It should shock no one that, when I was in school, I often fought with my professors. I was raised by parents who taught me to trust my internal logic, and so when anyone, even authority figures, told me something that felt “off,” I would protest.

In this way, I was well-suited to the English Department. Most of my professors tolerated my disagreements, tiring as they must have been, and a few of them challenged me in turn—forcing me to examine and flesh out my gut feelings into more articulate arguments.

One such “gut feeling” came upon me early in my literature courses, when professors began to define themselves into the “schools” of literary theory—feminist theory, Marxist theory, Queer theory, etc. If you’ve never been an English Major, then you’ve never faced the question of which “critical” school you should choose. And I tested the patience of my beleaguered teachers through each course with my refusal to accept any of them.

“Why,” I would ask, “should I come to a story with a theory? Shouldn’t the story come first, and then my interpretation after?”

I was told a hundred times that this debate had already raged in academia, and that it had been won conclusively by the theory-holders years before my arrival. The decision had been made, by thousands of people more qualified than I.

And here I should pause to admit that the theory-holders had a point: no reader comes to a story without baggage. Most of the official “readers” throughout history had been wealthy, white men, and they could only pretend they valued the “meaning” of literature above their own personal prejudices because they believed those prejudices were unquestionable truths of the universe. So these wealthy, white readers weren’t surprised when their readings of literature found those same unquestionable truths reflected in every story.

In short, every reader comes to a story with politics, but it’s only feminists, Marxists, and other less powerful voices whose political thoughts are seen as being “outside” the meaning of the story.

It’s a fair argument, but in the end, it dissolves into cynicism. To me, it felt like intellectual atheism–like saying, “There is no real meaning in a book besides what a reader projects onto it, so let’s just go with that.” And I remained Agnostic. Sure, I didn’t have the answers. I could never provide an unbiased reading of a story. But, even if I could never find the inherent meaning of a story, that didn’t prove such an inherent meaning didn’t exist. And it didn’t prove that we should stop striving to find it.

Finally, in my Senior year of college, one professor summarized the “theory” argument in one phrase, recognizable to the point of cliché, written in chalk before our class: “The Personal,” she wrote, “is Political.”

And all my “gut feeling” sensors went DING! DING! DING!

Something here is wrong.

This is the point at which my academic debate veers suddenly into the public square.

Firstly, I should acknowledge that the phrase “The Personal is Political” has been used in a number of contexts since its origins in the Second Wave Feminism of the 60s and 70s. Originally, I believe it was an argument that the personal, or domestic, struggles of womanhood were symptomatic of the larger power imbalance between the sexes. I can’t argue with that. But, forty years after Second-Wave feminism, I’ve also heard that phrase used in reference to animal rights, labor issues, environmentalism, and Fair Trade issues.

It’s a handy phrase, because, on its face, it is undeniably true. Every act, every purchase, takes place within the larger context of society. Your choice of milk, of clothing, your job, what your trash looks like, is all reflective of, and contributes to, a larger society.

So what’s the problem?

Look with me through a window at a family scene—a child’s birthday, the mother turning off the lights, the father alighting the candles on the cake. The child struggles to remain still in his chair, as he  silently practices his wish. How would you describe this scene? What is important? The emotions of each person? The inexpressible magic of youth? The bittersweet passage of time? Or should we focus on the ingredients of the birthday cake—the Fair Trade practices of their countries of origin, the treatment of the animals involved, and the labor conditions under which each ingredient made its way to this particular kitchen? How about the manufacturing of the family’s clothing, their furniture, the energy efficiency of their various lightbulbs?

silently practices his wish. How would you describe this scene? What is important? The emotions of each person? The inexpressible magic of youth? The bittersweet passage of time? Or should we focus on the ingredients of the birthday cake—the Fair Trade practices of their countries of origin, the treatment of the animals involved, and the labor conditions under which each ingredient made its way to this particular kitchen? How about the manufacturing of the family’s clothing, their furniture, the energy efficiency of their various lightbulbs?

Would you reduce it to the work-home balance of the two parents—whether their salaries have risen with inflation, or the availability of affordable daycare for the child?

Undeniably, all this minutiae is a part of the scene, and contributes in a way to our understanding.

But, if you asked your child whether he enjoyed his birthday, and he replied by praising the Fair Trade Cake Flour, wouldn’t you be disappointed?

I should explain that I am mainly having this debate with myself. I spend a great deal of my time focused on political matters—the rise of the surveillance state, the destruction of the laboring classes, environmentalism, feminism, etc. I worry over our grocery purchases, over antibiotics in meat, and pesticides in produce, and the rise of factory farming. I spend hours every week reading news articles and analysis, confirming or questioning my political positions until I feel some measure of comfort in understanding, at least, the terms of each political debate.

