I always loved wild, open country, from the time I was a kid. I spent much of my youth on a canoe or lost in some forest. It’s why I came West. In 1982, I heard about a new grassroots group called The Southern Utah Wilderness Alliance, I signed right up. Later I briefly became a board member. The idea of “saving the West’ via my involvement in environmental organizations seemed like a good idea to me and in those early years, we were all driven by the same motivations.Going back to 1989, I stated my own reasons why I valued wilderness. In the November issue of The Zephyr, I wrote:

“The concept of wilderness is most troubling to many because it is a radical departure from the traditional American ethic of work and utility. We have been taught that everything has a utilitarian function and if it can’t be used for something, it has no value. But the fact is, more Americans do see a value and are willing to make a sacrifice to see that those wild places are preserved. Whether they get to explore them is irrelevant. And it doesn’t matter if the creation of wilderness areas produces economic benefits to nearby communities, because that is NOT why they were created.”

I really believed this, and my environmentalist colleagues agreed. Our preservation work had nothing to do with ‘selling’ wilderness, it was about saving it. I thought we were on the right side of history. Like the civil rights movement in the 50s and 60s, we were fired by moral and ethical concerns.

Two years after I started The Zephyr, I was contacted by SUWA’s new staff attorney for Moab, Scott Groene. We became instant friends and I admired his dedication and honesty. He was working for about $18,000 a year, but it was clear that, like me, he wasn’t motivated by the pay. We were both a bit over-zealous, I think, but our intentions were good. He asked if he could contribute to the ‘Canyon Country Watchdog’ page. Until then I had carried the load mostly, so I welcomed his help. Within a few months though, it was his (and SUWA’s) column. In sheer space, over a decade, I gave SUWA more than $20,000 in free advertising and I was more than happy to do so. On their web site, SUWA proclaimed The Zephyr, their “favorite newspaper.” (The link has since been removed)

But a hint of what lay ahead came in October 1993, when we were both invited to be the entertainment of sorts for a group of wealthy donors who were being wined and dined by The Wilderness Society. For their significant financial support, TWS had brought these people to Pack Creek Ranch. We got a free PCR dinner out of it, but our conversation with these people left both of us bewildered. Even then, these wealthy patrons supported a massive campaign to create a booming flow of tourists, including more paved roads, more recreational use of the backcountry, and the creation of ‘Gateway’ communities, like Moab, to stimulate a Great American West “tourist/amenities” economy.

When we talked about the need to keep wilderness remote, by keeping access to them primitive, i.e. un-paved, the Big Donors were appalled. “How can we use wilderness if we’re stopped by bad roads in the first place?” We thought that was the point–that you had to work hard to see wilderness, and that even getting to the edge of it should be primitive.

Neither of us was comfortable with the encounter; they seemed to me like a bunch of very wealthy people who wanted to embrace a ‘cause,’ but who didn’t have a clue what they were supporting. They simply liked the idea of being ‘benefactors’ and adding another layer to their self-manufactured persona. Again, MY opinion. I had already expressed my concerns about the gentrification of the rural west in an article called, “New West Blues,” which first appeared in The Zephyr in 1990 and which I re-printed in 1993.

‘The intangible aspect of the West is as vital to its survival as the resource itself. It’s the solitude, the silence, an almost pleasant loneliness that this country evokes in the souls of those that love it. These are an integral part of the West as a state of mind. Abbey could not describe this land without references to the “strange and mysterious” country that he loved so much…”the voodoo rocks.” Even the inhospitable aspect of the West itself became a quality to be admired and respected. You loved the West on its terms and made the sacrifices that were required to be a part of it. Solitude was not something to avoid, it was something to love and respect, and even to depend on. ’Link to New West Blues: http://www.

In the December 1993 issue, Scott would offer his own views when he wrote:

“Abiogenesis (the natural process by which life arose from non-living matter such as simple organic compounds) does not cause Moab tourism. People are drawn here by advertising, guidebooks, and publicity created through travel films, newspaper features, outdoor magazines and the like. And because of the large numbers of people being drawn to the Moab area, frequently, and justifiably, federal land managers now lament the damage being done by too many recreationists. Recreation is like any other public land use: too much in the wrong place can be bad”

Scott concluded, “The BLM will continue to wring its hands about overuse by recreationists. But unless managers get the spine to say no to the causes of too many users, agency staff will get stuck treating the symptoms.”I cannot overstate how gratifying it was to have Scott Groene as an ally in those early days. We both shared a blinder-free view of the West and the impacts that could diminish it, whether the damage came from an oil rig, a jeep or a bike. Or too many motels and second homes. Scott’s denunciation of the National Geographic program proved his willingness to see all sides of an issue, even the ‘motorized’ vs ‘non-motorized’ component of the tourism debate.

