“We might expect a peculiar change in the mentality of the world in the next fifty to one hundred years.”

– Carl Jung, 1929

I believe that Jack Burns, a character in several of Edward Abbey’s novels, is in effect a time traveler from the pre-agricultural world. The hunter-gatherer societies that inhabited that world thrived for nearly 200,000 years and constituted the basic environment of human evolutionary adaptation. In duration they dwarf the last 5,000 years of agriculture-based human civilization (“syphilization” is what Ed called it).

I also believe that humanity is destined to reclaim salient features of those pre-agricultural societies, whether we do so by our own choice or because we are hammered into it by a long series of ecological disasters.

So Jack Burns is also a time traveler from humanity’s future.

He first appeared in Abbey’s 1956 novel, The Brave Cowboy: “He was a young man, not more than thirty. His neck was long, scrawny, with a sharp adamsapple and corded muscles; his nose, protruding from under the decayed brim of the [cowboy] hat, was thin, red, aquiline and asymmetrical, like the broken beak of a falcon. He had a small mouth with dry lips, and a chin pointed like a spade, and his skin, bristling with a week’s growth of black whiskers had the texture of cholla and the hue of an old gunstock.” (p.6.)

In the novel Burns rode his temperamental mare Whiskey into Duke City, New Mexico, in order to rescue his close friend Paul Bondi from jail; where he was sent for refusing to register for the draft. Burns engineered his own arrest in order to help Paul break out, but his friend had already decided to serve out his sentence. Burns then escaped on his own and outran the Sheriff and his deputies on a local mountain range, only to be crushed by a tractor-trailer loaded with privies when Whiskey panicked crossing a highway at night.

Abbey’s 1980 futuristic western Good News was set in Phoenix following the collapse of the dominant political system. Burns was a one-eyed old man, once again on a rescue mission. He and his Hopi friend Sam Banyaca rode into the smoldering ruins of the city to find Burns’ son, an officer in the army of a local tyrant who sought to re-establish a mass hierarchical social order. Burns failed to persuade his son to leave and was promptly shot down in an impulsive attempt to kill the tyrant, once his son had refused. Oddly, Burns’ body vanished before the tyrant’s soldiers could bury it.

So: two novels, two rescue attempts, two failures. And Burns was killed, or apparently so, both times.

Usually, that doesn’t make for a memorable character.

Yet there was something about Burns that was strangely appealing and also disquieting: for example, the way Jerry Bondi, Paul’s wife in The Brave Cowboy, reacted to him: “She was having trouble with her thoughts; this man Burns, whose mere physical presence was so reassuring, and whose love and loyalty she could never have doubted, yet made her feel for some reason a shade uncomfortable: in his sombre eyes, in his slow smile and the lines of his face, in the firm rank masculinity of his body, she thought she perceived a challenge. A challenge in his every word, every motion.” (p. 30.)

Perhaps she had such a pronounced reaction to him because he possessed ancient human qualities that rang true on an intuitive level, but that threatened to demolish her social conditioning. Qualities that contemporary urban literary critics (“literary crickets” is what Ed called them) were much too dense to fathom.

I’d like to discuss some of these qualities.

Burns was striking in that he had no emotional connection to the abstract notions and institutions of the mass culture that surrounded him. It was not that he was disloyal to them, strictly speaking: he was not a card-carrying rebel or revolutionary. Such institutions were simply irrelevant to him.

Several examples from The Brave Cowboy stand out. Let’s begin with a conversation between Burns and a police booking officer following his arrest for a fight in a local bar:

“‘What’s your address?’ said the booking officer.

‘I don’t have none,’ Burns mumbled hoarsely.

‘You got to have an address.’

‘I don’t. I just wander around wherever I feel like.’

…

‘What’s your occupation?’ asked the booking officer.

Burns looked at him. ‘Cowhand,’ he said; ‘sheepherder; game poacher.’

‘Which is it?’

‘All of them. What difference does it make?’

The booking officer typed for a minute. ‘Where’s your papers?’ he said.

‘My what?’

‘Your I.D. – draft card, social security, driver’s license.’

‘Don’t have none. Don’t need none. I already know who I am.’” (pp.71-72.)

Imagine what it would feel like to shred every card you have in your wallet: credit cards, voter registration card, library card, driver’s license, social security card, professional membership cards, and so on. Imagine how doing that would affect your way of life and how it could alter your subconscious picture of who you are.

I’ve had dreams myself about beginning to accomplish something important and then losing my wallet and going into a panic. Our collectively defined identity has a powerful grip on us.

Here is a dialogue in the jail between Burns and his compadre Paul Bondi:

Bondi: “‘…I composed a little pledge or prayer…Would you like to hear it?’

‘Yes,’ Burns said.

