Introduction

On September 4, 2012, I submitted a comment to the Zephyr on Lloyd Pierson’s article on “Moab’s Concentration Camp,” published in the June/July 2012 issue of The Canyon Country Zephyr. In his article, Pierson discussed a facility at a former Civilian Conservations Corps camp near Dalton Wells, Utah, managed by the War Relocation Authority (WRA) during World War II. I mentioned that my father was imprisoned at another WRA facility located at nearby Topaz, one of ten larger camps hastily constructed to imprison Americans of Japanese ancestry following the commencement of hostilities between the United States and the Empire of Japan after its attack on Pearl Harbor. Recently, Tonya Stiles asked me to write a follow-up article, chronicling the lives of my parents and how camps like the ones located in Moab and Topaz, impacted their lives.

My recollection is similar to hundreds of other articles, essays, and remembrances written and published by families of formerly imprisoned Japanese-American men and women, now in their eighties, nineties, older, or deceased.

Topaz, Utah. A panorama view of the Central Utah Relocation Center, taken from the water tower. (Photo Credit-Wikipedia)

The hope is to record individual oral histories about their World War II experiences before…, well, before it becomes too late. Both my parents, John and Amy Mikuni, have passed away, Dad in 2003 and Mom in 2013, but fortunately, we did have a little time to discuss “camp”. I am discovering that I have more questions to ask Mom and Dad, and, now, it IS too late. The World War II concentration camp experience was painful for the Japanese-Americans who were forcibly removed from their homes and unlawfully incarcerated for nearly four years, and many remained silent about their experiences for the rest of their lives.

Families were forced to leave their homes, their possessions, and their traditional family lives and shipped to remote places for unknown reasons. To these Japanese-Americans, Japan was an enemy, much like Germany and Italy, the other members of The Axis with whom the United States was at war. To be associated in any way with this enemy of my country was shocking, unbelievable, and hurtful.

This was particularly true of my parents. I recall as a pre-teen attending family gatherings after “the War” and he3aring Mom, Dad, my “Ba-chan” (grandmother), my “Ji-chan” (grandfather), and my uncles and aunts refer to someone they knew from “camp.” I presumed everyone was talking about Boy Scout or Girl Scout camp, because I only knew about those types of camps from my school classmates. When I asked my parents about “camp”, there was silence or a “never mind,” so I concluded I was correct.

Specific words or phrases in the Japanese language describe how Japanese people deal with situations like they endured in World War II. The Japanese term, “shikataganai”, when translated means “it cannot be helped.” Another term, “gaman” is loosely translated as “enduring the unbearable with dignity and silence.”

I understand the dangers of broad, sweeping generalizations about any group of people, but these terms characterize very well the demeanor of many Japanese-Americans, especially my parents, and how they felt about and dealt with the events surrounding their incarceration. Then, they found themselves having to move on with their lives in the aftermath. After the war, at mealtimes and during other Mikuni family times with my brothers, the subject was simply not discussed. It wasn’t until I took an Asian studies course during my time at Fresno State (I was 22 at the time), did I really learn about “the Camps,” although in an academic environment.

At first, I was, interestingly, angry at my parents for withholding their personal stories about the camps. I came to understand that it was simply too painful for them to discuss. My Asian studies instructor and my classmates expected me, since I was a “Sansei” (third-generation Japanese-American), to provide personal insights, observations, and other contributions to the class discussion. I had none to offer because I was totally clueless about the topic. I did not personally experience the camps, since I was not born until after World War II ended and the camps had been closed. Thus began the long-delayed dialogue with my parents about their lives in “camp”. Incidentally, “shikataganai” and “gaman” were sprinkled throughout our conversations, and I even learned a little about the Japanese language. My parents chose not to teach my brothers and me the Japanese language out of a concern that being fluent in the language would subject Ron, Dennis, and me to a repeat of what happened in 1942. Being bi-lingual in what should have been my natural 2nd language would have been advantageous in today’s global economy, but, shikataganai.

The United States Government, both during and following World War II, used terminology as a means to moderate the public perception of the severity and extremes of its actions, now recognized as illegal. For instance, in many public official documents of the time, the term “non-aliens” is used to denote American CITIZENS of Japanese ancestry. This euphemistic tactic was intended to prevent the formulation of the logical question from the public, “why are American citizens being rounded-up and imprisoned”?

