“I tossed my empty out the window and popped the top from another can of Schlitz. Littering the public highway? Of course I litter the public highway. Every chance I get. After all, it’s not the beer cans that are ugly; it’s the highway that is ugly.” – Edward Abbey

Was this simply a gesture of contempt by a smug writer for the rules of society that ordinary people have to follow? In short, was he just acting like an asshole? That’s more or less how one eyewitness took it in this account by Ed’s old buddy Jack Loeffler:

Was this simply a gesture of contempt by a smug writer for the rules of society that ordinary people have to follow? In short, was he just acting like an asshole? That’s more or less how one eyewitness took it in this account by Ed’s old buddy Jack Loeffler:

“We drove through the late afternoon light northward until we finally reached Green River. Ed and I drank beer all the way. Every time Ed finished a beer, he tossed the empty bottle out the window of the car, spewing glass in his wake. I had grown used to this behavior over the years, but Kath [Loeffler’s wife] couldn’t stand it…

…

[With Loeffler driving…]

“‘Quit throwing your bottles out,’ said Kath.

“‘Nope. I can throw beer bottles out whenever I want to,’ said Ed.

“‘Behind every great man is an asshole,’ said Kath.

“That got to Ed and me and we both started to laugh uncontrollably, Renee’s car weaving through the night on a course of its own.” (Adventures with Ed, 2002, pp. 234-235.)

This was an understandable reaction on her part. Trouble is, as an explanation it doesn’t quite fit. Because whatever Ed Abbey was he wasn’t petty, nor was he given to cheap efforts at self-promotion.

Well, what about alcohol abuse? Does that explain anything here? That Ed drank heavily at times doesn’t by itself tell us much. The relevant question is whether he became an alcoholic. And as a professional alcohol and drug counselor I think the evidence in his case is ambiguous (and that in itself is unusual).

The reason this question matters is that practicing addicts lose that sensitive touch which makes emotional intimacy possible. As a result the addict persistently acts in a mean-spirited way that seriously damages close relationships. Recent brain imaging research confirms the importance of this point: the pre-frontal cortex, the part of the brain that processes both verbal and non-verbal relationship cues, is at least somewhat impaired in unrecovered addicts.

The reason this question matters is that practicing addicts lose that sensitive touch which makes emotional intimacy possible. As a result the addict persistently acts in a mean-spirited way that seriously damages close relationships. Recent brain imaging research confirms the importance of this point: the pre-frontal cortex, the part of the brain that processes both verbal and non-verbal relationship cues, is at least somewhat impaired in unrecovered addicts.

But strangely, even though Ed was clearly tolerant to alcohol, I don’t see serviceable evidence that he ever lost that touch. In fact, throughout his adult life he maintained close relationships with friends who shared his most serious professional and personal interests. Jack Loeffler would not have written a fine, 290 page biography of Ed if Ed had merely been a co-swallower. They had a much richer connection than that.

More significant still, Ed maintained a continuing relationship of the greatest emotional and spiritual intimacy with the wild landscapes of the American West from the first time he laid eyes on them as a young man. I have never encountered such a phenomenon in a practicing addict.

So no, I don’t think Ed threw beer containers on the highway merely because he was obnoxious or because of his drinking. He was too much in touch with people for that.

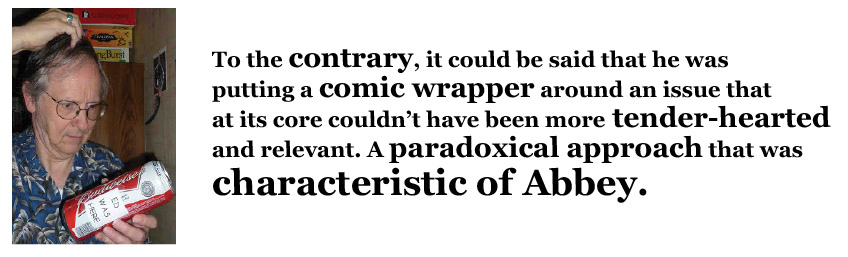

To the contrary, it could be said that he was putting a comic wrapper around an issue that at its core couldn’t have been more tender-hearted and relevant. A paradoxical approach that was characteristic of him.

First, the comic wrapper. Ed’s crack about the beer cans and the ugliness of the highway, reinforced by his inveterate beer tossing, served as an ongoing punch line. It had the classical elements of shock and absurdity, applied with a deft touch. Ed knew as well as anyone that comedy is a subtle art that can hit like a sledgehammer.

Second, what’s inside the wrapper. Ed wanted his readers to understand that even a single paved road can be as much a means of destruction as a revolver or a rocket launcher or an AK-47, and he knew this from first-hand experience. And he was more than willing to offend readers who refused to widen their vision enough to see this.