‘It went like this: “I shall never sacrifice a friend to an ideal. I shall never desert a friend to save an institution…Great nations may fall in ruin before I shall sell a friend to preserve them…”’.

…

‘I’ll not argue it,’ Burns said; ‘I like it; I think I thought of it before you.’” (p. 109.)

Group size matters. I suspect that when an organization is large enough to start issuing membership cards, that’s when – strangely – it’s at risk of selling out its own members.

Such behavior by large groups is unfortunately commonplace, and that may be a reason why mass societies are filled with disillusioned people, and also why their institutions are plagued by chronic public mistrust. Examples: (1) an ethical employee reports misconduct within a corporation or non-profit agency and is fired and scapegoated in order to protect the organization’s public image; (2) a professional organization undermines its own objectivity by taking huge sums of money from pharmaceutical companies, despite the earnest protests of its more alert members; (3) legislators who are supposed to represent the public’s best interests consistently give priority to the demands of lobbyists for multinational corporations that finance their election campaigns.

By contrast, pre-agricultural societies were comprised of small bands, typically made up of only a few families. It has taken me a long time to appreciate how resilient and emotionally healthy such a seemingly frail social framework is. This is because the well-being of an individual member of the group is much more likely to be congruent with the well-being of the group itself, and because the leaders are less apt to be emotionally distant, hierarchical figures. So that the people are far more likely to trust them. Deeply. That is the key.

Burns seemed to know this.

The following scene from The Brave Cowboy is relevant to dealing with these organizations:

“When the arroyo turned he rode up out of it and across the lava rock again, through scattered patches of rabbitbrush and tumbleweed, until he came eventually to a barbed-wire fence, gleaming new wire stretched with vibrant tautness between steel stakes driven into the sand and rock, reinforced between stakes with wire staves. The man [Burns] looked for a gate but could see only the fence itself extended north and south to a pair of vanishing points, an unbroken thin stiff line of geometric exactitude scored with a bizarre, mechanical precision over the face of the rolling earth. He dismounted, taking a pair of fencing pliers from one of the saddlebags, and pushed his way through banked-up tumbleweeds to the fence. He cut the wire – the twisted steel resisting the bite of his pliers for a moment, then yielding with a soft sudden grunt to spring apart in coiled tension, touching the ground only lightly with its barbed points – and returned to the mare, remounted, and rode through the opening, followed by a few stirring tumbleweeds.” (pp. 11-12.)

To me, cutting the rigid extension of barbed wire is a metaphor for severing our emotional ties to the self-serving, sometimes self-destructive, norms and proclivities of large, collective organizations (as opposed to violating property rights in a literal sense).

I think it’s significant that in this scene Burns pulled out his fencing pliers only after he’d tried to find a gate. This suggests that he was willing to function within the structure of mass systems as long as he could pursue his way of life: as he put it, to “wander around wherever I feel like.”

But for each of us, as was the case for Abbey himself, the moment of conflict arrives when the expansion of the system’s functioning closes off all the gates, and when obeisance to that system means that something inside us will die.

What then? Our culture only offers its beaded string of threats: don’t make waves, don’t bite the hand that feeds you, you gotta go along to get along, don’t be a trouble maker. But if we do give in a lassitude begins to work its way through us like a fungus. The movie version, Lonely are the Brave, aptly depicts the result: the Sheriff pursuing Burns has a visceral contempt for his own compliant, lazy deputies, while admiring Burn’s boldness – in spite of himself.

But what does cutting through the expanse of barbed wire mean if it isn’t just simple-minded defiance? What else is involved?

A peculiar clue comes from the following conversation between Burns and his amigo Sam Banyaca toward the end of the novel Good News:

Banyaca: “‘…Listen, boss, I learned one thing at Harvard. There’s one thing wrong with always fighting for freedom, and justice, and decency. And so forth.’

Burns looks up at the blazing sky. ‘Only one thing? What’s that?’

‘You almost always lose.’

The old man laughs, reaches out, and squeezes Sam’s near arm. ‘Well, hellfire, Sam, what does that have to do with it?’” (p. 222.)

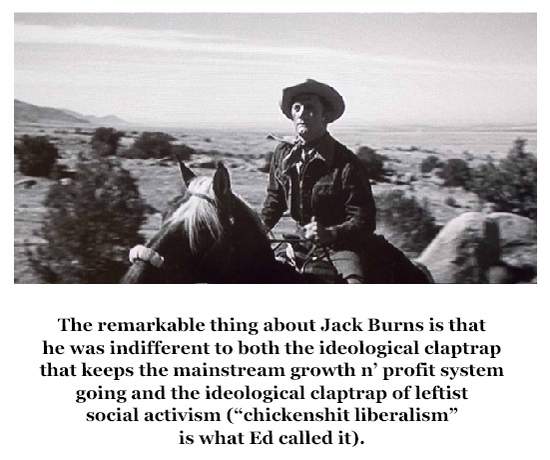

The remarkable thing about Jack Burns is that he was indifferent to both the ideological claptrap that keeps the mainstream growth n’ profit system going and the ideological claptrap of leftist social activism (“chickenshit liberalism” is what Ed called it). Which also refuses to see the big picture.

