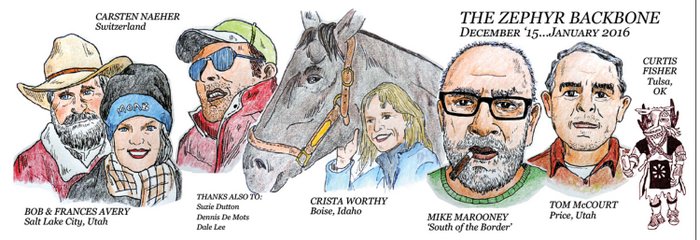

THANKS to Tom McCourt & the Tibbetts Family.

For years, I have been watching Moab move farther and farther away from its roots, to the point where it seems few people even know the history of the place anymore. Some of them don’t know OR care, but I think there are still many who have a respect for the past (I hope so, at least).

Last winter I read Tom McCourt’s book on Bill Tibbetts and think it’s his finest work. I knew a bit about Bill,

but the story was told so beautifully and I felt it was a very moving tribute, not just to Bill, but to those far off times.

I see Moab as some alien world now, and I feel the most significant contribution I can make with the Zephyr these days, is to try and preserve the past in some fashion, or at least make it available for those readers who are interested. With Tom’s permission, the Canyonlands Natural History Association who published it, and with the good wishes and approval of Bill Tibbetts’ son Ray and the Tibbetts Family, we are pleased and honored to offer, over the next few months, excerpts from Tom’s excellent portrayal of ‘the Last Robbers Roost Outlaw.” JS

Chapter 5

INDIAN WARS, HORSE THIEVES, AND OUTLAWS

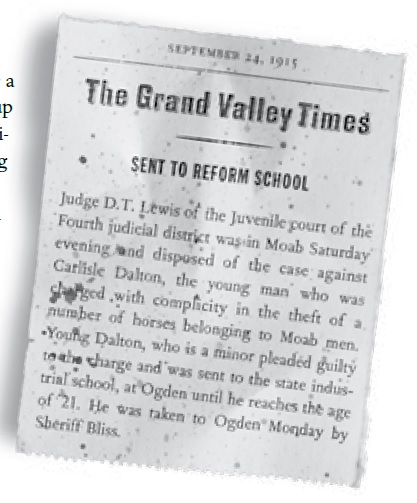

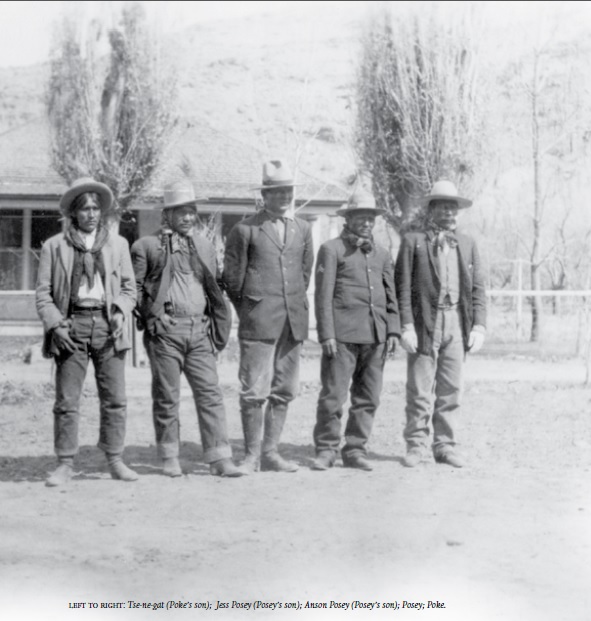

left to right: Tse-ne-gat (Poke’s son); Jess Posey (Posey’s son); Anson Posey (Posey’s son); Posey; Poke

In the spring of 1915, Bill Tibbetts turned seventeen. His school days were behind him and he was almost a man. He was growing up and growing restless in the small town of Moab and yearning to seek his fortune in the wide world of high adventure. Like most teenage boys in the first blush of young adulthood, he was feeling cocky, rebellious, and bulletproof. His troubled mood fit the troubled times.

