THANKS to Tom McCourt & the Tibbetts Family.

For years, I have been watching Moab move farther and farther away from its roots, to the point where it seems few people even know the history of the place anymore. Some of them don’t know OR care, but I think there are still many who have a respect for the past (I hope so, at least).

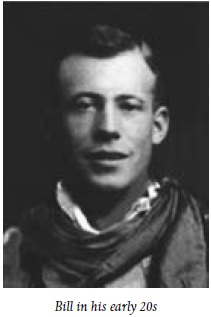

Last winter I read Tom McCourt’s book on Bill Tibbetts and think it’s his finest work. I knew a bit about Bill, but the story was told so beautifully and I felt it was a very moving tribute, not just to Bill, but to those far off times.

I see Moab as some alien world now, and I feel the most significant contribution I can make with the Zephyr these days, is to try and preserve the past in some fashion, or at least make it available for those readers who are interested. With Tom’s permission, the Canyonlands Natural History Association who published it, and with the good wishes and approval of Bill Tibbetts’ son Ray and the Tibbetts Family, we are pleased and honored to offer, over the next few months, excerpts from Tom’s excellent portrayal of ‘the Last Robbers Roost Outlaw.” JS

Chapter 3

The Widow’s Son

After the murder of her husband, Amy Tibbetts and her two small sons were alone on the ranch near old La Sal. Amy had family in Moab, but Moab was forty miles away over dirt roads and wooden wagon wheels. Some of her friends and family suggested that she move to town, but Amy wouldn’t do that. The little cabin in the wilderness was her home and she refused to leave it. She and Bill had dreamed of building a fine ranch there, with a beautiful home, and she wouldn’t let the dream die. Somehow, she would build that ranch with her sons and it would be a tribute to the life of the man she had loved so dearly.

Few people carried life insurance in those days, but Amy still had the land and the cattle to secure her future. She knew that if she left the ranch, her cattle would be scattered and the processes of nature would soon destroy her hard-won gains. Ditches required cleaning and fences needed mended. Also, if she moved to town, it was possible that some devious person might file a counter-claim on her land, insisting that she had abandoned the homestead. She had heard of such things happening to others. Amy was sure she could beat such a claim in court, but it might be a long and costly process and she wasn’t up to the fight. Better to stay and hold on to what she had.

But it was serious business to be a widow on the frontier, especially a widow with small children to care for. The demands of the cattle business required the full-time efforts of a good man. A woman with children just couldn’t do it alone.

Amy was making plans to enlist her brothers as partners when another cruel twist of fate intervened. She found that she was in debt. Her late husband had been charging goods at the general store in old La Sal, promising to settle up when his steers were marketed in the fall. It was a common practice. The store was owned by the Cross-H Cattle Company where Bill had worked as a seasonal employee.

And then, like a thunderbolt of bad luck, a cowboy she didn’t know came to her door with a note stating that her recently deceased husband owed him two hundred dollars. Two hundred dollars was a lot of money, most of a year’s wages for common folks. The man said that if she didn’t have the money he would be happy to take the land or the cattle to settle the debt. If not, he would see her in court.

Amy was convinced that the note was a forgery. Bill had never told her he was indebted to anyone. He was a man who prided himself on being self-reliant and she just couldn’t imagine him borrowing that much money from a cowboy and not a bank. Yet, in spite of her doubts, everyone agreed that the signature on the note looked like her late husband’s handwriting.

For months, Amy resisted desperately, but finally, disheartened, still mourning the loss of her husband, and with her spirit broken, she reluctantly signed the property over to the cowboy. She just didn’t have the heart to fight the man in court. Amy loved her ranch, but the more practical choice was to give up the land and keep the cows. The cows could provide an income for her and her sons and maybe the start for a new ranch. There was still land available for homesteading in the San Juan area, but it took years to build up a good herd of cattle. Amy cried when she signed her property away, but she knew she was making the right choice. She had to take care of her little boys.

Her suspicions about being cheated were reinforced when the new owner of her property quickly sold it to the Cross-H Ranch. The Cross-H had offered to buy the land from her late husband several times, but he had always refused. The Tibbetts Ranch was in a prime location with a good spring of water and a natural meadow that was perfect for livestock. Amy believed until her dying day that she had been swindled.

