great artist, inventor and a genius. Sarah Bernhardt was a great actress. Alexander Hamilton was the first U.S. Secretary of the Treasury. What does this diverse group of people have in common? Their parents were not married when they were born. To use the antiquated vernacular, they are ‘illegitimate.’

If they were born in Moab, and if their birthdays fell close to the first of the year, all of them would be disqualified from the First Baby of the Year Contest, sponsored by almost two dozen Moab merchants. Each year, these sponsors award a variety of presents to the baby and the parents of the newborn. But the contest rules are explicit. The fine print reads: ‘Winning Baby must be legitimate.’

I’m by no means disparaging the institution of marriage, but doesn’t a new mother without a husband already have an enormous responsibility to bear alone? …I wish the sponsors could re-evaluate their position and take another hard look at the rules…If it happens again this year (it has occurred in the past) and the baby is disqualified, The Zephyr and a group of local merchants including: Pack Creek Ranch, Main St. Broiler, Moab Mercantile, Hogan Trading Co., Dave’s Corner Market, Four Corners Design, Rim Cyclery, The Movies and Moab Community Co-op will match the prizes intended for the baby. This is the time of year for compassion and generosity, not narrowmindedness.”

The sponsors of the event backed off, removed the stipulation and when the first baby of 1990 was born, she was the beautiful daughter of a working single mother. Sometimes, there is justice in this world.

There were other small victories. When we heard that the Moab Fire Department planned to expand its facilities on First East and cut down a 60 year old pecan tree, we came to the defense of the tree. The local ornithologist spoke up as well, saying the tree was vital to migrating raptors. And again, reason prevailed. The tree was spared. It’s still there.

One of the biggest boondoggles of the early 1990s was the proposed “Kokopelli National Theater of the Performing Arts.” It was to be the western version of Wolftrap, a large outdoor amphitheater and built on the Sand Flats above Moab, adjacent to the Slickrock Bike Trailhead. The idea was simple enough in the beginning, but then the ‘plan’ grew, and grew…and GREW. Zephyr columnist Jack Campbell was an early critic and fierce watchdog and reported often via his articles. As the years passed, the project began to lose support and eventually died from a lack of funding. Still, I’ve always believed that Jack’s columns played an integral role in keeping the public informed.

Read more about The Kokopelli National Theatre.

But more than anything else, the monthly interviews with the county commission and the city council were our greatest service to the community. Imagine every four weeks, being able to hold your elected officials’ feet to the fire. We had our ups and downs, of course, and as I’ve mentioned, for a while county government became a bit aloof for my taste. But most of the time, there was a good rapport between The Zephyr and government when it came to open access, whether we agreed with each other or not.

One of the great joys this paper has brought me was the opportunity to introduce Zephyr readers to the wonderful work of my old friend Herb Ringer. I’d met Herb years before, when I was a ranger at Arches. We became instant friends when he learned I was suffering from a recent divorce; Herb was divorced as well–back in 1939. When his eyes welled with tears and he put his hand on my shoulder and said, “I know how you feel,” all I could think was, ‘Damn…I hope I’M not still grieving decades later.’

One of the great joys this paper has brought me was the opportunity to introduce Zephyr readers to the wonderful work of my old friend Herb Ringer. I’d met Herb years before, when I was a ranger at Arches. We became instant friends when he learned I was suffering from a recent divorce; Herb was divorced as well–back in 1939. When his eyes welled with tears and he put his hand on my shoulder and said, “I know how you feel,” all I could think was, ‘Damn…I hope I’M not still grieving decades later.’

Over the years, he’d visit me at Arches and then in Moab and we became like father and son. Then he started sharing his vast collection of Kodachrome images, thousands of photos taken over the past 50 years, and predominantly of the American West. When I started The Zephyr, it occurred to me I had an opportunity to share these images. For the past 25 years, there has rarely been an issue that didn’t include “Herb Ringer’s American West.”