Around the world, 1915 was a year of war and trouble. In Europe, the First World War was in its second year. Millions of men from many nations were fighting and dying in the muddy trenches of France and Belgium. American newspapers were full of shrill alarms and biased yellow journalism. Headlines spotlighted the evils of Kaiser Wilhelm and his spike-helmeted German troops. Editors and army generals were rattling sabers, but the country wouldn’t enter the war for another two years. South of the border, Mexico was deep in revolution. Pancho Villa

and his men were seizing control of the country. Closer to Moab, there was an Indian uprising in progress.

The Indian “war” of 1915 began when a San Juan County Ute, named Tse-ne-gat (meaning Crybaby, or One Who Cries a Lot), was charged with the murder of a Mexican sheepherder in Colorado. When Tse-ne-gat refused to voluntarily surrender to authorities in Utah, a rowdy and allegedly drunken civilian posse was sent to track him down. The posse was assembled in Colorado under the command of a U.S. Marshal.

The Colorado posse surrounded an Indian camp near the town of Bluff, Utah, in the early morning hours of February 20, 1915, and quickly got into a shootout with Tse-ne-gat and some of his Ute and Paiute relatives. A posse member was killed and two others wounded. One of the Indians was armed with a very modern 30-06 rifle and it took a while for the white guys to learn to fully appreciate the range and capabilities of the weapon. But the posse did a little better against the non-combatants in the Indian camp. According to newspapers, “a squaw and two

papooses” were killed in the ambush and two “old warriors” were captured. Tse-ne-gat and asmall group of armed and dangerous Indians escaped to the south toward Navajo Mountain. The Indian camp was burned.

Another group of five Indian men from a nearby “peaceful” Indian camp voluntarily surrendered to avoid the conflict, but one of them was shot and killed by a civilian guard while “trying to escape.” At the time, people in the town of Bluff called it a cold-blooded murder. The murdered Indian, a Ute named Havane, was well known and well respected in the little community. The trigger-happy guard was never charged with the murder. In fact, no one could explain why the “peaceful” Indians were being held under armed guard without being charged with a crime.

Shooting Indians was exciting stuff. There hadn’t been a good Indian war in southeast Utah since the 1880s and the whites were due to win one. They had lost the last two: the “Pinhook Massacre” of 1881, and the Fight at Soldier Crossing in 1884. Newspaper reporters caught the spirit of the thing, and, from the headlines of the day, the whole country was made to believe that San Juan County was in a full-fledged Indian war. The towns of Blanding and Bluff were said to be under siege, and dozens, maybe hundreds, of “hostile redskins” were lurking on the edge of town, lusting for white scalps. The whole country was up in arms and newspapers everywhere were screaming for federal troops.

In response to the threat, The War Department sent an army general to quell the Indian uprising. To everyone’s surprise, the wise and experienced old soldier came without cannons or soldiers. In just a matter of days, General Hugh L. Scott, through the aid of native interpreters, was able to sweet-talk old Tse-ne-gat and his father, Old Poke, along with another Paiute chieftain, Old Posey, into surrendering.

Tse-ne-gat agreed to be sent to Colorado to face the murder charges. But before he was sent to Denver for trial, Tse-ne-gat and the other “renegades” were compelled to meet with the governor of Utah and his entourage in the town of Bluff for a big “Pow-wow” and photo opportunity. Someone had to take credit for winning the “Indian war.”

Tse-ne-gat faced an all-white jury in the federal court in Denver. The evidence was weak and he was quickly acquitted. He returned home a free man. But while he was still being held in federal custody, Tse-ne-gat and three other “Indian troublemakers” were taken to Salt Lake City on a train to be paraded as trophies of the white man’s victory. The natives were given a grand tour of the city with newsmen, politicians, and photographers following them everywhere. Then, after

promising the governor that they would be good Indians from then on, the “defeated red men” were taken back to southern Utah and released into the wild.

