I drove past Glen Canyon Dam last week, on my way to visit friends in Springdale. It hasn’t changed much since my last visit, or my first for that matter; it’s still the biggest chunk of concrete I’ve ever laid eyes upon and it still floods one of the most beautiful sections of the Colorado River—Glen Canyon.

Of course, I’ve never really seen Glen Canyon in its pristine state. When the dam’s diversion gates

closed in 1963, I was still a kid in Kentucky, oblivious to these kinds of devastating man-made disasters.

Oh to be that innocent again.

My introduction to Lake Powell and its consequences came to me via an aunt I barely knew. Bertha Gunterman was a frail but feisty retired editor for Random House, living in New York, when she got wind of my interest in the West. She began sending me clippings from magazines about The Dam and the effect it was having both downstream in the Grand Canyon and, of course, the utter destruction by drowning upstream.

Early on, it had become apparent that this dam was a bad idea. For example, water released from the bottom of Glen Canyon Dam is cold—very cold—and consequently, it killed most of the native aquatic life  in the Grand Canyon. They’ve since stocked the river with trout, which is wonderful if you want to imagine you’re fishing an alpine stream.

in the Grand Canyon. They’ve since stocked the river with trout, which is wonderful if you want to imagine you’re fishing an alpine stream.

The dam had been built to “save” water for the Lower Basin states of the Colorado River Compact, but evaporation and bank storage was diverting millions of gallons of water away from the reservoir. That’s what happens when you build a reservoir in…the DESERT! The politicians could just as easily have moved the measuring point to Hoover Dam, 300 miles downstream, but that would have made too much sense and saved too much money. So the Bureau of Reclamation built another dam.

In my twenties, I became obsessed with The Dam and Glen Canyon. After my move to Utah, I made frequent trips to the reservoir and to Glen Canyon’s above-water remnants. I discovered Ed Abbey and read The Monkey Wrench Gang about 200 times. I dreamed of “the precision earthquake” that Abbey’s Seldom Seen prayed for. I drew a cartoon of The Dam with a gaping hole in its concrete facade and drove all the way to the remote Wolf Hole, Arizona to present it to my favorite author. Of course, Abbey didn’t live there as he’d claimed—he’d never even been there. Still my passion for Glen Canyon stayed red hot.

But one day, more than a decade ago, I was ranting about dam removal to an environmentalist pal of mine (an attorney of course) and I noticed a certain lack of enthusiasm on his part.

I said, “What’s wrong with you? Don’t you want to see Glen Canyon restored?”

He smiled sadly and replied, “It won’t be the same.”

It was true that the Glen Canyon Story went beyond the physical resource—there was a romance to it that elicited visions of a Desert Xanadu. Tucked away in this remote, unknown corner of the Southwest was an entire canyon system, almost 200 miles in length, and it was one of the best kept secrets in America. It truly was, as Eliot Porter later said, “The Place No One Knew.” It was full of history, going all the way back to the Anasazi. It was inhabited by just a handful of hermits and oddballs and explored by a strange mix of cowboys and prospectors and river runners. The legendary Bert Loper lived down in the Glen, in his old cabin that he called The Hermitage. Art Chaffin ran the ferry at Hite. The place was full of ghosts.

The men and women who had stumbled upon Glen Canyon in the 1940s and ‘50s, who really found religion of sorts here, were like an exclusive congregation. Their names, like Glen Canyon itself, are the stuff of legend. Glen Canyon will always be inextricably linked to the lucky few like Ken Sleight and Katie Lee and Harry Aleson and Moci Mac and Doc Marston. How much did this place mean to them? Watch Ken and Katie choke back tears a half century after the Glen’s demise. The loss runs deep.

“All that’s gone,” my friend said. “You can drain the reservoir but you can’t bring back the way it felt. That’s gone. All of it.”

He looked at me and said, “If they ever drain the lake, it’ll be a ZOO down there.”

Still, when the drought in the early 2000s pulled Lake Powell’s elevation down by 150 feet, I was anxious to see what the re-exposed parts of Glen Canyon would look like. Abbey had always insisted that Glen Canyon was not gone, that it was simply in “liquid storage,” waiting to be restored and rejuvenated.

