“It came from out of nowhere.”

Things do, of course. Come out of nowhere. It’s Easter week. Tuesday morning, waking up, every channel is BREAKING NEWS. There’s been a Terrorist attack in Brussels. The airport and the subway system. You turn the channel and hear the screams of a child in the Zaventem airport over a black screen. The camera returns to the reporters, seated behind translucent desks, who queue up the next video. Panicked faces stream past the camera, covered in soot. Unintelligible yelling. Crying.

You watch even longer, feeling that it’s your duty to experience this trauma along with everyone else.

You notice one man racing through the chaotic scene, his carry-on bag clutched in his arms, and wonder what he’s holding on to. Does the bag contain his father’s prized fishing tackles, the last poem his mother wrote, or drawings by his kids—something that, in its loss, would compound his pain beyond what he already feels, as a survivor who has just run past all the bodies he could have been?

The man’s suit was once black. His hair, snowy with soot, was slicked into place. Is the bag just his standard business carry-on? Is he clinging so desperately to a change of clothes, a book he finished two days ago, a quart-sized plastic baggie of 3 oz allowable liquids? You place yourself in his shoes—why are you holding on? Have you forgotten what’s in your arms? Are you afraid of losing your laptop and its data? Do you hold on because that bag was packed yesterday, was the final thing you touched, back when the world made sense, and you were still delusionally yourself and intact? In your shock, does some part of you believes the bag can take you back there?

Or are you just afraid? Maybe you’re alone, in a country that isn’t yours, with no one to care that you’re alive, and you just need something to feel in your arms. Maybe you believe the bag is holding on to you, too.

After awhile, the news is just showing the same videos over and over again, and you get tired of the lack of information, and turn it off. The day proves to be sunny, warm, and windy. Too windy.

Mid-afternoon, the fire siren wails over the town. It’s the same siren they trigger for car accidents on the highway, or, at one sustained high note, for tornadoes, but the weather suggests a grass fire. And that’s what it is.

The local Police department doesn’t have much to post, normally, on Facebook. You’re surprised to see they’ve updated their page to announce that the volunteer firefighters are all headed to the nearby border with Oklahoma to fight an encroaching wildfire.

This seems normal enough, though. You hear every few days about a small grass fire popping up somewhere and they never seem to be a big worry.

But this fire keeps going. By nightfall, the plume of smoke stains the Eastern sky and the wind whips through the town, overturning trash bins and whistling around the windows. You hear more sirens.

The wind never dies down. The rain never falls. And the fire rages for six days.

By the second day, your county is a regional headline. A “State of Emergency.” Under the smoke, half the state of Kansas lives the day in perpetual dim twilight. The wind picks up litter and sticks and leaves, flinging them at you when you walk outside. The fire damage, reckoned in thousands of acres, counts higher and higher.

By the third day, the Department of Transportation begins opening roads behind the path of the monstrous fire, and, on the fourth day, you can drive through to run your errands. At first, everything looks the same. The road is the same road you’ve known. Until you reach the fire line.

Then blackness, like you’ve never seen. The ground, the trees, charred on either side of the road stretching on to each horizon. Your mind searches for an analogy. It’s like driving on the moon, or through an apocalypse, or through hell.

It’s the same drive you’ve taken a thousand times, but it’s through a foreign land. You drive for half an hour through unceasingly scorched earth, recoiling at each newly blackened vista.

When you first visited this place, six years ago, when you and your husband were deciding to move to this open, uncomplicated, flat country, the two of you had driven out to a dirt road on the county line and, looking out over the rolling prairie, you had watched the sunset and the fireflies waking up in the valley, twinkling among the tall grasses into the nightfall. But now you drive by that dirt road and the tall grasses are burned to the ground. The valley is filled with smoldering ash, which bleeds fresh smoke across the highway, and you’re frightened to think that a strong wind could set it ablaze again at any moment.

That fear settles over you, and you note small, festering fires around you, in fields and under trees. You drive through one black field after another, over blackened hills, until you finally cross over a creek and you come out the other side.

The hellscape recedes behind you. Before you, a winter wheat field gleams a deep green. Trees are budding out with fresh green leaves. Everything is green. You could cry, it’s so lovely.

budding out with fresh green leaves. Everything is green. You could cry, it’s so lovely.

You turn onto the Main Street of Sun City, KS and the first thing you see are the fire trucks lined up to get more water. Across the street, pickups crowd the entrance to the town’s one cafe, and you wonder how many belong to volunteer firefighters, on a short dinner break before they return to the front line of the blaze. On the way out of town is a small church, and the tiny dirt parking lot is full to bursting with cars. This is confusing for a moment, and then you realize. You almost laugh, though it isn’t funny. It’s just how timing works. Of course, you think.

It’s Good Friday.

————————–

One Good Friday, more than any other, stands out in my memory. I was young, maybe 7 or 8, and it was the first year I sat through and fully understood the Good Friday Mass. The church was dark, with only a single light illuminating the altar, which had been stripped of all its cloth and left bare. The priest wore Black, and we read through the story of Jesus’ death, with members of the congregation speaking in the voices of Jesus, Pontius Pilate and the various Disciples. I was a story-loving child, and I followed along in my hymnal as Jesus was betrayed and arrested. When Pontius Pilate brought Jesus out before the Temple, the assembled congregation played the role of the bloodthirsty crowd. Around me, anonymous in darkness, my friends and family yelled “Away with Him!” They yelled, “Kill him!” at the appointed moment, and I read ahead in the story to see who would object. I waited for some voice to rise above the melee. But that wasn’t in the script. I began to cry when I realized what was coming.