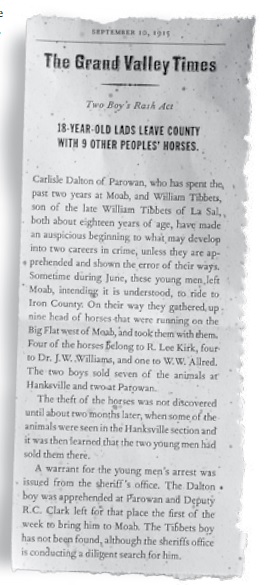

That’s how things were in the spring of 1915. There was lots of talk about war, murder, rampaging Indians, hate and revenge. It was an exciting time for a couple of teenaged boys to be camping out on the cattle ranges, all alone and far from the nearest settlement. In their youthful imaginations, there might be a “war-painted savage” behind any rock or bush. Young Bill Tibbetts and his friend

Carlisle Dalton kept a sharp eye out.

The young cowboys had been in the Big Flat country, near Island in the Sky, for three or four weeks. It was calving time and they were working for the Murphy Cattle Company. The boys were about the same age and they had become good friends over the past several months. They were sitting around an evening campfire when Bill spoke.

“What ya gonna do on payday, Carlisle? We’ve each got about twenty dollars comin’.”

Carlisle Dalton thought about it for a moment, poking at the campfire with a stick. Dancing flames cast moving shadows over his suntanned young face and his mood was quiet and somber. “I’ve been thinkin’ about goin’ home,” he said. “I haven’t seen my family in Parowan for a long time. I think I’d like to go home.”

“I’ve never been to Parowan,” Bill mused. “I haven’t been hardly anywhere except to La Sal and Monticello. Of course, I did see Green River when we took steers up there to put on the train. Those big ol’ steam engines are somethin’, I’m tellin’ you.”

“Well, Parowan is a lot different than Moab,” Carlisle said as he tossed another stick on the fire. “Parowan is in a big old valley with lots of grass and none of these darn bottomless canyons to cross. They ain’t got all this sand to wade in, either. And I don’t remember the gnats being as fierce and starved as these critters. They got civilized bugs over in Parowan. Yes sir, and that’s a fact.”

“I’ve never seen any civilized bugs,” Bill smiled. “And they’ve got some real purdy girls over in Parowan, too,” Carlisle said with an impish grin, “Real healthy girls.” “Holsteins,” he said, holding his cupped hands in front of his chest. “Not like those skinny things around Moab. I ought to take you over there and introduce you to some of my cousins. You’d throw rocks at Sally Tucker if I introduced you to my cousin Elsie.”

“Oh, knock it off,” Bill growled, trying hard not to smile. “I only danced with her twice before her momma took her home bawlin’ like a lost calf.”

“Yea, she’s sweet on you, all right. Too bad she’s only thirteen. I think if you ever ask her to dance again, her momma is gonna run over you like a wild-eyed old range cow, all stompin’ and blowin’ snot. You better be careful around that Tucker girl, my friend.”

“Aw, what can I say?” Bill grinned. “I’m such a handsome buck. The women just can’t resist me. It runs in the family, you know. My momma says my old man was about the handsomest bull calf this side of the Paradox Valley, and I got his steely gray eyes. The girls just can’t leave me alone.”

“Ain’t you somethin’,” Carlisle spat as he scooped up a handful of sand and threw it across the fire at Tibbetts. “Go get some firewood, you handsome bastard. I’ll stay here by the fire and try to keep the girls out of camp.”

Bill ducked and laughed out loud. “Maybe you better introduce me to your cousin Elsie,” he teased. “If I married her, we’d be in-laws as well as outlaws and you could invite us over for supper every Sunday afternoon. I’ll go all the way to Parowan with you if you’ll show me cousin Elsie and those civilized bugs you’ve been braggin’ about.”

“You got a deal,” Carlisle said. “After we settle up with old man Murphy, we’re on the road to Parowan. I just hope cousin Elsie doesn’t see you comin’ and go stampedin’ off down the valley. A homely feller like you might have to sneak up on a purdy girl like Elsie. Elsie is a perfect model of high-class culture and refinement and those snoopy gray eyes of yours will get your face slapped in a hurry, you mark my word. And her momma is a real wildcat compared to that lame and tame old momma cow who claims Sally Tucker. You try to kiss cousin Elsie and her momma will nut you with a dull deer horn, and that’s a fact.”

Hoots of laughter echoed out over the sand flats in the darkness. The hobbled horses raised their heads and looked back toward the firelight and the source of the happy sounds. Far off in the bottom of the canyon a coyote yipped and then howled mournfully. The innocent and carefree days of youth were almost at an end for the two young cowboys. Tomorrow would be a new day and the beginning of sorrows.

