THANKS to Tom McCourt & the Tibbetts Family.

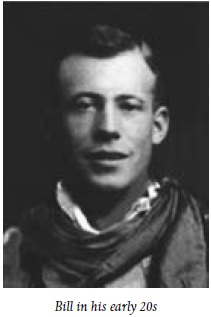

For years, I have been watching Moab move farther and farther away from its roots, to the point where it seems few people even know the history of the place anymore. Some of them don’t know OR care, but I think there are still many who have a respect for the past (I hope so, at least).Last winter I read Tom McCourt’s book on Bill Tibbetts and think it’s his finest work. I knew a bit about Bill, but the story was told so beautifully and I felt it was a very moving tribute, not just to Bill, but to those far off times.I see Moab as some alien world now, and I feel the most significant contribution I can make with the Zephyr these days, is to try and preserve the past in some fashion, or at least make it available for those readers who are interested. With Tom’s permission, the Canyonlands Natural History Association who published it, and with the good wishes and approval of Bill Tibbetts’ son Ray and the Tibbetts Family, we are pleased and honored to offer, over the next few months, excerpts from Tom’s excellent portrayal of ‘the Last Robbers Roost Outlaw.” JS

but the story was told so beautifully and I felt it was a very moving tribute, not just to Bill, but to those far off times.I see Moab as some alien world now, and I feel the most significant contribution I can make with the Zephyr these days, is to try and preserve the past in some fashion, or at least make it available for those readers who are interested. With Tom’s permission, the Canyonlands Natural History Association who published it, and with the good wishes and approval of Bill Tibbetts’ son Ray and the Tibbetts Family, we are pleased and honored to offer, over the next few months, excerpts from Tom’s excellent portrayal of ‘the Last Robbers Roost Outlaw.” JS

CHAPTER 7

Making a New Start

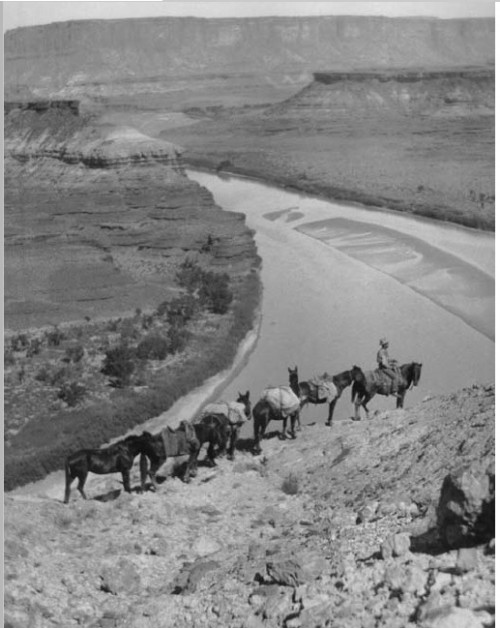

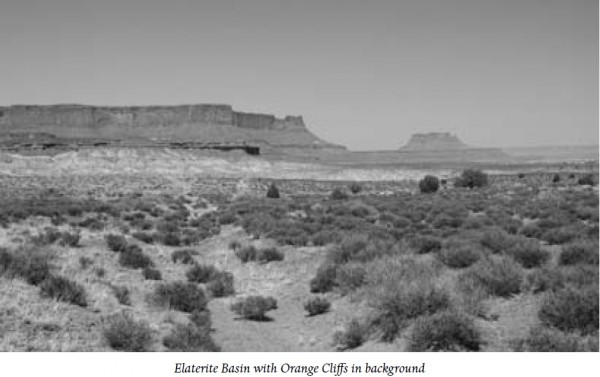

Bill Tibbetts and Ephraim Moore stepped down from their horses and stood looking south down the gaping canyons of the Green River channel. They were high on a rim in the land between the rivers, about twenty miles west of Moab.

“What do you think?” Ephraim said with a wry smile as he took off his hat and mopped his brow with an old red bandana. The July sun was hot and heat shimmers danced above the rocks, partly obscuring the 100-mile view down the river. The land before them was a tangle of deep canyons and high sandstone rims.