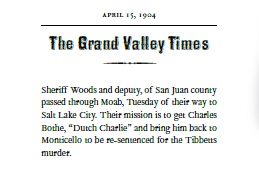

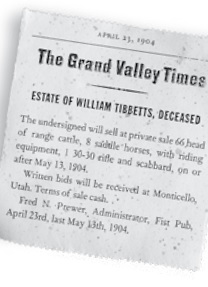

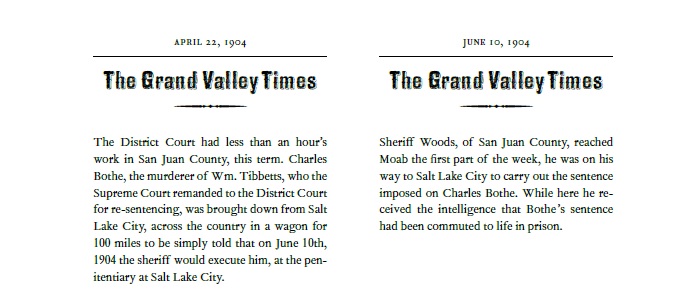

The young widow moved with her children to Moab, but had to sell off a good portion of her remaining assets to pay her debts and get settled in town. The following items appeared in the Moab newspaper in 1904.

Shortly after moving to Moab, Amy became reacquainted with an old friend from her school days. Wilford Wesley Allred, known as “Winny” to his friends, was two years younger than Amy, but he had been one of her suitors before she married the cowboy, Bill Tibbetts. Winny was still single and he stopped by often to visit and help with chores around her place. It wasn’t long before he and Amy were married.

Winny Allred was a good man, but much different from Amy’s first husband. He was a town person who  made his living as a musician. His family ran a few cows on the rangeland near Moab, but Winny was more at home wearing a silk necktie than a cowboy’s bandana.

made his living as a musician. His family ran a few cows on the rangeland near Moab, but Winny was more at home wearing a silk necktie than a cowboy’s bandana.

After Winny and Amy were married, the young man worked hard to provide for his family and make his new wife happy. He was devoted to her and always wanted her to have the best of everything.

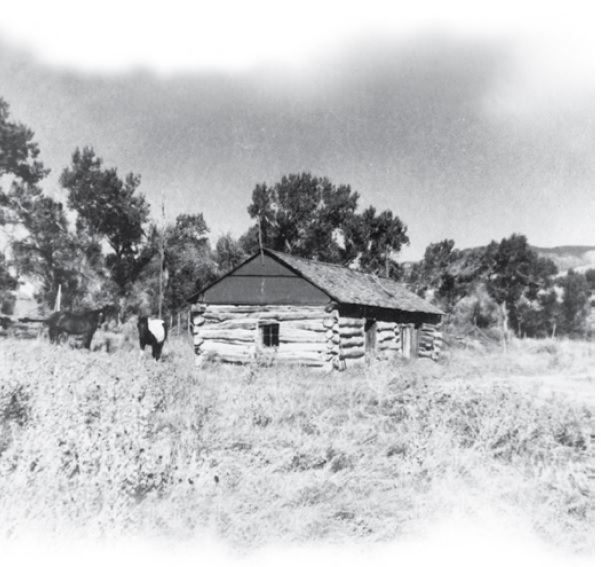

For a while, the new couple lived in Moab, but Amy grew restless living in town. Her heart was on the desert. She had been happy in her wilderness cabin at old La Sal and she longed for the red rocks and open spaces. She was a woman of strong will, and in spite of her new husband’s objections, Amy took her remaining cows and filed for a homestead in Brown’s Hole, on the west side of the La Sal Mountains, about twenty miles southeast of Moab. It was a good place to start a new ranch and a second chance to live her dream. With charm and firm resolve, she was able to win her new husband over and he helped her build a log cabin there. They planted a big garden and fruit trees. The family lived there for several years and ran their cattle in the foothills of the mountain.

The cabin at Brown’s Hole was very small in the early years, and with new babies arriving, there wasn’t enough room for everyone to have a bed. The older boys, the stepsons, Bill Jr. and his little brother Joe, had to sleep in a corncrib outside of the cabin at night. Big gaps in the walls of the shed-like structure allowed air to circulate and dry the corn.