Even the Japanese-American community had for many years mistakenly and incorrectly continued to use the euphemistic wartime terms, perhaps as a means to minimize their own pain and embarrassment. As William Safire, noted author, stated: “To some degree, euphemism is a strategic misrepresentation.” In this article, I use the currently accepted terminology for the wartime situation with a reference to the euphemistic term, e.g., “citizen (PKA (Previously Known As) non-alien)”. It is interesting to note here that even the name of the Federal agency responsible for the forced removal and incarceration of Japanese-Americans, the War Relocation Authority, was a euphemism. Its proper name should have been “War Forced-Removal-and-

This article is my first formal effort to document my parents’ journeys leading to, their time during, and following, their World War II experience. My informal research began with those chats with Mom and Dad in 1969, and continuing as my brothers and I prepared for Mom and Dad’s 50th wedding anniversary in 1996. Thanks to Tonya’s request, I am now able to complete the work, and to share it with the Zephyr.

Mom – Amy Yemiko (Takeuchi) Mikuni

My mother, Amy, was a “Nisei”, or second-generation Japanese-American. She was born in 1922 in Del Rey, California, about 15 miles southeast of Fresno, in the Central Valley of California. Her father, Waichi Takeuchi, was born in Japan and immigrated to the United States in 1901. Her mother, Ayano Tomosuye, was born on the Big Island of Hawai’I, in what was then, Territory of Hawai’i. She left Hawai’I to travel to Japan for her schooling, and arrived in California in 1920.

I am presuming that my grandmother was a “picture bride”, since her wedding year and her arrival year were both 1920. My grand-parents were considered “Issei”, or first-generation Japanese Americans, who, because of alien exclusion laws in place at the time, were prohibited from becoming naturalized citizens. “Issei” is generally accepted as the term for the first generation of immigrants from Japan, but my grandmother was actually, technically, born on American soil, and became naturalized. Mom and her family (Waichi and Ayano, sisters Mats and Erma, and brothers Harry, Ken, Dan, Floyd, Leo, and Victor), operated a farm west of Fresno.

Due to the California Alien Land Laws in existence at the time, my grandparents were prohibited from owning property. However, the land upon which the Takeuchi family lived and raised strawberries, grapes, and peaches, was purchased in the name of my Uncle Harry, the eldest of the Takeuchi sons. Mom helped with caring for her younger sister and brothers, worked on the family farm, and continued her schooling in local schools until her 1939 graduation from Central High School in Fresno.

Dad- John Shigeo Mikuni

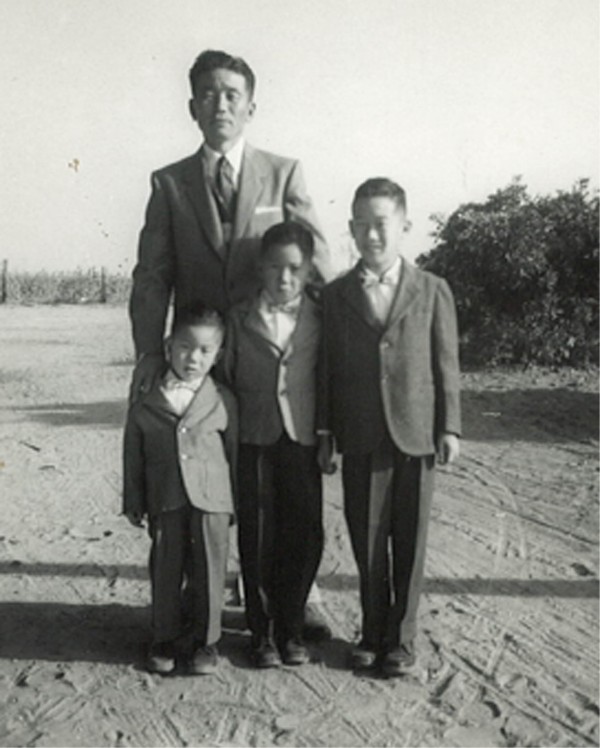

My Dad, John Mikuni, and brothers (L-to-R) Dennis (age 3), Ron (age 7), and me (age 9) at our Fresno farm.

