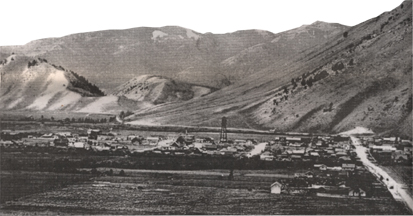

One summer a new fad took over Jackson Hole’s kid population, Bottle Horse Ranching. I’m not sure, but suspect that the ranch kids started it. We townies began regular roundups to the back lots of Jackson’s three saloons, picking up whiskey bottles — those were the cows (Herefords in those days), and beer bottles — those were the horses.

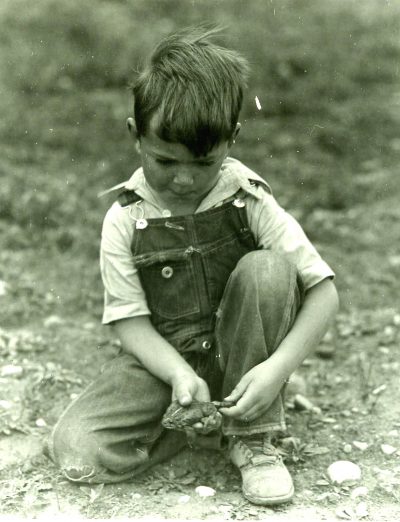

My brother and I set up our ranch at the dirt place, an oblong patch of pure, deep dirt on the east edge of our yard, next to a line of willows through which an irrigation creek gurgled past. Between the dirt place and the ditch, the land — overgrown with stray alfalfa, clover, grass, and other vegetation — rose slightly. We decided that the far side of the irrigation ditch was summer range. We used dead willow branches, broken into pieces to make buck fences around the home ranch’s pasture and hay fields. We used empty Log Cabin brand syrup cans as ranch headquarters, bunkhouse, et cetera.

As our herd grew we saw the need to get the stock onto summer range. Using hand-held beer bottle horses to push the whiskey bottle cattle, we started the drive. First, into the uplands bordering the irrigation ditch, now in full flow, a severe challenge. Could we herd the cattle across that river to higher ground just beyond? No hands allowed on the whiskey bottles, of course. Those critters had to be pushed by bottle horses. We tried it, cow by cow, each horse performing marvelous acrobatics, shouldering those cranky animals to the further shore. We succeeded. I don’t remember any of the cows breaking though we did lose a few downstream and counted that as normal loss in a wild range operation.

We did those drives more than once. I remember well the time I hazed my prize Hereford bull across those treacherous waters to a safe landing in cow paradise where he would ensure a superior lot of calves. He was a super-size Golden Wedding flask, embossed in color on his flank. He came from  behind the Log Cabin Club, the Cowboy Bar, or the other saloon whose name escapes me.

behind the Log Cabin Club, the Cowboy Bar, or the other saloon whose name escapes me.

One weekend a ranch kid stayed with me. We did a cattle drive. I had stayed a weekend with him at the ranch in Spring Gulch where we spent most of our time working on a high dirt bank, building little roads for his collection of miniature cars and trucks. The roads had switchbacks and huge gulfs of space spilled out below their unfenced edges. Hours went by. That was his dirt place. He loved vehicles. He wasn’t into the bottle horse craze and didn’t do much with flesh-and-blood horses either.

I think every girl and boy in Teton County had a choice of dirt places. If not in the back yard, then on the banks of Flat Creek or Cache Creek, or Fish Creek; or banks and flood plains of the Snake, the Gros Ventre, the Buffalo. We had dirt at the grade school, too; one big patch of it mixed with ash from the coal-fired furnace made an excellent playing field for marbles. A kid with a reliable taw and some snap to his thumb could rake them in. The rest of us played bumpers against the pale yellow bricks of the school. We carved holes in those bricks too. And snow melt time brought huge puddles that could be diverted, enlarged, joined, messed around with. And when spring came for good, warming the earth beneath the sage, there were Johnny Jump-ups, their yellow bell-shaped blossoms good to eat, and wild onions.

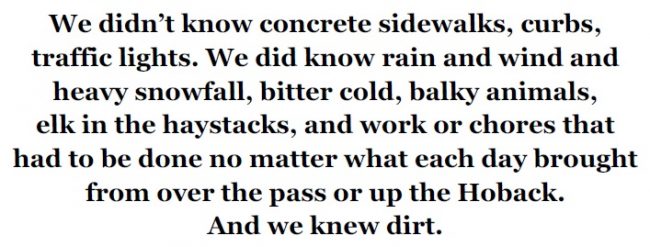

We didn’t know concrete sidewalks, curbs, traffic lights. We did know rain and wind and heavy snowfall, bitter cold, balky animals, elk in the haystacks, and work or chores that had to be done no matter what each day brought from over the pass or up the Hoback. And we knew dirt.

Whenever I pass one of those neat playgrounds attached to elementary schools or child care centers, noticing kids shouting to each other on the ladders, platforms, chutes and other adult-built structures, all neat and standard and based on hard blacktop, I think of dirt.

