One frenzied afternoon in Moab, more than 20 years ago, the crush of tourists, the asphalt-enhanced desert heat, and the already disturbing first hints of a “New West” future driven by an ‘amenities economy” got the better of me. I loaded the car, grabbed my camping gear and scurried out of town as fast as my ‘63 Volvo would carry me. I drove north to Crescent Junction and paused for reflection. I needed a change of scenery.

Left or right? I couldn’t decide. Maybe north to Jackson, I considered, but the tourist onslaught up there made our own invasion look mild. And then there was all that damn traffic. Or I could go west to the basin and range country, to the emptiness of eastern Nevada.

But as I stared at the map, I felt irresistibly drawn by the call of the prairie—the high plains of eastern Colorado and west Kansas. The thought of that vast wide-open country appealed to me on some level I couldn’t explain. I’d always loved the lonely expanse of the plains, the domed sky with its magnificent late afternoon thunderheads. I loved its remoteness.

For me, the prairie has never been, as it is for most, a place to simply get through–to endure–on the way to someplace else. I decided to find a quiet corner and linger for a while. And so I spent a week wandering its straight-arrow back roads and appreciating its limitless views and unpredictable weather and its sun-bleached history of abandoned farms and rusted out tractors and broken dreams. I’ve come back again and again, to the place so many want to avoid. Maybe that’s what appeals to me.

It’s a hard place to live or at least it used to be. Maybe the difference between Great Plains residents and the rest of the country is that they still remember how tough Life could be. As a result, they bear a deep respect for its fragile and temperamental nature–even its violent unforgiving side. They seem to take it in stoic stride.

This year’s weather has been brutal, from coast to coast. From the tornados in Alabama and Missouri, to the floods along the Ohio, Mississippi and Missouri Rivers, to record setting temperatures across two-thirds of the nation. On the plains, drought and unrelenting heat have persisted for months. Crops are in jeopardy of being lost, cattle are dying, but you’d be hard pressed to find someone complaining about it. They all remember the Dust Bowl or stories about those “worst hard times,” passed down from generation to generation. Whatever we are suffering through now, with the heat and the tornados and the flooding, most people of the Plains know that, no matter how bad it gets, it’s nothing compared to what it once was.

One day last summer, we were headed to the plains on a blistering hot July day. On the way, the air conditioning quit on my car, but we pushed on, somehow tolerating the 100+ degree weather. By the second day, the heat was intense but luckily, we found a mechanic in Clayton, New Mexico who quickly spotted the problem. Lorenzo replaced the belt in 30 minutes and we were on our way again. Now we could once again appreciate the grandeur of the prairie from inside our little all-wheel-drive, air cooled cocoon.

We were exploring back roads on the High Plains, looking for nothing in particular, when Tonya said, “Turn right up here; let’s see where it goes.” The road shrank to two tracks and meandered a bit over a dry creek bed and into the sunburnt prairie. We followed it, just as the sun was starting to set. At 9 PM, it was still over 95 degrees.

We found a cemetery. Although we were miles from nowhere, it was still being cared for. A fence kept out the cattle and what passed for grass had been recently mowed. As we wandered among the gravestones, we were hard pressed to find anyone who had been buried here more recently than 40 years ago. Yet somebody still remembered this place enough to maintain it.

Like all cemeteries, the markers told us a story. We came to recognize the prominent families, both by the number of stones and the quality of the monuments. Even now, it was clear to see who were the ‘haves’ and the ‘have nots.’ We could see who had managed to live long enough to become the patriarchs and matriarchs and whose lives had been cut short.

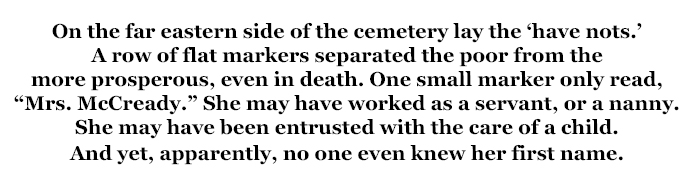

On the far eastern side of the cemetery lay the ‘have nots.’ A row of flat markers separated the poor from the more prosperous, even in death. One small marker only read, “Mrs. McCready.” She may have worked as a servant, or a nanny. She may have been entrusted with the care of a child. And yet, apparently, no one even knew her first name.