A few days later, the boys left Moab early in the morning. It was dark and the streets were empty. They had ropes and canvas slickers tied to their saddles and Bill had appropriated an extra horse from his stepfather’s corral to carry a light camp outfit. He didn’t ask permission to take the animal.

Winny Allred would surely be annoyed by his stepson’s insolence, but the teenager had done such things before, knowing that his stepfather would do nothing about it. Allred thought more of keeping the peace with his strong-willed wife than bickering with her smart-alecky oldest son. Bill took full advantage of the situation and thoroughly enjoyed tormenting his stepfather.

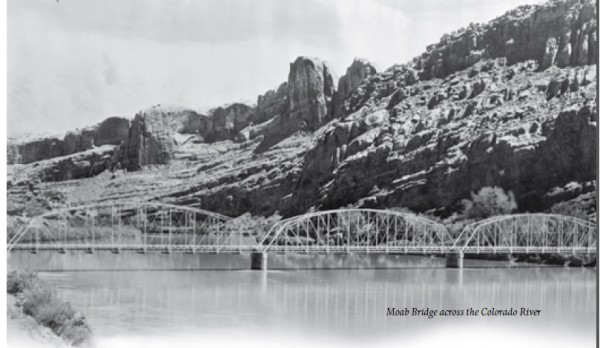

The young men crossed the river on the new iron bridge without meeting any other travelers. A dog barked from near a squatter’s shack as they crossed Courthouse Wash and followed the road along the river. The sun finally spilled over the mountains and splashed down on them as they turned the horses up Moab Canyon, headed north.

“How much money you got, Bill?” Carlisle asked

.

“Little over seven dollars.”

“That ain’t much to be showin’ off for cousin Elsie with,” Carlisle teased.

“I had to finish payin’ off this saddle,” Bill replied. “And I had to buy me a new shirt. Gotta look good fer cousin Elsie, you know. I gave my grandma a couple a bucks to help with the groceries, too. She’s been real good to me. She didn’t want me to go on this trip with you, either,” Bill said with a big grin. “She said I’d just be getting into trouble goin’ all the way to Parowan with an outlaw like you.”

Carlisle smiled but didn’t say anything.

“I think we ought to take a shortcut,” Bill said as they neared the top of Moab Canyon. “Uncle Will says it’s a long ways to Parowan if we follow the road through Green River, Price, and Salina. I think we ought to follow the old Horsethief Trail down to the Green River at the mouth of Mineral Canyon. We can cross the river there, and Hanksville is just across the Robbers Roost, somewhere over near Factory Butte. I ain’t ever been there before, but Uncle Eph pointed out the landmarks last year when we took some of his steers to Green River to sell. I’m sure I can find the place. From Hanksville, they say there’s a good road that goes west along the Fremont River toward the settlements in Iron County. I think it might be shorter to go that way and we can go swimmin’ in the river, too.”

“I’ve never been down the Horsethief Trail or through the Robbers Roost,” Carlisle confessed. “But if you say it’s the best way, then I’m all for it. By the way, why do they call it the Horsethief Trial?”

“Uncle Ephraim says the trail was used by a bunch of horse thieves back in the early days,” Bill explained. “The outlaws were usin’ the trail to steal horses from the ranchers near Moab. The bad guys would sneak up on the mesa, steal the horses, and then go back down the trail to hide out in the Robbers Roost.”

“Are those outlaws still out there on the Roost somewhere?” Carlisle asked.

“No,” Bill said. “Eph claims the ranchers caught some of them and hanged them in the cottonwoods down along the river near Tidwell Bottom. They never contacted the sheriff or anything; just hanged the outlaws and buried them in the sand along the river. Most people never knew anything about it. Eph said it was easier that way. The ranchers didn’t have to go to a lot of bother with a trial and all. After that, the outlaws went someplace else to steal horses.”

At the top of Moab Canyon, not far from a stagecoach stop called Courthouse Station, the boys left the well-traveled road and turned west up Seven Mile Canyon. They were going to the high mesa country where they’d been tending cows just a few days before. They camped that afternoon near a water hole in the Big Flat country on top of the mesa.

