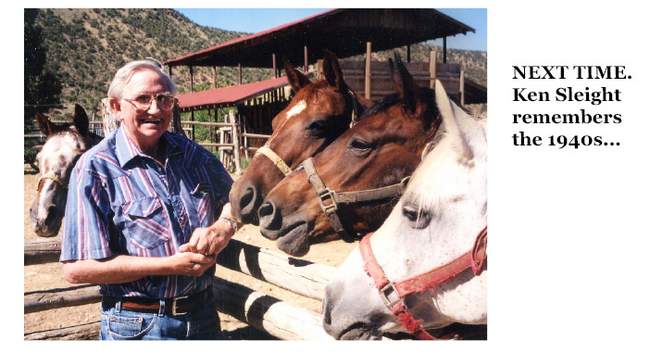

EDITOR’S NOTE: For years, Ken Sleight was a regular columnist for this publication and his topics scanned the spectrum—from his passionate quixotic quest to restore Glen Canyon, to his opposition to nuclear waste in San Juan County. Ken also took the time to recall the events and times of his own life. Many of those stories were written in the pre-internet era and only those few who saved the old paper Zephyrs would ever have access to them. But now we’ve begun the long and arduous task of transcribing the old stories and re-posting them here in digital form. This is the first of a series of, until now, lost stories by our friend and mentor, Ken Sleight…JS

We didn’t enter this world voluntarily; we each entered it guiltlessly alone. New and fresh beginnings now await us in our new millennium, and a brief historical reflection might be in order before we begin that journey. And so I pause to celebrate and share my own rustic beginnings with you knowing that we each have a most unique connection to our blessed earth, ourselves, our family, and our community.

My reflection begins with Thomas Sleight, a low-land swamp farmer from Lincolnshire, England, who converted to the Mormon Church and sailed to the states in 1854. He settled Genoa on the old Mormon Trail in Nebraska in 1857 until burned out by the Sioux; traveled by wagon train to Utah in 1860; helped colonize Cache Valley; and in 1863, after the Bear River Massacre had lessened the Indian threat, he uprooted again at the direction of Brigham Young, to help settle Bear Lake Valley.

Of the original pioneer party, Thomas Sleight built his one-room log cabin in Paris, Idaho. [The house is a tourist attraction today across from my dad’s old warehouse, now housing the Idaho State Parks.] Paris is located in the most southeastern county of the state. There he set up a farm on Paris Creek and with others grubbed and cleared the sagebrush-covered hills and valleys.

As Thomas’ first wife had recently died, he married the fourteen-year-old daughter from the polygamous family of Solomon Wixom. From that arranged marriage came my gentle grandfather, George Sleight, who had married the feisty Emily Miles, the daughter of a former sailor, London pub owner, and polygamous prisoner John Horne Miles.

From that contested marriage, my father was born in 1903. He also made his home in Paris, a small town of about 700 people or so.

In the prosperous decade of the exciting twenties, industrialists and the government were having a heyday. The enormous factories could not turn out consumer goods fast enough, producing more than the American people had money to purchase. It was an age of bigness, prosperity, and optimism—the era of J.P. Morgan and David Rockefeller. However, in Bear Lake and many other rural areas, farming had been in a deep and prolonged depression for some time.

My father, his bent to the commercial, looked forward to a hoped-for prosperity. He had married Orletta Peterson, an attractive farm girl from nearby Ovid in November 1925.

Dad entered the feed and grain business utilizing an existing small store on main street. While there, he also built a log house across the street from it where I was born in 1929. I joined an older sister, Maxine.

Dad’s rural business prospered and he began making money. Able to obtain financing, he built a large warehouse to store the grain and to provide the necessary services.

During this time our little log home burned down. Dad met this awful disaster by quickly converting a part of the new warehouse to a “temporary” upstairs apartment. This was to be our frugal home for the next ten years.