“Damn,” Bill responded quietly, “It’s rougher than I remember; hotter, too.”

“Well, we ain’t there yet.” Ephraim said with another smile. “I’ll bet the grass is taller than your stirrups down there someplace, and I don’t think anyone else has been desperate enough to try to run cows in such a rough damn place.”

“Well, I’m purdy desperate, all right,” Bill said with a smile of his own. “I just hope these crowbait old horses of yours’ll get us in and out of there. I’d sure hate to walk home.”

“You better make friends with that cranky old pack mule then,” Eph said smugly, trying not to smile. “If your mount gives out, you ain’t gettin’ mine.”

Both men laughed, remounted their trusty steeds and turned north toward Mineral Canyon and the top of the Horsethief Trail. Bill was only kidding about the horses being crowbaits. Ephraim owned some good horses. He just felt bad that he had to borrow one. He didn’t own a horse of his own yet and he would have to fix that soon.

The Horsethief Trail took them off the high mesa to the Green River. From there they set out to explore the country to the south.

For a couple of weeks Bill and Ephraim searched the rims and river bottoms south and west of Island in the Sky. They went forty or fifty miles down the river, checking the canyons and the ridges between the canyons, searching for grass and water. It was rough damn country, as Ephraim had suggested that it would be, with lots of sand and sandstone, scrub cedar, cactus and sage. They found no hidden valleys with thick carpets of grass like they had hoped for, but there was enough feed scattered in the rocks and on the hillsides to support a respectable herd if the cattle were spread over a wide area. And there was a little water there, too. The canyons had dry washes and not flowing steams of water, but there were a few springs in the sandy bottoms that could be developed and used. Most of the water was high in alkali content, but good enough for livestock. They found a few natural tanks in the slickrock that could be used by cattle, as well.

They found the country empty, but there were signs that someone had recently been there. There were a few old tracks suggesting that some stock, probably sheep, had been pastured there during the last winter. But there were no stockmen to challenge their right to be there, and no other man’s cows eating the summer grass … as yet. As far as they could tell, they had found a virgin territory unclaimed by any of the big cow outfits.

Bill and Ephraim were excited. They hurried back to Moab to make their final plans. They would gather what stock they could from the White Rim and from Bill’s mother’s place to put together a herd to take to their new range as soon as possible. They had to take possession before another stockman moved in on the land they had found. But first, Bill had to buy some horses.

The dusty cowboys arrived back in Moab on the 23rd of July, just one day before the town’s big Pioneer Day celebration. The 24th of July was the day the first Mormon pioneers had entered the Salt Lake Valley back in 1847, and every year the event was celebrated with religious zeal all over the state of Utah. The boys found Moab crowded with people and there was a carnival atmosphere on the streets. Tomorrow there would be a big parade down Main Street, a horse race or two, a baseball game, a picnic in the park and a big dance in the evening. It was the most celebrated holiday of the year and people were flocking to town from all over the area, wearing their Sunday best.

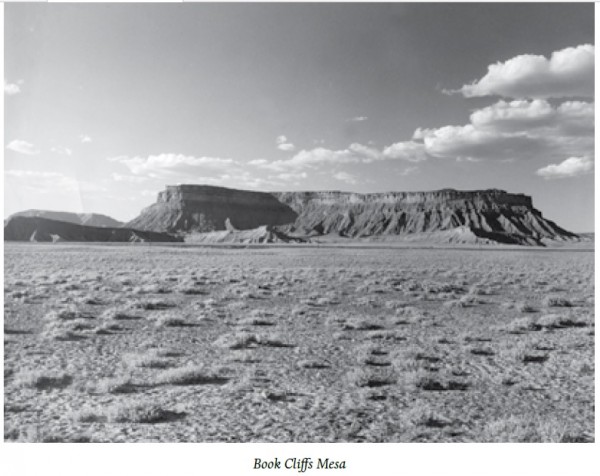

Bill’s uncle, Will Moore, had come to town for a few days to enjoy the festivities, and Bill was excited. The young man hadn’t seen his favorite uncle for a long time. More important than that, the older cowboy worked for one of the big cow outfits on the Book Cliffs and he might know where to get some good horses.

