“….there have been some, even in the Park Service, who advocate spraying Delicate Arch with a fixative of some sort — Elmer’s Glue perhaps or Lady Clairol Spray-Net.”

-E. Abbey

Desert Solitaire

When I first read that passage by Abbey, I thought he was kidding; I learned, over the years, to take some of Cactus Ed’s “facts” with a grain of salt. The idea of spraying Delicate Arch with a fixative was too ridiculous to be taken seriously. This, of course, was before my decade of employment with the federal government.

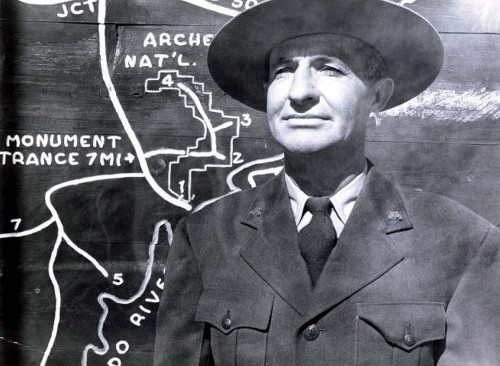

During my first winter at Arches, when the tourists were few and far between, I spent much of my day rummaging through file cabinets reading old monthly reports and looking at the black & white photo collection. One day, a labeled folder caught my eye. It read: Delicate Arch Stabilization Project. I remembered the remark in Desert Solitaire but still couldn’t quite believe my eyes.

What I found inside was a decade’s worth of memorandums, letters, and reports, all dedicated to the question – should the Park Service save Delicate Arch from imminent collapse?

The issue was first raised by Arches Custodian Russ Mahan on August 28, 1947 in a memo to the Regional Director. On a recent hike, Russ had observed “the eroded condition of the east leg of Delicate Arch … It is my opinion that some measures should be taken to prevent further erosion and to stabilize this particular point. If we lost this arch we would be losing one of the most important features of Arches National Monument.”

Mahan was convinced apparently that the collapse of Delicate Arch might very well take away any incentive to visit the park at all. If that were true, I’d go out there with a load of dynamite tomorrow.

In any case, the letter got the ball rolling, but just barely. The acting Regional director sent Mahan’s concerns to the Director in Washington. “There was,” he added, “the possibility that (the) condition of the formation may endanger visitors there.” But the threat of an arch squashing innocent tourists was not enough to elicit much interest. The next memorandum, dated September 13, 1951 said only that, “with specific data, previously lacking, the matter can be discussed again to determine what action, if any, this office is willing to recommend.”

Obviously, there was not a great deal of enthusiasm for this project. But 18 months later, interest was re-kindled when Southwest Regional Assistant Director Hugh Miller visited the arch and threw his support behind the plan:

“I have decided to join, as a result of this trip, those who believe that stabilization of Delicate Arch is warranted. I would favor the proposal only with the understanding that a very simple plaster jacket could be placed over the weak point in the arch at which erosion threatens to topple it, sufficient only to arrest further erosion at that point. Careful staining would suffice to make such minor support unobjectionable in appearance and it seems to me that it might reasonably be effective. From my own point of view, the Delicate Arch is so outstandingly unique a formation as to merit the adoption of stabilization methods.”

The general superintendent in Globe Arizona was delighted. “It is encouraging indeed,” he said, “to know that Mr. Miller is in accord with our view.” Although the NPS Advisory Board opposed the stabilization of geological formations in National parks, Davis insisted that Delicate Arch should be an exception. On December 22, 1952 he wrote:

“I believe we are all agreed that one use of our Parks and Monuments is as great outdoor museums and, as such, Arches National Monument has perhaps its most effective exhibit in Delicate Arch. To allow this unique formation to fall without making some effort to prolong its existence would be to lose forever an integral part of the story justifying the existence of Arches National Monument.”

Within months, memorandums no longer asked if the arch should be stabilized but “where and what method should be used.” By the spring of 1954, the memorandums were flying at a fever pitch. A meeting was proposed for March 3, 1954 and were to include representatives from the Engineering Division and the Landscape Architectural Division. They were to “discuss the stabilization of Delicate Arch and to make arrangements for the execution of the proposed work.”

And then came landscape architect David Van Pelt. Obviously not caught up in the stabilization fever that had affected others, Van Pelt met with Bates Wilson at Arches, discussed the question of stabilization and filed his report. He was the first to see that meddling with Mother Nature might very well backfire. “It should be realized,” he wrote, “that the wisdom and success of whatever action may or may not be taken to stabilize the arch can never be accurately appraised.”

Van Pelt proposed two alternatives:

1. To take no measures toward stabilization. This view arises not out of indifference nor apathy, but from a consideration of the uncertain benefits of stabilization, of the very real possibility that more harm than benefit may be done, and in the knowledge that Delicate Arch is “in extremis”, its collapse only deferred by the efforts of man.

The stabilization of ruins does not offer a precedent in the analysis of the weaknesses of the arch, nor in procedures for strengthening it. The collapse of ruins follows definite patterns according to their methods of construction, such methods being few in number and not fully understood. They are restored by proven techniques, based on known forces, strength of materials, etc.