My father, John, was born in 1920 in Walnut Grove, California, about 30 miles south of Sacramento. My father’s parents, Daikichi and Matsu Mikuni, immigrated to the United States in 1916, and settled in the Sacramento Valley in California to work in agriculture. Although technically a “Nisei” because he was born in the United States to “Issei” parents, Dad was considered a “Kibei”( like Harry Ueno in Lloyd Pierson’s Zephyr article). Dad traveled to Japan with his parents as an infant, and attended elementary school and high school in the city of Iwakuni . He then returned to the US and California in 1937 to join his older sister in Oakland. His other older sister arrived from Japan in San Francisco about 2 months later. Dad‘s parents, Daikichi and Matsu, remained in Japan. Dad lived with his sister Yuriko, her husband, and 2 nephews and niece in Oakland where he helped with the family gardening business. His other sister, Fumiko, later moved to Los Angeles.

December 1941 to May 1942

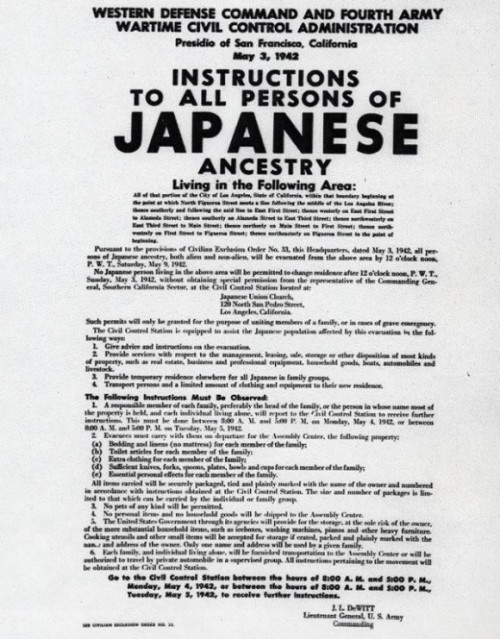

After the United States declared war on the Empire of Japan after its December 7, 1941 surprise attack on Pearl Harbor, American citizens and legal residents of Japanese ancestry immediately came under intense scrutiny and suspicion. ALL Japanese, regardless of citizenship or resident status, were immediately assigned blame for, or associated with, the sneak attack on Pearl Harbor, and the scope of the suspicion soon expanded to potential espionage, sabotage, and subversion. Thus, on February 19, 1942, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066, which provided for the protection of national security assets in military zones, such as the Pacific Coast. Citizens and resident aliens of Japanese ancestry residing in these designated military zones were considered threats to the national security, and were directed to be forcibly removed (PKA evacuated) from those military zones. Beginning in May of 1942, notifications, such as the one posted in the Los Angeles area [pictured], appeared in major population centers on the Pacific Coast, such as Oakland and Fresno in California.

Japanese-Americans and resident-aliens throughout the military security zones were directed to report to Wartime Civil Control Administration (WCCA) temporary detention centers (PKA Assembly Centers) designated for residents of those localities. In Fresno, the temporary detention center was located at the Fresno Fairgrounds. In preparation to vacate their farm, Mom’s family gathered whatever personal items they were allowed to take with them, and prepared to leave their family home. A family friend from nearby Reedley, Mr. Herman Neufeld, purchased the 40-acre Takeuchi ranch, and graciously promised to help the family after the conclusion of the war, whenever that might be. Mom’s family (WRA family #12483) then reported to the unknowns of the Fresno Fairgrounds and the future.The Fresno detainees remained in the fairground horse stables from May through October 20, 1942, when their train travels began to the War Relocation Center in Jerome Arkansas.

For residents of the Oakland, Berkeley, and Alameda area, the WCCA temporary detention center was located at the Tanforan Race Track in San Bruno. Dad, his sister, brother-in-law had to sell or store their personal property, gather up whatever they could carry with them, and travel across the San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge to San Bruno and the Tanforan Racetrack. The housing and related facilities for the Japanese-American detainees in both Fresno and Tanforan, as well as most other WCCA centers, consisted of horse stables, complete with hay and manure, and hastily erected tents and barracks constructed in the infield areas of the race tracks. Dad and his sister’s family (WRA family #20680), along with other San Francisco Bay Area detainees remained at the Tanforan horse stables from May through September 15, 1942, before being transported by train to the War Relocation Center in Topaz Utah.

