Gail and I found the hamlet of Ruth, Nevada, on U.S. 50, 82 miles west of the Utah border. This tiny village is dwarfed by the massive outer shoulders of the Robinson open pit copper mine, just as mining towns everywhere seem to exist within the maw of the mines they serve. Yet Ruth also lies on the visible edge of 250 miles of the widest open of our wide open desert landscapes, heading crazily west through remotest central Nevada.

After witnessing Ruth and the mine hulking over it, we gazed westward into the blazing heart of big time biker country.

The Robinson copper mine is enormous, employing almost 600 people and in 2009 producing the great majority of Nevada’s copper, along with some gold, silver, and molybdenum. If we assume this mine has 590 employees with an average salary of $42,000, it’s been bringing over $20,000,000 a year into the economies of nearby Ely, population 4300, and of course Ruth itself, population 440. More than enough to generate plenty of boosters locally.

I live in West Virginia, where we feature the special horrors of mountaintop removal mining, and also deep coal mining, which by contrast is merely poisoning our plentiful streams and rivers and otherwise befouling our state. My point is that, yeah, copper mining is different from coal mining, but when you boil it down mining is pretty much mining wherever you go; that there’s an essential set of experiences. And since I’ve worked as a mental health and addictions counselor with my share of coal miners, I think I can say something about the struggles and ironies miners face regardless of geographical setting.

There are three facets.

The first is what mining means financially to a young person just out of high school. With sufficient training as an electrician, mechanic, driller, truck driver, etcetera, a miner can make enough money to comfortably support a family on one salary, especially in the rural areas where the mines are likely to be. And this is without incurring the huge debts that are now necessary to pay for college and professional school. Given the near universal erosion of unions and the globalization of so many manufacturing and other jobs, a career in mining has strong appeal to a young person with few choices.

The second facet is that mining remains a dangerous job. Miners still get killed sometimes, and while those deaths often make the evening news, the innumerable broken lungs, twisted backs, and otherwise damaged bodies that so many miners incur don’t receive press coverage. The rural primary care clinic I worked in for 12 years was replete with miners suffering from chronic maladies.

- Most of us have at least heard of black lung, which results from repeatedly inhaling coal dust in deep coal mines, mangling the miner’s capacity to breathe. And while the risks involved in chronically inhaling copper dust and other rock dust or being exposed to them in an open pit copper mine may be less drastic, they’re undoubtedly significant.

- Back, neck, and leg injuries from a variety of work-site mishaps, accompanied by chronic pain, is common throughout mining. I spent much of my time in counseling trying to help miners figure out the skills that would allow them to live with chronic pain without getting hooked on opiate pain medications. If a miner has sufficient motivation it takes about two to three years of struggle to adapt to chronic pain and to figure out how to cope with it.

I liked the miners I worked with and admired their fortitude in the face of pain and disability.

In a way, becoming a miner is a set-up. Because most young people enjoy such vigorous health they can have difficulty imagining that terrible health problems can actually descend upon them over time, even when they see that happening to older people they work with. Even less do they contemplate what it’s like to have the medical and mental health treatments that they need be politely blown off by a privatized state worker’s compensation program, or to endure a protracted social security disability claim.

There are, of course, young people who see all this coming, perhaps from family experience, but who nevertheless calculate that all that money is worth the risk.

In either case, what becomes devastatingly clear to miners as the years on the job pass by is that all along the price of providing their families with a comfortable way of life was putting their health at significant risk, and this is true even where the mine does what it can to make the operation safe (which I assume the Robinson mine does). Certainly miners hope they’ll be fortunate enough to retain vigorous health into old age, but are nevertheless aware, and likely their families are as well, that there’s a good chance they won’t. At all.

The third facet is ironic if not paradoxical: that in spite of the way their work mars the land at least some miners bond on a personal level with the woods and streams or mountains and deserts within reach and know the experience we call solitude. Let me undergird this point by quoting Jim Stiles: “But Old Westerners understand one key component of wilderness far better than their [environmentalist] adversaries. They understand solitude, quiet, serenity, the emptiness of the rural West. They like the emptiness.

“New Westerners are individually more sensitive to the resource but are terrified of solitude. They’ll walk around cryptobiotic crust, but leave them alone in the canyons without a cell phone and a group of companions and they’d be lost, both physically and metaphysically…

“Old Westerners like their jeeps and their ATVs…one thing they’d rather not do is be seen agreeing with an environmentalist.” (Brave New West, 2007, p. 231).

I suspect that to a significant degree both the copper miners of Nevada and the coal miners of West Virginia are like the Old Westerners Stiles describes.

And to them both, as he indicates, environmentalists are anathema. Here in West Virginia, over the years, I’ve repeatedly seen the following cartoon decal on the back window of pick-up trucks that also sport coal miner symbolism: a little boy looks backward with a prankster’s grin, joyfully peeing in a symmetrical arch upon the words “Tree Hugger.” Now I don’t know if, in driving around Ely or walking through Ruth, I’d find that decal but I don’t think I’d have any trouble finding that sentiment. To miners the priorities of environmentalists are an ongoing threat to their capacity to make a good living.

That said, now for the experience of solitude. Here in West Virginia, notwithstanding the numerous bombed-out wastelands we euphemistically call mountaintop removal coal mines, the landscape retains its overall loveliness. For three reasons: its near-universal hilliness has made hacking away the thick carpets of deciduous trees for farming untenable, the anemic economy continues to dampen population growth, and our state remains free of huge, metastasizing cities.