Trouble loomed on the horizon however. On October 24, panic spread in the eastern money markets. The terrifying “Black Thursday” shocked the nation and the prices of stocks and bonds crashed. The following Tuesday the market collapsed completely. There were many bankruptcies, foreclosures, and bank failures. Millions were unemployed and lost their life savings, homes, and farms. The depression spread worldwide.

Bear Lakers were not immune, as the crisis hit businesses throughout the valley and some went under. Dad’s business was also in serious trouble. He had extended himself financially as far as he could, and with a growing family the crash placed a growing hardship on all. However tough the conditions, he found the ways and means to stay afloat and convince his lenders to stay with him.

In this setting, in 1929, I started on my own life’s journey—a varied one indeed.

A harsh disciplinarian, Dad tried not to allow any of us kids to stray. He did this by keeping us busy, and the jobs he assigned us created even more jobs. At my young age, I often aided the hired help with the dirty job of hauling coal. We shoveled the coal from the rail cars in Montpelier, loaded it onto the truck, delivered it to our customers, and dumped it in their coal chute.

I helped grind, clean and bag the grain. Many hours were spent in mending burlap sacks—by sewing or by mixing up a flour paste and ironing burlap patches onto the grain sacks.

In January 1931 my busy mother bore twin bows, Ray and Roy. She labored long hours in rearing the four of us while also helping tend to the demanding business.

Relief problems persisted. The caring of human needs centered mainly on our church, private charities, and the government. The Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) and the WPA program also brought needed jobs to the county. I remember the workers gathering at our warehouse with their shovels and tools in hand for transport to the road-building projects. Many of the dirt roads had not been been graveled, yet alone paved.

My first years were spent in the act of growing up.

But not all was rosy. At the age of six, in 1936, just before starting school, I contracted pneumonia and was in the Soda Springs hospital and ill for some time. Pneumonia was usually fatal and sulpha drugs or antibiotics were not yet available. I think my folks had given up on my pulling through. My family once came all together to see me, and they seemed sad-eyed. The solemn-looking church man prayed over me. Dad gave me an erector set; the elation I felt on receiving it probably pulled me through, fooling them all.

The effects of the pneumonia stayed with me. On entering school the teachers found I couldn’t see the writin’ on the chalkboard so well. It all looked fuzzy. Dad took me to Pocatello where I was tested and fitted with eye glasses. My first trip out of Bear Lake Valley proved successful. On my return, my classmates taunted me for a long time as I was the only “four-eyes” in the school. Soon after getting the glasses, I broke them in a hellish fight and got further hell when I got home, but from it I won another trip to Pocatello. I’ve worn glasses ever since.

School continued to be tough. One day, I forgot my book and assignment, and the teacher ordered me to go back home to get them. I left the school but didn’t go back home. Instead, I took off for the hills. Above Stucki Hill, where we sledded on our Flyers in the winters, I roamed about the old burned-out Fielding Academy, a Mormon high school my folks had attended. My infamous and harsh great-grandfather John Horne Miles was superintendent at the time it burned. Hiking about all day and enjoying the short period of outdoor freedom, I returned home in the afternoon when dutifully expected. This escape mechanism was repeated on special occasions when needed.

As my mother had so much to do, she handed me over to my loving and aging grandparents Peterson in nearby Ovid for them to help raise me. Over the decade, I came to be as much a part of the Peterson family as the Sleights. Grandpa was of Danish stock and Grandma a mixture of Swedish and Norwegian. Their sparse income derived mainly from egg and milk production. Though they worked hard, they were very poor. I didn’t realize that then.

Their house, a small two-roomed log cabin, stood on a slope overlooking the beautiful fields. I lived in the front room which included the kitchen. The separating door to their smaller cramped bedroom in the back was usually shut to preserve heat and to prevent my entrance. They had no indoor plumbing; the water had to be carried from a shallow well a hundred feet away.