One of our daughters was pushed off one of those structures. Her head struck the blacktop; she suffered a skull fracture, lost consciousness. That was one godawful scary day. I don’t know how many kids are injured on institutional playing fields, but what I’d really like to know is how many kids have fun. I mean the deep kind that draws on all the powers inherent in young minds and bodies. We call it creativity. As adults we cherish creativity. What about our kids, channeled onto things built for them by unseen others?

There are often groomed lawns attached to playing fields. If dandelions grow there, it’s a good sign; if not, you have to be suspicious. Chemlawn? What poison molecules lurk there? Besides, lawns are not dirt. Kids can horseplay on lawns, but in dirt they can dig and shape things, on their own or in earnest negotiation with colleagues.

Split, Croatia, at a time when Yugoslavia was still a multi-cultured nation. Kids on packed dirt, in the center of the city. It was a huge empty space on one side of the main street, probably waiting for urban development. Meanwhile, groups of kids had taken it over. They weren’t shouting at each other — too busy for that. They were teams in action, in one place feeding a fire made of odd pieces of scrap, in another place metal and wood structures were underway, made of discarded stuff. Later, we got acquainted with one of those kids. His enthusiasm was catching, his life totally taken up with what was happening out there.

Further south, Dubrovnik, a newer section outside the bounds of the walled city, open ranges, two of which had been olive groves. Here too, kids have taken over. Hopscotch diagrams scratched in dirt, a marbles game underway. Other games in progress, mysteries to us North Americans.

I’m always on the lookout for dirt places. Dirt is important, I tell myself, not only for kids, but for all of us, especially in these times when most of us live in a dream inside a nation obsessed with scrubbed-clean decorum made out of products touted by corporate ads that interrupt ball games, intrude on cyberspace, clog up the works everywhere. There is no hiding place, no escape from the mania of upscale neatness, the insistence on lawns, Mister Clean in control. We are literally, not only figuratively, sentenced to uniformity and submission. We’ve even gotten into the habit of christening certain wildernesses pristine.

In real time and place, of course, wildernesses are not pristine, they feature vegetation in various degrees of rot and they are homes of animals who root in the dirt and get their noses dirty, and lots of other critters and features Mister Clean would love to get his hands on. Yes, I know that what we mean by pristine wilderness is the absence of human interference. The Wilderness Act’s term is untrammeled.

Wilderness purists sometimes go so far as to cringe at the thought of other humans being present while they imbibe a vast distancing from human foibles, faults, fraternity.

Pacific Creek, Teton County, Wyoming, my three daughters at work. Highway roar and the Tetons’ Cathedral Group looming in the southwest are remote, unattended background to those girls. Their hands are busy with sand, gravel, stone and water. I watch, enviously. I get down on my knees and gouge out a groove that diverts a small braid of water to another braid. The sun is low in the west, warm on our hands.

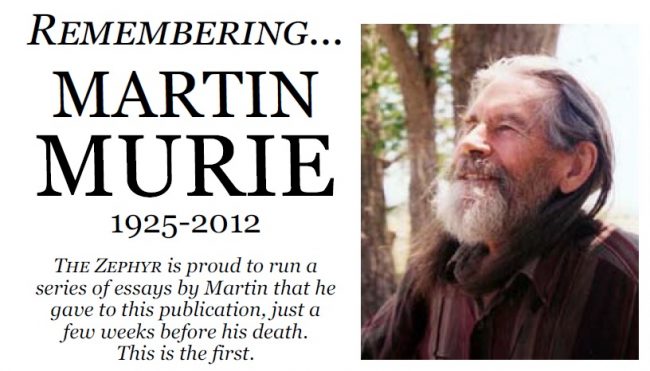

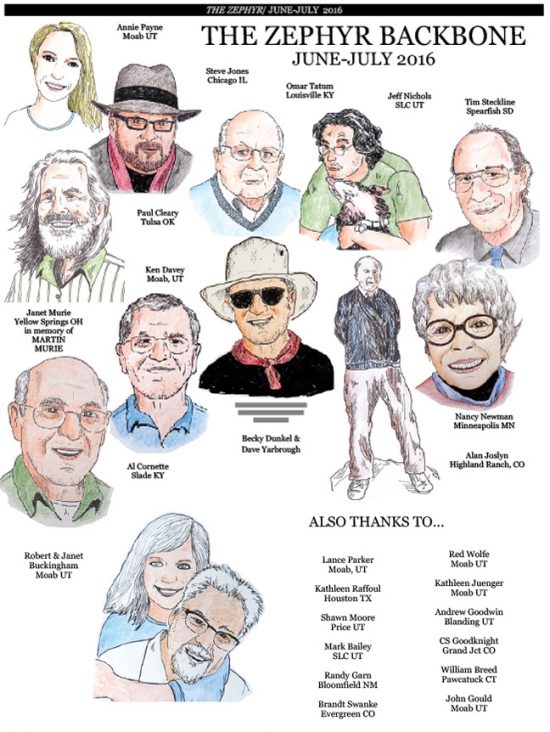

Our dear friend Martin Murie died in 2012.

To read the PDF version of this article, click here.

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!

Mr. Murie’s essay might be one of the best things I’ve read this month. Thanks.