Everyone in Moab knew Will Moore. He was famous in eastern Utah because he had a wooden leg like a pirate. Most people knew him as “Peg Leg Moore.” Actually, the leg was made of cork instead of wood, and it was only his foot and not his whole leg that was missing, but the man walked like a penguin in a stiff, shuffling gate that made him stand out in a crowd. When he went to town, little kids came running to get a good look at the big cowboy with the wooden stump for a leg.

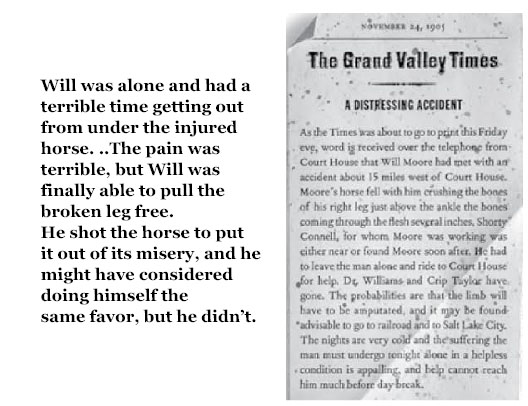

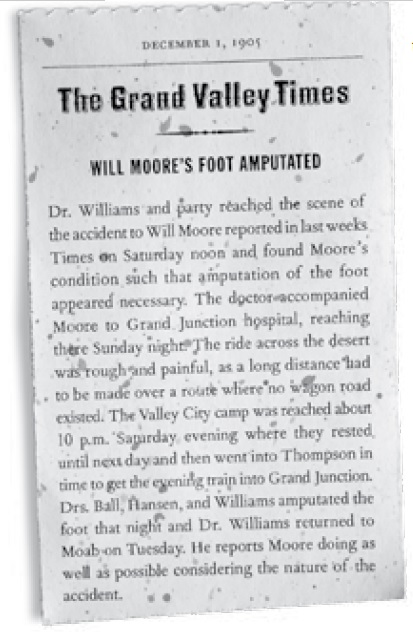

Will had lost his leg in November 1905, while herding cows in the Dubinky Wash area, about twenty miles northwest of Moab. He was working for a man named Shorty Connell at the time. The ground was covered with snow and Will was chasing after a steer when his horse stepped in a badger hole while running full tilt. The horse broke its leg and came crashing down on top of Will, who was pinned beneath the animal with his foot twisted back and his toes pointed in the wrong direction. When the horse came down on his foot like that, it shattered Will’s ankle and pushed a splinter of bone through the skin “several inches,” according to the Moab newspaper.

Will was alone and had a terrible time getting out from under the injured horse. He would kick the animal in the face with his uninjured foot to make it rise up just a little, and each time he would try to pull the broken leg a little further out from under the floundering beast. The pain was terrible, but Will was finally able to pull the broken leg free. He shot the horse to put it out of its misery, and he might have considered doing himself the same favor, but he didn’t.

The man was alone with the shattered leg, bleeding, in shock, on the ground and in the snow. He couldn’t walk and there was nothing to ride. He was at least a mile from the cow camp and about fifteen miles from the nearest settlement at Courthouse Station. But, like the trooper he was, Will started to crawl on his hands and knees through the snow. He left a trail of blood and a strange furrow in the snow that was the drag mark of the broken bone sticking out through his torn boot. The cold and snow might have saved him from bleeding to death by helping the wound to clot.

Luckily, when Will didn’t show up at the cow camp by late that afternoon, his boss, Shorty Connell, went looking for him and found him crawling in the snow toward camp. Will had lost a lot of blood and he was almost frozen to death. He had shot all of his bullets trying to attract someone’s attention. Shorty took Will to camp and made him as comfortable as possible, then rode to Courthouse Station to summon help. Will had to stay all night in a tent without medication or anyone to attend to his needs or keep a fire going. It took eighteen hours for Shorty Connell to summon the doctor from Moab and return to the cold tent where Will was waiting.