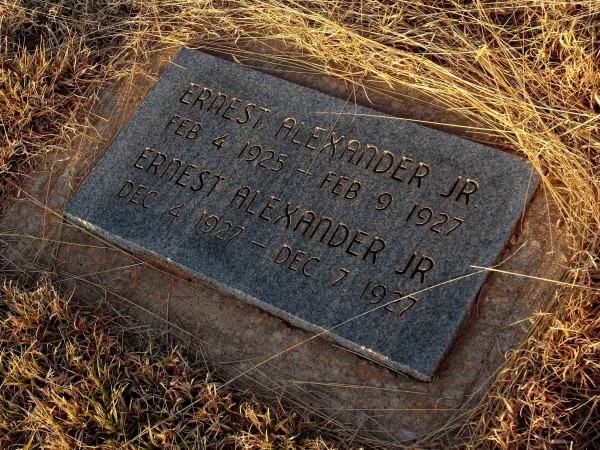

And we found many children’s graves. One small marker was especially moving. It said:

ERNEST ALEXANDER, JR

FEB. 4, 1925 – FEB. 9, 1927

ERNEST ALEXANDER, JR.

DEC. 4, 1927 – DEC. 7, 1927

At first we were puzzled by the two shared names. But then, as we examined the dates more closely, it became painfully apparent what had happened. Ernest Alexander and his wife had given birth to young Ernest, Jr. during the cold winter of 1925. He had only managed to live two years and the Alexanders had buried their infant son out here on this wide lonely plain. Barely a month later, Mrs. Alexander became pregnant again. She gave birth to another son on December 4, 1927, and they named him Ernest Jr. as well. He lived three days. He was buried beside his brother and a common stone was placed over them both.

We searched in vain for the gravestones of the parents but could find neither–perhaps the pain of losing two sons in ten months was more than they could endure and they left the country. I guess we will never know.

As we walked through the dry grass and closed the cemetery gate, we could barely imagine the hardships these people had endured; the land still looks much as it did then, but to imagine living there without the conveniences of the 21st Century, when we were truly honest with ourselves, was a sobering proposition.

Many of us talk about getting “back to the Land,” or of living a pastoral life we seek only for its gentle simplicity. We refer to ‘wilderness’ in such poetic, grand terms, but we never fully appreciate the brutal unforgiving wildness—the nature of Nature— and the burdens and hardships and tragedies our ancestors faced and accepted along the way.

I remember the lines from T.K. Whipple. He wrote:

“Our forefathers had civilization inside themselves, the wild outside. We live in the civilization they created, but within us the wilderness still lingers. What they dreamed, we live, and what they lived, we dream.”

We turned back onto the main gravel road, cranked up the air conditioning, and headed north.

Jim Stiles is Founder and Co-Publisher of the Canyon Country Zephyr.

To read the PDF version of this article, click here.

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

Don’t forget about the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!

It is said, “You didn’t build that”. But the farmers of the great plains did build it with dirt and sweat.

Your story brings to mind a small plot on a private ranch up in the Old LaSal area. There was, in 1963, a plain fence around those graves, (Dad built it.) and we planted blooming cactus over the little group. I thought it was a strange tribute, but Dad planned to leave Utah and go to Oregon, and as he said…Cactus would discourage critters, and still bring beauty to the wee plot where his sisters were laid to rest. One sister, Isabel, was just four when the Small Pox killed her. The other, Lacy, was a grown woman…and her babies were laid beside her. My Dad took us up every Memorial Day until he left for Oregon. The graves are still there, Cousins, have noticed the graves…and wondered to whom they belonged. The ranch is called The Company Ranch. My Grandparents worked there, George M. Stocks was a cowboy for them, and Grandma Susie Scharf Stocks cooked and mid-wifed there, in the early nineteen hundreds.