From the Zephyr Archives…

In the 21st century, it is ludicrous…indeed, quite tragic, to have to defend the actions taken by Congress on August 25, 1916 when it established the National Park System. The American people purposely, in the creation of National Parks, aimed to set aside and to preserve areas of great primitive beauty and scenic grandeur, areas of inestimable aesthetic and recreational value. Each national park or monument has some particular central feature of outstanding beauty and interest, or some prominent theme. The outstanding feature of Rainbow Bridge National Monument in Glen Canyon was the wondrous bridge itself and the adjoining canyons and living rivers. They all were indeed unique to all the world.

The American people directed its agencies to preserve these hallowed areas to keep them unimpaired, and unspoiled, so far as is humanly possible, for the benefit and enjoyment of its citizens and for future generations. It has been a source of inspiration for us all.

For this very reason was the Rainbow Bridge National Monument in Glen Canyon created.

It is so hard for me to believe that after all these years, one federal agency, the Bureau of Reclamation actively solicited Congress to break that long-established policy by authorizing the impairment of the Monument by allowing a reservoir to intrude and destroy its sanctity.

In 1954, the Bureau, its supporters and its lobbyists, undermined the very concept of national parks. They argued, over and over again, that by flooding Glen Canyon and the Rainbow Bridge National Monument, in the very heart of Glen Canyon, this national treasure would actually be “improved.” They attempted to instill in the minds of the public that a substitute concept, designed to convince the unwary that the impoundment would furnish recreation for many people. They knew that by drowning these beautiful canyons, by obliterating entirely its outstanding living rivers, the area would no longer qualify as a true National Park and its usefulness as such would be gone. It would have lost the very purpose for which it was set aside. It would then be open for development.

In 1956, the Colorado River Storage Act was enacted, and soon a series of major dams and storage reservoirs drowned many of our rivers and beautiful canyons. Work started on the dam even before the protection of Rainbow Bridge National Monument was assured. By February 11, 1959, the cofferdam blocked the river.

Meanwhile, plans were made by the Bureau to build barrier dams in Forbidding or Bridge Canyon to keep the reservoir waters out of the Monument so as to not impair it. By 1960, President Eisenhower requested funds in his budget for the protective structures necessary, but Congress repeatedly refused to grant them. Senator Frank E. Moss of Utah even introduced a bill in Congress to strip the protective provisions of the law. The backing-up of the water would not impair it but would substantially enhance it, he said. His bill went nowhere, but the damage had been done.

So in the Bureau’s eyes, it was either hold the reservoir waters at the lower 3606′ level to keep the waters out of the monument, or build barrier dams to keep the reservoir waters out. It opted for the barrier dam studies.

The Bureau, it seems, had no real intentions of ever building the protective dams, even though it went through planning stages. By August 1959, a mammoth construction plan was proposed with costly road accesses. Each of them would have been environmentally catastrophic in themselves.

In August 1962, the National Parks Association, the Sierra Club, and other groups filed suit in the U.S. District Court in Washington D.C., seeking an injunction to prevent the closing of the gates at the dam until the protective works for the Monument were assured. As the groups could show no standing, the judge dismissed the suit.

It was a tough time for the environmental community. On January 21, 1963, Floyd Dominy announced plans for a series of hydroelectric dams downstream in Grand Canyon. In 1963, the Glen Canyon diversion tunnels were closed, and the reservoir began its destructive rise. The Bureau refused to revise its fill schedule, permitting the reservoir to begin producing power in January even before the barrier dam questions had been resolved.

On April 1, 1963, the reservoir reached an elevation of 3,234 feet (above sea level) at the mouth of Forbidding Canyon. Soon it entered the canyon. Then the sandbar that stretched across its mouth and upstream, where Harry Aleson and I often camped together disappeared. The reservoir waters rose higher and covered the natural pools of stream water in the canyon leading to Rainbow Bridge. Springs went under and the cottonwoods, willows, and wildflowers were buried.

On June 23, 1964, the waters of the reservoir reached the junction of Bridge and Forbidding Canyon and encroached into the Narrows and Bridge Canyon. Soon it would reach the boundary of the Monument itself. It was a critical time.

At this point, I moved my family to the town of Escalante to be closer to the canyons. Instead of my river boats, I climbed astride my horse to see the canyons, and when I couldn’t get my horse up the canyon, I’d walk or climb.

I feel bad that kids and grandkids everywhere will never have the opportunity I had to see and experience Glen Canyon.

The reservoir quickly rose in the Escalante River. Once, I tied my inflated boats to the willows on the reservoir’s shore. When I returned a few days later with a new group, the boats were half-drowned. Only the rear ends of them still showed. I pulled myself down into the water to untie the ropes, but they were so tight I ended up cutting them.

Another time, when I had left my rig to go out to Escalante to get another group, my three outboard motors and my tool kits were stolen by “Lake Foul” boaters. Because of it, we retraced our steps and hiked canyons not yet despoiled. After the trip, the intrepid Frank Wright came over and towed my boats out to Hall’s Crossing.

