Recently, the Utah Wildlife Board proposed a hunting season for crows. While they are not particularly tasty and are known for their intelligence, crows have often been blamed by farmers for agricultural losses via crop damage—crows have to eat, after all—and so, next September, crows may be fair game for anyone itchy to shoot something.

Critics argue that the crows do not constitute a significant threat to agriculture and, in Utah, are not as prolific as they are back east. And some are concerned that most people can’t differentiate between crows and their larger cousins, the raven. It worries me too.

While a shooting season on crows seems misguided and wrong, I particularly resent the possible assault on ravens. The truth is, ravens get no respect. Wherever they fly, they’re ignored or misidentified. Everyone wants to see an eagle. Nobody cares if they see a raven. It’s always been like this…

One warm summer night, many years ago, I was a seasonal ranger at Arches National Park, collecting fees at the Devils Garden campground. We went site to site in those days, actually talking to the campers, and while it was a thankless job in some ways, (“We already paid at the gate…You mean we have to pay again?), there were some advantages to this kind of direct contact. On this particular evening, a woman from L.A. was about to invite me back for a Hibachi dinner, when I was called away by the gentleman in an adjoining site.

“Oh ranger,” I heard him call. “You’ve got to see this.” A pair of 7X50 binoculars bounced rhythmically off an ample abdomen as the camper from site 29 lumbered toward me.

“What seems to be the problem?” I asked. I always assumed there was a problem when tourists ran at me.

“No problem,” he explained. “But I think I just saw an eagle flying over there by that big arch.”

“No kidding,” I said. “Can you still see it?”

“Well, actually the wife spotted it first…Mother! Can you point out that eagle to the ranger?”

She left her dishes and joined us by the road. “Let me see…give me the binoculars, Gil…Yes! There it is!”

High above Skyline Arch I could see the dark soaring outline of the winged figure. It was a magnificent bird alright, but it wasn’t an eagle.

“

That’s not an eagle, ma’m,” I said. “That’s a raven.”

“What? Give me those field glasses, Mother.” Gil was not convinced, but the binoculars gave him a sharper and closer view.

“Damn, mother…it’s just a big crow.”

“Now just a minute,” I said indignantly. “It’s not just a crow, and it’s not just a raven. It is one of the most intelligent, graceful, and fascinating birds you will ever hope to see. If I could come back to this life as any creature on Earth, I would return as a raven.”

Gil and Mother failed to be moved by my passionate defense of the raven. “That’s fine ranger…real interesting…Honey, do you need any help with the dishes?”

Sometimes spontaneous interpretive talks are an effective way to educate the public about the wonders of nature. This was not one of those times. I was left by myself, on the top of this sandstone fin by the campground road to contemplate the solitary raven.

I wasn’t always a staunch defender of the Black Wonder. As a kid in Kentucky, my knowledge of ravens was limited to Edgar Alan Poe, and my grandfather regularly shot his BB gun at the cousin crows that inhabited our neck of the woods (The raven, in this country, is mostly confined to the Western U.S., although they’re widely distributed, from Africa and Eurasia, to Australia and Central America.).

But on a trip, many years ago, to a remote section of the Grand Canyon, where the rim plunges more than 2000 feet to the Colorado River, I had my first opportunity to watch the remarkable acrobatic skills of the “Common” Raven. I’d never seen anything like it in my life.

Sometimes in groups of three or four, sometimes in pairs, sometimes alone, the incredible Corvus corax performed flying feats that I thought defied the laws of nature. In groups they engaged in furious dogfights and mutual pursuits. They plummeted into the canyon, their wings tucked in to reduce drag, and as they free-fell, they spiraled and spun in perfect harmony with the other. When they caught an updraft, they would reduce direction in a great swooping rush and ride the wind as high as they could go. When they sensed the apex of their ascent, the ravens arched over on their backs, and started the process all over again.

They kept this up for hours, flying and performing, it seemed, for the sheer joy of it. I never forgot the show and, later as a park ranger, I felt it was my job, my duty, to speak in their defense. There is much to say in their defense too. As omnivores, ravens depend upon a wide variety of animal food, supplemented by some plants. They are also scavengers, taking advantage of carrion when it’s available (and keeping our highways clean, I might add).