Scott concluded, “The BLM will continue to wring its hands about overuse by recreationists. But unless managers get the spine to say no to the causes of too many users, agency staff will get stuck treating the symptoms.”I cannot overstate how gratifying it was to have Scott Groene as an ally in those early days. We both shared a blinder-free view of the West and the impacts that could diminish it, whether the damage came from an oil rig, a jeep or a bike. Or too many motels and second homes. Scott’s denunciation of the National Geographic program proved his willingness to see all sides of an issue, even the ‘motorized’ vs ‘non-motorized’ component of the tourism debate.

THE SUWA BAN ON GUIDEBOOKS & ‘ECO-CHALLENGE’

A year later, Groene and SUWA impressed me even more. The Salt Lake Tribune reported on the growing number of backcountry/wilderness guidebooks being sold and the way different Utah environmental groups were dealing with them. “Within conservation groups,” the Tribune reported, “where-to-go journalism has become a contentious issue. While organizations like the Sierra Club sell trail guides, the Southern Utah Wilderness Alliance will not endorse any guidebook. The decision apparently came after a SUWA official allowed his accolades to be printed on the back of a guidebook. The book revealed details of several little-known hiking destinations in Utah’s San Rafael Swell.”According to the story, Groene explained, “We have not actually come out yet and started burning guidebooks, but given our goals of trying to protect the land, we felt we had to adopt this policy to be consistent in our position.”That said it all and should be as true now as it was 20 years ago. And it’s worth repeating, in BOLD type…

“…Given our goals of trying to protect the land, we felt we had to adopt this policy to be consistent in our position.”

Other local environmentalists weighed in. Moab’s Bill Hedden, now the Grand Canyon Trust’s executive director, said this on GCT’s behalf in 1998:

“Throughout the region…visitation has grown by more than 400 percent since 1980. This surge of interest has coincided with a proliferation of new recreation technologies–some exotic like modern ATVs, humvees, mountain bikes, climbing gear, jet skis and hangliders; and others prosaic like water filters, sunscreen and dry suits. Armed with these new toys, today’s legions of visitors can exploit every niche in familiar areas and enter terrain that previously was protected by remoteness…And though it is common to blame the destruction on a small percentage of lawless visitors, my experience brings to mind the old joke that a mere 99 percent of users give a bad name to all the rest. Make no mistake–we are in this together.”

Hedden concluded, “Everywhere we looked, natural resource professionals agreed that industrial-strength recreation holds more potential to disrupt natural processes on a broad scale than just about anything else. It’s a very tough problem affecting all of us.”In 1995, SUWA would even try to stop a non-motorized event, “Eco-Challenge,” a massive cross-country race across remote areas of southern Utah, that aired on MTV. But the BLM approved the permit anyway. In the May 1995 issue, Scott wrote, “It is no secret that the Colorado Plateau, and the Moab area especially, is at times and places overrun with recreational users…Difficult questions are raised with allocation of diminishing wildlands.” Scott noted, “The race serves merely as a promotional tool for certain products. Race promoters say sponsors include Hi_Tech Shoes, MTV, Jansport, ESPN (and) GT Bicycles…Look for Hi-Tech ‘Eco-Challenge’ shoes and Jansport ‘Eco-Challenge’ packs.”

But Scott and SUWA put up enough of a fight to convince its creator, Mark Burnett (of ‘Survivor’ fame) to never come back. Burnett later told the Salt Lake Tribune that “uncompromising environmentalists cost us hundreds of thousands of dollars and most of our energy,” and said he wouldn’t come back in a million years. Further, Burnett claimed that his race avoided any environmental degradation, and even concluded that they “left the desert in better shape than they found it.”We all thought that was pretty funny and there was some comfort in believing (or at least hoping) that we’d never see their ilk again. SUWA had publicly opposed the recreational commercialization of wilderness, loud and clear.