Early the next morning, the eastern sky was awash in brilliant orange when a band of horses came to the stock pond for a cold drink of water. The boys were squatting around a smoky campfire, frying bacon and dough-gob biscuits in a small iron skillet and trying to get warm. They recognized the horses. They had seen them many times before. The animals ran free in the high mesa country even though they were domestic stock and not wild mustangs. Ranchers often

turned “extra” horses loose to forage for themselves. Running free on the range for a year or two was a great way to teach a colt to be sure-footed in the rough country.

“Those are sure some pretty horses, ain’t they, Carlisle?”

“Yeah,” the Dalton boy agreed. “I think that big sorrel is one of old Doc William’s horses. He had him in town for a while, if that’s the same horse, and I think it is.”

“Wouldn’t it be somethin’ to have so many horses you could just turn half-a-dozen of ‘em loose to run with the cows out here?” Bill sighed. “It sure doesn’t seem fair. I had to work almost two years to buy this one little mare of mine, her and the saddle, of course.”

“I wonder how many of those range horses those rich guys lose to lions and wolves and such,” Carlisle questioned.

“And outlaws,” Bill reminded him. “There’s been many a good horse stolen out here on the open range.”

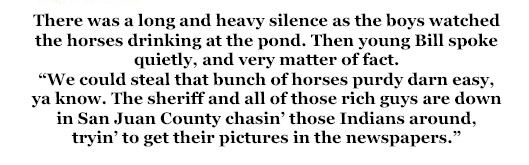

There was a long and heavy silence as the boys watched the horses drinking at the pond. Then young Bill spoke quietly, and very matter of fact. “We could steal that bunch of horses purdy darn easy, ya know. The sheriff and all of those rich guys are down in San Juan County chasin’ those Indians around, tryin’ to get their pictures in the newspapers.”

There was a long and heavy silence as the boys watched the horses drinking at the pond. Then young Bill spoke quietly, and very matter of fact. “We could steal that bunch of horses purdy darn easy, ya know. The sheriff and all of those rich guys are down in San Juan County chasin’ those Indians around, tryin’ to get their pictures in the newspapers.”

“That’s a fact,” Carlisle agreed. “And with all of the Indian troubles in the district this spring, I’m sure that old Posey, or that other buck, old Senna-guts, or whatever his name is, would be happy to take the blame. Them Injuns is horse stealin’ fools.”

“By darn, we could do it, couldn’t we?” Bill said quietly, thinking it over.

“I’ll bet they’re worth four hundred dollars,” Carlisle said, beginning to sound excited. “Even that colt would bring a good price. You could sure show cousin Elsie a good time with that much money, and that’s a fact.”

“What would we do with ‘em?”

“We could sell them in the settlements over in Iron County,” Carlisle said eagerly. “Nobody from Moab ever goes over there. Besides, it might take old Doc Williams and those other rich guys months to miss those range horses. And when they do, they’ll just figure the Indians got ‘em or the wolves ate ‘em up and scattered the bones.”

“I wonder where old man Murphy’s cowboys are workin’ this week,” Bill said in a sneaky tone of voice. “Let’s ride to the top of the ridge and see if there’s anybody around.”

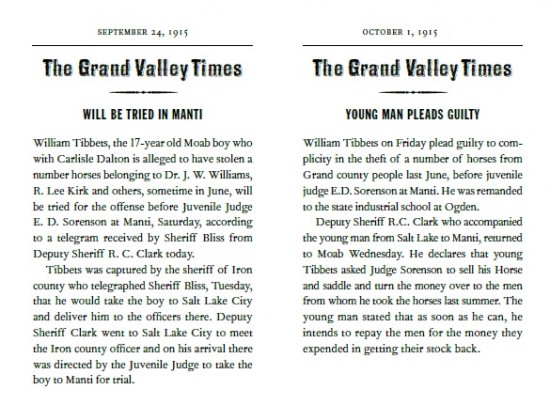

The sun hadn’t peaked in the noonday sky before the boys dropped off the steep rim of the canyon, headed down the Horsethief Trail. Before them they drove eight fine-looking horses, all sweaty and covered with foam. Bill was still leading the packhorse he had commandeered from his stepfather. In the eyes of the law, that made nine.