Here is how he got that first-hand experience. In the late 1950s he was working as a seasonal ranger at Arches National Monument in Utah. At that time it was an isolated outpost, accessible only by a washboard dirt road. While sitting in the secluded desert splendor outside his trailer one afternoon near sundown, “It was then that I heard the discordant note, the snarling whine of a jeep in low range and four-wheel drive…

“…the jeep turned in at my driveway and came right up to the door of the trailer. It was a gray jeep with a U.S. Government decal on the side – Bureau of Public Roads…Inside were three sunburned men…and a pile of equipment…

“…I got the full and terrible story, confirming the worst of my fears. They were a survey crew, laying out a new road into Arches.

“…the new road – to be paved, of course – would cost somewhere between half a million and one million dollars…

“…Don’t worry, they said, this road will be built…when this road is built you’ll get ten, twenty, thirty times as many tourists in here as you get now…

“As I type these words several years after the little episode of the gray jeep and the thirsty engineers, all that was foretold has come to pass…you will now find serpentine streams of baroque automobiles pouring in and out…in numbers that would have seemed fantastic when I worked there: from 3,000 to 30,000 to 300,000 per year, the ‘visitation,’ as they call it, mounts ever upward.” (Desert Solitaire, 1968, pp. 43-44.)

Indeed, in 2012 the visitation at Arches topped 1,000,000.

Let me take this principle from my work as a counselor: when a person repeatedly says and does something with great depth of feeling that on the face of it seems irrational, there’s a good chance that something horrible has happened either to him or to someone he loves. In Ed’s case that someone was the delicate wildness and spiritual solitude of Western lands in which he had immersed himself and which he deeply loved. They were as alive to him as any woman, man, or child with a measurable heartbeat, and they were just as vulnerable to abuse and exploitation.

Indeed, the destruction of the wildness of Arches National Monument (now Arches National Park) by unrelieved vehicular congestion – via that single paved road – was a process that was inexorably repeated on wild lands throughout his beloved West. It decimated one sublime horizon after another. Like the slaughter of the Buffalo in the 19th century, this plethora of paved roads in previously remote places was annihilating what was precious to him.

A defining characteristic of fiercely determined activists, the ones who refuse to be intimidated by people in power, is having suffered a hideous personal loss or degradation. Segregation in the American South was ended by African-American street protesters who were willing to die rather than endure it any longer. And motor vehicle deaths have been substantially reduced by Mothers Against Drunk Driving (MADD), an organization of mothers whose children were killed by drunk drivers.

When it came to protecting his beloved wild lands from degradation, Ed Abbey was an activist of this kind. The real deal. And something extra.

You can see this in the Introduction to his 1977 book The Journey Home, wherein he employed his comic manner to explain that he was not a “naturalist” writer, as establishment critics had ignorantly assumed: “…the only birds I can recognize without hesitation are the turkey vulture, the fried chicken, and the rosy-bottomed skinny-dipper…I’ll never make it as a naturalist. If a label is required say that I am one who loves unfenced country.” (p. xiii.) And then came his central point: “My home is the American West. All of it…,” adding that his book was “in its emphasis an effort to defend that home against alien invaders – as will be shown – from another world.” (pp. xiii-xiv.)

You can see this in the Introduction to his 1977 book The Journey Home, wherein he employed his comic manner to explain that he was not a “naturalist” writer, as establishment critics had ignorantly assumed: “…the only birds I can recognize without hesitation are the turkey vulture, the fried chicken, and the rosy-bottomed skinny-dipper…I’ll never make it as a naturalist. If a label is required say that I am one who loves unfenced country.” (p. xiii.) And then came his central point: “My home is the American West. All of it…,” adding that his book was “in its emphasis an effort to defend that home against alien invaders – as will be shown – from another world.” (pp. xiii-xiv.)

A more subdued and less comedic way to say this is that just because in the early 20th century we Americans learned how to pave roads for automobiles doesn’t mean we knew how to use those roads. Or that we know now.

That “something extra” was Ed’s intuitive vision, and in that he had few peers. Consider the following from his story “The Second Rape of the West” in The Journey Home, the first paragraph of which featured Ed’s quote on tossin’ beer cans. Bear in mind that he wrote these words almost forty years ago:

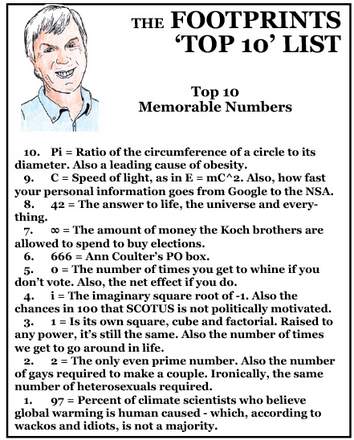

“An immediate and required step forward is stabilization of the energy growth rate. This will be forced upon us sooner than expected in any case.” (p.184.) As far as I can tell Ed didn’t know anything about climate change, but he sure was right about the energy growth rate slamming into a wall called reality. The irony is that we wouldn’t be in the climate crisis or in it nearly as deep if our leaders back then had had the wisdom to take what Ed said to heart. We’d probably still be phasing out fossil fuels, but the required pace would be much reduced and our economic system would not be in the mortal danger it is in now.