But Scott and SUWA put up enough of a fight to convince its creator, Mark Burnett (of ‘Survivor’ fame) to never come back. Burnett later told the Salt Lake Tribune that “uncompromising environmentalists cost us hundreds of thousands of dollars and most of our energy,” and said he wouldn’t come back in a million years. Further, Burnett claimed that his race avoided any environmental degradation, and even concluded that they “left the desert in better shape than they found it.”We all thought that was pretty funny and there was some comfort in believing (or at least hoping) that we’d never see their ilk again. SUWA had publicly opposed the recreational commercialization of wilderness, loud and clear.

In Eco-Challenge’s aftermath, Groene even took on ‘Outside Magazine.’ In a Watchdog segment called “Outside is off-base,” Scott wrote:

“I quit buying Outside magazine a long time ago, when it transformed into little more than a plug for the over-consumption of expensive and unnecessary gear and silly “gonzo” activities. I do still read it, standing at the newsstand, to learn which “secret” places have been doomed by irresponsible publicity (unfortunately, southern Utah sites are frequently targeted). Some federal agency staff have also commented about the magazine’s practice of “Outsiding” little known places.

“The August issue reported that SUWA had “threatened to booby trap” the race route for the Eco-Challenge race. I called the magazine to ask for a retraction of the false statement, and they agreed to do so and to publish a SUWA letter to the editor. But when Outside discovered SUWA’s letter was critical of the Eco-Challenge event, it reneged, and said it would not run the letter. It appears the magazine prefers not to risk upsetting any of their advertisers.”

Again, it was comforting to have allies like these guys. In the January 2000 issue of The Zephyr, I listed Scott as one of my real heroes, a man “who could be making the BIG Bucks with some prestigious law firm, but who instead chooses to work long and frustrating hours fighting for something he truly believes in.” And the following July, I called Bill Hedden one of Moab’s ‘Top 10 Highlights,’ when he filed for a County Council seat. I wrote, “He served bravely and honestly for four years and now returns to the political ring. Anywhere else in America, Bill would be our U.S. Congressman–he’s that talented.”

A TIDAL WAVE OF CHANGE…

But somewhere along the way, our philosophies diverged. For decades I didn’t know why, but the wilderness road that we had all been traveling, suddenly forked. They went one way and I went another.

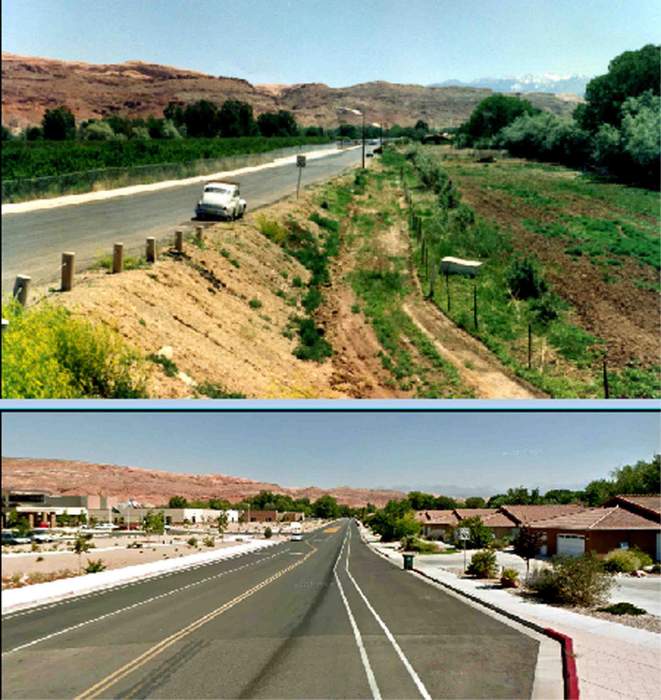

As the years rolled on, and we moved into the late 90s, I became more alarmed by the effects of the recreation/amenities economy. I also realized how SUWA and other conservation groups were paying less attention over time to the inevitable impacts that this “new economy” was creating. Each contribution to The Watchdog was a repeat of the issue before it—the targets were, without exception, about oil and gas, mining and grazing. Their one concession to recreational impacts was their non-stop reporting of ATV abuse, a serious issue to be sure. But the changes being wrought by the new amenities economy went far beyond the tracks ripped by fat tires. And they knew it. It was as if they had reverted to 1985. Nor could they see the connection between energy exploration and development and a tourist/recreation economy that demanded energy just to get them here.