Topaz Utah

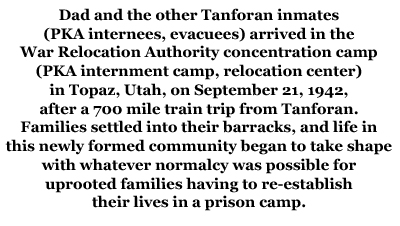

Dad and the other Tanforan inmates (PKA internees, evacuees) arrived in the War Relocation Authority concentration camp (PKA internment camp, relocation center) in Topaz, Utah, on September 21, 1942, after a 700 mile train trip from Tanforan. Families settled into their barracks, and life in this newly formed community began to take shape with whatever normalcy was possible for uprooted families having to re-establish their lives in a prison camp.

During the time Topaz was in operation, 11,212 people spent time at the camp, with a peak of 8,130 in 1943. Like any community, the entire spectrum of jobs that must be done in order for the community to function properly had to be identified and put into operation. The WRA, the agency charged with operating the camps, provided an important supply and oversight role, in addition to armed guards and patrols, but the residents provided the necessary skills and labor to accomplish the day-to-day operations.

Dad was 22 when he arrived at Topaz, and was able to contribute his energy and skills to helping the community function. He participated as he could as a worker, spending time with construction, maintenance, and cooking in the mess hall. Inmates were paid roughly $12 to $19 per month for the various jobs they carried out for the camp community. In addition to work, there was leisure time… a lot of leisure time. Like most young American men, Dad loved baseball, and played on the Topaz team. Dad was a catcher, and a foul-tip broke the pinkie finger of his right hand, which he never had treated or reset. He loved to show off his crooked pinkie finger to my brothers, me, and anyone else who asked about it, and to talk about playing baseball in camp, one of the few things about camp he did discuss freely. A 2007 movie, American Pastime, provides a dramatized, fact-based, look at baseball in a WRA concentration camp. Amateur movie footage, taken by a camp resident using a movie camera smuggled into Topaz, is included in American Pastime. There was a very brief segment of film taken at a Topaz baseball game, showing a catcher, but I cannot tell if, by chance, it was my Dad.

Dad was 22 when he arrived at Topaz, and was able to contribute his energy and skills to helping the community function. He participated as he could as a worker, spending time with construction, maintenance, and cooking in the mess hall. Inmates were paid roughly $12 to $19 per month for the various jobs they carried out for the camp community. In addition to work, there was leisure time… a lot of leisure time. Like most young American men, Dad loved baseball, and played on the Topaz team. Dad was a catcher, and a foul-tip broke the pinkie finger of his right hand, which he never had treated or reset. He loved to show off his crooked pinkie finger to my brothers, me, and anyone else who asked about it, and to talk about playing baseball in camp, one of the few things about camp he did discuss freely. A 2007 movie, American Pastime, provides a dramatized, fact-based, look at baseball in a WRA concentration camp. Amateur movie footage, taken by a camp resident using a movie camera smuggled into Topaz, is included in American Pastime. There was a very brief segment of film taken at a Topaz baseball game, showing a catcher, but I cannot tell if, by chance, it was my Dad.

Soon after accomplishing the forced removal and incarceration orders stipulated by Executive Order 9066, the US Government realized that follow-up actions were needed to determine if there were, indeed, disloyal individuals among those incarcerated (PKA interned). It was also recognized that the “camps” could be a source of draftees and volunteer military personnel for service in the US Army’s all-Japanese-American 442nd Regimental Combat Team, the 100th Battalion, or the Military Intelligence Service.

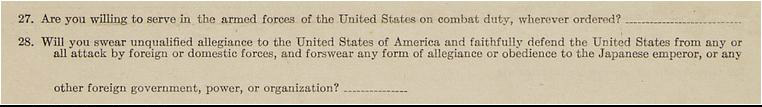

Late in 1942, in an attempt to segregate “loyal” inmates, that is, those suitable for military service from the “disloyal,” WRA camp inmates over the age of seventeen were forced to complete Selective Service Form 304a – “Statement of United States Citizen of Japanese Ancestry”, colloquially known as the “Loyalty Questionnaire”. Most questionnaire items dealt with the usual general information topics, such as, family members, residences, organizations, education, etc., but responses to two specific questions, numbers 27 and 28, were of particular interest to War Department.

Question 27 asked if the individual would be willing to fight for the US, and Question 28 inquired if the individual would disavow allegiance to the Emperor of Japan. After many years of post-war analysis, both questions were determined to be flawed in their presentation, but 1942 and 1943 respondents had to answer them regardless of how confusing or inflammatory they may have been at the time.