WHAT ELSE…

People came and went over the years. The writer Robert Fulghum, author of the best-selling book “Everything I Need to Know I Learned in Kindergarten,” befriended The Zephyr for a while. He’d built a home at Pack Creek Ranch in the early 90s and took an interest in our struggling little rag.

At the time, I was still without a computer and when Fulgum heard of our predicament, he immediately provided us with the funds to buy one, and a postscript printer as well. It was a great help and, for a while, Fulghum even signed on as a Zephyr columnist.

Perhaps the most enduring Zephyr writer (besides myself) was the inimitable Ken Davey. Ken came to Moab in the late 80s with his future wife Julie Fox. Ken established himself early-on as an irascible and cranky contributor, but rarely inaccurate. He was also my next day neighbor and we shared what can only be described as one of the most candid friendships I’ve ever known. Ken’s columns not only informed the public and made people think, his acerbic wit diverted attention away from my rants and onto his, giving me a much needed break from whoever it was we’d offended most recently. Ken also wrote for the local weekly and the local television station, “Channel 6.” I can lay claim to the fact that I named Ken the “Dean of the Moab Press Corps.”

In October 1991, I received a manila envelope from somebody named Dan O’Connor, up in Leavenworth, Washington. Somehow Dan had become a regular reader and a subscriber and was troubled by my obvious lack of graphic technical skills. I was, at best, a cut and paste guy with a hot hand waxer. Dan was a graphic computer artist in the finest sense. Enclosed were a selection of new banners for The Z. They were beautiful and his graphic skills would become a regular part of The Zephyr for the next…well..forever. The banner on this issue is a Dan O’riginal.

Washington. Somehow Dan had become a regular reader and a subscriber and was troubled by my obvious lack of graphic technical skills. I was, at best, a cut and paste guy with a hot hand waxer. Dan was a graphic computer artist in the finest sense. Enclosed were a selection of new banners for The Z. They were beautiful and his graphic skills would become a regular part of The Zephyr for the next…well..forever. The banner on this issue is a Dan O’riginal.

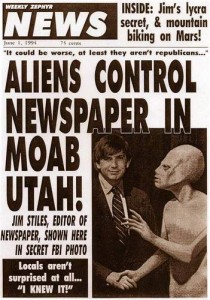

Then, a few years later, another gift from Dan arrived. It was a tabloid style cover for a fictional paper called the ‘Zephyr Weekly World News’ and it announced to the world—“Aliens Control Newspaper in Moab, Utah!” How he knew I’ll never know, but later I put that cover on the regular Zephyr cover. One thing led to another. Dan created his “Twisted Tabloid” series that ran as a regular feature for years and he contributed untold numbers of morphs for our “Lame Alien Swimsuit Issues.” It was such a great relief to sometimes escape the seriousness of the day and lose ourselves in Dan’s great works of art. (And of course the cover of this issue is from Dan as well).

I surprised a lot of my old uranium miner friends when I helped initiate a plan to honor Moab’s most famous citizen, the “Uranium King” himself, Charlie Steen. I’ve written extensively about Steen over the years and his son Mark, wrote an excellent history of his father in The Z years ago, but to remind you, Charlie Steen was a geologist from Texas who came to Utah convinced he could find uranium where it wasn’t supposed to exist. Other geologists and government “experts” thought he was crazy, but Steen persevered. He was down to his last dollar and his last bit when he found the Mother Lode. He became an instant millionaire and a national figure. His fortunes rose and fell, he built a magnificent home on the cliffs north of town, then moved away, lost almost everything.

One evening in early 1992, I was having dinner with Fulghum and his wife Lynn, Robert asked me why all the churches in Moab were in along the same street. I explained that Steen had donated that property to the churches back in the late 50s. A discussion about Steen’s influence on Moab ensued and we both wondered where he was now. Fulghum said,“Wouldn’t it be something to bring Charlie back to Moab?”