The first crack in our shared philosophy seems minor, relative to what’s come since, but it marked the shape of things to come. One day in late 1999, I was having coffee with a friend and she described a ‘backcountry tour’ she’d taken with a new ‘canyoneering’ company. She talked about a remote area in Arches National Park, where she’d hiked with a small group to an unnamed arch that perched on the edge of a deep canyon. The “tour” included a rappel to the bottom of this deep crevasse and cost $160. My curiosity was aroused; it sounded so familiar and the next day I confirmed my worst fears, when I hiked out there myself and found the riggings and ropes and hardware that had been left behind but in place for the next commercial tour.

For the entire story:

ARCHES, LOOPHOLES & the NPS

A weak climbing policy and a non-existent commercial permitting system do a disservice to the Arches backcountry…by Jim Stiles

http://www.

Even if the NPS refused to see the problem, I was sure SUWA would. I contacted Moab’s most recent staff attorney, an affable fellow named Herb McHarg. We met at the Red Rock Bakery and I told him about my discovery. I expected him to blow a gasket. But instead he smiled and said, “Well….look. We can’t be against everything.”I was surprised. It never occurred to me I’d need to convince Herb or anyone at SUWA that there was a problem with this kind of activity. I argued that if SUWA picked and chose its issues, they’d lose credibility. Later, I noticed that Desert Highlights had become a “proud business member of the Southern Utah Wilderness Alliance.” I contacted other SUWA staff, sure that somebody would be incensed once they got the details, but they could not have been less interested.

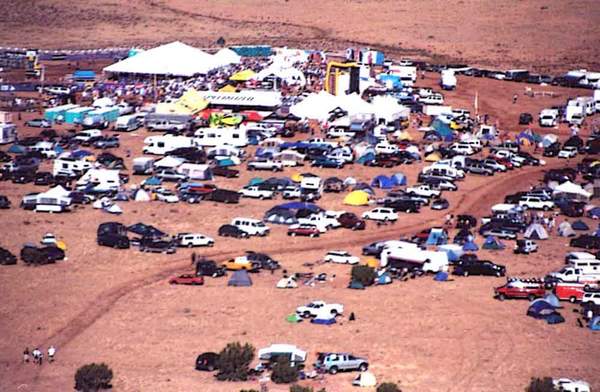

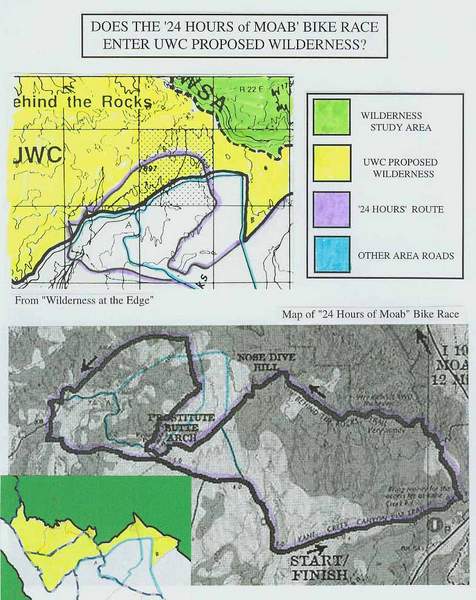

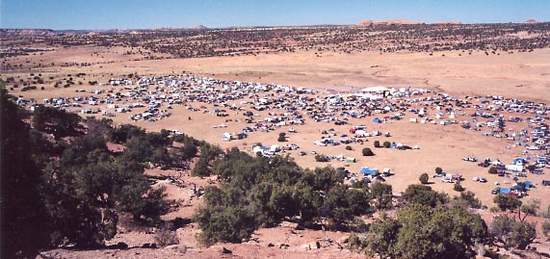

Other events came along that would have drawn SUWA’s ire just a few years earlier. The ‘24 Hours of Moab’ bike race, a carnival-like event that involved thousands of bikers on land just inches for SUWA-proposed wilderness, which would have aroused SUWA scrutiny just a couple years earlier, was all but ignored. In fact, after the first race, in 1994, SUWA did comment negatively in its Zephyr ‘watchdog’ column, but within a few years, SUWA failed to even send a monitor. When I emailed the SUWA representative in Moab, she’d even forgotten the race was taking place.

Later, a careful study of the race map and of SUWA’s wilderness proposal even proved that, in the early years, the race was executed ON SUWA’s proposed wilderness lands. They angrily denied my assertion until they finally looked at the maps. Later, SUWA actually removed the contested land from its proposal but insisted the change had nothing to do with ‘24.’