Over the next two days, Dr. Williams treated the injured man while he was transported to Thompson Springs in an open buckboard. The rescue party took the shortest possible route, breaking trail through the rocks and sagebrush where no road existed. Buckboards were appropriately named. They had iron-rimmed wooden wheels mounted on axles that were bolted directly to the wagon box without any springs. The trip was absolute torture for a man with a compound fracture.

The rescue party and their patient stayed the first night at a place called Valley City, about twelve miles southwest of Thompson Springs. When they reached Thompson Springs on the afternoon of the second day, Will was put on a train and taken to a hospital in Grand Junction, Colorado, where his foot was amputated.

The rescue party and their patient stayed the first night at a place called Valley City, about twelve miles southwest of Thompson Springs. When they reached Thompson Springs on the afternoon of the second day, Will was put on a train and taken to a hospital in Grand Junction, Colorado, where his foot was amputated.

It was a bitter pill to lose a foot, but, as a tough and practical man like Will Moore might have said, his foot was a long ways from his heart, so things could have been worse. Just a few months later, Will was back to herding cows. He simply wired a tin can to his right stirrup, and with his stump tucked firmly in the can, it was hard to tell he was a one-legged cowboy—unless he got off his horse, of course.

~~~

In Moab, on the 24th of July 1919, Bill Tibbetts was happy to see his peg-legged uncle. After the usual handshakes, back slaps, and bear hugs, the men got down to business over a foaming brew at the Moab pool hall. Except for Uncle Ephraim, of course. Ephraim was a better Mormon than the other two and adhered more strictly to the church’s ban on alcohol, coffee, tea, and tobacco.

“I’m goin’ in the cow business with Eph and I need some good horses,” Bill said as he leaned forward over his beer mug so Will could better hear him over the din of the holiday crowd in the pool hall. “I’m talkin’ about all-day horses, sixty-mile horses, horses that can cross that desert and not give out. We’re crossin’ the river to the Laterite country over near Hanksville and we gotta have some good mounts.”

“You got pockets full of money?” Will asked with an amused smile.

“No, I ain’t got much, and you know it,” Bill said, becoming somewhat impatient with the older man. “But I thought maybe you could help me out. You know, maybe you got connections with one of the big outfits and could help me swing a deal or somethin’.”

“Actually, you came to the right man,” Will said very business-like. “I do know where you can get some good horses. And they won’t cost you all that much, either. I’m in good with a band of Utes up on the White River country near Vernal, and they got just what you need.”

“Indian ponies? Are you out of your mind?”

“They might not look as dandy as some of the horses you high-classed cowboys are used to,” Will said with a sarcastic, half-drunken smile. “But they’re tougher than boiled owl and more sure-footed than mountain goats. And they can go all day without a drink of water, too. Those horses run wild in the Book Cliff country when they’re colts, and there ain’t a better animal anywhere for workin’ the rough country.”

“Aw, I don’t know, Will. Most Indian ponies I ever saw were almost starved to death.”

“Those Northern Utes don’t keep runted ponies like some of the other Indian tribes,” Will promised. “They raise some good horses over on the Uintah Reservation. You’ll have to see ‘em to believe it.”

Bill, Ephraim, and Uncle Will left for the Book Cliffs just two days later. Before they started out, Will gave them a lesson in the art of trading with the Indians.

