I had taken many trips down the Colorado River through Glen Canyon, and I found many priceless experiences. But as 1963 approached, at 34 years of age, the dam’s effects thrust my mind into an upsetting quandary.

That year the reservoir rose at such a rapid rate. God-given treasures faced destruction each day. The reservoir flooded and destroyed many beautiful side canyons and grottos, thousands of ancient Indian ruins and writings, and even the majestic Music Temple and Hidden Passage. For a brief spell, previously, I thought of escaping north to the peaceful and quiet country of the Yukon.

But on one night in 1963 as I camped on the river sands at the mouth of the Escalante River, I concluded that I needed to continue to be close to the land I treasured in spite of the dam. But how? And suddenly it came to me. What a great thought! Why didn’t I think of it sooner! During that entire trip, the thought developed and expanded. It was this: I’d move my family and myself to one of the most out-of-the-way spots in Utah. I returned home and told my wife Marilyn that we were moving to Escalante!

But on one night in 1963 as I camped on the river sands at the mouth of the Escalante River, I concluded that I needed to continue to be close to the land I treasured in spite of the dam. But how? And suddenly it came to me. What a great thought! Why didn’t I think of it sooner! During that entire trip, the thought developed and expanded. It was this: I’d move my family and myself to one of the most out-of-the-way spots in Utah. I returned home and told my wife Marilyn that we were moving to Escalante!

So I turned my attention in 1963 to Escalante and its incredible river canyons. Those years were critical pivotal years for me. Now some 39 years later, I often reflect back to those times and places. I moved to Escalante to take trips, explore the canyons and to raise my family. I rented an old 1917 white-frame house, a block off Main Street. My family followed the following year after school ended.

Only about 700 or so people lived in Escalante. The main street held most of the local businesses, and beautiful green alfalfa fields abutted it at both ends. The land and the small farms sloped down to one of the streams that form the Escalante River.

The town was settled in 1875, a mere 54 years before my own birth. Most of the colonizers came from either Panguitch or Parowan. Some of my ancestors planted their cultural roots in Escalante too. These included the extended families of some of the Spencer, Lee, Griffin, and Allen families. Great granddad John Miles taught early school in Escalante, and my grandmother fondly remembered her days there. My great, great grandmother Emily Bush Spencer, after becoming widowed, came to the area and she was buried in Cannonville, but I’ve failed to find her gravesite.

The town was settled in 1875, a mere 54 years before my own birth. Most of the colonizers came from either Panguitch or Parowan. Some of my ancestors planted their cultural roots in Escalante too. These included the extended families of some of the Spencer, Lee, Griffin, and Allen families. Great granddad John Miles taught early school in Escalante, and my grandmother fondly remembered her days there. My great, great grandmother Emily Bush Spencer, after becoming widowed, came to the area and she was buried in Cannonville, but I’ve failed to find her gravesite.

Escalante still struggled as a very young village when the legendary Hole-in-the-Rock colonizing party passed through in 1879 on its way to the San Juan River country. The large party, some of its members my own distant relatives, made the trip in six months, a trip they thought would last only six weeks. My mind’s eye sees them cuttin’ up at Dance Hall Rock. For all the trip’s warts and faults, it surely wound up as a good faith-promoting story.

Robert and Louise Liston, my neighbors, lived just across the street. Robert was a real cowboy while Louise was a friendly and talented teacher who later transformed herself into a prominent and outspoken county commissioner. And down the street, my friends John and Lola Zenz owned a lapidary shop. They cut and sawed pieces of local petrified wood into striking shapes and multi-colored table tops and sold them to admirers and to tourists. Though nearly blind, John did marvelous work.

I spent a lot of time at cousin Mohr Christensen’s Moqui Motel. My clients met there and at the other rustic-looking motels in Escalante when coming on trips. Mohr later became the mayor of the town.

When not down in the canyons, I’d stroll down daily to Whitey’s Café. A few of us formed our own little cluster and a table always awaited us. I claimed a favored seat, as I liked to sit facing the entrance door checking out all who entered. (I could then either greet the person or take evasive or protective action.)

Some old-timers and we newcomers joined together to help solve the town’s economic problems. From it, we organized a Chamber of Commerce and I became its first president. However, Ray Fynan pretty much kept the thing going. She was an accomplished woman with ideas—energetic and sometimes aggressive but quite good-looking. We held our meetings at the old school house. Before long, we recruited some 26 members or so. Because of our town-meeting format, additional townsfolk drifted in from time to time. We made known the issues to be discussed before hand, and this proved quite successful.

It was a sort of a debating society, and I’ve had occasional spats with the local people over the years. Friends and neighbors often do that in a small town, and as long we all had an active part in the community we could talk our differences out. This provided a great forum. Members dedicated many hours to the cause. For instance, we compiled and printed the town’s rules and ordinances. We helped to find a competent and dedicated doctor in the person of Dr. Kazan of Page. He flew his own plane to Escalante to care for our people a couple of days a week. Tragically, he was killed when his plane crashed into a cliff face of the Kaiparowits on one of his flights to Escalante.