The story is recounted here, in this 2012 Zephyr essay:

THE VIEW FROM ABOVE: 24 HOURS OF MOAB

http://www.

Still, despite the continued lack of concern, I remained tenacious–annoyingly so, I suppose— and when I persisted, I could see the bewilderment on their faces. My friends at SUWA were shocked; it was as if I had turned on a friend. Their cheery email replies to my hard questions almost bordered on the surreal. It was as if I’d attacked the infallibility of the pope, and rather than deal with it, they’d just pretend I hadn’t said it.

What they couldn’t understand was that, as a journalist, I felt it was wrong to let friendships sway an objective analysis of the facts, regardless of the consequences. Further, I could not understand why honestly disagreeing with these people that I believed to be true fair-minded liberals might jeopardize our friendship in the first place.

But that’s what happened. Their initial bewilderment gave way to annoyance and then open hostility. For me, it was one of the most discouraging times of my life. I had for years believed we were all on the same team, and clearly we were. But somewhere along the way, the mainstream environmental ‘movement’ moved away from the moral high ground and chose a different path. And, like everything, this movement had to do with money.

Within years everything changed. In 1994, SUWA staffers had adamantly opposed guidebooks and Groene had publicly worried about overexposure from television promotions that might “draw more visitors than the land can handle.” But later, the SUWA board reversed the ‘no guidebooks’ policy and the staff went along.SUWA even got into the guidebook act itself when it sponsored and promoted a number of slide shows by “legendary backcountry explorer and prolific guidebook writer Steve Allen.” (Redrock Wilderness Newsletter).

Allen called his show, “Canyoneering Chronicles” and he took it to nine different cities in Utah and Idaho, as well as New York City. In a related Salt Lake Tribune story, titled “Canyoneering Allen Says More People Should See Wilderness to Save It,” Allen insisted that a mass influx of non-motorized tourists to wilderness areas was the only way to preserve our threatened wildlands. “We need more people out there, not less,” he said. “Right now, the wilderness lands are in flux. They’re embattled. We need as many supporters as we can get…If places get too crowded, we can take appropriate steps (to limit access).” Again, no one in the environmental community stepped forward to challenge Allen’s strategy. Groene’s fears of “overexposure” were a thing of the past.

TIME TO LOOK IN THE MIRROR…

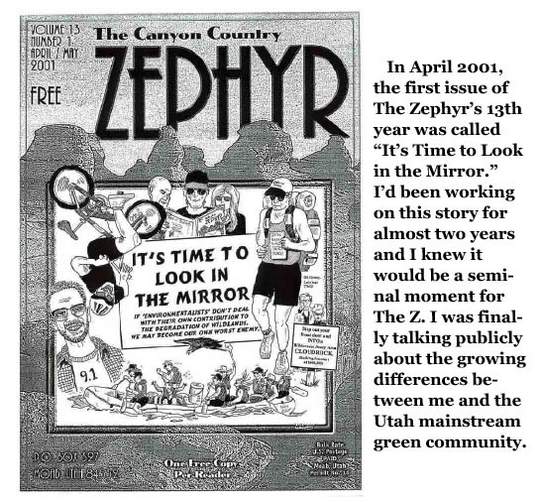

In April 2001, the first issue of The Zephyr’s 13th year was called “It’s Time to Look in the Mirror.” I’d been working on this story for almost two years and I knew it would be a seminal moment for The Z. I was finally talking publicly about the growing differences between me and the Utah mainstream green community. It was not, as they would later claim, a matter of me waking up one day and ‘trashing’ them. I had worked behind the scenes to create some kind of conversation but it went nowhere. Finally I was ready to talk about these issues in a public forum. Here is just a short excerpt from my Page 2 editorial from April 2001…

‘Recently…the Salt Lake Tribune suggested that, “…while they (environmentalists) were battling the cattle ranchers, oil drillers and loggers, they overlooked another threat that can wipe out an area’s wild character as effectively as a clear-cut: Themselves.”‘

To me, it at least offered an opportunity for some honest soul-searching. But the Southern Utah Wilderness Alliance’s response was, to me, discouraging. “While we agree that all of us have an impact on the land,” SUWA’s newsletter replied, “the difference between hiking and clear-cutting is profound. Implying otherwise suggests deep-seated, dogmatic opposition to the efforts of environmentalists.”