Miles of wilderness surrounded the homestead, and the boys were terrified at night by the howls of coyotes and the shrieks of mountain lions not far from where they lay huddled. The big cats sounded like a woman screaming in the night. Navajos have called it the Moki scream, and they say it is made by the spirits of dead people who once lived in the cliff dwellings of the canyon country. To adults who have heard the sound, the experience is unnerving. To little boys, all alone in the dark, peeking out at the night through the gaps of a flimsy corn shed, the experience was a holy terror.

To please his new wife, Winny Allred went through the motions of being a cowboy and a farmer, but he wasn’t happy. His heart was still in town. He and Amy were not a good match when it came to setting up housekeeping in the wilderness. In spite of the homestead, the cows, and the demands of taming the frontier, Winny still tried to make his living as a musician. The job required that he spend a lot of time in town. He worked hard to be a good provider, but he was torn between the obligations to his family and the demands of his chosen profession. It was a conflict that would trouble his marriage, his family, and his life, for many years.

There were other problems in the family, too. For six-year-old Bill Tibbetts Jr., the marriage of his mother to a strange man was a distressing experience. The little boy wouldn’t accept it. He had fond memories of his father and he refused to acknowledge his mother’s new husband as anything but an interloper who threatened the sovereignty of what was left of his family.

As time progressed, the conflict between little Bill and his stepfather steadily grew worse. Bill was an active, impatient, and strong-willed little boy and he simply refused to accept this new guy as dad. Winny Allred was a strict disciplinarian and he was constantly at odds with the boy. Bill was spanked a lot. The beatings only deepened the boy’s hatred and resolve. Bill openly vowed that one day, when he was older, he would beat the hell out of his stepfather. The rivalry between the two became so intense that Amy finally sent little Bill to live with her parents in Moab. It was the only way to keep peace in the family.

And so, at the age of seven, Bill lost his mother to another man. He didn’t have a place in his mother’s new family. On top of witnessing the violent death of his father when he was only four, this new reality hit him like a hammer.

Bill remained committed to his mother, even though he didn’t get to see her very often after moving to Moab. The separation only increased his hatred for the man who had come between them. The little boy pouted and sulked.

At Moab, Bill’s grandparents, Joseph and Hanna Moore, became major influences in his young life. They owned a farm along the edge of town where they grew their own food and hand-made most of the items needed to sustain their lives. They were proud and independent people, and very religious. Joseph Moore had been a Mormon bishop in the town of Bennington, Idaho, in the 1870s.

Bill’s grandparents took him to church every Sunday and taught him all about right and wrong, the importance of being honest, and the value of keeping his word. They took him to Sunday School and read to him from the Bible and The Book of Mormon in the evenings. Shortly after his eighth birthday, they made sure that he was properly baptized, by immersion, in the cold and muddy water of the Colorado River.

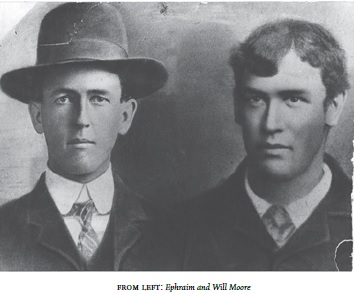

Young Bill got along much better with his grandfather than he did with his stepfather, and a couple of his uncles took the little boy under their wings and became adult role models, as well. Little Bill and his Uncle Ephraim Moore developed a special bond. It was Ephraim who had acted as midwife when Bill was born and the two became like brothers. It didn’t matter that Ephraim was eighteen years older.

But it was an older uncle, Will Moore, who became Bill’s father figure. Will was an old-time cowboy, strong, proud, and as tough as saddle leather. He reminded the little boy of his dad. Bill grew up idolizing his cowboy Uncle Will.

One of the advantages of living in town was going to school. Bill liked school and he became a good student, learning to read and write very well. He was interested in history, science, and literature. He read all of the books available to him at school and the home of his grandparents. Many of his grandparent’s books were religious texts, so the boy was no stranger to the stories of the Bible.

To get to school, Bill had to walk past the Jackson place. The Jackson boys were older and bigger than Bill, and the two of them would lie in wait for the skinny new kid and beat him up, almost every day. The older boys thought it was great sport and they carried it to extremes. Little Bill was terrorized by the bullying. He became afraid to go to school and afraid to go out to play. Finally, when the situation became obvious to the adults, Uncle Will took him aside for some intensive training in the manly arts of self-defense.