Ravens are believed to mate for life, which is more than a lot of us can say, and some raven watchers report that both parents incubate the eggs (the males must be the apple of raven feminists everywhere). Ravens will fiercely defend their nest against intruders, whether they be raptors or humans. I once read of an incident in Oregon where some nosy ornithologists attempted to examine an active nest. Both parents left the nest when the group approached the nest. But as they were climbing down, the ravens returned. One of the ravens picked up rocks in its beak and hurled them down at the fleeing birdwatchers/annoyers.

But to me, more than anything, these birds seem to have an extraordinarily refined sense of humor. Years ago, ravens built a nest on the cliffs above the Arches visitor center. When the young birds fledged the nest, they made a bee line for the front yard of the old rock house, then headquarters of the Canyonlands Natural History Association. All three fledglings and the parents congregated on the grassy lawn and awked and squawked and croaked the mornings away, much to the chagrin of the director of CNHA, Eleanor Inskip. Eleanor was unable to concentrate with all that noise and, on several occasions, ran out the door and attempted to chase them away. But the ravens always came back and after two or three days of being harassed by Ms. Inskip, the ravens shit all over her car. There must have been five or six cars to choose from, but they picked hers. Realizing she’d been outwitted, she gave up and bought ear plugs.

And in 1983, when that despicable Secretary of the Interior, James Watt came to visit the park, all the dirty tricks that Earth Firsters! and other ne’er-do-wells concocted, could not compare to the almost perfect aim of one raven named George.

George was a shameless beggar who spent his days bumming food off tourists and whatever the park maintenance man, Rocky Newell, cared to give him. I used to tell Rocky not to feed all that Wonder bread to George, but Rocky just laughed. “James, my boy, George doesn’t take ‘no’ for an answer,” he explained. “It’s better to stay on George’s good side.”

I don’t know what Watt did to violate that piece of advice, or perhaps George was just a natural judge of character, but as the Secretary walked across the Windows parking lot to his car after an exhausting 100 yard hike, Jim found himself a slowly moving target. With a great flapping of wings, George took to the air, ignoring an apple core and a piece of baloney, and headed straight for the chrome-domed Man. At the appropriate moment, he released a white incendiary bomb, and almost hit his mark. It was a monumental effort by the Great Black Bird, and what really matters is that he tried. Watt left the park shortly thereafter, never returned to Arches, and a year later, resigned (some say in disgrace) as Interior secretary. I firmly believe that George’s symbolic attack was the catalyst the country needed, the statement that had to be made, to confront James Watt, once and for all.

Today, as on any day, I can find great pleasure and joy in watching the ravens. Whether they are performing aerial stunts, and going for maximum aerodynamic efficiency, or lazily flapping from one fin to the next, with their legs dangling freely beneath them, the fact that they are ignored and underrated by most bird watchers may bother me, but it doesn’t bother them…they could care less.

They’re too cool to care. Or be shot.

For more information on the proposed crow shoot:

http://www.sltrib.com/sltrib/

BONUS FEATURE:

If you doubt the intelligence of the raven…or crow…check out this YouTube video: “Tool Use in the New Caledonian Crow”

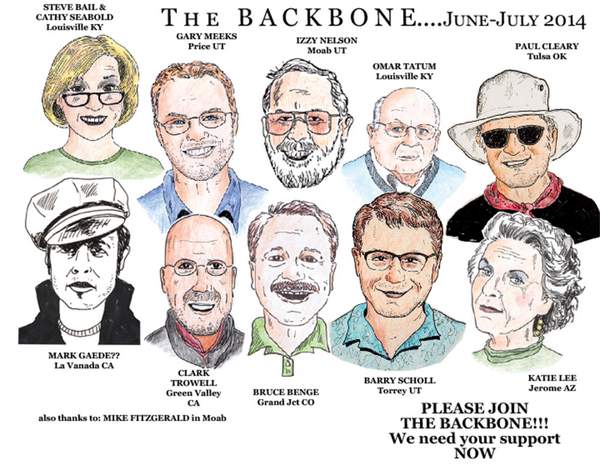

Jim Stiles is Founder and Co-Publisher of the Canyon Country Zephyr.

To read the PDF version of this article, click here.

To leave a comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!

The Corvid family thanks you, Jim. Great defense!

A fun read. Loved the bird bombing of James Watt. What a target. So much head, so little…..