Of course, we all know the difference between a clear-cut and a footprint. But how about a billion footprints? Or ten billion? How about well-intentioned, self-proclaimed environmentalists moving by the millions into the ever-dwindling habitat of the ever-encroached wildlife? How about the exploitation of wildlands by a whole spectrum of non-motorized recreational entrepreneurs who can gain absolution from environmental groups by making a generous donation or by paying lip service support to a particular piece of environmental legislation?‘Or how about a funky little bi-monthly publication that complains about all these abuses and yet survives on the advertising revenues of some of those very same companies?’

Finally…

“Environmentalists can no longer ignore the invasion around us and pretend it’s still 1975. The times have changed and the culture has changed. “Wilderness” is still just as important as it ever was, but saving this land is so much more than that. One of my friends put it best: “When the population of Utah grows so much and changes so much that its Senators actually want a big wilderness bill, it’ll only be because we yuppies moved in and took over the state…and that’s when I’d have to leave.” Isn’t that weird? And I’d be right behind him.”

http://www.

When Will Environmentalists Acknowledge Their Own Contribution to the Destruction of the Wilderness They Claim to Love & Want to Protect

http://www.

As the U.S. Population Approaches 300 Million, Guidebooks & TourGuides Have the Potential to Turn the Backcountry Into a Nightmare. And It’s Only the Beginning

http://www.

How does a recreation-based company honor its commitment to environmental values?

http://www.

In the next issue, the response to the “Mirror” edition was phenomenal. I’d never received so many intelligent, thoughtful, self-scrutinizing letters from readers. They weren’t all supportive but they were all constructive. Missing, however, was any comment from the mainstream environmental community. Nothing at all. It was my last gasp at opening a discussion

Here is a link the ‘FEEDBACK’ from the June/July 2001 issue:

http://www.

A year later, SUWA produced a special “Wilderness and the Economy” issue. The feature story was called “The Local Economic Impacts of Protected Wildlands: Enhanced Economic Vitality.” It was written by Thomas Michael Power, a Professor of Economics at the University of Montana.

Power and his data asserted that protecting the rural West’s wildlands did not damage local economies; on the contrary he believed that “protected landscapes are often associated with enhanced economic vitality.” But he followed that declaration with a curious caveat, considering the intent of the article, that was all but ignored by environmentalists. Power warned:

“This does not mean that those seeking to preserve natural areas should base their case for preservation on the economic expansion it will stimulate. That could be a dangerous strategy in the long run and one that may not be very convincing besides. In fact, in the long run, ongoing economic growth may well threaten the ecological integrity of wildlands as growing population, human settlement, and commercial activities and their accompanying pollutants isolate and disrupt natural areas. Even though wildlands may be good for local economic vitality, local economic vitality may not be good for the ecological integrity of those wildlands. “(Emphasis added)

Power concluded, despite his early warning, “It is not clear why wildlands advocates would not want to meet the economic critics of wildland protection on their own ground, while also continuing to make the ethical, cultural, and environmental arguments. After all, if you can take away the only powerful argument the anti-environmentalists have, why would you not do so?”

Power concluded, despite his early warning, “It is not clear why wildlands advocates would not want to meet the economic critics of wildland protection on their own ground, while also continuing to make the ethical, cultural, and environmental arguments. After all, if you can take away the only powerful argument the anti-environmentalists have, why would you not do so?”

I emailed then-executive director Larry Young to express my concern. I wrote,“…after reading the latest ‘special edition’ of the SUWA newsletter, it seemed to me that the environmental community embraces the kind of growth we’re seeing in rural Utah as a good thing. As a real plus instead of any kind of liability. The section on the economy said exactly that, and without hesitation or qualifications. It was citing the same sources to PRAISE the growth and changes in rural Utah that I used to express alarm.”

Young’s reply was quick and personal.“I think I sleep more peacefully as Executive Director of SUWA than I would as Publisher of the Zephyr. Why? …the cumulative advertising within each issue of the Zephyr constitutes a far more aggressive call to intensive recreational use of southern Utah, a far more aggressive celebration of the yuppification of southern Utah, etc. That doesn’t mean that the Zephyr lacks a conscience or the capacity to do good. But it is difficult for me to see how you can be more disappointed by SUWA than by yourself.”