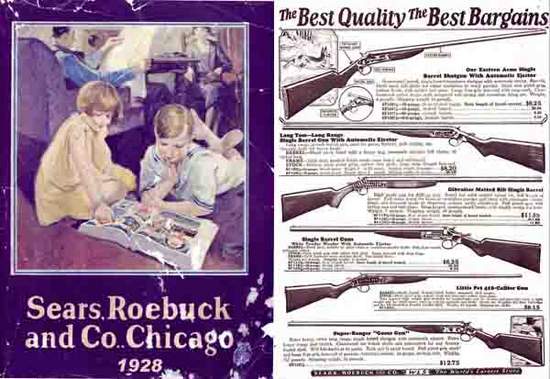

An outhouse toilet stood at a couple of hundred feet overlooking the barn yard. A quaint two-holer, it accommodated the many grandkids that came to visit. For toilet paper the pages from the Sears, Roebuck catalog or the “Monkey Ward” catalog sufficed. The pages were great for making paper airplanes and sailing them out the doorway.

They had just recently hooked up to the phone service. I remember the old party-lines with up to a dozen families sharing one line. The phone twang away, as we listened for our designated code—the number of long rings and short rings—to see if it rang for us.

Grandma liked her soaps and the Mormon Tabernacle Choir. Rex Campbell’s KSL news reports opened by a rooster crowing. In the evening I listened to Tom Mix and Jack Armstrong. At night, when it was quiet, I would turn on my treasured crystal set with earphones and listen to cowboy songs till sleep came. I slept on a makeshift couch in the kitchen that doubled as a seat during the day. A thick quilt that grandma had made covered the sagging bed and always smelled of the odorous barnyard.

A wood stove heated the cabin. I kept the woodbox full. As we couldn’t afford coal, we did our own wood gathering and hauling. I would take my turn at sawing when another kid came to visit—the saw having a handle on each end. Later, as I grew older, I went with grandpa to cut the trees and snake them by horse to the wagon. We’d cut them into firelogs later.

Grandpa would often take me with him on his coal-black mare, “Lady,” to round up the cows, though his yelping dog would do most of the work. I rode behind grandpa, my arms tightly clutching his waist. After the roundup he’d let me ride Lady by myself around the yard while he prepared the cows for milking. He required that I’d ride bareback when alone. “It’s safer,” he’d always say. But I still longed for a saddle like that pictured in the Sears Roebuck catalog. Sears Roebuck bib overalls served as my working attire, just like Grandpa’s. These durable denims lasted longer than any other cloth and had plenty of pockets. Later, I demanded authentic hard-working Levi’s like real cowboys wore.

I followed grandad down to help milk the cows. Even though my hands weren’t large or strong enough at that time, he let me strip a few. After we separated the milk, he’d cart the cans of milk and cream out to the county road for pickup by the co-op creamery. We farmed with horse-drawn machinery: mowers, rakes, wagons and a number of home-made appliances. A team of strong horses and a couple of riding horses provided the power.

One day as I tromped hay on the hay wagon, while Grandpa forked it to me, the horses started off on their own and they soon stampeded down the field, the loaded hay wagon and the excited-me behind them. I knew, even at that young age, that if the horses took a sudden turn, the wagon would flip over. Round and round the hay field they ran, the wagon rocking and bouncing up and down, and grandpa breathlessly running far behind, waving his arms up and down, and yelling, “Whoa, you sons of bitches, whoa!” until the snorting horses finally stopped from total exhaustion after their mile-long run.

A most delightful job, I would get on old Lady and drive the cows and heifers down a narrow dirt road about a couple of miles to the bottom lands. Each morning I’d trail them down, and each evening I’d trail them back. Sometimes I stayed with them—an endearing time as I enjoyed being alone, the quietness about me, and my thoughts to myself.

I’d often ride about the swamp lands before turning home. Willow thickets and dense stands of bulrush and cattail housed many nesting birds. Birds with long legs and slender pointed bills waded and probed the shallow water. Canada geese, canvasback and redhead ducks, and the white-faced ibis passed in review. Songbirds—the meadowlark and the killdeer—sung to me. I came to love all wildlife as I felt freedom along with them.