“Those Utes are slowly learnin’ the value of the white man’s money,” he said. “But when they trade horses, they gotta get somethin’ of substance to show they made a good trade. If you go there to trade and take only money, they’re gonna want whole big handfuls of the stuff to make it look like they got a good deal. So what you do is buy goods before you go, and then trade the goods for the horses instead of dealin’ in money. I know it sounds crazy, but that’s how it works. Twenty dollars’ worth of blankets and calico, tin-ware, sugar, coffee, and such, will buy you a good sixty-dollar horse. If you go there with only money, that Indian is gonna want a hundred greenbacks for that same sixty-dollar horse. That’s how it works. You can pay twenty dollars in goods or a hundred dollars in cash for the same animal. It all depends on how you trade.”

For his first venture in the art of Indian trading, Bill took one of Ephraim’s pack mules loaded with about forty dollars’ worth of trade goods. A few miles from the town of Ouray, Will introduced Bill and Eph to his Ute friends and the Indians took them out to the horse pastures. Bill could see right off that Uncle Will had been right. The Utes had some fine looking horses. Bill was excited.

To the Indians, horse-trading was sport as well as economics, and Bill got caught up in the spirit of the thing. It was great fun. For most of the day he haggled, bargained, postured, and pouted. Will and Ephraim were greatly amused.

Finally, late in the afternoon, after softening up his trading opponents with a good campfire meal, hot coffee, and cigars, Bill traded his goods for three fine horses. The Indians were happy. Bill was happy, too.

Back in Moab, Bill gave one of the horses to his stepbrother, Kenny Allred. Ken was just a little kid who looked up to Bill and wanted to be just like him. Bill promised to help Kenny be a cowboy when he grew up, just like his uncles Will and Ephraim had done for him when he was a kid. The gift horse was a pinto, a fine looking animal with black and white spots that any Indian or aspiring young cowboy would be proud to ride. That fancy horse made Kenny Allred the most envied kid in Moab.

Bill’s favorite horse to come out of his Indian trading adventure was a big bay gelding he named Ute. The big horse was the toughest and most reliable cowpony Bill Tibbetts ever owned, and he was a pleasure to ride. The Indians had trained old Ute, and like all good Indian horses, he could be mounted from either side, unlike most cowboy mounts that could only be approached from the left. The horse could also be guided Indian style by the rider’s knees without the use of a bridle, and he had been taught impeccable manners. He didn’t kick, he didn’t bite, and he stood still while a man climbed aboard.

Bill and Ute developed a special bond of trust and confidence in one another. Ute would go wherever Bill pointed him, and Bill always took care of the horse’s needs before his own. The two would spend many years and many thousands of miles together on the deserts and cattle ranges of southeastern Utah. Bill talked fondly about old Ute for the rest of his life. There was no other horse quite like him.

The young man took the rest of his savings and bought a few cows. It was a meager start for an ambitious young rancher, but it was the best he could do at the time. He also took Ute over to Brown’s Hole and gathered all of his mother’s cows he could find. Eph gathered most of his cows on the White Rim and bought a few more from some people from Texas who were selling out and going home. When Bill and Eph were ready and the pack mules loaded, they began their cattle drive to their new range on the Laterite country to the south. Elaterite Basin was the proper name of the place, but the Moab boys usually dropped the “E” and pronounced the name as “Laterite.”