“It’s not the size of the man in the fight that counts,” the tough cowboy said. “It’s the size of the fight in the man. Those guys are bigger than you, but you can beat them if you set your mind to it. You can’t worry about being hurt. They’re going to hurt you anyway. You might as well attack and give some back. If you hurt them, they’ll learn to leave you alone. Here’s what to do the next time they start that stuff…”

It worked like a charm. Within just a few days, Bill had conquered the Jackson boys. He then beat up the big kid down the lane and a bully on the playground. His newfound assertiveness won him a lot of friends and a lot of attention at school. His self-confidence soared and he learned to swagger just a little. By the time he was ten, he had a reputation for being the toughest kid in school. Bill might have even gone a little too far when he discovered how easy it was to intimidate people. Over the next few years he tried every new kid in school, just so everyone would know who was boss.

Bill’s defiance of his stepfather, his constant fighting at school, and his need to be the top dog among his peers, might suggest that he had some deep emotional wounds to heal. The little boy had witnessed the murder of his father, the loss of his home, his mother’s new marriage to a man he despised, and the pain of being sent away from the family to live in a strange town with relatives. He surely felt wronged, rejected, angry, and afraid. There were no grief counselors or therapists in places like Moab in those days and life was hard. Little boys were taught that men never cry, no matter what.

But all of that pent-up emotion, frustration, and anger had to go somewhere. If he couldn’t cry, he had to strike out, somehow. Young Bill Tibbetts became the toughest, and maybe the meanest, kid in Moab.

Chapter 4

A Child of the Wilderness

Childhood didn’t last long on the Utah frontier. Kids as young as five and six had chores to do around the house and barn, and most began working in the fields before they were ten. Agriculture was a very labor-intensive occupation in the days of horse-drawn farm machinery and the whole family was involved in making a living.

While living with his grandparents on their farm in Moab, Bill learned all about hard work and responsibility at an early age. He milked the cows, cleaned the chicken coop, and chopped his share of the firewood. He learned the farming business by digging in the dirt, and his uncles taught him the skills of a cowboy. By his teenage years, he was an accomplished horseman who could throw a rope with the best of them.

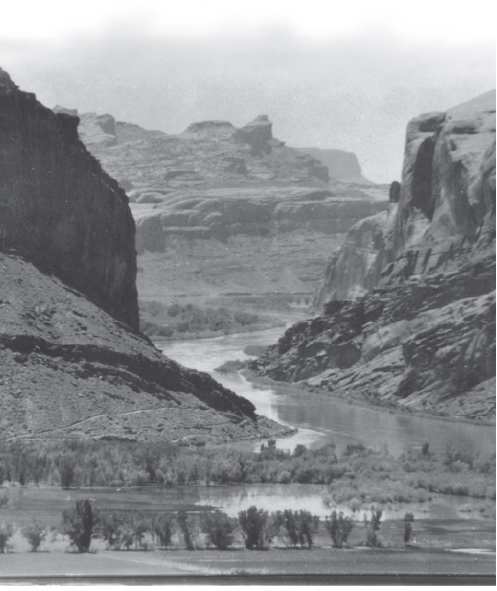

While still a boy of tender age, Bill began working for the Murphy Cattle Company, a large ranching enterprise headquartered in Moab. With the Murphy outfit he spent his summers in the land between the Green and Colorado rivers, the Big Flat, Upheaval Dome, and Island in the Sky country north and west of Moab. Part of that cattle range is now the northern end of Canyonlands National Park. The land was raw, wild, and undeveloped when Bill first saw it, and he fell in love with the place.

It was not unusual in those days for boys as young as ten or twelve to work for the big cow outfits. Boys that young might have been too small to rope steers and wrestle calves for the branding iron, but they could ride a horse and help move livestock to greener pastures. Kids also worked as camp tenders, gathering firewood, fetching water, wrangling horses, and helping the chuckwagon cook. They helped to set up and take down the camp, peel potatoes, wash dishes, harness the team, and tend a few doggie calves. Sometimes there was even a cow to milk.

Part of Bill’s job with the Murphy cattle outfit was digging out waterholes and making small earthen dams to catch runoff water for the cows. To do this, he ran a Fresno, a large, metal-bladed wooden scoop that was pulled behind a horse or a team of horses. Fresnos were the principal tools of road and railroad construction in those days. Operating one would have been a big job for a kid. The machine was called a Fresno because they were manufactured in Fresno, California, and the word “Fresno” was painted on the sideboards.