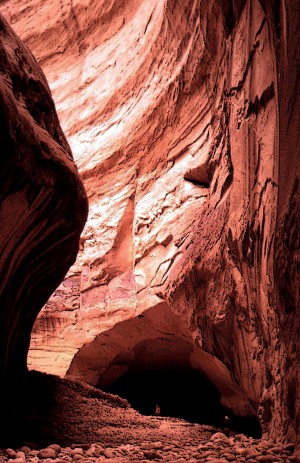

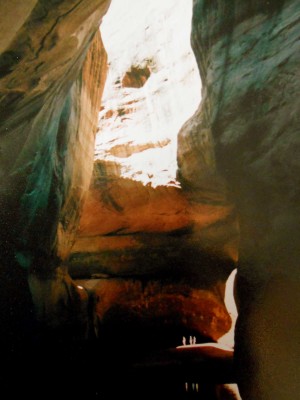

In March 2005, the reservoir fell to a level that, if my friend Rich Ingebretsen’s calculations were

correct, meant that one of the canyon’s most iconic natural features, Cathedral-in-the-Desert, was completely out of the water. Ingebretsen is the president and founder of the Glen Canyon Institute and is probably more dedicated than anyone to its restoration.

We’d seen the photos of this extraordinary side canyon, with its tapestried walls and hanging gardens and its fluted waterfall. What would it look like 42 years after it went under? Would it have retained its splendor after all these years? And would it feel the same? Ingebretsen and I wanted to find out.

To add some irony (or hypocrisy?) to our quest, we rented a speedboat to travel the 30 miles down lake from Bullfrog Marina—the very motorized contraption that we both claim to loathe. But we forgot about our contradictions when we found the Cathedral looking almost exactly as it had been portrayed in the old photos. Even small rocks on the ledges above the drop-off were just as they’d been in 1963. Later, we found inscriptions from the Hole-in-the-Rock Expedition, weathered but still readable after all these decades under water.

I’ll be damned, I thought. Cactus Ed was right—it IS still here in “liquid storage.”

Because we’d come down river in early March, we may have been the first visitors to see the re-emerging Cathedral. The ride back to Bullfrog was bitter cold and most people had the good sense to wait for warmer weather. And when the temperatures rose, the people arrived in droves. By May the narrow side channel was choked with tourists. Motorboats, house boats, canoes and kayaks—it was veritable gridlock down there. Scores of tourists rubbed elbows taking pictures and the silence we’d experienced in early Spring was gone, replaced by reverberating motors and the shouts and hollers of well-meaning admirers. It looked like Delicate Arch on Memorial Day weekend.

I wondered what Glen Canyon would be like if the reservoir were drained and the canyon restored. A free-flowing Colorado River would stop most of the house boats, but the river in Glen Canyon was serene and almost rapid-free. Motor boats were already making trips up and down the river in the last few years before the Colorado stopped flowing. They would surely return.

And what about the non-motorized traffic? I thought of the hundreds of thousands of 21st century recreationists who would descend upon this “secret place,” all of them looking to “re-create” the Glen Canyon that we’d read about. They’d be replacing the jet ski/Evinrude people, it’s true, and for some that’s an improvement, but it dawned on me:

Today’s noisy waterborne tourists recreate on top on Glen Canyon. Yes, they race about the lake at full-throttle and drink beer and make noise and disturb the general welfare, but the Glen is safe and sound under 500 feet of H2O.

Drain the lake and the New Generation of Glen Canyon Fun Hogs might make me nostalgic for water skiers. Instead of floating and boating over Hidden Passage, they’d be in it. The “place no one knew” would become “the place that got screwed.” It would, as we say too often now, be loved to death by the very people who claim they wanted to restore it. It’s an idea so common these days that the notion is a cliche.

The Park Service would naturally feel the need to control this mass, this mess of “adventurers,” and Glen Canyon Recreation Area would eventually become yet another heavily-regulated river––the waiting list for permits would stretch to years.

I thought about the way the spiritual and moral aspects of our last wild places have been pushed aside in favor of their recreational and commercial components. I wondered if the return of those magnificent thousand foot canyons would be seen for their grandeur or their climb-ability. Would these spires inspire? Or just challenge gonzo climbers to ‘conquer’ them? Would visitors to the Cathedral-in-the-Desert feel reverent? Or would they instead be inspired to exploit its beauty in some commercial way nobody has even fathomed yet?