~~~

It was fall when they reached Elaterite Basin with the cows. The cottonwoods were yellow and the sun was dropping lower to the south with each passing day. The nights were cold but the days still pleasantly warm in the shelter of the ledges.

They were scattering their cows in the grassy pockets among the rocks and rims, preparing to settle in for the winter, when they came upon another man’s cow camp. They were surprised and very disappointed to find it. There might be trouble if another outfit was claiming the range. They stopped and checked their guns, just in case. They never knew who or what situation they might be riding into out in the wilderness like that. The sheriff and the lawyers were a long, long ways away.

The enemy camp was at the north end of Waterhole Flat, a little south of Elaterite Basin. As Bill and Ephraim approached, they could see several horses tied to pinyon trees near a couple of big tents. Small groups of cattle were grazing in the background. As they got closer, they could see men standing around a campfire while another man was poking inside a big Dutch oven with a long, wooden spoon.

Cautiously, Bill and Ephraim rode toward the camp. Ephraim was the older man so he did all of the talking. From near 100 yards out, he shouted, “Hello there, we are entering your camp. We come as friends.”

The cowboys gathered around the campfire were surprised to see the men from Moab, but they were true to the Western code of hospitality and invited them down for beans, cornbread, and coffee. Everyone was impeccably polite, but tension hung heavy in the air. There were six or eight cowboys in the camp, but most of them were teenaged boys.

The boss of the outfit came out of a tent when summoned, and extended his hand cautiously in a sign of friendship. “My name is Lou Chaffin,” he said. “We’re from over by Torrey. Got a place on the Fremont River.” He was a man in his mid-forties, a reformed gold miner making a new start in the cattle business. Chaffin knew the area well, much better than Bill and Ephraim. He had placer-mined for gold on the Colorado River for years and had crossed this country many times before.

At first the boys from Moab didn’t quite know what to make of this intrusion on their newfound grazing land. But Mr. Chaffin had a good eye and he was civil. Things could have been much worse. It surprised them that the man was willing to shake hands and offer part of his own supper to a couple of rivals from across the river. It was a hopeful beginning. Bill and Ephraim introduced themselves and then sat at the other man’s fire and shared his evening meal.

“We thought we was goin’ to be all alone down here this winter,” Ephraim said as he chewed on a chunk of overcooked cornbread.

“Us, too,” Lou Chaffin offered. “We didn’t expect anybody to be here, other than those French sheepmen, maybe. They come here under the ledge almost every winter now. It’s a good place to winter sheep. They take those woolies back on the mountains in the spring. It gives the grass all summer to grow back, like it is now.”

“Under the what?” Ephraim asked.

“Under the ledge,” Chaffin answered, somewhat surprised. “That’s where we are now. Under the Ledge.”

“I thought this was the Laterite country,” Ephraim said.

“It’s called Elaterite Basin just north of here,” Chaffin explained, “but it’s all Under the Ledge. That’s the ledge over there,” he said, pointing to the towering shadow of the Orange Cliffs to the west.

The Orange Cliffs, also known as The Big Ledge, span almost forty miles along the western edge of the Green River basin. Near Elaterite Basin, The Big Ledge is over 1000 feet high and an intimidating barrier to travelers.

“Well, maybe you men from Torrey came down under that ledge, but me and Bill here, we crossed the river from Moab. We ain’t come down under that ledge yet. I think we’ll just keep callin’ it the Laterite country.”

“That makes a good point,” Chaffin admitted, careful not to smile, afraid the other man might take offense.

“So how we gonna split this range?” Ephraim asked, getting down to business. “We got a herd just north of here, in that E-Laterite basin you talked about.”

“Well, since we’re both new here, and neither of us seems to have a prior claim, I guess it’s up to us how we divide the grass,” Chaffin said.

There was silence around the campfire for a while, and then Chaffin spoke. “Tell you what, since you men are already in the Big Water Wash country over in Elaterite, I’ll keep my cows south of here in Waterhole Flat. We’ll let this area here be our buffer for now. You keep your stock north of here and I’ll keep my stock south of here. Does that sound fair enough?”

“How does that sound to you, Bill?” Ephraim asked.

“Sounds good to me.”

Ephraim extended his hand toward Chaffin for a handshake. “You got a deal, Mr. Chaffin. We’ll keep our stock in the Laterite country.”

On the way back to their own camp in the chilly moonlight, Bill turned to Ephraim with a smile. “You cut a good deal with that man, Eph. We got half the range and we ain’t got enough cows to fill half of what we got.”

“That man don’t know how many cows we’ve got,” Ephraim grinned.

“And we don’t know how many cows he has, either,” Bill admitted.

“Yeah, but we’ll find out. And so will he. The important thing is, we got us a first-user’s right to run cows on this range. We got us a gentleman’s agreement with our neighbor, and we’ll fight anyone else who comes along. It looks like we’re in the cattle business, nephew. How does it feel to be a man of substance?”

All images from the book ‘LAST OF THE ROBBERS ROOST OUTLAWS: Moab’s BILL TIBBETTS’ …By Tom McCourt. Buy the book here.

Click Here to Read the Previous Installments…

To read the PDF version of this article, click here.

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!