In the early 1900s, when Bill worked for the cattle company, much of the land in southeast Utah was still untamed, unnamed, unmapped, and unexplored. Even the old-timers often had no clue about what was at the head of the canyon or around the next bend of the river. To a bold and adventurous boy like Bill Tibbetts, the place was magic. Buffalo Bill and his Wild West Show offered nothing young Bill couldn’t find in his own backyard. In the canyons around Moab, real old-time cowboys still bucked-out wild horses and chased long-horned cattle with bullwhips and ropes. Renegade bands of non-reservation Utes and Paiutes still skulked in the mountain shadows, while up any side canyon might be a major cliff dwelling, a lost city of stone ten thousand years old.

Somewhere in the canyons there was sure to be a vein of pure silver or gold, eight or ten feet thick, or a lost Spanish mine, or Montezuma’s hidden treasure. There were caves to explore, ancient Indian picture writings to decipher, and deer and mountain sheep waiting to be hunted for camp meat. There were arrowheads scattered around the waterholes and colorful nodules of agate and quartzite littering the hillsides. Whole petrified trees were lying just as they fell when the Biblical flood of Noah knocked them to the ground. There were catfish in the river, herds of antelope on the grasslands, rattlesnakes in the rocks, and eagles nesting on the mesa tops. The world was new and the whole country waited impatiently to be explored.

Young Bill did his best to see it all. On horseback and on foot he traversed the canyons and the mesas, exploring ruins, climbing to the top of rocky overlooks, peeking into dark caves and fissures in the rocks, following watercourses and game trails over the canyon rims. He traveled the cowboy and outlaw trails, discovering where they began and where they ended. He learned to navigate the canyon country and keep track of where he was by keeping a bearing on the sun and prominent landmarks on the horizon. His guideposts were the snowy tips of the La Sal Mountains to the east, the Blue Mountains to the south, the hazy peaks of the Henry Mountains far to the southwest, and the long ridge of the Book Cliffs to the north. At night, while camping out for weeks on end, he memorized the night sky, watching the constellations circle the North Star as the moon pirouetted through her phases.

As a boy, Bill learned to survive in the desert. His uncles taught him to follow game trails to find hidden sources of water deep in the canyons, and he learned to dig in the damp sand against the ledges to tease a drink of water from a tiny seep of a spring. He learned which desert plants were edible and which ones would kill a horse. He learned to dig sego bulbs and Indian potatoes, how to gather pinyon nuts and eat a prickly pear cactus. He learned how to catch a rabbit by using a forked stick or a length of barbed wire to pull it from its den. He learned to trap, hunt, and prepare wild game for the cooking pot. He learned how to camp and sleep comfortably at night

without a bedroll or blankets. He discovered that he could go all day without a drink of water, and two or three days without food, if he had to. Growing up on the desert made him tough and self-reliant.

By his mid-teenage years, Bill was a survivalist. He could live on the desert like an ancient Paiute, relying solely on wit, instinct, and woodcraft. His survival skills and intimate knowledge of the canyon country would serve him well in the years to come.

Sometime in those early years, Bill discovered a hidden cave in an area known today as Arches National Park. He used a rope and an oiled-rag torch to explore the cave by himself, and he carved his name on an interior wall. In 1946, he took his sons there to show them his secret place. His youngest son, Ray, carved his name in the cave beneath his father’s 1917 inscription. The cave remained a Tibbetts family secret until it was found by hikers and reported to the park service in 1987, some seventy years after Bill had carved his name there.

NEXT TIME…Indian Wars, Horse Thieves, and Outlaws.

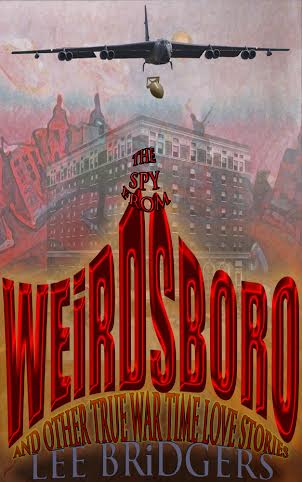

All images from the book ‘LAST OF THE ROBBERS ROOST OUTLAWS: Moab’s BILL TIBBETTS’ …By Tom McCourt. Buy the book here.

To read the PDF version of this article, click here and here.

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!

|

|