But most painful of all were the major environmental tragedies. The lower part of the Hole-in-the-Rock went under and the register-rock names were obliterated where some of my past kin had scratched their names on the wall face as they made their ill-directed trip to Bluff in 1879.

The reservoir covered over the enchantment of Music Temple, the narrow pool-filled meandering passageway of Hidden Passage, and other beautiful canyons.

Thosands of ancient Indian ruins and sites were covered over and destroyed.

Rainbow Bridge would soon be in danger, despite the laws written to protect it. It was feared the famed structure might fall into the canyons once water encroached under it. Floyd Dominy didn’t seem to care. He said, “In my opinion, water up under the Bridge would make it a more beautiful sight.”

And a chorus of voices from Bureau of Reclamation geologists maintained that the reservoir water would not harm the structural integrity of the Bridge and said that barrier dams weren’t needed after all.

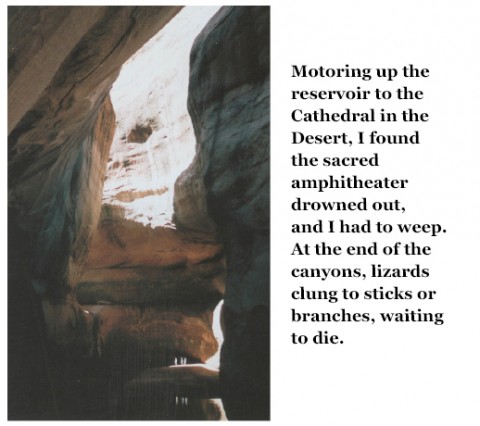

Motoring up the reservoir to the Cathedral in the Desert, I found the sacred amphitheater drowned out, and I had to weep. At the end of the canyons, lizards clung to sticks or branches, waiting to die. At the end of other canyons, I found dead carcasses of beaver, no longer able to harvest their cottonwood supply. Also, too, the massive Gregory Natural Bridge was devastated and covered over.

I made a deal with Barry Goldwater to use his Rainbow Lodge site near Navajo Mountain as a trailhead. It was my intent to hike my guists down the Escalante, then have Harry Aleson take them to Rainbow Bridge by boat, and then Navajo wranglers would meet and lead them around Navajo Mountain. Finally, Bill Wells, the Flying Bishop of Hanksville, would fly them back to Escalante. On my first trial run, I couldn’t even get my boats through the deep flood debris that had accumulated at the head of the reservoir in the Escalante. It was all a splendid idea, but a total failure.

Others were having their problems too. By 1969, Brower was dismissed from his job as Executive Director of the Sierra Club. He then founded the Friends of the Earth, and molded it into an effective activist group fighting to protect the Monument from reservoir waters.

By November 1, 1970, the reservoir had reached the 3,600 foot level and neared the lower boundary of the Monument. By coincidence or fate, I met Tom Turner and a party of the Friends of the Earth in Coyote Gulch. There, at Icicle Springs, after musing the topic over, I decided to be a litigant with them in order to help gain standing.

We’d sue the bastards.

And that month, according to plan, the Friends of the Earth, the Wasatch Mountain Club, and I filed suit in Federal Court to permanently enjoin the Secretary of the Interior from allowing the reservoir to rise above elevation 3,606 feet, so that it wouldn’t enter the Monument.

[Editor’s Note: For a year, in 1973, Ken and his friends had their victory. Chief Judge Willis W. Ritter ruled in favor of their injunction and halted the progress of the lake into the Rainbow Bridge Monument. Unfortunately, Judge Ritter’s ruling was overturned by the U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals and, when the Supreme Court refused the hear the case, the Bureau of Reclamation resumed the progress of the lake.]

In losing Rainbow Bridge, the Indian people lost a great heritage. Even today, they are involved in trying to keep the religious importance of the bridge at the forefront. Recently, the Mountain States Legal Foundation, the same folks who brought you the likes of James Watt, brought suit against the Park Service regarding this matter.

Rainbow was inspirational to me too. I often took my usual lying-down position under the bridge and listened again to the song of the canyon wren. I wondered if it was the same wren that sang to me on many other occasions. And I gazed at the clouds shaping themselves while moving high above the arch. The spring water dripped nearby under the ledge, and the redbud leaves shook in the soft breeze as I rested there. After my solitude, I’d lead my people to the top of Rainbow.

Author’s Note: And, with this, I urge you all to read river man Hank Hassell’s book, Rainbow Bridge, An Illustrated History. Also, I refer you to Russell Martin’s fine book, A Story that Stands Like a Dam. It was Martin who sat beside me and commiserated with me at one of my pathetic dam protests. And, of course, I highly recommend to you Edward Abbey’s The Monkey Wrench Gang. And, like Abbey, let’s all pray for that “precision earthquake.”

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE OF KEN SLEIGHT’S MEMORIES OF CANYON COUNTRY HISTORY

To read the PDF version of this article, click here.

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!

thanks for the history lesson ken, great to hear the front line perspective.