We campaigned for a safer Escalante-Boulder road, a dangerous and narrow roadway linking the two towns. The road served the transport of Boulder school children to Escalante. There was no dispute here, and soon the road received more funding and better improvements. We did argue about other roads, particularly the Boulder Mountain route to Wayne County. I disputed the need for paving it, but Nethella Woolsey, our road committee chairman and former legislator, worked hard to secure the funding for it. I felt an all-weather route, the Burr Trail, would have been better. I soon reversed my reasoning and opposed the Burr Trail route when the Boulder Mountain route became a reality. We only needed one road, I thought.

We talked a lot about tourism, thinking that it would bring in much needed income. So we researched the ways and means of making the Boulder highway a “national parkway,” patterned after the Blue Ridge Parkway.

We strived to improve the look of our town. I was chagrined when Nethella also campaigned to remove old broken-down barns, and this issue elicited some debate at our Chamber meeting. The installation of aluminum siding on many old homes resulted from past efforts.

And Nethella often chastised the citizenry when they’d call the town’s name “Escalant.” Kind of a lazy hick-town sound, she said. Historian bent, she compiled and published her book The Escalante Story, a history of the community from the time of its settlement in 1875 to 1964. She included many unsmiling and stern portraits of the old timers—many of them having that pioneerish and hardened look. My cousin Jared Porter’s picture could scare the bejeeze out of anyone.

I spent much of my time in the canyons, but I frequented Coyote Gulch more than any other canyon. It includes Jacob Hamblin and Coyote natural bridges, and Jug Handle Arch. I suppose Jacob deserves his name on some feature here. As a Mormon missionary and scout he traveled to Escalante country even before its settlement. He intended to take needed supplies to John Wesley Powell’s river party at the mouth of the Dirty Devil River. But he goofed as he mistook the Escalante for the Dirty Devil River. Battling the quicksand, his packers moved slowly down the Escalante, about 50 miles it is said. Exhausted and dismayed, the party quit and returned to Kanab.

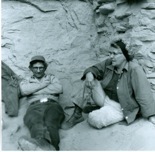

Negotiating this country often comes hard. Going down Coyote Gulch on one trip, a giant part of the wall broke away and tumbled into the creek bottom below forming a natural dam. My old intrepid friend Vaughn Short helped me fashion a detour around the slide, and I hammered a few indents into the sandstone to get our horses and mules around the long pool of water.

Vaughn helped me on many other trips and occasions also. Once on a winter trip, the two of us hiked down Coyote in the snow and in twenty-below temperature. God it was cold! At night, we’d pile a bunch of wood next to us so that we’d merely have to reach our arms out to throw a stick onto the fire. Vaughn was the hero as he kept the fires blazing as I dug deeper into my sack.

One day rancher Reeves Barker came to my office and asked to be considered for a wrangling job. It was obvious I needed good hands so I immediately hired him and he soon became my head wrangler. Another cowboy, Mac LaFevre, from a ranch near Boulder also admirably fit the bill. I hired others when I needed them. Not only did I hire local men, I leased their horses and mules, and they would often supply their own trucks to haul them. And Lloyd Gates continually helped me in arranging and acquiring pack stock. His son Lynn operated the local gas station and garage and helped me keep my small Ford pickup in the best possible shape.

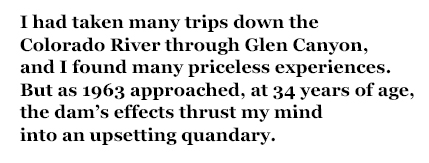

I knew the lower Escalante River canyon quite well as I had explored much of it by repeated hikes from the boats. Clear Creek and the Cathedral-in-the-Desert proved popular and enchanting destinations. I remember my first time there. In parting the branches of the willows that stood at its entrance, I took a look inside. I was astounded, just astounded and yet so dismayed. I knew that the reservoir would soon destroy this most enchanting temple.

There were many canyons to explore. Gregory Natural Bridge became a destination site. Heartbreaking it was to later see the reservoir completely close the opening of the Bridge and then to cover it completely.

We often visited the wondrous Broken Bow Arch in Willow Gulch. My old friend and trip canyoneer, the  indefatigable Edna Fridley, kept returning with me, as it was one of her favorite canyons. Downstream below Broken Bow we’d hike and climb into the narrow confines of 40-mile creek, sometimes referred to by the descriptive but unsuitable characteristic—slot canyon. Why not slit canyon, or slut canyon?

indefatigable Edna Fridley, kept returning with me, as it was one of her favorite canyons. Downstream below Broken Bow we’d hike and climb into the narrow confines of 40-mile creek, sometimes referred to by the descriptive but unsuitable characteristic—slot canyon. Why not slit canyon, or slut canyon?

When I first went overland into Davis Gulch, Lloyd Gates drew me a crude map. With pencil in his hand, he directed me to a point on a mesa where the stock trail quickly dropped into the canyon. He would pronounce a mesa—“may-see.” Damned if I didn’t pick the expression up too. The longer I lived among the Escalantans the more I talked like them, a decided improvement over my own local-yokel style.