And I remembered that his Discovery Day was sometime in July 1952—this summer would mark the 40th anniversary. So I took the idea to City Councilman Dave Sakrison who loved the idea. He took it to the Mayor and Council and they loved it too. Later that year Charlie Steen came back to Moab. A dinner honoring him filled the Elks Lodge; friends came from all over the country to pay tribute. It was a very moving evening for everyone there.

During the dinner, the ‘master of ceremony’ Dave May mentioned the long list of people who had been involved in proposing and planning this event. When Dave mentioned me, every ex-miner in the room turned to me in shock, as if to say, ‘YOU? You treehugger? You want to honor Charlie Steen?’ My old buddy Neldon Lemon, with whom I’d spent many an hour arguing politics and the environment while munching burgers at the old Westerner Grill, came up to me afterwards. “Stiles,” he said laughing. “I don’t think I’ll EVER figure you out.” It was a good night.

The next day, Moab honored Charlie with a parade. Someone had found the original jeep that Charlie had used back in ‘52. Most of the town turned out. Later, we held a huge picnic for Charlie at the City Park and Mayor Tom Stocks proclaimed it ‘Charlie Steen Day.” he also named the recently built park pavilion the “Charlie Steen Pavilion,” but to this day, I don’t know if the city of Moab ever installed a plaque.

But if some of Moab’s miners softened their view of me a bit, there were a few women in town who wanted to kill me.

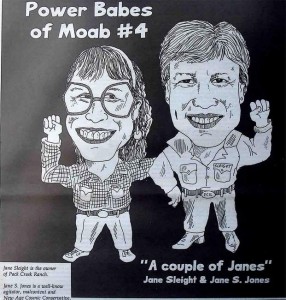

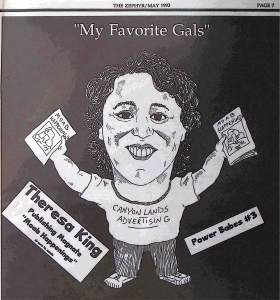

When I started The Zephyr, I had created the ‘cartoon ad’ for almost all of my business supporters. It personalized their advertisements and they were funny and I didn’t charge much. Everything was going swimmingly until I took a shot at drawing a woman. I believe it was Jane Dillon, then employed at Tag-a-Long Tours, who became my first…well… victim. Now keep in mind that I am a CARTOONIST, not a portrait painter. A cartoonist tends to exaggerate features while capturing the essence of the individual. What can I say…Jane had/has a winning smile and when I tooned her she was smiling winningly. The result was a bit more toothy than Reality and way more toothy than she would have preferred. She did not believe I had “captured her essence.” I would pay the price for years to come.

When I started The Zephyr, I had created the ‘cartoon ad’ for almost all of my business supporters. It personalized their advertisements and they were funny and I didn’t charge much. Everything was going swimmingly until I took a shot at drawing a woman. I believe it was Jane Dillon, then employed at Tag-a-Long Tours, who became my first…well… victim. Now keep in mind that I am a CARTOONIST, not a portrait painter. A cartoonist tends to exaggerate features while capturing the essence of the individual. What can I say…Jane had/has a winning smile and when I tooned her she was smiling winningly. The result was a bit more toothy than Reality and way more toothy than she would have preferred. She did not believe I had “captured her essence.” I would pay the price for years to come.

The Moab women were furious. How could I have savaged Jane in this way? What kind of a jerk was I? I tried to explain that it wasn’t my intention to insult anyone. “Think about,” I pleaded. “Advertisers are PAYING me to toon them. Why would I deliberately insult them? It would make no sense.” But it was too  late. Begging for forgiveness was ineffective. I decided that the only thing I could do, to coin a phrase from Annie Oakley, was to “get back on the horse.”

late. Begging for forgiveness was ineffective. I decided that the only thing I could do, to coin a phrase from Annie Oakley, was to “get back on the horse.”

