“The government is not in the business of taking care of the people or the land, the government is in the business of taking care of the government.”

I read this comment on The Friends of Canyon Country Zephyr page and it got me thinking. A lot.

I realize I would probably have very different perceptions and opinions about the role of government and public land issues had I been born and raised in Moab. I was raised in northwestern Massachusetts and the San Francisco Bay Area and was exposed to a lot of other places along the way. I had the privilege to travel a lot when I was a kid with my parents when my dad, a geologist for the USGS, was asked to work in various parts of the US and other countries for months at a time and was allowed to bring his family along. I have never viewed the US federal government as inherently against its own people. I was privileged to attend a high school where we were required to read primary sources as well as text books in history class, and I certainly learned a great deal about the US government’s poor behavior over the years as well as the inequality and oppression of so many other governments. Despite the poor behavior of some elected officials and agency staff, government has always seemed to be to be a necessary part of living in a stable community.

I admit that my bias is not to see government as inherently a bad thing, though I do view it to a large degree with a healthy dose of skepticism. I tend towards the belief that “democracy is the worst form of government, besides all the others” or however that quote goes (though I will admit the current election is giving me pause.) That said, I hear it often said in Moab and surrounding areas that the government (meaning the BLM, or the USFS) is bad and is over reaching. When I dig further to find out specifics about exactly how it is bad I hear general comments about taking away rights, and preventing people from doing things on public lands. It is all usually spoken in fairly broad terms – or tells only one side of the story. Or, as in the case of the new rules for camping and wood collection near Moab, I see the new rules as a needed means to cope with too many people in too small a space.

That isn’t to say some specific stories don’t give me pause, but I have yet to get much clearly articulated detailed descriptions of exactly what is being taken away or stepped on by “government overreach”. But I am searching (keeping in mind it is spring and the absolutely worst time of year for anyone involved in agriculture or plant growing to find time to read), and will continue to search to better understand this assertion. Through understanding perhaps I can better understand the frustration so many people in SE Utah seem to feel towards public land management.

I JUST WANT A FEW SEEDS…..

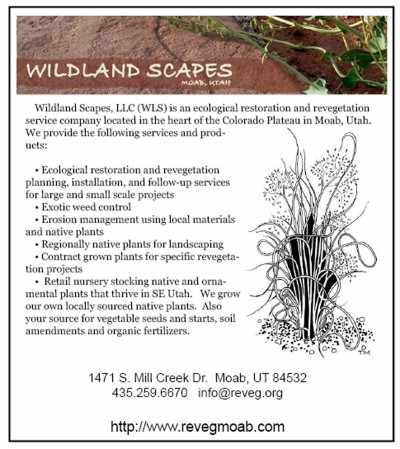

I have had my challenges working with the BLM here in Moab. I grow native plants for retail sale at our small nursery in Moab, and am especially interested in locally sourced plants. It took nearly 5 years to get a permit to collect small quantities of locally sourced seed to propagate. Since the seed collected  may ultimately be grown into plants that are sold there is a money generating aspect to my request, albeit a pretty tiny one, which kicks my permit request into the commercial category. It has been a frustrating process to be sure, though a tiny one in the context of the explosive growth in recreational use and permitted events and businesses in Moab. The irony of being unable to acquire a permit for a regenerative activity when others can go to the local office to ask for an event permit or a commercial permit to guide people on various tours that have the potential to impact more area and more plant material than I will ever grow from the small quantities of seed I want to collect made me quite frustrated. I couldn’t help but think if my request came from a larger business with an army of lawyers waiting to sue that I would have had my permit in short order. The permit is only good for one year, but my hope is that it can and will be renewed when I demonstrate the small impact this commercial activity has on public lands.

may ultimately be grown into plants that are sold there is a money generating aspect to my request, albeit a pretty tiny one, which kicks my permit request into the commercial category. It has been a frustrating process to be sure, though a tiny one in the context of the explosive growth in recreational use and permitted events and businesses in Moab. The irony of being unable to acquire a permit for a regenerative activity when others can go to the local office to ask for an event permit or a commercial permit to guide people on various tours that have the potential to impact more area and more plant material than I will ever grow from the small quantities of seed I want to collect made me quite frustrated. I couldn’t help but think if my request came from a larger business with an army of lawyers waiting to sue that I would have had my permit in short order. The permit is only good for one year, but my hope is that it can and will be renewed when I demonstrate the small impact this commercial activity has on public lands.

PARTNERSHIPS and COLLABORATIVE DECISION MAKING IS MESSY

I have lived in Moab (or within 20 miles of it) for nearly the last 25 years. I have been involved in issues and many projects focusing on areas of public land in SE and Central Utah for most of my time here. I have intentionally not sought employment with the federal government, not because the government is evil but rather because I saw first hand how frustrating it was for my father to work there in many ways, even though he had one of the best jobs imaginable. From time to time as I age, I wonder the wisdom of this choice – especially as I have chosen to grow native plants for a living, not exactly a high profit margin or secure profession….and then I hear from friends who do work in government agencies locally and I realize that that work environment is probably not for me.