From a high rim above the river, the boys paused to look down on that wide expanse of desert and canyons known as the Robbers Roost. It was the last wild remnant of the Old West, the former hideout and wilderness sanctuary of such notables as Butch Cassidy, Harry Longabaugh, Tom Dilly, and Matt Warner. By late afternoon, the young horse thieves had crossed the river, headed west. Later that night their campfire was the only light to be seen anywhere in the six hundred square miles of the Robbers Roost.

Early the next morning, the boys started west to find the Hanksville road. Not knowing the country, they followed a trail Bill was familiar with, the cow trail that took Ephraim’s cows to market in the town of Green River. Bill had been over the route the previous fall and he remembered the landmarks. The cow trail took

them farther north than they wanted to be, but it would put them on the Hanksville road near the San Rafael River.

Late that afternoon, as they approached the San Rafael, they heard shooting coming from the direction of  the river. The boys rode to the top of a ridge to check it out. Below them they saw an old man running across a plowed field while two men with rifles were shooting at him from the edge of the field. As they watched, the old man staggered, stumbled, and went down. To the young cowboys, it looked like a cold-blooded murder.

the river. The boys rode to the top of a ridge to check it out. Below them they saw an old man running across a plowed field while two men with rifles were shooting at him from the edge of the field. As they watched, the old man staggered, stumbled, and went down. To the young cowboys, it looked like a cold-blooded murder.

Not wanting to get mixed up in a murder, the boys went back to their stolen horses and very quickly got the hell out of there. They cut the Hanksville road in short order and went south as fast as they could travel.

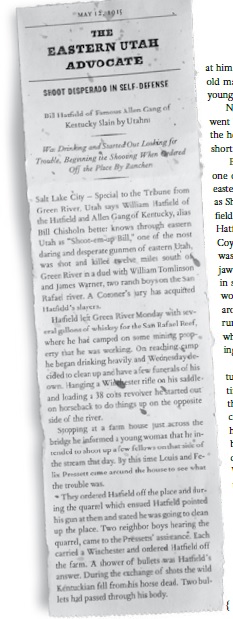

Bill and Carlisle found out later they had witnessed one of the most famous shootings ever to happen in eastern Utah. The victim was a bad man known locally as Shoot-em-up Bill. His real name was William Hatfield, and he was said to be a member of the famous Hatfield clan from Kentucky who feuded with the Mc-Coys. The story might have been true because the man was no stranger to gunplay. His bad hip and crooked jaw were reminders of old gunfights when he finished in second place. People said ol’ Shoot-em-up always wore his six-guns, and he was always waving them around and threatening to kill people. There were rumors of a warrant for his arrest over in Colorado where he had killed a woman by mistake while fighting with her husband or boyfriend.

Shoot-em-up had come to Utah to seek his fortune prospecting in the Henry Mountains, but at the time of his death he was living in a dugout across the San Rafael River from the Tomlinson Ranch. It came out in a coroner’s inquest that Shoot-em-up had gotten drunk that day and had gone to a neighboring farm where he was terrorizing an older couple with his guns, threats, and vile language. When another neighbor intervened, ol’ Shoot-em-up took a shot at him, and missed.

It wasn’t the first time farmers along the river had been tormented and bullied by the pistol packin’ old scoundrel and they were tired of it. A couple of young men loaded their rifles, ran old Shoot-em-up down, and put him out of his misery.

An inquest was held in the town of Green River a few days later. A coroner’s jury ruled that Shoot-em-up had met his death as the result of a justifiable homicide.

The men who did the shooting were defending their homes and families and no charges were filed.

Ephraim Moore attended the inquest in Green River and heard the testimony of the shooting firsthand. But by the time the inquest was held, two unknown eyewitnesses, Bill Tibbetts and Carlisle Dalton, had passed through Hanksville and were basking in the promised land of Parowan with their pockets full of silver dollars.

All images from the book ‘LAST OF THE ROBBERS ROOST OUTLAWS: Moab’s BILL TIBBETTS’ …By Tom McCourt. Buy the book here.

Click Here to Read the Previous Installments…

To read the PDF version of this article, click here and here.

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!