I was amazed. I pointed out that The Zephyr had, in fact, a paucity of recreation-based ads, about THREE, simply because I’d made most of my potential ad base mad with my “anti-development” editorials, that I didn’t accept corporate ads at all, that I wasn’t funded by billionaires, and I even proposed that I publish The Zephyr’s and SUWA’s IRS 1040 tax statements, so that readers could judge for themselves.

Young backpedaled, conceding that, “This is something many of us in the conservation community are aware of –and one of the reasons I have always had a great deal of respect for you.”He added, “I wasn’t attacking the Zephyr or the folks who advertise in the Z (as I said in my last email, some of your advertisers are friends and I greatly value the support that many of them give SUWA). In fact, I love the Zephyr and I think it serves an absolutely critical function.”

Young agreed that, “SUWA should engage in the kind of self-examination you are calling for. I will feel like I have failed if I don’t help us do that in a newsletter within the year. We are already doing some of that in board and staff meetings. Still, we aren’t doing enough.”It was a start, but it was just words; nothing came of it and a year later Young left SUWA. His replacement would be my old friend Groene.

Before he’d even returned to SUWA (Groene worked briefly for the Greater Yellowstone Coalition), I’d sought his advice. Frustrated with SUWA’s refusal to deal with these kinds of growing recreational impacts and even the hostility that my persistence had caused, I turned to the one person I thought would see the bigger picture. We’d clashed on amenities issues before, especially in the last couple of years, but I thought we’d find common ground this time. I sent him a copy of a story I’d written about the canyoneering controversy and waited for his response.

But his reply was vague. “This is good, “ he said, “and something The Zephyr should be writing about.” But when I pressed him about the canyoneering debacle and SUWA’s lack of interest, he gave me an answer that I didn’t see coming.”I gave you a non-committal answer,” he said, “because I could see you were just fishing for a chance to beat up on SUWA. Like a pitcher that licks his fingers with every curve ball, you tend to signal in advance upcoming anti-SUWA tirades. We’ve trod that ground, over and over, without satisfaction on either side- I like them as individuals and as an organization, and have no interest in trashing them.”

I explained that I wasn’t on a “tirade,” or trying to “trash” or “beat up” on anyone. I thought that I could disagree, without becoming an enemy. It made no sense.

But by 2003, when I wrote about the “24 Hours of Moab” race that sent 5000 bicyclists within inches of proposed wilderness, Groene was now back at SUWA. I asked for his comments and, for me, they represented a sea change. While he offered, on one hand, an olive branch, proposing we simply stop talking about these issues, he wrote, “Let’s be honest: this email you’ve sent is nothing but part of your effort to demonize SUWA… I would have never thought that I would get fairer treatment in the San Juan Record than the Zephyr, but sadly that’s become the case.”

Groene and others insisted that I had suddenly “changed,” that I had awakened from a dark vision and decided my single goal in life was to “demonize” my old friends. But it just wasn’t true. As I’ve re-read these old emails and Zephyr issues from the past 25 years, it’s clear that somewhere in the early 2000s, a strategy emerged that shifted the quest for wilderness from a moral and ethical issue to an economic one. It required the almost total abandonment of recreation/tourist/amenities concerns that might hinder or restrict an unchecked recreation industry.

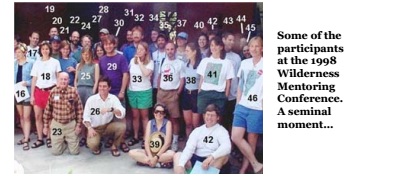

More than a decade later, I would accidentally stumble upon an ancient web site called, “The Wilderness Mentoring Conference of 1998.” It filled in the missing blanks and explained finally why there had been such a sudden shift in strategy. Or at least the beginnings of one.

I learned that on Memorial Day Weekend in 1998, according to the document, “sixty-three people active in (or suffering a tenuous retirement from) wilderness advocacy met at the Rex Ranch in Amado, Arizona, for the first Wilderness Mentoring Conference.” It included participants from national and regional environmental organizations coast-to-coast, including The Sierra Club, Montana Wilderness Association, Alliance for the Wild Rockies, Friends of Nevada Wilderness, Southeast Alaska Conservation Council, and National Audubon Society. And it included representatives of the Southern Utah Wilderness Alliance (SUWA), including its then-Executive Director, Mike Matz. Matz would also preside over the conference as one of its mentors.

I wrote this about the conference:

‘It brought together, the introduction explained, “the last generation of ‘closers,’ those who know how to take an idea and run with it all the way to the president’s desk, with a new generation of eager, thoughtful wilderness advocates. The younger generation was encouraged to think critically and to identify strategies, tools, and tactics for developing and leading successful wilderness campaigns.”