I rode Lady through the marshes, only to find the waters deepen in places. The water covered my lower legs as Lady jumped or swam to shallower waters or to the land and I hung onto her long mane. When Lady foaled late one summer, I continued riding to the bottoms. But leaving her cold behind made Lady extremely nervous and eager to return to the barnyard. On my return one day, she changed her smooth and easy gallop to a race-horse gait. At a sudden 90-degree bend in the roadway, Lady made a quick left turn, but I kept going straight and hit the dusty road. When she realized I had taken a dive and was no longer on her back, she suddenly stopped, turned around, and trotted back, and looked at me as if to say, “What’s a-matter, kid?” She let me cautiously remount, but needless to say, I kept her to a reasonable gait—walking–on our return home.

These times in Ovid brought me to a realization of the real beauty of the earth and its diversity—the mountains and the rivers and the swamps. This is the raw stuff that I encountered. Each millennium, century, year, month, day, and hour brings a new beginning and a new adventure, unique to each of us. And with it comes the comforting knowledge that we’re all connected to the earth, to ourselves, to our family and to our community. What a heritage we have to build upon.

To read the PDF version of this article, click here.

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

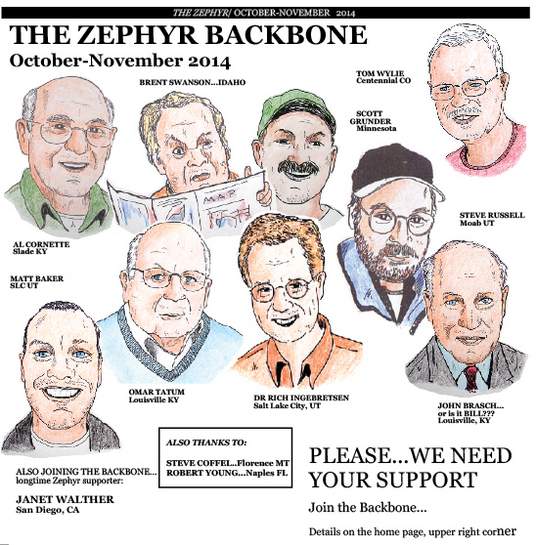

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!

Thank you for this series. I met Ken, along with Ed Abbey, one summer afternoon in Green River, Utah, where the warehouse for the company I was rowing for – Holiday – was located. All this is especially poignant today with the news that Dee passed away last night.

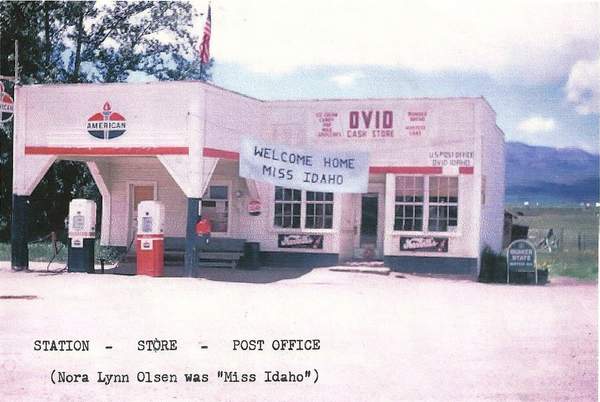

I grew up in Paris, Idaho with neighbors Jay and Weldon Sleight who labored long hours at their father Roy’s feed store on main street. I played around that old log cabin without ever knowing its historical significance. Miss Idaho, Noralyn Olsen Petersen, was in my grade. As a lad I was a “Home Teacher” for grandma Sleight who cooked a wood stove 365 days a year, but never got to see her during the winter because she went to bed when the sun went down. Now I need to look at the Sleight family tree to see how Ken fits with Roy and Ralph. Ken’s geography and history sure rings true with my own childhood memories of Bear Lake.

Hello! Are you from one of the Tippets family that lived in Georgetown? If so all my Tippets families would love to hear any stories you might share of growing up in this area of Bear valley!

Thanks David Tippets for sharing this wonderful piece with me. (I grew up in Bear Lake Valley, except for a 5 year hiatus in…Moab from ages 5 to 10 years old! So this was a double treat, walking down memory lane.)