But then Spring comes. And, when I’m out in the garden, or I’m watching our cats tussle with each other in the grass, or I’m on an evening walk with my husband, I think, “This is what life is about. Not that other crap.” It’s so satisfying to spend my days working with Jim on projects around the house—to relax in the evening with dirt under our fingernails and some ache in our muscles. On those days, the thought of sitting down and typing out an article seems positively wasteful. All that time spent wrestling mentally with policies and unfair practices gives me no pleasure compared to an afternoon wrestling with the rose bushes.

But then Spring comes. And, when I’m out in the garden, or I’m watching our cats tussle with each other in the grass, or I’m on an evening walk with my husband, I think, “This is what life is about. Not that other crap.” It’s so satisfying to spend my days working with Jim on projects around the house—to relax in the evening with dirt under our fingernails and some ache in our muscles. On those days, the thought of sitting down and typing out an article seems positively wasteful. All that time spent wrestling mentally with policies and unfair practices gives me no pleasure compared to an afternoon wrestling with the rose bushes.

Politics, by nature, are extrinsic. They are outside the self. Under any definition, “Political” activities have to do with public acts, the organization of large groups of people. And what troubles me most about lumping in the “political” with the “personal” is the tendency to stress the former at the expense of the latter.

To explain what I mean, we’ll have to go back to adolescence.

Psychologically, being a teenager is all about “identity.” A teen is the clumsiest creature in existence because she can only express her “self” via pantomime. I will never forget the look on my father’s face the day I appeared before him, 13 years old, dressed for a trip to the grocery store in knee-high combat boots and about three inches of caked-on makeup.

“You know,” he said dryly, “No one else will be in costume.”

It’s a ridiculous stage of life, and I am overcome with pity for every kid struggling thought it. It’s only when you’re older that you understand the importance of that time, to teach you that you can’t “put on” your identity. You have to grow yourself from inside, and let your choices reflect who you’ve become.

Culturally, I think that’s a lesson we’ve forgotten.

All the attention, these days, is on a person’s choices. Do you buy local? Organic? Do you know the difference between an “all-natural” and an “organic” label? Are you using cloth diapers? Did you eat at the new, locally sourced, organic restaurant?

We accrue our identity through our stuff. To become a “free spirit” you need to have that particular Moroccan-style rug, and this set of Kantha pillowcases. To be an environmentalist, suit up in North Face and Patagonia. It takes the work out of being yourself, doesn’t it, when you can order up a full-blown personality from a catalog?

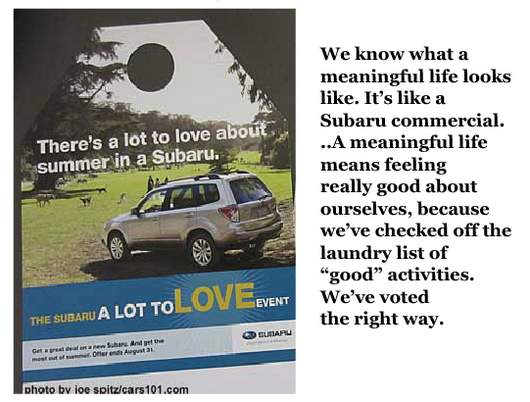

We know what a meaningful life looks like. It’s like a Subaru commercial. Or that Eat, Pray, Love book. Or a music video. A meaningful life means feeling really good about ourselves, because we’ve checked off the laundry list of “good” activities. We’ve voted the right way. We bought the right laundry detergent. We’d just like to give the world a Coke. In short, we’re wearing “goodness,” but we’ve never been asked,“What defines the Good?” “Where does your morality come from, and how do you justify your actions?”

There is a good reason why most people roll their eyes at hipsters. Yes, backyard chicken coops are a good thing. Yes, buying local and collecting vinyl are good things. It isn’t the trappings of hipsterdom that bother everyone. It’s the way those trappings are fabricated into an “identity.” You can have tattoos, or work at a sustainable coffeeshop, or bike everywhere without being a hipster. Hipsterdom comes from wearing those choices like a uniform.

What drives me crazy is seeing how, so often, the political “creates” the personal. We’ve forgotten that the “personal” self exists, on its own, as an individual life exists, and that the politics come second–either enabling the personal to flourish or else standing its way. The personal and political are  entertwined, but they are not the same thing. You are not what you [fill in the blank.] Yes, you are judged, and judge yourself, for your actions. But your actions are not you. In the same way that a raspberry is not the same as a raspberry bush. First, you cultivate. Then come the fruits.

entertwined, but they are not the same thing. You are not what you [fill in the blank.] Yes, you are judged, and judge yourself, for your actions. But your actions are not you. In the same way that a raspberry is not the same as a raspberry bush. First, you cultivate. Then come the fruits.