‘A prominently displayed quote by Michael Carroll, now of The Wilderness Society, established the tone and direction of all that would come later:

“Car companies and makers of sports drinks use wilderness to sell their products. We have to market wilderness as a product people want to have.”

‘That, in its most succinct essence, was the theme of the conference. While the organizers of the event paid tribute to the wilderness activists who had come before, clearly the purpose of the meeting was to propose a new approach. “Although it is important to pioneer new wilderness strategies,” the report explained almost as an afterthought, “we must do so with knowledge of what has come before.” With that token nod to the “importance of history” and to the “philosophical and political contexts” of the wilderness movement, the conference explored the new territories of salesmanship, marketing and media manipulation to win the legislative wilderness battle. One might think you were being taught how to sell a new Buick.’

Here is a link to the story I wrote about it:

“Thoughts on the Wilderness Mentoring Conference of 1998″

http://www.

And excerpts from the Mentoring Conference:

http://www.

Almost 15 years later, I’d finally understand what happened, or at least what started the transformation. It might have been less painful if SUWA et al had just admitted the strategy shift and moved on. Instead they insisted that nothing had changed at all. It’s like the kid who gets caught with his hand in the cookie jar, evidence in hand, and insists, “I don’t know what you’re talking about!”

The Zephyr’s biggest sin was reporting these changes as they occurred. We’d never called anyone names, never attacked them personally. Our quotes were accurate and so were our facts.

In the future I’d run into the same problem when I confronted mainstream environmentalism’s growing dependence on some of the wealthiest bankers and capitalists on the planet who support their conflicted causes. The money often gave these rich people—the 1%— undue power as well, via positions on boards of directors. The environmental groups insisted there was nothing wrong with their billionaire-funded largesse, but were furious that I’d reported it. It was the other ‘missing link’ in understanding why everything had changed so quickly.

It was clear to me, for better or worse, this little rag had chosen a road less traveled. One thing was certain—we weren’t doing this for the money.

NEXT ISSUE: MONEY MATTERS…Grass Roots Environmentalism Goes for the GREEN

Click Here to Read The Zephyr Chronicles #1: The First 25 Years, Pt 1…by Jim Stiles

Jim Stiles is the Founder and Co-Publisher of the Canyon Country Zephyr.

To read the PDF version of this article, click here, here, and here.

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!

![]()

Hi Annie…Thanks for your comments. But I want to make sure you understand— I never suggested that “malice” was their motivating factor, though they did direct some malice at me and this publication for disagreeing with them. You’ll understand a lot better when the next installment comes out in October.

But in the late 1990s, these grassroots groups suddenly found themselves the beneficiaries of a LOT of money…revenues they never dreamed possible. But with those kinds of donations, always come caveats. The newfound benefactors became board members and began to dictate policy. Remember SUWA’s opposition to guidebooks? After Wyss, Fingerhut et al took over SUWA’s board, the staff was forced to denounce its own core beliefs. The Money Talked and that’s where things began to change.

You’re right…It was NOT ‘out of the blue.’ Events happened, new board members pushed their own agendas, enviro staffs were rewarded with massive increases in salary, and the emphasis became—‘wilderness pays.’ The economic component became the driving force. And what else would you expect when your boards of directors are comprised of some of the wealthiest, and sometimes ruthless, venture capitalists, industrialists, bankers and financiers on the planet?

And finally, re: your reference to David Brower—you’re right, he made compromises, especially giving up Glen Canyon. BUT, like you noted, it didn’t take long for him to regret his decision. He openly admitted his mistake, suffered badly for it, and he flogged himself for the rest of his life. I don’t see even a hint of that kind of self-scrutiny within the mainstream environmental community.

I think the next installment of The Chronicles—“Money Matters”—will explain further the transformation. Thanks again for your comments…Jim

Bravo Mr. Stiles. Nuff said.

As always Jim, you nail it. The recreation/amenities economy is destroying the very thing we came here for. If it were as simple as monkeywrenching a few bulldozers, that’s one thing – but how do you take on 5000 mountain bikes or the companies that sell overpriced and unnecessary gear that use “Wilderness” to promote their product. I consider the Moab area a National Sacrifice area now. SUWA lost all my support in the early 2000’s…. and that after sending them a lot of money. Sigh….