Living in the east, Kentucky I can not verify I’ve ever seen a raven. Hope to one day. I sure get the crows here and I don’t have a beef with them. Some seasons they take over the property and surrounding woods and they provide entertainment for me. All of the variety of birds do in their own ways. Actually watched an ospry catch a fish from a neighbors pond and bring it to a tree top on my place to eat it. Move over national geographic that was GREAT! Another time I watched a skunk and a large Buck solving a land dispute. That was fun too but I digress. Birds, including ravens bring us something distinct in their own nature. I love what they do for me and others that appreciate them.

I watched a half dozen of these incredible animals playing in the cliffs near the river just above Cisco about fifteen years ago. Last year, I watched maybe a dozen playing on the currents among the cliffs in Bang’s Canyon near Grand Junction.

No reasonable human could fail to see the analogy between their play and our play. Both days were warm and sunny. In both cases, they played among rock formations that would direct the wind currents, facilitating their speed and moves. The number of repetitions of highly skilled flying maneuvers and their side by side and follow-the-leader moves had no apparent purpose for mating or finding food. They seemed to be completely delighted with their mastery of currents and flight and with sharing it with buddies.

About five years ago, I watched a raven harass a great horned owl in a cottonwood across from my house. A raven is no match in size or weapons for a great horned owl. The raven was well aware of that. Based on what I observed, however, the raven may be better and faster in flight and wit.

The raven would move carefully toward the owl. The owl simply remained perched in place during the raven’s approach. When the raven came close, the owl would try to hit the raven with his beak. The raven would quickly retreat with a quick flight to a nearby branch. He would then begin the approach again. Over and over again, this episode lasted for a about twenty minutes before the raven flew away. The owl remained in the tree for about another fifteen minutes.

I don’t know the story, of course, but I would say the owl, rare for that area, had flown into the raven’s nesting or hunting area. The raven was letting the owl know that this was not something he or she was going to allow without a fight.

That a creature this smart would shit on Watt is no surprise to me. Thanks, Jim.

A Raven Moment

Several years ago, while hiking along the Murphy Trail in Island in the Sky I stopped to eat lunch and sat down at the edge of the cliff. As I was eating, a raven landed on the edge of the cliff about 100 feet away. When it made a call (to get my attention?) I imitated the sound (to impress myself?), and we wound up calling back and forth for a minute or two, with me always cleverly and ineptly trying to replicate the raven’s varying calls. I resisted the urge to throw any food toward the raven and after another minute or two it flew off.

The next thing I knew the raven was flying in the void in front of me, directly at me, at my eye level. It settled into a glide, directly toward me, looking me straight in the eye, and without taking its eye off me did a perfect 180 degree roll and flew upside down for a second or two. While upside down, without taking its eye off me, it gave out a loud CRONK (or some such raven word), immediately rolled back upright, flew off and was gone.

Whatever it was the raven said in that inverted moment, I felt as if I had been put in my place, either for presuming to imitate its calls or for not sharing my lunch.

I will always feel honored to have been given the finger by a raven.

ah, raven! Once in a box canyon near I-70’s entrance to the Swell, I used my baroque recorder to tease out a novel’s worth of different calls from a family of ravens. According to researchers, ravens have over 100 different vocalizations. I can believe it! Just a few weeks ago, I watched a raven bugging a bald eagle. The eagle was cool, I’ll give him that, but the raven seemed to be saying, ‘what are you doing here, ya big putz? This is >my< neighborhood!" Excellent bird show, as always.

Thank you for your fab defense of the trickster in the sky. I recently learned a group of Ravens is called an “Unkindness” of Ravens… I prefer to think of a “Laughter” of Ravens…. My husband makes a Mead he calls “Giggling Raven Mead”. Alas, the fine protective alcohol laws make it prohibitively cumbersome to sell the stuff… (Nice to know we’re safe)… Thanks again…

Wonderful story!

After all, it ain’t whether you’re a smart-ass, it’s whether you use it to good effect. Ravens are boss in this department.

The ravens that live about the parks out west are particularly savvy to human behavior and psychology. They will indeed confront one in the backcountry, sometimes for extended encounters. Conversations I’ve had with ravens of Utah come to mind. . . . But I want to give tribute to a raven that has lived in Chesler Park area for many years. It will hang out and charm a camper, waiting for a back to turn, and then two flaps and the real target is revealed. Once the raven at Chesler stole a small scented candle and took it up to a needle to gloat over and cackle about for the next day. A couple years later I was at a campsite in Elephant Canyon when the same fella visited. I turned my back five steps from my pack, and he made a beeline for the top pocket, under which he disappeared just long enough to extract a goodly hunk of cheese, then flew flapping and laughing across the canyon to roost on a ledge and enjoy his repast at his leisure. When I mentioned him to rangers, they knew the rascal right off. I hope he or she is still out there shilling the campers. God bless Raven and the spirit of Raven. Thanks Jim.