Through the dim light, some of the adults carried in a large plain wooden cross and planted it in front of the altar. They stood before the cross for a moment, and then kissed it. We sang a quiet hymn, and the congregation began to line up. I stood beside my parents, holding my mother’s hand, as we made our way down the aisle. She, having memorized the hymn, sang along as we walked.

As we approached the cross, it grew taller and hulked over me, ten times my height or more. Even in remembering, it brings a shiver of fright. My fantastical mind, still immersed in the story we had read, turned this cross into its original—a place of fear and death—and I dreaded the moment when I would be brought close to it.

My father touched the cross, and kissed it, and then turned. My mother let go of my hand and did the same. I stepped forward, alone. I reached out and brushed my fingers against the smooth wood. Then I put my mouth to it. Quickly. The cold stung my lips and, immediately, I turned and reached out for my parents.

————————–

Each Good Friday is spent deliberately in the presence of Death. Right up close to it. And that makes it a rare day in a modern life. While our ancestors spent their days immersed in the realities of disease and deprivation, we can largely go through life feeling that we have things under control. Our lives are an algorithm, in which the right nutrition and the right amount of exercise, the right “work-life balance” and checking-off of tasks, will produce a quality of life that rolls along quite nicely most of the time. Bad things only happen to people who aren’t trying hard enough. And death, when it happens to others, is pushed quickly out of our sight. We aren’t wallowers, we’re doers! Optimists! We “think positive” and drink the recommended 8 glasses of water, and so we are due our happiness.

But it only takes a disaster for that algorithm to fall to ruin. For all our well-laid plans to be laid bare as facades. Frauds. A thinly plastered veneer that crumbles to reveal the truth—that we aren’t in control. We were never in control.

Death. Terror. Destruction. They can arrive at any moment and burn all our world to cinders. Turn the place we once recognized into strange terrain.

And, when that happens, what are we left with?

I wonder how many of the people sitting in the pews of their Good Friday service had spent the two days prior watching their ranches burn—their homes and their animals threatened. How many had been spared when their neighbors hadn’t, and were ashamed for it. And how many had suffered a total loss. And I wondered how close, during that service, came the specter of Death into their minds.

I hoped that they had faith enough not to be afraid.

That, after all, is the only thing under our control. The only aspect of our lives that can’t be torched by fire or blown to shreds by explosives. Our faith. Whichever principles we hold that don’t alter with circumstances. The belief that the land will recover, healthier than before. That there will be joy again. A belief in God, or in a core Goodness among men. The softness of heart that, paradoxically, is a stronghold against despair. A belief in Mercy.

All we hear on the news is chaos. It’s all about fear, and anger, and vengeance. Politicians scream for blood, and tell us that we can destroy the darkness through targeted airstrikes and troop deployments. In our fear, we reach out to assert control. Lock down the internet. Search everyone’s phones. Patrol the neighborhoods of people who don’t look like us. We will destroy chaos with the force of our suppressive powers. And when it pops up again in a new spot, we will suppress it again. And again. And again.

But Chaos wears a new face with each challenge. It will always adapt, shifting with the winds, to strike any vulnerability. And it would have us constantly altering ourselves to follow it. To confront the darkness of the world, we have to accept Death. We have to sit with it, seeing its power to disassemble our reality, and then we have to solidify what remains. What always remains.

In the end, our only retaliation is our character.

Tonya Stiles is Co-Publisher of the Canyon Country Zephyr.

To read the PDF version of this article, click here.

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

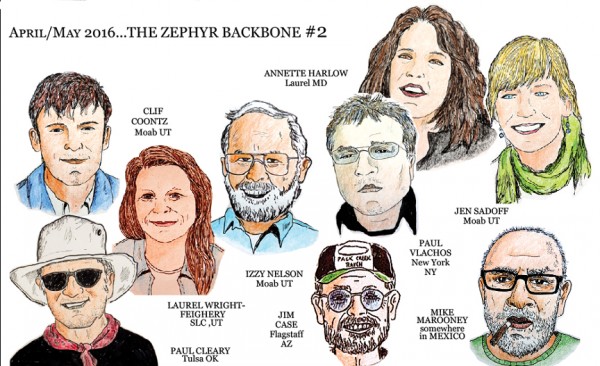

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!

The press is now saying the original plan was to attack a leaky rickety old Nuclear Power Plant in Belgium.

http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-3507417/Brussels-bombers-DID-plan-attack-nuclear-power-station-police-uncover-12-hours-footage-jihadists-filmed-outside-plant-director-s-home.html

Well said, Tonya. On a bright October day my wife and I had lunch together followed by a pleasant visit to Starbucks. Then, heading out to a hair appointment, she collapsed in the driveway and died.

For years I had worked to internalize the Buddhist teaching of impermanence, to take nothing for granted. I think that’s what got me through the whole thing.

Again, well said.

.