A complete stabilization, using methods common to ruins stabilization, of Delicate Arch would involve uncertain results, not inconsiderable danger to arch and workmen, and great expense. The arch is in a relatively inaccessible location, to which all materials and equipment would have to be hauled by pack-animal or small tractor. It is poised on the edge of a deep canyon, necessitating extra safety precautions. No one can say that it would not partially or wholly collapse while work was in progress.

2. The contention that nothing should be done is prey to the equally defensible argument that, since the patient is doomed anyway, we are justified in making some attempt to prolong his life.

If the project was to proceed, the most efficient technique seemed to call for the spraying of the weak leg with a silicone epoxy. Another option, proposed by engineer J.R. Lasstic, was “to ring the weak point of the weaker leg with a concrete collar, making an attempt to color and form the concrete to blend as well as possible with the natural structure.”

Superintendent Davis in Globe, Arizona bubbled with enthusiasm. Despite Van Pelt’s warnings, Davis felt that “the trial use of a silicone preparation can certainly do no damage and it may well afford some protection from weathering.” The Regional office seemed to be in contact with every silicone manufacturer in the country requesting free samples. And Davis added, “I suggest that all of these be field tested at Arches.”

Meanwhile, the staff at Arches appeared to be hiding as best it could from the entire project. Arches superintendent Bates Wilson’s signature is conspicuously absent from all correspondence. General Superintendent Davis, concerned that the silicone had not been tested, inquired as to whether they needed more. A few weeks later, Davis sent another memo to Bates Wilson, asking him to estimate needed additional funds to complete the job. No reply from Arches. On October 13, 1954 the acting General Superintendent sent Bates one more memo. “Will you please,” he pleaded, “make a special report on this project at your very earliest convenience?”

Acting Arches Superintendent Bob Morris finally responded. Well, it seems they mixed the ethyl silicate solution back in February and it was supposed to be applied within 90 days. Now, with winter closing in, Morris asked Davis, “To get the proper results, should we not order a new mixture?”

A tense memo came back from Davis. Write the manufacturer, he suggested, if they thought the silicone had gone bad. “A tabulation of the dates of treatment and a complete record of your observations should be made and forwarded to this office.”

Arches appeared to have worn the general superintendent down. The memos petered out and the issue died for almost two years. Then in 1956 Mr. Cutler, a visitor to Arches, sent a letter to the NPS Director, concerned with preserving Delicate Arch “for millions yet unborn.” Incredibly, he suggested “that a clear, erosion-resistant material could be sprayed on.”

The Acting Regional Director, Harthon Bill replied to the letter and advised the concerned citizen of the March 1954 study. “This office,” Mr. Bill advised, “is not currently aware of the immediate status of the work at stabilizing Delicate Arch. We can, however, assure you that this is an active project and every effort is being made to slow down natural processes of weathering with the objective of lengthening the life of this natural feature to the greatest possible extent.”

Finally, on April 27, 1956, Mr. Cutla received another letter from the Park Service Regional office. “During a recent visit to this office,” the letter stated, “Superintendent Wilson stated that several of the chemicals had proven unsatisfactory, because exposure to the weather had caused them to turn white, or scale off, or both.” Wilson also felt that it would require “several more years of experimentation” before the process could be implemented on the arch.

With that, the idea finally collapsed. Bates Wilson, it appeared, simply outlasted the Regional bureaucrats. No one loved Delicate Arch more than Bates, but the idea of sealing silicone on it with an orchard sprayer never appealed to his common sense. He continued to worry about Delicate Arch, but not from the standpoint of its collapse. In a monthly report filed not long after the Cutler letter,

Bates wrote: “the increasing desire of fools to carve their names in public places has reached the highest level possible in Arches at Delicate Arch.”

Thirty five years later, the wind and the rain continue to sculpt the arch, picking away at it grain by grain, and idiots with big egos and no brains still come to the arch to scratch their names on it.

Continuity.

Jim Stiles is Founder and Co-Publisher of the Canyon Country Zephyr.

To read the PDF version of this article, click here.

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!

[…] Stiles detailed on his blog, he ended up tracking down an obscure document from the park’s file cabinets titled “The […]

[…] Stiles detailed on his weblog, he ended up monitoring down an obscure doc from the park’s file cupboards titled “The Delicate […]

[…] Stiles detailed on his weblog, he ended up monitoring down an obscure doc from the park’s file cupboards titled “The Delicate […]

[…] The bizarre plot was uncovered by park ranger Jim Stiles, who researched old memorabilia during the winter off-season and published his findings on his blog, the Canyon Country Zephyr. […]

[…] The Stabilization of Delicate Arch – Ranger Jim Stiles’ article on his findings […]

Incredibly, he suggested “that a clear, erosion-resistant material could be sprayed on.”

“….there have been some, even in the Park Service, who advocate spraying Delicate Arch with a fixative of some sort — Elmer’s Glue perhaps or Lady Clairol Spray-Net.”

-E. Abbey

We don’t have to guess at whether Abbey was aware of this cockamamie scheme. That’s for sure.