So I have a healthy cynicism about the government, but I also have a respect for the challenge of managing land for multiple uses and for so many different user groups with so many different ideas of what is acceptable or good. Respect does not mean believing everything the BLM, USFS, NRCS or Utah State agencies say and do to be good. I respect plenty of people I disagree with about various topics.

When I first came to Moab Mill Creek Canyon was still sort of a local’s secret. Powerdam area was a mess of fire rings, trash and broken bottles, but most tourists didn’t go there. The immediate Powerdam area aside, it was an entrance to a great hike, as long or as short as you wished – a hidden gem linking Moab to the desert and mountains nearby.

As tourism increased in the early 90s, the BLM began looking at the impacts of higher use at Powerdam and Potato Salad Hill. The road to the waterfall up left hand had already been closed for a while when I came to Moab. The road across the creek from the Powerdam Parking lot to Potato Salad Hill was closed soon after. At the time, the BLM opted to reduce the parking area and work on revegetating the area from the Powerdam to the parking lot. Through all this, local residents kept saying “don’t tell anyone about this place” – don’t mention it at the Moab Information Center, don’t mark it on maps and keep it out of guide books. Since this was before the google, youtube, and facebook it was possible to keep word of Mill Creek somewhat hushed. Not any more.

In the mid 90s group of residents, BLM staff, Utah State School Institutional Trust Lands, Grand and San Juan County representatives, Moab City staff, grazing permitees, local non profits and organizations like the Backcountry Horsemen and some long time seasonal residents came together to make an effort to tackle the increasing use of the canyon and the erosion and damage created by the myriad of new trails people were blazing to get to that perfect secluded spot. The idea was to protect the riparian system, the beauty of the place, and sustain the ability of residents to use the area without creating a whole slew of new rules and regulations.

This group tried hard to work together, and trust was low between participants. We got so bogged down in minutia of how to decide things in a manner that was guaranteed to be representative that we lost a lot of steam and the effort fizzled after a few years. Some good did come of it; some social trailing was reduced; deep gullies forming on often used horse trails were repaired through collaborative efforts between riders and hikers; and a fence was built at the bottom of the Steelbender Trail as it leaves the canyon just upstream of Hidden Valley to reduce off trail thrill riding. During all this I had the privilege of bringing local kids into the canyon to do some of this work – and to build wattles out of Russian olive branches and install them on contour on the slope off the Steelbender Trail that helped catch seed and stop wind erosion, and subsequently regenerated a native plant community there.

In the years since there have been 3 or 4 more iterations of the Mill Creek Partnership, culminating today with the efforts of Sara Melnicoff and the Moab Solutions clean up efforts focused to large degree at the Powerdam and Potato Salad Hill. There is now a pit toilet at the Powerdam parking lot. The interesting thing to me about this repetition of history is that the problems are the same – too many people in one place. However today the scale of the issue is much much greater.

I have also participated as a native plant regeneration specialist in the SE Utah Riparian Partnership here in Moab. I was invited for a time into the Escalante River Watershed Restoration Partnership because of my experience with large scale invasive plant management and native plant regeneration work. I am currently involved with the Colorado Plateau Native Plant Program, a collaboration between various federal land managers, seed producers, restoration practitioners and others. All of these efforts have had their challenges and have been variously effective collaborations focused on land management issues at a broad landscape scale. This is one part of federal and state land ownership that is tedious and sometimes frustrating, but it also can be inspiring and bring positive outcomes to all user groups and the land itself. It illustrates a strength behind public land ownership that is not always present when land is privately owned and private property rights often take precedence over collaboration.

IT’S PUBLIC BECAUSE NO ONE WANTED IT

In the west we have grown and lived with public land since the inception of the states. There is reason for this. At the time of Utah statehood, and even later when land was being given away, much of the west was left unclaimed. Thanks to the Homestead Act of 1862 about 10% of the area of the US was claimed and settled between 1862 and 1976. It was possible through 1976, with a short hiatus from 1934-1946, to acquire up to 320 acres of non-irrigable land in Utah, Colorado, Montana, Nevada, Wyoming, Washington and Arizona for mere dollars per acre, with the caveat that the applicant lived on the land for at least 5 years and grew something there. There were residency rules too. And in arid, rocky areas like those around Moab it was tough to prove your rights and buy the land, unless there was water. The choice places were claimed. It is telling that much of the land was left unclaimed.

According to the Utah State History web page the first commercial oil well in the Moab area was drilled near Thompson in 1911. Apparently oil seemed promising through the 20s, but there weren’t many wells drilled until around 1957. Recently there has been an upswing in drilling in Grand County thanks in large part to advances in drilling technology.

Areas claimed for private ownership in SE Utah, as in most of the West, had access to water. Utah is the 2nd driest state in the Nation. It is no wonder it has some of the smallest amounts of private land.