If you’re doing it right, then what you buy, how you vote, how you speak, are reflections of who you are. But we shouldn’t confuse the reflection for the reality.

First you develop a self. And then you hope your actions will reflect what is there.

There was a time before the consumerist frenzy—before companies figured out how to confuse a person’s desire for freedom with their desire for designer jeans. And, in that time, I think people needed to be reminded that, yes, their personal acts were also political. But now we lean toward valuing our activities as political first, and only “personal” in the fact that we carry them out as a person. So much time is spent doing what looks good, and repeating what sounds good, and so little time is spent developing “goodness” in ourselves. It’s simpler to pantomime the actions we see reflected around us—to value the identity granted to us by our lifestyle—but ultimately those values ring hollow.

Maybe here, too, I rely on an agnostic faith in the soul. Maybe we can’t each find the inherent meaning in our lives. Maybe we’ll always have to rely on the crutch of society to tell us what’s important about ourselves. But we should be careful in following that thinking to its cynical end. Otherwise, after a lifetime of posturing and costuming, we may find the undervalued self within us had long ago slipped away.

Tonya Stiles is Co-Publisher of the Canyon Country Zephyr.

To read the PDF version of this article, click here.

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

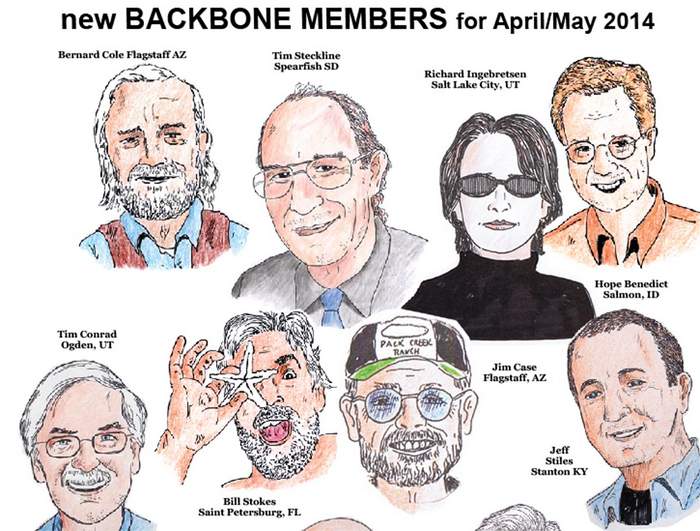

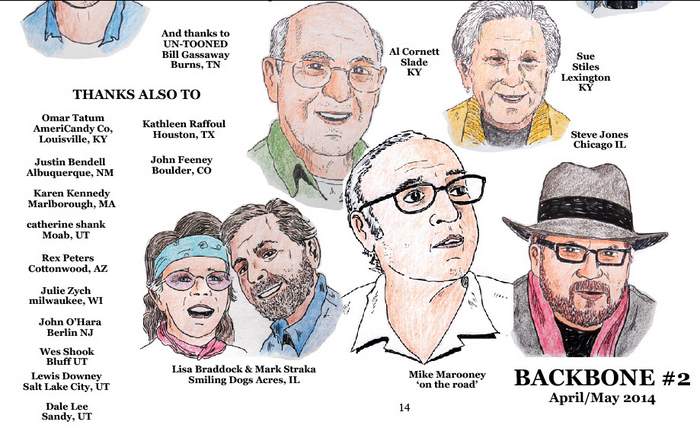

Don’t Forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!

As always enjoyable but perhaps more thought provoking than other times. This issue really effects all of us more every day. I think this is at the root of the social and political.”camps” that are so clear and prominent today. Years ago a young lady related to a woman I was dating brought up politics at a holiday dinner. It became clear to me that she was not well read but had sunk her teeth into a popular radio show and now considered herself an expert on politics, social issues and foreign policy. She could not come close to an original thought but she could recite quotes from the radio. She had stunted her own mental growth in my opinion. I recommended she read a book now and then. She asked for a recommendation. I told her to start with any book and keep reading. She thought I was an old fool. Sad and lazy.

Tonya, the sound of enlightenment continues to ring from your columns. Always a pleasure, thanks!

Saying that the personal is always political is the same as saying that the personal is always ideological.

No it isn’t!

Thanks for deconstructing this simplism..