Everett Ruess, the young wandering poet, branded Davis Gulch as a destination favorite merely because he ended up as a missing person there in 1934. He left his traces in the ruins and writings on the walls and so the “Everett Ruess Natural Window” becomes a testament to his memory. I delighted in guiding his brother Waldo there.

The desert road exhibited some danger spots. A river friend of mine, Merlin Shaw, took his group of scouts in an open truck along the road heading to the Hole-in-the-Rock. There they would hike down to the reservoir to meet their boats. But at Carcass Wash, the group met calamity as the driver lost control of the truck. The truck quickly rolled down backwards and overturned at the bottom of the canyon. Merlie and eleven others were killed and twenty five others injured.

Another unique trip I made during this period occurred on the Powell reservoir. As the waters rose higher, two of rancher McKay Bailey’s straggler-bulls still managed to survive on an isolated river bar that still stood above the reservoir’s surface. I met McKay at Jackass Bench and by boat we went down and killed and butchered those bulls. All night, in the cool air, we carried the cargo to Wahweap. For my part, I got half the salvaged meat, which we ground into hamburger.

One time I went with Reeves into the “Smokies” in the Kaiparowits area to help check and move his cattle. Hauling our two horses in his pickup, we ended up at his makeshift cabin. Reeves put together some great baking-soda biscuits, heavy with butter and raspberry jam, and we dug into them like they were going out of style. His good wife Laura had packed us some hams and cake to go along with them. After supper, we cleaned up our mess, and we spent the evening crouched near the fire telling glorious old yarns. Next day, we spent the day with the cattle, and he showed me a smoking “slot” where coal had been burning for years if not centuries.

I always enjoyed the wildness of Fifty Mile Mountain. My rancher friend Cecil Griffin had given me many pointers on this wild area. We followed a steep winding trail that required the best of horses. Once on top, we traveled from the Mudholes through the pines and out to the further point of the plateau where we could see for over a hundred miles into the canyon and mountain country of Arizona and New Mexico.

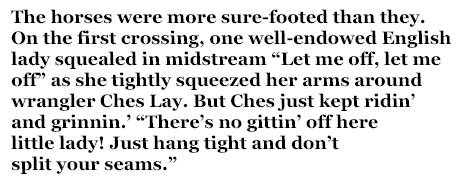

Reeves and five other wranglers joined me in taking a huge group of Sierra Clubbers down the Escalante. They hiked and did their own cooking. Our horses, 26 in all, carried their provisions, gear, food, pots and pans, bedrolls and tents. The rains had come down hard and sent a flood of rising water down canyon. During the day, Harry Aleson had boated the folk across the reservoir to Rainbow Bridge and back. On the return to camp, because of the higher water, we had to give each Clubber a ride at each river crossing on the back of our horses. The horses were more sure-footed than they. On the first crossing, one well-endowed English lady squealed in midstream “Let me off, let me off” as she tightly squeezed her arms around wrangler Ches Lay. But Ches just kept ridin’ and grinnin.’ “There’s no gittin’ off here little lady! Just hang tight and don’t split your seams.”

And speaking of the Sierra Club, I’ll never forget the valiant and hard work of two of their most able leaders, Ruth Frear and June Viavant. They helped stop the proposed Trans-Escalante highway that would have stretched from Bullfrog to Wahweap marina. The road would have bridged across the Escalante canyon just downstream from Stevens Arch and Coyote Gulch. This was one of the environmentalists’ finest hours in Utah.

A lot has happened to the small town of Escalante since I lived there. It has become amazingly easy to reach and people now want to go there because of the “National Monument” designation. It’s hardly a picture of the old west any more. Gone are those adventuress and good times and those peaceful and quiet times. This old duffer knows that they can never be brought back the way they once were.

But as Reeves would always say as we headed home, even though it was hotter than blazes, “It’s all down hill and shady from here on, Ken.”

Click Here to Read Ken Sleight Remembers, Part 4: The 60s, “Unscrewing the Locks.”

Click Here to Read Ken Sleight Remembers, Part 3: The Early 50s, War and the Longing for Red Rocks.

Click Here to Read Ken Sleight Remembers, Part 2: THE 1940’S: THE SHAPING OF A LIFE

Click Here to Read Ken Sleight Remembers: Part 1: The Adventure of New Beginnings…1930s.

To read the PDF version of this article, click here.

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!

I took a trip down the San Juan River in 1964 to put a plaque on Shaw’s Arch. Bishop Shaw was killed the year earlier in a truck rollover. I am trying to figure out where we put our boats in the river….I thought it was west of Mexican Hat. But, I went down in that area last year, and there is a motel/cafe now where I thought we launched our rubber rafts. I may have had the wrong location. Do you know that launch location?

[…] Sleight, K. (2015, June 1). Canyon Country Zephyr. Ken Sleight remembers, part 5: the 60s, “memories of Escalante.” Retrieved from: https://www.canyoncountryzephyr.com/2015/06/01/ken-sleight-remembers-part-5-the-60s-memories-of-esca… […]