I was a seasonal ranger at Indian Gardens campground in the Grand Canyon in the 1980’s. There was a resident pair of ravens there named Raoul and Ramona. They made their living stealing food from the tourists. Many a time I observed someone leave a sandwich on a picnic table and make the mistake of turning away momentarily. The entire sandwich would fly away in a blur of iridescent black wings. It would then be consumed in an adjacent tree in plain site of the theft victim. Raoul and Ramona’s favorite time of day was when a group of a dozen or so mule riders stopped to eat their Fred Harvey prepared box lunches on benches in the campground. Fruit, granola bars, sandwiches etc were gleefully pilfered. Raoul would taunt the tourists from a tree limb while shredding their lunches. Ramona would be delivering food to her brood of the year. As the fledglings matured, the parent birds meticulously passed on their skills.

Like you, Jim, I marveled at their aerial shows in the Canyon. And I really appreciated their utter disdain of us humans and their total superiority to just about all other species on the planet. Sometimes a pissed-off tourist would report a raven food theft at my ranger station. I had to explain that ravens are totally exempt from NPS regulations and all the other “legislated” laws. The ravens were just teaching the laws of survival to the uneducated humans.

Dave Stimson

In 2011, I brought part of my New Jersey family to Yellowstone National Park for a week to see its vistas, geyser basins, and wildlife. At one of the trailheads, an obviously brazen and well-fed raven gave me the once over, flew in my direction, and landed no more than 5 feet from me perching on a fence. It was all too obvious he/she was looking for a treat. Now as a trained wildlife professional, my guiding principle is never to feed wildlife. Yeah well…we had a blast feeding it dehydrated banana chips. He ate all we gave him until finally satiated, he flew away to lure in the next unsuspecting tourists. I think ravens are phenomenal creatures.

In Rockville, where I grew up in the 50’s no one ever shot a raven. Even though every bird (except a robin) was fair game at any time, ravens were never in range of a .22 or even a high power rifle. If while two or three of us were hunting together we saw a flock of ravens, someone would always say, You can’t shot a crow (we called them crows), they’re too smart to get close enough to shoot. Someone else would mention that it was guns, not people; they stay a lot closer if you didn’t have a gun. This was said with respect and a little wonder. I don’t know what became of the proposal for a crow hunt, but I think after a season or two, the ravens will be safe.

I regularly give the ravens offerings at my mountain home in the West. Not enough for them to rely upon, nothing to make them sick… just appreciation. I leave the offerings upon a boulder 25′ in front of the door.

One morning I awoke to find three ears of indian corn, with leaves, upon the boulder. It was a stolen holiday display. I could not believe my eyes. I thought myself imagining it, as if having a vision. I went out to touch the corn. It was real all right.

I believed it to be a return of kindness to me. I took the spirit of the offering, but left the corn for the ravens to feed upon.

They very much know who I am and are fascinated by me. I think they like me as much as I like them, to the point where they are playful with me. ((Anthropomorphizing heavily here, now…))

One day passing by my telephone pole, I saw a rock drop at my feet and bounce. I looked up and saw a raven perched, as if laughing. I smiled up and said “hey!”

The ravens are my friends. I feel safe under their gaze…

…

Please don’t shoot the ravens (nor any birds). They are sacred. How often does one get to commune with a wild animal? I have rarely felt closer to nature… Though some of my encounters with ducks, road runners and quail sure make me feel the grace of nature and God’s love as well…

Great article. And I DO care if I see a Raven. One of natures most spectacular creatures. Unfortunately, all the critics and science on the planet didn’t help our battle with the wildlife board in Utah. It’s funny that all the meetings and fight that the state position caused, resulted in 1 permit being purchased for last years ‘crow hunt’. Idiots being bought by SFW and other idiots wanting something to shoot at during “off season”, the REAL reason the ‘hunt’ was initiated in the first place!

Ravens are wonders of the air, and I’m all for crows too. I’m not revealing any secrets by announcing that Utah politicians are nuts.