So West Virginians still connect to this land, emotionally if not spiritually. Here’s how I know. A useful technique in doing hypnosis is visualization: for example, simply asking your client to picture a relaxing scene and then tell you what it is so you can use it in hypnosis in the future. In most cases my clients have picked either being out in the woods or walking on the beach (Myrtle Beach, South Carolina, is a favored vacation spot in these parts). Also, I’ve found that merely talking with many clients, particularly male clients, about hunting or fishing is deeply relaxing for them. Not about shooting at an animal or hooking a fish per se: simply about being deep in the woods or out on a still lake. They connect with something out there. And here is the thing: over many years I’ve seen no indication that this phenomenon excludes coal miners.

While solitude is discernable to a degree in West Virginia thanks to certain favorable conditions, it is vast and overwhelming out in the Great Basin Desert of central Nevada, provided that a person’s heart is open. It’s that long, long, long open horizon, stretching into the cosmic west from that little road running in front of Ruth, Nevada, and that gigantic copper mine. From right there Gail and I and the bikers could look out and see that harsh, infinite desert space that reveals infinity. And I’m pretty sure that at least some of those miners, after a rugged shift, stand in that very place and see that revealed, to their delight.

While others lean back and fart a good popper while envisioning a pay check.

***

That afternoon, 121 miles further west along U.S. 50, Gail and I found the BLM’s run-down Hickison Petroglyph site at 6,500 feet in an attractive draw. A rock outcrop at the western edge offers a handsome view of the Smoky Valley and the long line of the Toiyabe Range, with peaks running over 11,000 feet.

According to an old, scanned-in brochure I located on the internet the petroglyphs, extensively carved into tall rock faces, are ancient. I don’t know if this was a sacred place to the people who made those elaborate carvings, but it sure has that feel. They must have sat together in twos and threes on that very rock outcrop where I sat, gazing across that same empty expanse of land, past the wide tan plateau beneath me and the long tan Smoky Valley, at the ethereal blues and dark browns of the symmetrical mountains. As silent and empty on the day we were there as it was way back then.

According to an old, scanned-in brochure I located on the internet the petroglyphs, extensively carved into tall rock faces, are ancient. I don’t know if this was a sacred place to the people who made those elaborate carvings, but it sure has that feel. They must have sat together in twos and threes on that very rock outcrop where I sat, gazing across that same empty expanse of land, past the wide tan plateau beneath me and the long tan Smoky Valley, at the ethereal blues and dark browns of the symmetrical mountains. As silent and empty on the day we were there as it was way back then.

While I confess a tendency to romanticize the hunter-gatherer-way of life, I try to compensate by plodding toward a balanced view. So let me acknowledge here that compared to our historically comfortable existences of today, hunter-gatherer life was in many respects nasty and rugged, with a lot of deaths in childbirth and high infant and child mortality, that most people didn’t live very long in any case, that sometimes old and infirm people got left behind to starve, and that males in particular often died of trauma related to hunting and sometimes warfare.

Even so, hunter-gatherer life was the fundamental environment of our evolutionary adaptation and although seemingly remote from our ways today, remains our most fundamental biological if not psychological frame of reference. If a time machine could somehow beam us back there long enough to get past the shock of life with no toilets, movies, or restaurants, if we could keep an open mind after losing all that, I believe we would begin to have odd feelings of familiarity and connection.

One of these being a strange joyfulness at sitting silently for hours on end on that rock outcrop with one or two people we’ve known and cared about for a lifetime, with no schedule or watches barking at us. With an utter completeness that we would discover had always been within us, but that we had barely glimpsed in our harried, civilized lives.

In other words, we would experience the healing of a searing emotional wound that we’ve repressed to such an extent that we’ve forgotten it’s there. I mean our dissociation from the landscape, from what I call the wildness of the land. I believe that to one degree or another, this dissociation haunts modern people. Suppressing it, which our consumer culture does everything it can to aid and abet, protects us from the anguish of realizing that even as we try to enjoy our landscapes and ecosystems we’re progressively tearing them apart in manifold ways.

Yet thus far the cultural imperative is maximizing profits and prosperity, no matter what.

SCOTT THOMPSON is a regular contributor to the Zephyr.

He lives in Beckley, WV.

To read the PDF version of this article, click here.

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

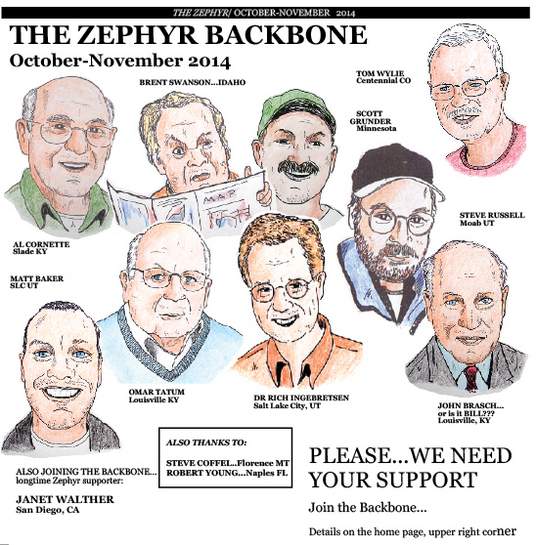

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!