A couple days later, returning home again via The Dam and Page, Arizona, I passed the overflowing parking lot for Antelope Canyon Scenic Tours. Twenty years ago, nobody had heard of this stunning slot canyon. Today its promoters are making the big bucks. It’s a real “wilderness adventure.” When I think about restoring Glen Canyon, I know that this is a harbinger of things to come.

And it occurred to me…maybe we don’t deserve the return of Glen Canyon. Not yet. Would its restoration be anything but a cash cow for the “amenities economy?” Would it simply be the latest natural wonder to be exploited by thousands of entrepreneurs and trampled by millions of insensitive, thrill-seeking recreationists?

After decades of longing desperately to see Glen Canyon out of the water, I surprised even myself when I thought: Maybe keeping it in “liquid storage” is the better alternative. Maybe it’s even safer down there under all that water. Because today, I’m not sure we humans are worthy of something as holy as ‘The Place No One Knew.’

Jim Stiles is Founder and Co-Publisher of the Canyon Country Zephyr.

To read the PDF version of this article, click here.

Yeah. Let Glen Canyon lie under the water. Humans are not ready yet.

Thank you for that article. Beautiful.

Nice reflections, Jim (river pun intended). I’d only add that there remain plenty of places no one knows. They’re just a little homelier than the Cathedral-In-The-Desert and sometimes they’re only a short walk from the numerous over-run jeep trails. This is why I’ve never been to Antelope Canyon or The Wave or Grand Gulch. Am I missing something? Just the crowds and the permits and the parking lots and the rules and regulations…. But I grant you, even in the homely non-marked less spectacular places I seek out, I have found rock art vandalized and Budweiser cans lying about. There’s only one way to escape the scourge of Homo sapiens completely and I’m not yet ready for the peace and quiet of the grave. Rock On (another pun intended).

It needs top be more dangerous, and lots hotter. Set up a sluice with a wave generator vaned run flash floods through the side canyons once every 2 hours. Or maybe on no schedule, irregularly and by surprise. That will add an element of adventure for the “adventurers.” (Or maybe block the canyon leading in to Rainbow or Cathedral or Music Temple, and force people to hike in overland if they want to see it. That’ll thin out the lazy ones–)

I agree with Evan. I’ve found other beautiful hideaways the crowd has not yet reached. I’d rather go there, and I’ll look at Eliot Porter’s photos meanwhile. It can happen. . . . no, really. . . .

Keep it like it was!

Sadly true Jim. I’d go, but I’d go in the Winter. I won’t do the Grand in Winter, but the Glen… yeah. I’d be happy to freeze my balls off for a one time run…. if I could get a permit that is.

Taking the Genie out of the bottle, and letting nature (finally) settle the game? I’m a member of Glen Canyon Institute and in my heart, wish the dam would come down and that heavy rains and floods would then scour out the myriad of canyons so the place could finally “breathe free.” But then, years of canyoneering, desert trekking and traveling in Glen Canyon have opened my eyes to the fact that too many view Glen Canyon as a “resource to use” and that the intrinsic serenity and solace of the place would be totally lost to most. When the river was down “years back” I rapped some four drops and then peered into the cathedral – and then dropped in – as boats bellowed rap music below. The boater graffiti in the upper “cathedral” canyon was a defile of the sacred and it was reminder that many don’t equate the wonders of nature with holiness. If it ever is opened; poets, artists and shaman, should issue permits, to the worthy (?)

The romance of Glen Canyon is a faded dream of the past. The desert remains but care must be given or people with good intentions will love it to death.

What a thought…that liquid storage is preferable. But, you know, it is.

You can’t have a viable relationship with a wild area or for that matter with a human being until you learn to respect the limits that relationship places on you. It may sound strange to say it, but the overcrowding and misuse of sacred places on the one hand and domestic violence charges on the other stem from similar human deficits.

Good article.

I arrived in Utah in 1972. My first canyon experience in 74′ but sadly post dam.

I have always wanted that surgical earthquake to occur in my lifetime. And I still do. Given the

current situation at Lake Meade, global warming will likely dictate the ‘one reservoir’ outcome. As for the industrial tourism; it will be too damn Hot.