A photograph is effective when the chosen moment which it records contains a quantum of truth which is generally applicable, which is as revealing about what is absent from the photograph as about what is present in it.

-From “Understanding a Photograph,” an essay by John Berger

I had not seen red rocks or canyons prior to my family’s move to Moab. I am not confident I had ever heard of them, either of red rocks or of canyons. What little experience I’d had in the west before coming to Moab was spent with an uncle in southwest Colorado. We didn’t look at canyons, my uncle and I. Instead, we went fishing.

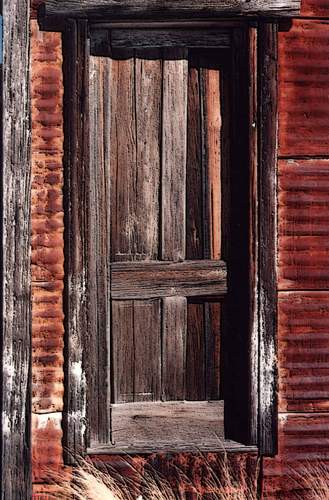

Uncle Lloyd took me fishing on a creek above a ghost town in the San Juan Mountains. He did not take me fishing above a village or an undiscovered community. He took me fishing above a town of ruins, of remnants, of no people. The dilapidated sheds and buildings sat quiet in the little valley, keeping the peculiar silence of a place abandoned. Old blankets, all of them dusty and stained, stayed on the few iron beds still in the cabins. Drinking glasses and deer mounts were left hanging in what had been a saloon. The place was quiet. The place was full of ghosts. Today the same village and its managers remind us, pathetically, that they are a resort, fitted with the now commonplace billings of “luxury,” “partnerships and rewards” and “highlights.” But, as mentioned, Uncle Lloyd and I went fishing. We caught cutthroat trout and later we returned to the ghost town and flipped through stained calendars of Charles Russell paintings and anonymous sketches of buffalo.

All landscapes invite a way of looking. The red rock country and canyons near Moab invited me, as a boy, to look up and to see a world that was in every sense above my head. The country appeared vast and splendid and in a way, impossible. I was entranced, naturally, by the landscape, which for a boy can extend beyond country and into his imagination. So for me, then, there were wise old men and horses and hermit huts somewhere in the rocks. Jeremiah Johnson was indeed up there still. And I wanted to climb the Moab rim.

From the valley to the top of the rim seemed far. For a boy coming from the flatland of East Texas, the distance from our house in the north end of the valley to the top of the rim seemed like a miracle requiring another miracle to cover so much ground. We had been just two weeks in town when I tried to hike the rim. I remember the day of the walk as being a Saturday and hot, even though we were not long into September. I blistered my feet. I didn’t bring enough water. I didn’t reach the top. I even lost a pocketknife my father had given me as a present. I don’t remember why I had taken the knife out of my pocket. I know I set it on a boulder when I did. Probably I picked or scraped at something, maybe at a twig or plant, or maybe I tried to sharpen the blade on a boulder.

I did manage to walk halfway to the top. These days I prefer to believe I reached a sort of middle country, with tremendous domes of Navajo sandstone overhead and the Moab valley below where I sat. I could see the sloughs. There were no houses there. Orchards grew in separate parts of the valley. I could see what people called Johnson’s Mesa. There were no developments, no progress to speak of. I could see bright crops of alfalfa pressed against the rim to the southeast of the valley. Then below me was the start of Cane Creek road. I cannot recall a sign informing me that the road was called Cane Creek. That was something I had to learn from locals. But all that country was going out and above me, and I was sure of their permanence then.

Perhaps I cannot escape the sentiment of my own experience. Such a point may be obvious, but there are particular angles contained in our moments of looking and seeing. Those angles shape our comprehension. They also reveal things that are true. In other words, we are not necessarily blinded by what we prefer. Some things, in fact, are and some things are not anymore. However, to value one thing over another becomes the stickier ground—both literally and metaphorically. Yet the ground is there to walk on, to become informed about and then to decide where we might go, if anywhere, and why. Admittedly our steps into a future can be humdrum, but why do we accept circumstances so casually in which we are told our routes are a given or already determined? That’s like eating shitty food over and over again and deciding there’s nothing else to eat.

Where I went thirty years ago was halfway up the Moab rim. I was dehydrated, captured by the view. I wondered where I had lost my pocketknife and how long it took someone, on average, to die of thirst. Probably my father was in town, I thought, sharing a cup of coffee with a priest. Yet I survived, obviously. I even tried to hike the rim again the following spring. I took the same way for no reason other than it was the way I remembered. Then I found my pocketknife. The knife was precisely on the same rock where I had stopped in September— untouched and unscathed. Still, I wiped off the blade. Then I went on again.

Damon Falke’s most recent work, Now at the Uncertain Hour, received a grant from the New York

Council on the Humanities and subsequent performance in upstate New York. His work has appeared

on the Reflections West radio program and in numerous literary journals. His recent novella, By Way

of Passing, is published by Shechem Press. He lives abroad.

All article photos by Jim Stiles.

To read the PDF version of this article, click here.

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!