Uranium was a critical phase in Moab and the surrounding area during the 1950s and 60s. Uranium mining brought prospectors, miners, and all sorts of people to Moab in the early 50s – exploding the population from 1,275 to 4,682 in one decade (according to the 2010 census Moab’s population is now about 5,046). We have an old trailer out back that we use as a storage shed that is a remnant of those boom days when the entire block from 100 N to 200 N and Main to 100 W was a trailer park. The concrete “patios” in our yards are evidence of the chaos of trailers, as is the shower house turned equipment storage behind our house. I have heard stories of the old Moab, and the community mindedness of business at that time. I am not sure Moab is the only place that has lost that sense of care of community in a world full of out of state/country corporations with deep pockets as opposed to mom and pop businesses with a strong connection to place.

Throughout these booms in extractive industries, when public land was still available for nearly nothing just for the asking, the land around Moab was not claimed. No one wanted it then, because there was no way to make a living off of it – even during the uranium boom. Now that extractive practices have evolved, much like the evolution of recreation activities and tools to do them, people want that land. And the problem is, it was decided by people long before us that since no one wanted it that the land belonged to all of us.

UNINTENDED CONSEQUENCES

Faced with the crash of the extractive industries in Moab in the 70s and 80s tourism looked like a great opportunity to help create jobs and an industry for Moab. Locals like Mitch and Mary Williams travelled long distances to create networks with people interested in coming to the desert to tag a long on jeep trips, and the Bill and Robin Groff started Rim Cyclery in 1983. After the last crash, when homes sold in Moab for well under $50,000 for a 3 bed, 1 ½ bath house on ½ an acre ANY industry seemed like a necessary and positive thing. And how bad could tourism be?? A few folks come for a few days, leave some money in Moab and then leave. While it started slowly, as these things do, through word of mouth and small to non-existent budgets for advertising, it built momentum quickly, especially since the dawn of the internet.

As tourism grew Transient Room Taxes (TRTs) were charged to raise funds from the visitors – but due to requirements by the State of Utah a great deal of income is used to advertise Moab and other places in Utah rather than to help fix aging infrastructure like our sewer plant, or make it possible for local EMTs to make a living wage.

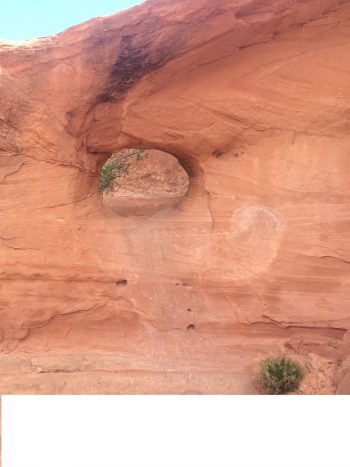

This is a photo of pothole arch — a fairly remote location. Accessible only by foot and mountain bikes. Bikers have chosen to ride through the arch

The unintended consequence of inviting the world here has been the world has come – in large numbers. And with new toys that let them all explore farther and deeper into the desert than I suspect any of the original founders of the tourist industry businesses in Moab could have imagined. In 1964, the same year Canyonlands was designated as a national park, Tag A Long started running jeep trips in Canyonlands and raft trips soon after. At that time you couldn’t buy a raft for personal use – the rigs were army surplus and not cheap, and the rigging and dry bags were also army surplus. Now, not only can you buy a new 16’ Grand Canyon worthy raft for around $5000 (rigged for the trip is another story) for $800 at Sam’s Club you can buy a stand up paddle board. Dry bags, which were manufactured or bought from army surplus, are now available for as little as $15 to 30 at Cabela’s. In the 1980s, after the uranium busted in earnest the Groff brothers started Rim Cyclery. In 1984 they started renting mountain bikes. Like with rafts, specialty bikes for backcountry travel couldn’t be easily purchased like they can be bought today.

People in Moab have always been ingenious when it comes to figuring out how to live and survive in this place. But even I don’t think any of them in the 60s, 70s or 80s had any idea how massive the recreation tourism industry would grow, or how new kinds of off road vehicles and new activities like base jumping and slacklining would dramatically change the face of this town or the lands around it.

Moab and the public lands nearest it is forever changed – and that change started in the 1960s, 70s and 80s.

Around 1994 the Utah State Health Department threatened to shut down camping along the River Road due to elevated fecal coliform levels in the Colorado River due to roadside/riverside camping. Keep in mind this road was only fully paved in the 80s. I remember the days before the pit toilets and developed camp sites. The road was prettier, from afar, but I remember a lot of toilet paper flowers. Like the recently installed light at the junction of Hwy 128 and 191, these changes were essential to accommodate the number of visitors coming at the invitation at first of Moab locals but later by the State of Utah invitations in the form of advertising mandated by the TRT funds. It can be argued that the changes to the public lands brought the people – from where I sit, the people invited to come here forced changes in the public land around Moab in order to ensure it retains some of its integrity.

I come back to the comment “The government is not in the business of taking care of the people or the land, the government is in the business of taking care of the government.” Perhaps the government is a reflection of the governed. Perhaps that is where we need to start.

http://www.rimcyclery.com/history/

http://historytogo.utah.gov/places/moab.html

https://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/2012/winter/homestead.pdf

Kara Dohrenwend is a regular contributor to the Zephyr. She lives in Moab, Utah.

To read the PDF version of this article, click here.

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!