Put another way, there’s a canyon between doing what one can to change the system and expecting to get results on some kind of focused schedule. As a pre-agricultural person, Burns was all about the former and had virtually no concern about the latter.

This is a key point. Pre-agricultural humans were not liberal activists; the difference is that liberal activists can be as impatient to enact their social agendas as corporate CEOs are to jack up their quarterly profits. When we contrast the worldview of hunter-gatherer societies to that of our own culture, we see that the thinking of our liberals and conservatives is much closer than we usually imagine. Compared to either of them, hunter-gatherers might as well have been living in another solar system.

Briefly, here’s why. When our forbears became farmers, they got enmeshed in time lines: that is, when the rains were due, when to plant the crops, when to harvest them, and so on. And later on with market prices. In industrial and technological societies, this has escalated into a bizarre fixation on numbers and clock time: on productivity, quarterly profits, and election cycles. Time is money and results are everything. People living in this box are obsessed with short-term accomplishments and can’t see outside the lid.

Conversely, pre-agricultural people had no concern about measuring time. They were not in a hurry, because their universe was a timeless now. For that reason seeing a thousand years in a glance was a simple matter for them. They would marvel at our inability to do it.

In such a glance the first thing that becomes apparent is that our massively expanding economic system, as presently constituted, is absurdly unworkable; that it’s as ephemeral as a thunderstorm. The thought of taking such a system seriously would make them shake their heads or burst into laughter.

The danger of our gotta-get-it-done tradition of social activism is that the flip side is despair. We’re tempted to give up or compromise when we can’t identify a near-time causal sequence that will give us satisfactory results. That’s one of the prices we pay for our obsessive time-consciousness. No wonder when Sam raised the issue of losing, Jack Burns said, “Well, hellfire, Sam, what does that have to do with it?” Giving up or compromising weren’t options for Burns because they weren’t in his paradigm.

When we consider the approaching global warming fiasco, as well as the organized disinformation campaigns and public denial it’s generated, Jack Burns may be a useful figure to contemplate. This is because of his willingness to persist against superior odds and in the midst of seemingly hopeless situations that shut down many a devoted activist. What made Burns’ persistence possible, his secret in today’s terms, was his cheerful indifference to results.

Burns’ activist-like behaviors, if we can even use that term, did not arise from a commitment or some personal objective. It was primordial compared to that: he was simply living in the way that he enjoyed, and was willing to be killed in order to continue living that way. That abandon was what gave the man power, and was also what made liberal but conventionally-minded people like Jerry Bondi uncomfortable with him.

Have you noticed that when you’re damn straight enjoying yourself, clock time vanishes? That’s when there’s a glimmer of the pre-agricultural world. We also get fleeting glimpses of it through comedy, which utilizes absurdity like a blowtorch to reveal the truth.

Jack Burns showed us how to cut through the barbed wire – which is our own discouragement and the temptation to compromise – and keep on riding.

SCOTT THOMPSON is a regular contributor to the Zephyr.

He lives in Beckley, WV.

To read the PDF version of this article, click here.

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

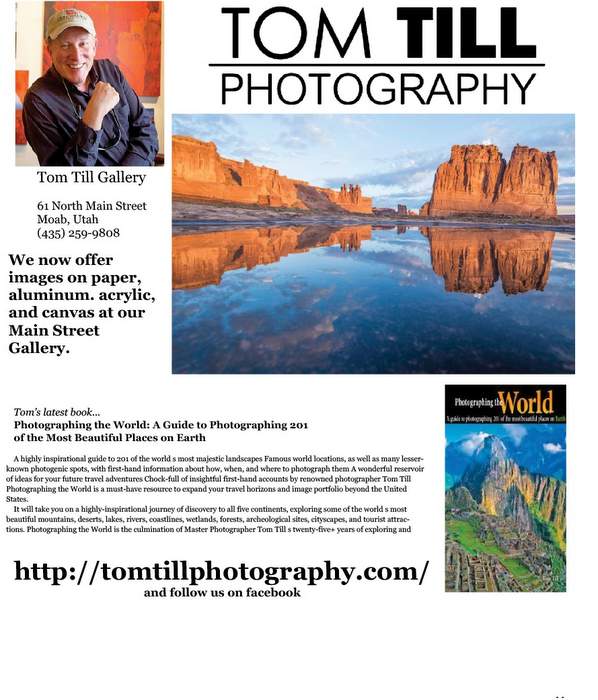

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!