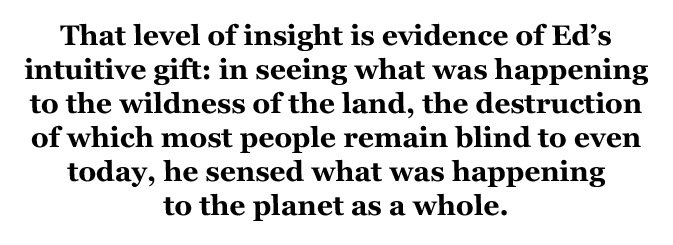

That level of insight is evidence of Ed’s intuitive gift: in seeing what was happening to the wildness of the land, the destruction of which most people remain blind to even today, he sensed what was happening to the planet as a whole. The intuitive function, if it’s strong, goes far beyond what the conscious mind is aware of.

The next quote is from the same story: “If we are driven to manufacture synthetic fuels from coal or to squeeze oil from shale rock – a silly proposition on the face of it – we shall find ourselves expending as much energy as we gain; the net profit becomes marginal. This is the reason the power companies and oil corporations are demanding subsidies from the government.” (p.184.) While in Ed’s day tar sands weren’t being touted by the energy industry, his insight applies equally well to them and especially to the fiasco of the proposed Keystone XL pipeline. Note that in recent years the climate scientist James Hansen has repeatedly said that (1) it is the government’s ongoing fossil fuel subsidies that continue to mislead the public into believing that such fuels are inexpensive, and (2) utilizing unconventional fossil fuels has proved to be not only a silly proposition but the pathway of choice to a climate hell.

My last quote is also from that story: “It is time to begin phasing out the auto industry…Put those men to work making things we need: passenger trains; small, lightweight, efficient buses; bicycles that will last a lifetime….” (p. 186.) Again, just imagine the reduction in CO2 emissions over the last few decades if our leaders had listened to Ed. Instead of the gigantic increases in those emissions that our children and grandchildren will have to cope with.

Two points in closing. First of all, I don’t want to portray Ed as some kind of seer. I disagree with a number of things he said, sometimes strongly. Also, the guy was an enigma and construing what he wrote often involves more than a little guesswork. Sometimes you end up scratching your head.

And a word for Kath: even though watching Ed throw beer bottles out the window was annoying for you, in truth he was hitting a bulls-eye.

Note: I am in no way advocating illegal littering or driving under the influence of mood-altering substances. I am all for lawful behavior and utilizing the First Amendment.

SCOTT THOMPSON is a regular contributor to the Zephyr.

He lives in Beckley, WV.

To read the PDF version of this article, click here.

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!

Great article.

Abbey understood the power of symbolism. When I first started reading Abbey, I saw his beer can tossing and stake pulling as juvenile and fruitless. But then I realized that it sometimes takes such antics to make a statement. The power, of course, came not from the act itself but in Ed writing about it.

I grew up in the East where reservoirs are common. So, when I first fell in love with the desert southwest, I thought that a water-filled canyon was a beautiful thing. It took me a while to realize how wrong I was. The epiphany was not spontaneous. I slowly came to realize that there were people who vehemently opposed the dams and I started listening to them. They got my attention through acts of outrageous symbolism…and they changed my attitude.

when I was a kid in southwest Colorado, and into my 20’s, I habitually littered. My thought process was manifold, contempt& defiance for rules, but also for the endless tourists, and the wealthy among them who returned and bought up everything and put up no trespassing signs. From my perspective so many locusts swarming over the land. Maybe if they were disgusted by trash visitors would not return with the fat bank accounts they earned working for “the man” and displace those already there, by the roots. Now I realize it was inevitable, and they didnt root out all the old timers get, no they needed housekeepers and landscapers and other such of their new “servant” class. Abbey was an influence, after reading his monkey wrench gang I thought it was great to move survey lines, put sand in a bulldozers oil, scatter mining claim markers to the 4 winds. Pretty much nothing but an idiot little vandal. And of course it was useless other than to vomit the gall I felt I was being forced to swallow. Now older and wiser I dont regret my actions so much as now realize their futility.