For instance, Question 27 asked individuals if they would fight for the United States, the same United States that stripped them of their rights as citizens, and imprisoned them as criminals without due process. Question 28 asked individuals if they could declare that they no longer held allegiance to the Emperor of Japan. This was a difficult concept because 1) many individuals never held allegiance to the Emperor in the first place; and, 2) because of alien exclusion laws, many Japan-born resident aliens could not become naturalized citizens, so their ONLY allegiance was to the Emperor. Disavowing allegiance to their ONLY Nation would have rendered these inmates as “stateless” individuals.

Dad, again being the young man he was, had a rebellious streak. He didn’t appreciate the fact that as an American citizen, he had been imprisoned unjustly, simply because he resembled an enemy of the United States. He answered both questions “no.”

Reactions at Topaz and the other WRA camps to Questions 27 and 28 were likely rooted in protest and resentment, rather than in disloyalty and allegiance to Japan, but the results remained. Like Dad, approximately 12,000 of the 78,000 who responded to the questionnaire answered “No” to both Questions 27 and 28. Individuals in this group, known as the “No-No Boys,” were identified and scheduled for segregation to separate them from the general camp populations. A “Citizen Isolation Center” facility was established in Moab Utah for the No-No Boys and other recalcitrant camp inmates, but the group became too large for Moab. As was described in Lloyd Pierson’s article, Moab was used on a limited basis for a select group of detainees.

Reactions at Topaz and the other WRA camps to Questions 27 and 28 were likely rooted in protest and resentment, rather than in disloyalty and allegiance to Japan, but the results remained. Like Dad, approximately 12,000 of the 78,000 who responded to the questionnaire answered “No” to both Questions 27 and 28. Individuals in this group, known as the “No-No Boys,” were identified and scheduled for segregation to separate them from the general camp populations. A “Citizen Isolation Center” facility was established in Moab Utah for the No-No Boys and other recalcitrant camp inmates, but the group became too large for Moab. As was described in Lloyd Pierson’s article, Moab was used on a limited basis for a select group of detainees.

Incidentally, of the 11,212 Topaz detainees, 451 joined the US Army, 80 as volunteers and 371 as draftees, to serve with distinction in the 442nd Regimental Combat Team and the 100th Battalion. Fifteen of those Topaz servicemen were killed-in-action. Dad and a select group of other Topaz inmates began their 800 mile, 5-day train trip to the newly designated WRA “Segregation Center” in Tule Lake California on September 15, 1943, to join Tule Lake camp residents and the No-No Boys from the other eight WRA Centers.

Coming next time:A wedding at Tule Lake, and Life after the Camps…

Alan Mikuni lives in Fremont, CA.

To read the PDF version of this article, click here and here.

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!

There is an excellent book about the Japanese American detainees who would not cooperate with the draft program: “Free to Die for Their Country: The Story of the Japanese American Draft Resisters in World War II,” by Eric Muller, University of Chicago Press, 2001.

A book about the shameful and incompetent federal decisions regarding the Japanese internment is “By Order of the President: FDR and the Internment of Japanese Americans,” by Greg Robinson, Harvard University Press, 2001.

A third book is “City in the Sun, the Japanese Concentration Camp at Poston, Arizona, by

Paul Bailey, Western Lore Press, 1971. Paul Bailey also wrote some books about Mormon History and Native American and Mormon Biographies.

Herman Neufeld was my great Uncle. I knew him as a very small child and only remember him through the eyes of a child. It is gratifying to see him mentioned in this article, as I was actually just doing some research to write my mother’s obituary (she passed recently) and Herman was her favorite Uncle. I came across this article post on a google search for his name. Thanks for the great summarization of this terrible time in our history. I live in Visalia (down the road from Reedley) and can tell you most people under the age of 20 in this area have no idea.

Dear Alan, Thank you for your research and beautiful rendition of a time most of my friends’ parents and my mother and grandfather have never talked about nor forgotten. My Japanese mother experienced a similar but completely different story having grown up on Hawaii during the war and later in Reedley after the war. Please give my fondest greetings to your brother, Ron who I haven’t seen since FSC days in chemistry classes. I would love to hear from him! We have shared many hard times trying to pass chem exams together. Thank you again.

Wayne