I started drawing Moab’s most celebrated women, featuring them in full page features, but when I got too whimsical and titled the cartoons, “My Favorite Gals,” I got them all stirred up again. So I changed it to “Moab’s Power Babes.” That didn’t help much either.

It would take years for me to overcome the bad reputation I’d unwittingly earned for myself. I stayed away from cartooning and offered renderings instead. Exaggerating facial features was no longer an option. Eventually the Women of Moab forgave me. Note however that all these years later, I have still not cartooned my wife. I have grown wiser in at least one respect.

1995…APPROACHING TERMINAL BURNOUT

In addition to a growing fear of cartooning women, I was starting to show serious signs of burnout. The Zephyr had been, from day one, a one-man show in most respects. I had some great writers and for years, some typing assistance, but otherwise, I did it myself. We printed a paper every four weeks. I’d spend a week walking the streets and talking to advertisers and collecting ad copy, a week gathering stories and conducting interviews, a week writing most of the stories and transcribing interviews, and a week putting it all together (cut and paste style), including those cartoon ads. When we were ready to go to press, I loaded the layout boards into my 1963 Volvo at daybreak and drove to Cortez, Colorado. I was usually back by late afternoon.

In the early days, we only printed 2000 copies and I would spend the rest of the afternoon delivering them to the 25 or 30 businesses where The Z was distributed. The next day, I’d print out the labels on an antique label printer used during the administration of John Quincy Adams and haul the bundles to the post office.

I got to rest for four days and then I’d re-start the process. I did most of this for seven years, though I did get some relief from a few kind souls who took pity and helped out with distribution and the subs. Still I knew I couldn’t keep up this pace forever.

Also, in my heart of hearts, I think I knew that Moab was already committed to a direction and future I wasn’t particularly fond of. It was relatively easy to oppose something monolithically large like a multi-million highway or a toxic incinerator. But how do you slow the insidious growth of tourism? And again, to repeat an old mantra, I didn’t want to stop tourism, I just didn’t want it to dominate the economy. Nor did I want the town to be transformed by out-of-town investors. I didn’t like the idea of a “New Moab.” I liked Moab the way it was–a nice mix of the old and the new. Again, as Bill Hedden had said, Moab was “a hard place to get rich, but a good place to be poor.”

We had a new form of government and a new county council that was supposed to be “progressive,” and it was in most respects. But none of them really wanted to oppose the Slow-Moving Juggernaut of an amenities economy and I wasn’t sure my monthly warnings about the threat made any difference. My friends who had once loathed the changes brought by runaway tourism were beginning to have second thoughts. Unfortunately I wasn’t. But maybe it was time for me to step and back, re-think The Zephyr, and try something different. Enjoying myself and doing something productive and worthwhile was a lot more important to me than making a lot of money.

I began to consider a publication that was broader in scope, that still focused on environmental, political issues of the Colorado Plateau, as well as its history, but could interest a wider readership. To do that I needed to dramatically boost circulation, but it cost money. I knew my advertisers would never tolerate a doubled ad rate, so I proposed a major change—The zephyr would increase its circulation from 2000 to 15,000, but we’d go from a monthly to a bi-monthly schedule. Ad rates would stay affordable and we’d reach a much wider readership, from Moab to Grand Junction to Salt lake City. It would be a gamble to see what happened next.

NEXT TIME: (1996-2001) The Zephyr goes bi-monthly.

Jim Stiles is Founder and Co-Publisher of the Canyon Country Zephyr.

To read the PDF version of this article, click here, here, and here.

To comment on this article, scroll to the bottom of the page.

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!

I have the “aliens control newspaper . . .” issue nailed up in my studio/garage here in NM. I even moved it here with us from CO — against my wife’s wishes to “throw out that old useless rag — or better yet, burn it along with all of the rest of your s#*t.” I’m thinking it “may have been photoshopped” although I’m not sure that tech was available at the time. Maybe it was just cut and pasted like in the old days of “real” journalism. (They may very well be a copy of that issue also down at the Roswell UFO Museum.)